Text type, genre, register and style (Vestnik, 2004)

advertisement

TEXT TYPE, GENRE, REGISTER AND STYLE IN RELATION TO TEXT

ANALYSIS AND TRANSLATION

Introduction

Although the terms text type, genre, register and, to a lesser extent, style are widely used in both

linguistics and Translation Studies, there seems to be little general consensus with regard to their

meaning. The aim of the present paper is to discuss varying definitions of these terms and to suggest

how they can be used to describe situational variation among texts. Our survey includes an overview

of the disciplines of register studies and genre analysis, as well as efforts within Translation Studies

to define text type. The discussion should be of relevance not only to those concerned with

translation, but also to all those interested in the analysis of non-literary texts.

Style

Style has been defined in a broad range of ways over the years and has become a kind of umbrella

term for a range of factors both textual and contextual. Generally, style is seen as concerned with

choices made by individual writers, judged in relation to norms. The situational dimensions

governing stylistic choices may be relatively permanent – for example, to do with dialect or time –

or relatively temporary and/or localised. The latter relate to the professional or occupational activity

involved, the status or relative social standing of the participants in the communication situation, the

specific purpose of the communication, and the idiosyncratic preferences of the individual writer or

speaker (cf. Crystal and Davy 1969). The other factors influencing stylistic choice are the

fundamental features of language use – in particular, the medium involved and whether we are

concerned with monologue or dialogue. Deviations from norms may be qualitative, i.e. a breach of

a rule or convention, or quantitative, i.e. in terms of frequency of occurrence of particular features

or items. However, norms are flexible (Leech and Short 1981) and may be creatively extended –

which, of course, is the most difficult stylistic feature for a translator to deal with.

By contrast, register is concerned with group convention and in relation to many kinds of functional

texts, individual writers and their choices do not have the same status: the more specialized the text,

the more concerned we are with register rather than style and the more likely it is that writers will

not even be named. Thus, to a large extent, style studies has been replaced by register studies,

especially in relation to non-literary texts (cf. Hatim 1997: 13ff and Snell-Hornby 1988: 120ff).

Register

The most influential discussion of register is still that found in the study of cohesion by Halliday and

Hasan (1976), who introduce the concept in order to deal with textual meaning. The register is “the

set of meanings, the configuration of semantic patterns, that are typically drawn upon under the

specified conditions, as well as the words and structures that are used in the realization of these

meanings” (Halliday and Hasan op.cit. 23). Register has three elements: field, which covers subject

matter, the purposive activity of the speaker/writer and the nature of the social action that is taking

place (basically, 'what is happening?'); tenor, which covers the relevant role structure or social

relations, both permanent and temporary ('who is involved?'); and mode,1 or symbolic organization

1

There is also 'rhetorical mode', which is what the text is achieving in terms of narration, description, exposition and

argument; these are referred to by rhetoricians as 'modes of discourse' but also (e.g. Faigley and Meyer 1983) as 'text

types', which is how they are frequently discussed within Translation Studies (see below).

1

of the text and its function in the context, including the channel, which can be described as the axis

spoken-written ('what part is language playing?').

This tripartite model fits neatly with the three sets of underlying options, strands of meaning

potential, or macro-functions identified by Halliday (1970), to which the options in the grammar of a

language are related and which can be combined in any utterance, as required. The ideational

function is concerned with cognitive meaning (related to our experience of the world, both internal

and external) as well as with basic logical relations; in serving this function, language "gives

structure to experience, and helps to determine our way of looking at things" (Halliday op.cit. 143).

The interpersonal function relates to uses of the language to express social and personal relations,

or the varying roles that we adopt in communication situations. These roles are defined by language

itself: every language offers options whereby the user can vary his or her own communication role,

making assertions, questioning, giving orders, expressing doubts and so on; these basic speech

functions are expressed grammatically by the system of mood and differ when the role adopted by

the language producer differs. Finally, the textual function enables us to construct texts or

"connected passages of discourse that is socially relevant" (ibid.); and for Halliday it is the text,

rather than the word or the sentence, that is the basic unit of language. These discussions of different

language functions which can be realised simultaneously provide an alternative to the assumption

that language use, particularly in written text, is concerned only with the communication of

information. The organization of a written text indicates how it is to be read, but there is much more

involved than the distribution of factual or propositional information – language is multi-functional.

