Appendix D - PSHE Education in Schools

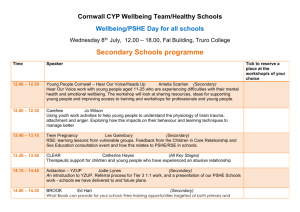

advertisement

PERSONAL, SOCIAL, HEALTH AND ECONOMIC EDUCATION IN SCHOOLS A Summary of the Ofsted Report – Ref No: 090222, July 2010 DSS 10/11 01 1. INTRODUCTION Personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education has now been part of the National Curriculum for over 10 years, and is intended to support pupils’ learning and personal development. The report draws evidence from inspections of PSHE education between September 2006 and July 2009 in 92 primary and 73 secondary schools in England. Much of the evidence comes from direct observations of PSHE lessons or of lessons that the schools described as having PSHE content. It also draws on evidence from visits related to business and economic education during the same period. Discussions with teachers, school nurses and parents and observations of activities related to PSHE, such as assemblies and clubs, also contributed to the evidence.1 2. KEY FINDINGS Overall provision for PSHE education was judged to be good or outstanding in over three quarters of the schools visited and at least satisfactory in all but one of the schools surveyed. Pupils’ personal development was good in most of the schools visited and was outstanding in about a third of the schools. Pupils had positive attitudes towards PSHE education. Pupils had good knowledge and understanding of healthy eating and the importance of exercise, although they did not always put this knowledge into practice in the choices they made. PSHE teaching was good or outstanding in over three quarters of the schools visited, characterised by good relationships and effective classroom management. The more effective schools used a range of external agencies to engage pupils successfully and enliven lessons. Elsewhere, the quality of teaching was often too variable and, in about a quarter of the lessons seen, teachers had insufficient subject knowledge and expertise. The result was lessons that were dull and sometimes superficial. The use of external presenters was poorly planned and less effective and did not link well with classroom activities. Most of the schools visited provided a wide range of extra-curricular activities where pupils could apply and develop their PSHE learning. The many peer mentoring schemes which had been introduced, where students were trained to support one another, were particularly effective. Lack of discrete curriculum time in a quarter of the schools visited, particularly the secondary schools, meant that programmes of study were not covered in full. The areas that suffered included aspects of sex and relationships education; education about drugs, including alcohol; and mental health issues that were not covered at all or were dealt with superficially. Effective PSHE education was supported by the National Healthy School programme, the national programme for continuing professional development in PSHE and the social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) initiative.2 In the schools visited, parents were rarely involved with or consulted about PSHE education, although there were some examples of outstanding practice involving parents. The assessment and tracking of pupils’ progress in PSHE education were inadequate in 15 of the 73 secondary schools visited. The assessment of PSHE was ineffective in important respects in about half of the primary and secondary schools, although elements of it were in place. Nearly all the secondary schools visited in the final two years of the survey were aware of the new programme of study for economic well-being and financial capability. However, the early evidence from the survey suggested continuing issues of concern in this area, with the provision for financial capability weaker than that for enterprise or careers education. 1 Healthy schools, healthy children? The contribution of education to pupils' health and well-being (HMI 2563), Ofsted, 2006; www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/2563. [See DSS summary: DSS 06/07 5] Developing financially capable young people (070029), Ofsted, 2008; www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/070029a. [See DSS summary: DSS 07/08 39] 2 The Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) programme is a resource for primary schools to develop pupils’ social, emotional and behavioural skills. For further information, see: http://nationalstrategies.standards.dcsf.gov.uk/primary/publications/banda/seal. 1 3. RECOMMENDATIONS The Department for Education, with its delivery partners, should: support work to ensure that all trainee teachers understand the role of PSHE education in the National Curriculum, develop routes for initial teacher education in PSHE education, and promote the take-up of continuing professional development in PSHE education; with other government departments, such as the Department of Health, support schools to implement systematically the revised guidance on sex and relationships education and drugs education; support the development of good practice in assessing PSHE education, and publicise this widely to schools. Local authorities should: consider how they can support schools most effectively in developing PSHE education programmes by providing access to high-quality continuing professional development; facilitate networks of teachers to develop PSHE knowledge and skills and, in particular, encourage the involvement of schools where the provision is weak. Schools should: ensure that the timetable is organised so PSHE education is coherent, comprehensive and of high quality; meet the needs of pupils for timely and appropriate teaching about high-risk areas such as sex and relationships, drugs and mental health issues; focus on pedagogy to make lessons active, compelling and relevant, and ensure that teachers have the specialist knowledge, training and skills they need to teach PSHE education successfully; implement systems for assessing and tracking pupils’ progress in PSHE education; involve and consult parents more in developing and implementing the PSHE curriculum, so they are aware of the topics being covered. The full report can be viewed/downloaded at: http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/publications/090222 © Document Summary Service 2010. University of Bristol Graduate School of Education, 35 Berkeley Square, Bristol, BS8 1JA. 2