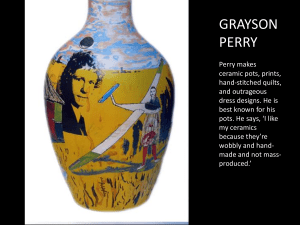

Perry_box.revised

advertisement

Coalitionary aggression in white-faced capuchins. Susan Perry, UCLA Until quite recently, little was known about the dynamics of social relationships in New World monkeys, and the vast majority of research on social complexity in primates was conducted on Old World monkeys and apes. Because of their extraordinarily large encephalization quotients (which can be calculated from data in Harvey et al. 1987), proponents of the social intelligence hypothesis would certainly expect to find social complexity and cooperation in the gregarious capuchin monkey, genus Cebus. Indeed, capuchins, unlike most other New World monkeys, form frequent coalitions in a wide variety of contexts, and it seems reasonable to assume that skill in forming and maintaining alliances is critical for enhancing reproductive success. Here, I present data from a wild population of white-faced capuchins, Cebus capucinus, studied at Lomas Barbudal Biological Reserve, Costa Rica from 1990-2001. Capuchins have an elaborate repertoire of gestures for coalitionary aggression (see accompanying photo of the “overlord,” the most frequent coalitionary posture). They form coalitions in a broad array of social contexts. About 25% of female-female coalitions vs. conspecifics occur in the context of feeding competition (Perry 1995). Even when the monkeys are foraging in trees large enough to hold the entire group plus a few more individuals, the lowest-ranking male and female are typically barred from entering the tree by coalitions. Redirected aggression towards subordinates is common in capuchins, and many coalitions occur in the wake of other fights or in other socially tense situations. Rank reversals always entail extensive coalitionary involvement from multiple individuals. Although the female dominance hierarchy is relatively stable and linear, changes occur when adolescent females ascend the hierarchy, and when key members of social networks die, leaving their former allies vulnerable to being challenged (Perry 1996a, Manson et al. 1999). Unlike most Old World monkeys with despotic ranking systems, capuchin females do not appear to support their own daughters preferentially in the rank acquisition process (Manson et al. 1999). All adult males are dominant to adult females in most capuchin groups (Fedigan 1993, Perry 1997). The alpha male has a very distinct role from subordinate males, but the relative rankings of subordinate males are sometimes difficult to discern (Perry 1998a). Both of the two overthrows of the alpha male that were witnessed at Lomas Barbudal were bloody and involved large coalitions of both males and females. The alpha male was killed in one of these reversals (GrosLouis, in prep), and in the other the alpha male was temporarily evicted but returned as a subordinate male later (Perry 1998b). One coalitionary context particularly noteworthy because of its parallel with chimpanzee coalitionary strategies (de Waal 1978; Nishida and Hosaka 1996) is separating interventions. Separating interventions are quite common in capuchins, and although they are employed by both males and females, they are a particularly common strategy used by alpha males (Perry 1998a,b). When the alpha male sees two subordinate males affiliating or engaging in a sexual interaction, he threatens one of the two and solicits aid from the other one, thus ending the interaction. The alpha male is remarkably inconsistent with regard to which males he supports against which other males, even over short time intervals, and this coalitionary fickleness, combined with the fact that the alpha male rarely permits subordinates to associate, may account for the lack of clarity in subordinate males’ dominance relationships (Perry 1998a,b). According to the standard definition of coalitions (de Waal and Harcourt 1992:3), a coalition involves aggressive cooperation between group-mates against conspecifics. However, capuchins engage in the same motor patterns as found in true coalitions when they cooperate in menacing heterospecifics, and these pseudocoalitions are far more common than true coalitions. For example, 25% of all male-male coalitions are directed at monkeys, and the rest are directed at heterospecifics, including both predators and harmless creatures (see below). Although all group members mob predators to to some extent, adult males are the most frequent participants (Perry 1995, Rose 1998). When adult females form coalitions with adult males against potential predators, they do so preferentially with the alpha male (Perry 1997). Capuchins form pseudocoalitions against harmless animals such as frogs, deer, anteaters, howlers & primatologists, and sometimes even inanimate objects. For example, capuchins sometimes form vehement and prolonged coalitions directed at a pile of monkey feces, some innocuous-looking insect, a dead or sleeping animal, an egg, or a bare patch of dirt. In fact, these pseudocoalitions are far more common than coalitions against conspecifics. Pseudocoalitions most likely serve to communicate something about the relationship between the two participants. It is possible that they provide practice in coordinating aggression for future coalitions against other monkeys and predators. Because pseudocoalitions are often prolonged and can consume a fairly significant portion of the activity budget, the opportunity costs entailed by engaging in them may also make them useful signals of commitment to alliances. One of the most common contexts of pseudocoalitions is when a subordinate