Thus field corresponds with ideational meanings, which are realised in the choices made within

linguistic systems such as transitivity; tenor with interpersonal meanings, which find expression in

the mood and modality of text; and mode with textual meanings, reflected in factors such as ThemeRheme progression or distribution of given-new information.

To hang together, texts need to display consistency of register: coherence of meaning is dependent

not only on content, but on selection from the semantic resources of the language. A text is

“coherent with respect to the context of situation, and therefore consistent in register; and it is

coherent with respect to itself, and therefore cohesive” (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 23, my emphasis).

However, cohesion is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the creation of text and the

relation of text to the context of situation is very variable. As it is hard to draw a line between the

same and different situations, we cannot ask whether texts are in the same register, we can only ask

in what respects they differ or are alike. In comparing texts, subject matter is no more or less

important than other factors – indeed, the idea of a single register corresponding to any one situation

is a myth (cf. Hatim 1997: 22ff). A text needs continuity of register – the pattern formed by the

communicative event (field), the role-relationships of the participants (tenor) and the language acts

within the event (mode). Moreover, register variables interact with each other so that, for example

the overlap between tenor and mode gives rise to what Gregory and Carroll (1978: 53) call

"functional tenor", which is "the category used to describe what language is being used for in the

situation" – in other words, is the speaker/writer trying to persuade, exhort, inform and so on (or, to

put it another way, what is the communicative purpose of the text?) Ultimately, the key variable in

questions of register is the relationship between those communicating:

2

The language we use varies according to the level of formality, of technicality, and so on.

What is the variable underlying this type of distinction? Essentially, it is the role

relationships in the situation in question: who the participants in the communication group

are, and in what relationship they stand to each other. (Halliday 1978: 222)

Although cohesive relations are general to all kinds of texts, the forms taken by the cohesive

relations will differ according to the register – clearly, texture in conversation and in formal written

language is very different. Thus it is register, associated with classes of contexts of situation, that

defines what a text means. In other words, text as the basic unit of meaning in language has to be

interpreted in context and from a functional point of view.

Register studies

The discipline of register studies is perhaps most strongly associated with the work of Biber (1988,

1992, 1994), who uses register as a general cover term for all language varieties associated with

different situations and purposes (thus correlating with many definitions of genre, text type and

style). This broad concept of register is similar to that held by others, such as Gregory and Carroll

(1978: 4), who define it as "a contextual category correlating groups of linguistic features with

recurrent situational features". The purpose of register studies thus becomes the description of

situational and linguistic characteristics and the analysis of the functional or conventional

associations among these. The methodological approach recommended by Biber (1994) is the

analysis of co-occurrence patterns. The linguistic component of the analytical framework involves

searching for register markers, i.e. the distinctive features of particular registers, as well as

differing uses of core linguistic features. The lexical and grammatical features used for register

analysis include: tense and aspect markers, pronouns and pro-verbs, questions, nominal forms

(nouns, nominalisations, gerunds), passive forms, dependent clauses (complement clauses, relative,

adverbial subordination), prepositional phrases, adjectives, adverbs, lexical classes (e.g. hedges,

stance markers), modals, verb classes (e.g. speech act verbs, mental process verbs), reduced forms,

coordination, negation, grammatical devices for structuring info (e.g. clefting), cohesion markers

(including lexical chains), and the distribution of given and new information. Comprehensive

linguistic analysis of a register involves consideration of a representative selection of these features.

Such analyses are quantitative, because "register distinctions are based on the relative distribution

of linguistic features, which in turn reflect differences in their communicative purposes and

situations” (Biber op.cit. 35). This framework treats register as continuous rather than discrete; and

while some registers (such as personal letters) have well-defined norms, others (such as academic

prose) show considerable variation. Thus texts will vary considerably within some genres, but not in

others, while the registers themselves vary with regard to how much they are specified in relation to

different linguistic dimensions.

