tackling - Iowa State University

advertisement

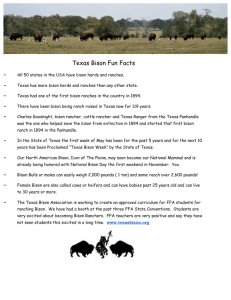

Rocky Mountain News, CO 07-06-06 Tackling 10,000-year-old mystery Students take fresh look at what killed herd of 600 bison Larry Agenbroad © Special to the News Ten thousand years ago, a band of nomadic hunters stampeded 600 bison off the edge of a small cliff then speared and butchered the beasts before hauling off the meat. Or maybe not. Maybe, instead, a lightning bolt or a swift-moving grass fire killed the whole herd, and their remains were quickly buried beneath wind-blown sand and silt. A few decades later, hunters camped on the buried bison remains, leaving behind stone spear points and tools that, over the millennia, have mixed with the animal bones. Those conflicting interpretations confronted University of Colorado archaeology students last month at the Hudson-Meng Bison Kill on the Oglala National Grassland, about 330 miles northeast of Denver. Students in the CU archaeology summer field school were at ground zero in the rancorous, protracted debate over who or what killed the Hudson-Meng bison. The bones were discovered in 1954, and the dispute still rages. For the CU undergraduates, the dig provided a rare glimpse beyond the blackand-white of textbook narratives, into the often-murkier realm of real-world science. "In the classroom, things are presented as 'This is how it happened,' " said Kirsten Smith, a junior anthropology major. "But out here we see the process in action, the process of gathering information to support different interpretations," Smith said. Archaeologist Mark Muniz, who supervised CU students digging two exploratory trenches near the southern edge of the bone layer, called the Hudson-Meng dispute "a major controversy among archaeologists that has received very little press." 'Kill' added to site name How hot is this topic? The original 1970s excavator of the site, Larry Agenbroad, took over management of Hudson-Meng from the U.S. Forest Service in May. A vocal defender of the stampede-'em- and-spear-'em interpretation, he renamed the site to include the words "Bison Kill" and removed five interpretive signs presenting the opposing theory. "I'm going to set the record straight," said Agenbroad, a professor emeritus at Northern Arizona University who also operates The Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, S.D., a research and tourism facility. Agenbroad made headlines a few years ago by suggesting the possibility of cloning extinct woolly mammoths using DNA extracted from carcasses preserved in Siberian permafrost. "This site deserves the best research possible, and I don't think it's had it in the last decade," he said of Hudson-Meng. "They made some sweeping statements to fit preconceived ideas." On the other side of the debate are Colorado State University archaeologist Lawrence Todd and Iowa State University archaeologist David Rapson. "I'm not surprised," Rapson said when told that Agenbroad had removed interpretive signs from the Hudson-Meng visitor center. "He's very strongly committed to his position and is making a substantial investment to interpret the site the way he wants it interpreted," Rapson said. "But we always tried to present both sides, rather than just giving visitors one interpretation and then saying, 'Thank you very much. The gift shop is over here.' " Spear point found early on A bulldozer uncovered the Hudson-Meng bones in 1954. In October 1971, Agenbroad, then at nearby Chadron State College, led the first formal excavation of the site. Around 9 a.m. on the first day of the dig, a 6-inch stone spear point was found protruding from beneath bison ribs in one of the trenches. It was made of beer-bottle-brown flint, and its distinctive tapered shape defined it as an Alberta Culture spear point. Alberta Culture big-game hunters roamed from the Canadian prairie provinces to northern Colorado about 10,000 years ago. Twenty-one other partial or whole Alberta points have been found at the bisonbone site, along with stone butchering tools and more than 3,500 small stone "waste flakes" produced during the tool-making process. Radiocarbon dating showed that the bison bones are about 10,000 years old. Agenbroad concluded that Alberta Culture hunters stampeded the bison off a small cliff then finished them off with spears. The site became known as the Hudson-Meng Bison Kill, named for two Crawford-area men - Albert Meng and Bill Hudson - who first suggested that early hunters might have killed the bison. The name stuck until 1991, when the U.S. Forest Service funded new research at the site by Todd and Rapson. The new team concluded that most of the spear points and other stone