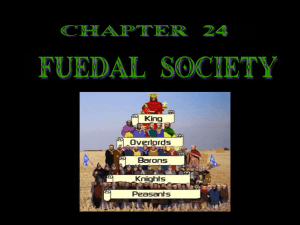

Supported by the brawn and taxes of the peasants, the feudal baron

advertisement

Supported by the brawn and taxes of the peasants, the feudal baron and his wife would seem to have had a comfortable life. In many ways they did, despite the lack of creature comforts and refinements. Around the 12th century, fortified manor dwellings began to give way to stone castles. Some of these, with their great outer walls and courtyard buildings, covered around 15 acres and were built for defensive warfare. Even during the hot summer months, dampness clung to the stone rooms, and the lord and his followers spent as much time as possible outdoors. At dawn, a watchman on top of the lookout tower would blast out a note on his bugle to awaken everyone in the castle. After a small breakfast of bread and wine or beer, the nobles attended mass in the chapel at the castle. The lord then went about his business. He first may have listened to the report of an estate manager (a manager of plot of land). If an unhappy or badly treated serf fled, the lord would order special people called retainers to bring him back. This is because serfs were bound to the lord unless they were able to escape from him for a year plus a day. The lord might also hear about the petty offenses of the peasants and fine them or sentence them to a day in the pillory. Serious deeds, like poaching or murder, were legal matters for the local court or royal "circuit" court. The lady of the castle had many duties of her own. She inspected the work of her large staff of servants, and saw that her spinners, weavers, and embroiders furnished clothes for the castle and rich robes for the clergy. She and her ladies also helped to train the pages - well-born boys that came to live in the castle at the age of seven. For seven years, pages were taught religion, music, dancing, riding, hunting, and some reading, writing, and arithmetic. When they turned 14, they became squires. At the age of 21, if they were worthy enough, they received the distinction of knighthood. Sometime between 9 AM and noon, a trumpet called the lord's household to the great hall for dinner. There, they wolfed down great quantities of soup, game, birds, mutton, pork, some beef, and often venison or boar slain in the hunt. In winter, the ill-preserved meat tasted fiercely of East Indian spices bought at enormous cost to hide the rank taste. Coffee and tea were not used in Europe until after the Middle Ages. Minstrels or jokers entertained at dinner. Hunting, games, and tournaments delighted nobles. Even the ladies and their pages rode into the field to release falcons at game birds. Indoors, in front of the great open fire, there was chess, checkers, and backgammon. Poet-musicians called troubadours, would often chant and sing storied accomplishments of Charlemagne, Count Roland, or Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Tournaments were of great value as practice for feudal warfare. At least one battle or raid occurred daily because medieval nobles settled their quarrels by attacking. If a lord coveted land belonging to someone else, his couriers ordered his vassals to make a raid for it. The peasants, in quilted battle coats, trudged along to fight with their pikes and poleaxes. Despite the numerous outbreaks, casualties were surprisingly few because long battles rarely occurred. Warring lords usually just burned the fields and villages of their enemies. After an encounter, the defending lord and his vassals would flee to the safety of the castle.