Five Step Approach To A Text

advertisement

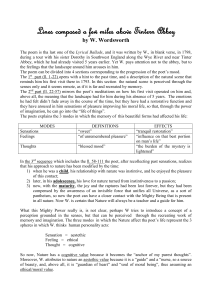

Five Step Approach To A Text 1. Denotation and Connotation: We begin by determining the denotative (dictionary) meaning of all the words in the text. Because poems are generally short, the poet chooses his/her words carefully – often not to limit meaning but to expand it. Words whose denotation is not known or is not clear: LOOK THESE WORDS UP! Once we have assured ourselves of the denotation of all problematic words, then we can proceed to their connotative meanings. Some words, such as symbolic words, like “rose”, have meanings that extend beyond their denotation. We call these “meanings” their connotation. Examine the title “Sailing to Byzantium”. Is Byzantium a “real” place, or is it largely a place of the mind? If that is the case, what does sailing to it connote? 2. Movement: Movement in a poem refers to what is literally happening. If the poem is a narrative, what is the story? If the poem is comparing or contrasting two things (like in a metaphor) what are the two things being compared or contrasted? And so on…. In Yeats’ poem there appears to be several movements, but one overall movement that encompasses all the stanzas. We begin identifying what each stanza does (not means) and then we look at the overall structure and make a determination of what the poem as a whole does. Unlike meaning where there are various interpretations possible, movement is generally assessed uniformly – that is, all readers come to the same conclusions. 3. Units of Meaning: You have already begun with words, the smallest unit of meaning. Now you examine these same words to determine the register and voice. Secondly we look for phrases and sentences and their arrangement. Here we have elements such as caesura, line breaks, enjambment that arrange words in a particular fashion with the intent of manipulating the reader into reading the words the way the poet had intended. Finally, we look at stanza formation, paragraphing, or, in the case of concrete poetry, at the graphic layout. Do we see any significance in any of these structures? Why, for example, would a poet have chosen a sonnet form and not a villanelle form for his/her subject? Why is there a line break after a verb, and not after a preposition? 4. Repetition: By now we should have a clear picture of the poem’s diction and action and we begin to notice repeated images, words, phrases, ideas, rhyme, meter, etc. If the poet uses multiple expressions that refer to age or ageing then perhaps this idea is a significant one. If he/se repeats the same rhyme, or if he/she has a consistent meter for five lines, and then breaks that meter in the sixth line, we ask why? Sometimes it means nothing, sometimes it means, “look at me”, and sometimes it just means that the poet has not really mastered his/her craft. We always assume that the writer does something for a purpose, because we have no other choice. Not making a choice is still a choice. It is helpful to track these changes to help us find a pattern. Personally, I use a pencil to map a text, which means that no one will ever want to buy one of my books. I am also a big believer in marginalia! 5. Author/Narrator’s Attitude Towards the Subject By this time we should begin to detect an attitude. The diction (word choice), the metaphors, the phrases, etc all begin to point in a direction. The poet may be nostalgic, angry, sarcastic, etc. It is necessary to remind us that the author is not necessarily the narrator, even if the poem is written in the first person.