AQA A2 Sociology Unit 4 WORKBOOK ANSWERS

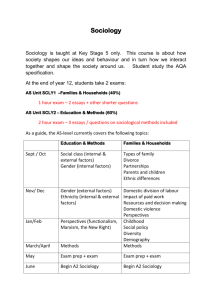

advertisement