monkey is foraging peacefully and a dominant comes into view, heading his way. Then the subordinate will start threatening the harmless target and solicit aid from the dominant, who almost invariably responds by joining in the threats and perhaps forming an overlord. Psuedocoalitions may be an effective tactic for subordinates to avoid displacements by dominants at feeding sites, as the dominant often leaves the subordinate to feed peacefully following a pseudocoalition. The last main context of cooperation is male-male coalitions vs. extragroup males (Perry 1996b). During intergroup encounters, the females and juveniles flee while the resident males of each group form coalitions with one another against the males of the other group. Intergroup fighting sometimes results in severe wounding and is probably very important in preventing foreign males from immigrating. Immigration of a group of males generally results in the eviction of some or all of the resident males, and there are sometimes infanticides associated with turnovers in male membership (Fedigan et al. 1996, unpublished data, Rose 1998). Two infanticides have been witnessed at Lomas Barbudal (Julie Gros-Louis, pers. comm.), and several infanticides have also been reported at the nearby Santa Rosa (Rose 1994, K. MacKinnon & K. Jack pers. comm.). Partner choice in coalition formation follows a set of fairly rigid rules in capuchins. When a monkey witnesses a fight between a female and a male and opts to take sides, s/he sides with the female 85% of the time, despite the fact that males are dominant to females. In the fights that did not conform to this pattern, the victim was a low-ranking female and the male’s supporter was a female higher-ranking than the victim. When fights break out between same-sexed partners, however, capuchins almost always support the dominant opponent. This is true in about 89% of male-male fights, and 98% of female-female fights, and most exceptions to this rule consist of an adult supporting a juvenile against an adult. Capuchins also tend to preferentially support monkeys with whom they have more affiliative relationships (as measured by “proportion of interactions that are affiliative”); in 85% of those fights in which a witness chose to join in the fight, s/he supported the monkey with which s/he had the more affiliative relationship. All three of these “rules” (preference for females, dominants, and affiliative partners) exert independent effects on partner choice. Capuchins clearly have complex social relationships and social organizations, and their coalitionary strategies parallel those of chimpanzees in many ways. The extent to which cognitive complexity is involved in creating the observed patterns of behavior is less clear, and further research in captive settings will probably be necessary to resolve this issue. References: de Waal, F.B.M. (1978) Exploitative and familiarity-dependent support strategies in a colony of semi-free living chimpanzees. Behaviour 66:268-312. de Waal, F.B.M and Harcourt, A.H. (1992) Coalitions and alliances: a history of ethological research. In Coalitions and Alliances in Humans and Other Animals, A.H. Harcourt and F.B.M. de Waal (eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Preses. pp. 1-19. Fedigan, L. M. 1993. Sex differences and intersexual relations in adult white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Int. J. Primatol. 14: 853-877. Fedigan, L.M., Rose, L.M., and Avila, R.M. 1996. See how they grow: tracking capuchin monkey populations in a regenerating Costa Rican dry forest. In Adaptive Radiations of Neotropical Primates, M. Norconck, A. Rosenberger and P. Garber (eds.). New York: Plenum Press. pp. 289-307. Harvey, P., Martin, R.D., and Clutton-Brock, T.H. 1987. Life histories in comparative perspective. In: Primate Societies. (B.B. Smuts, D.L. Cheney, R.M. Seyfarth, R.W. Wrangham, and T.T. Struhsaker, eds.), Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 181-19 Manson, J.H., Rose, L.M., Perry, S. and Gros-Louis, J. 1999. Dynamics of female-female relationships in wild Cebus capucinus: Data from two Costa Rican sites. Int. J. Primatol. 20: 679-706. Nishida, T. & Hosaka, K. (1996). Coalition strategies among adult male chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. In: Great Ape Societies. W. C. McGrew, L. F. Marchant & T. Nishida (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 114-134. Perry, S. 1995. Social Relationships in Wild White-faced Capuchin Monkeys, Cebus capucinus. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. Perry, S. 1996a. Female-female relationships in wild white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Int. J. Primatol. 40: 167-182. Perry, S. 1996b. Intergroup encounters in wild white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Am. J. Primatol. 17:309-330. Perry, S. 1997. Male-female social relationships in wild white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus) Behaviour. 134: 477-510. Perry, S. 1998a. Male-male relationships in wild white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Behaviour 135: 139-172. Perry, S. 1998b. A case report of a male rank reversal in a group of wild white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). Primates 39: 51-69. Rose, L.M. 1998. Behavioral ecology of white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus) in Costa Rica. Ph. dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis. Rose, L.M. 1994. Benefits and costs of resident males to females in white-faced capuchins, Cebus capucinus. Am. J. Primatol. 32:235-248.