Natural Hazards Mitigation - R.D. Flanagan & Associates

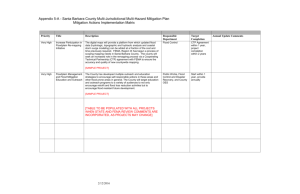

advertisement