NGfL – GCSE Religious Studies – Christian Philosophy and Ethics

advertisement

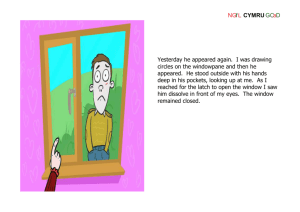

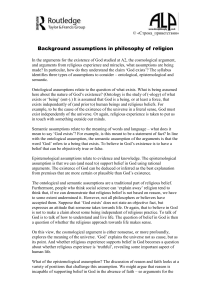

NGf L CYMRU GCaD GCSE Religious Studies Unit 5 - Christian Philosophy and Ethics Beliefs, Teachings and Sources: The Existence of God Teaching Notes The following resources are intended to support classroom delivery and/or independent study. So, the teacher may use them as a teaching aid or the student may work through them at his or her own pace. They may also be used for small group work. I've tried to design the materials so that they fit as wide as possible a range of delivery. However, they will work best through the use of an interactive whiteboard in a classroom situation. The materials are intended to support the 'Existence of God' element within the 'Beliefs, Teachings and Sources' section of Unit 5 of the GCSE Religious Studies syllabus, Specification A (Christian Philosophy and Ethics). The topics covered are: 1. 2. 3. 4. Why some people have religious belief whilst others do not. The argument from design for the existence of God. Secular approaches. Reason and revelation as approaches to philosophical discussion about God's existence. In covering these topics it seemed more coherent to cover (4) before (3), so I've swapped them around. However, the teacher can use them in any order or as stand-alone resources if used carefully. To aid in delivery I supply below some brief notes as to what the activities in each resource were intended to achieve. Unit 1: Believing and Doubting Reasons for Belief/Unbelief. The list here is not exhaustive, and the teacher should be open to suggestions that do not fit neatly into any of the categories. It should be noted, however, that the two lists (belief/unbelief) are parallel: e.g. tradition may perform positive or negative role, as can personal experience, etc. Atheist, Theist, Agnostic. It's important to emphasise here that 'atheist' should not strictly be applied to polytheists, Buddhists, etc – though it sometimes is. This in itself is an interesting discussion point. It should also be stressed that agnostic is not a final position, but rather an openness or even an expression of a lack of interest. The difference between ‘religion’ and ‘philosophy of life’ is an interesting discussion point. For instance, can there be a secular religion? A. C. Grayling’s ‘atheist bible’ is another interesting jumping off point for discussion. Unit 2: Arguments for the existence of God Subjectivity and Objectivity. This can be a complicated and tricky topic. Higher ability students may spot that, for instance, 'subjective' can have two meanings: something that is a matter of opinion or personal preference (I like cheese), but also something that is experienced by a subject. Therefore, some subjective things may be considered matters of fact because we all have the same personal reaction (e.g. salt is bitter, sugar is sweet). So, subjective does not necessarily imply NGf L CYMRU GCaD something that is merely a matter of personal taste. However, this is probably too subtle a point to bring out at GCSE, and the main purpose of the exercise is merely to contrast personal opinion or preference (I like cheese) with objective and measurable fact (Paris is the capital of France, 2 + 2 = 4). Objective proof for God would resemble the latter form, and the arguments for the existence for God would be objective in the sense that they are logically undeniable (if they were true!). Arguments for the Existence of God. Firstly, the drag and drop exercise here (match the terms to the arguments) is not testing student knowledge, but a means of involving them (they’ll have to guess to get the right answers, probably – though there are some clues.) Regarding the general approach to the arguments themselves, the point here is that the various arguments mentioned – cosmological, ontological, moral, teleological – are all at least controversial. In this sense, they may be said to fail to convince everybody. Obviously, there are still people who hold them, in some form, but the fact that they are disputed suggests perhaps that God's existence may not be decided by reason alone. The extended discussion and criticisms of the design argument in this unit is meant to illustrate this. The design Argument. In the two exercises concerning which features apply to man-made objects, and which to natural ones, the point is to show that the watch analogy is not a perfect fit (revealing a weakness of the argument). Whilst there are 'right' answers in the word list, there is obviously some ambiguity about certain phrases. For instance, a student might argue that a stone may be 'complex' (in a sense – formed by complex processes), or that a tree or a human heart has a natural purpose (to regulate the carbon dioxide in the air; to pump blood). These responses are not wrong, and if the teacher wishes they can be used to generate discussion – can we have natural 'purpose' without a designer? Some philosophers/biologists think so, others don't. Hume's 3rd Criticism. The point of this exercise is to show how difficult it is to argue conclusively from an effect back to its cause – from a watch, for example, back to the watchmaker. To do this, the teacher could select some objects about which only he or she knew the personal history, and get the students to guess the nature of the designer(s); or, the students themselves could imagine or select objects. The point is simply to show how hard this is to get this right (and how it reveals a weakness of the design argument). Unit 3: Secular Approaches Secularism and Humanism. As described, secularism isn't the same as atheism (though they are often taken together). Someone like John Locke, for example, was religious, but held that secular government is the best form for reasons of individual freedom and social stability. The same goes for humanism, which may be atheistic (e.g. the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre) or religious (e.g. the philosophy of Erasmus or Montaigne). These distinctions may be too subtle for some GCSE students, and potentially confusing, so need to be handled carefully. Evolution. The outline of evolutionary theory is meant to give the student a more thorough basis for evaluating the three alternative approaches outlined later: creationism, atheism, or theistic evolution. The point is to show that evolution is a well-supported and detailed theory which cannot easily be rejected. This prepares the ground for the discussion of the nature of religious belief in the following and final unit, where the student is presented with alternatives to the literal interpretation of scripture. Care should also be taken to distinguish theistic evolution from so-called intelligent design, the former being a broader and less scripturally bound perspective, the latter being closer to creationism. NGf L CYMRU GCaD Unit 4: Reason vs Revelation Proof. The purpose here is to underline the fact that our everyday 'certainties' are far from absolutely certain, and that much must be taken on trust. Concerning religious belief, therefore, we might argue that evidence (or the lack of it) is not perhaps as critical as some think. The brief discussion of Descartes is meant to illustrate that even philosophy and science cannot absolutely justify our common view of the world. The Proof/Faith Continuum. The continuum shows how, historically, philosophers and theologians have differed in their view of what religious faith is. The teacher might like to follow up one of two of the examples cited – Pascal's wager would be a good one that would be accessible to most students. Metaphorical/Symbol and Literal. These are quite loose and general terms, but the main point is simply to underline that language isn't always literal. The teacher might consider here not only metaphors and idioms, but parables and stories, and other forms of symbolic representation and truth (e.g. the 'truth' of a fairy tale or work of fiction). Also, if the teacher wanted to go into more detail then he or she could discuss (for instance) Aquinas' account of the different ways in which religious language can be interpreted.