tools had been recovered about two inches above the main bone layer. They soon became convinced that Hudson-Meng held the story of two distinct, unrelated events: the sudden death of hundreds of bison, followed a few decades later by the arrival of Alberta Culture hunters who occupied the site and left behind spear points and tools. Nature's role considered Repeated freeze-thaw cycles, erosion and other natural processes may have allowed the artifacts to work their way down into the main bone layer, Rapson said in an interview. Todd and Rapson convinced the Forest Service to rename the site the HudsonMeng Bison Bonebed, a label that describes the remains without speculating about how they got there. The new name lasted until Agenbroad took over in May. Now every T-shirt, coffee mug, refrigerator magnet, baseball cap and necklace in the gift shop is stamped "Hudson-Meng Bison Kill." When you see Agenbroad's photographs of spear points under, beside and protruding from bison bones, it's hard to believe that natural processes placed them there. And in fact, Rapson and Todd concede that hunters slayed a few bison at the site. But they contend that the killings occurred decades after the initial mass death; later, some of the spear points and bones worked their way down into the main bone pile, Rapson said. While rejecting Agenbroad's interpretation, Rapson admits that he and Todd can't say with any confidence what killed the bison. Among the possibilities: The herd was standing in a stream when lightning struck, zapping all the shaggy ruminants. Or, a raging grass fire sucked the oxygen from the air and asphyxiated them. But there's no physical evidence to support the lightning or asphyxiation ideas. "We're in kind of a funny situation here," Rapson said. "We feel our research has brought into question the original interpretation. But if it's a natural mortality, we're unable to provide a strong interpretive answer for what did happen. "This dispute will go on for years and will be seriously, acrimoniously debated," he said. What's at stake? The outcome could alter archaeologists' views about the capabilities of early Paleoindian hunters, who roamed the Americas more than 6,000 years ago. "Hudson-Meng has been a very curious outlier from the main pattern of Paleoindian behavior," Rapson said. "This has always been considered the earliest example of a bison jump site with a huge number of animals killed." Jump site could be unique Most of the oldest North American bison "jumps," places where ancient hunters drove herds over cliffs to kill them, date to 4,000 or 5,000 years ago, he said. If Agenbroad is right, then the 10,000-year-old Hudson-Meng site represents an "anomalous and unique" find, he said. Agenbroad disagreed. He said there's an equally old bison jump site in Texas. "These people are not given credit by some archaeologists for being as skilled and knowledgeable as they were," he said of the Alberta hunters. "They knew what they were doing, and they did it efficiently." For CU archaeologists and their students, this summer's excavation provided an opportunity to find new evidence that could help - maybe, someday - resolve the issue. "The fact that there's a controversy raises the stakes of what we're doing here," CU student Smith said. "It makes the need for accuracy that much more important." "Here, the starting point is, is this a kill or not?" said CU archaeologist Doug Bamforth, director of the archaeology field school. "The idea that you can have a place and not know what it is - that's sort of a cool thing," he said. "It makes you think much harder about what you're doing, if you can't even answer that basic a question about what you're looking at." The bison bones cover an area a bit smaller than a football field and are enclosed in a climate-controlled steel building. A portion of the original 1970s excavation has been reopened for tourists to view. At two trenches dug a few feet south of the building, Muniz and his student workers believe they've found evidence for two ancient surface-soil layers directly above the main bone pile. Both of the ancient surface layers contain bits of charcoal and broken bone, along with tiny stone flakes produced during prehistoric toolmaking. If Muniz is correct, the former surface layers may have held artifacts that gradually worked their way down to the 10,000-year-old bones. It's a finding that could lend support to the Todd-Rapson theory. But Muniz was quick to add that the Hudson-Meng puzzle won't be solved any time soon. "The work we do here - I don't know if it will settle any of the controversy at all," he said. "We're just refining the data and seeing it a bit more clearly."