Accounting for the situational parameters of language variation is, of course, an extremely

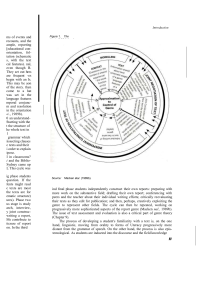

complex business, as the table in Biber (1994: 40-41) shows. This situational framework, which

draws in particular upon the work of Hymes (1967, 1974), Halliday (1978) and Crystal and Davy

(1969), has also been shaped by the thinking of corpus linguists. In order to specify the situational

characteristics of registers so as to distinguish between any pair of registers, seven parameters are to

be taken into account:

3

1. the communicative characteristics of the participants (e.g. single, plural, institutional)

2. relations between addressor and addressee (inc. social role, level of shared knowledge,

interactiveness, personal relationship)

3. setting (inc. place and time of communication, domain)

4. channel (inc. written vs. spoken, recorded vs. transient, medium of transmission)

5. relation of participants to the text (inc. production and comprehension circumstances,

personal evaluations, attitudinal stance)

6. purposes, intents, goals (e.g. persuasion, information transfer, entertainment)

7. topic/subject (inc. level of discussion, specific subject).

Without discussing it in great detail, a number of points need to made about this framework. One is

that some of the parameters, such as topic/subject and aspects of the participants' relation to the text,

are open-ended, rather than closed; moreover, many (such as purpose) are in reality clines or

continuums, rather than discrete values, and can also shift within a single text. The ultimate goal of

this framework within the context of register studies is the specification of quantitative values for

each parameter, expressed either in terms of ordinal scales (more-or-less relations) or dichotomies

(such as high/low, yes/no). Biber's (op.cit. 44ff) illustration of the situational characteristics of

eleven 'registers', is striking because of the disparate range of what the latter term includes – from

three types of letter (personal, professional, recommendation), through spoken modes (face-to-face

conversation, lecture, sermon), novels, narration (which Biber himself admits is not well-defined

situationally), and psychology article, to two types of prose (expository and academic). The

quantitative measurement of the correlation between linguistic dimensions and situational

parameters (or communicative functions) is further illustrated in relation to four of the registers just

mentioned, plus business telephone conversation and newspaper article. This shows the correlations,

expressed in numerical terms, between four situational parameters (mode, interactiveness, careful

production and informative purpose) and five varied linguistic features (contractions, that-deletions,

prepositional phrases, passives and varied vocabulary – expressed as type/token ratio) (cf. Biber

op.cit. 48ff).

Such studies of statistically significant lexico-grammatical features of different situational varieties

of language are a valuable analytical tool in that they provide empirical evidence to confirm or

undermine intuitive or impressionistic statements about registers. However, a checklist analysis does

not represent the ways writers and readers actually use texts: readers do not scan texts for particular

elements, while producing an acceptable text of a particular type is not a simple matter of

introducing the features required to mark it as a member of that type. The latter point naturally

applies equally to the process of translation, which is perhaps one reason why such an approach to

register has not had more influence within Translation Studies (further reasons are given when we

discuss text type, below). Moreover, as Bhatia (1993) points out, such analyses fail to provide

adequate explanations of why particular features are present or absent, or how information is

structured within a particular variety; nor do they explain how social purposes are accomplished

through genres.

Register vs. genre

The concept of genre has been taken by linguists from the field of literary studies, where it refers to

types of literary works (from poem, novel, short story, play, to sub-genres such as detective novel,

romantic novel, spy novel and so on), and broadened to include texts, both written and spoken, that

arise in a wide range of situations, including everyday transactions. In Martin's (1985: 250) words,

4

genres are "are how things get done, when language is used to accomplish them". 2 His examples

include lectures, seminars, recipes, manuals, service encounters and news broadcasts. His contention

is that registers are realised through language, while genres are realised through registers (and

registers are described in terms of configurations of Halliday's categories of field, tenor and mode)

Both he and Ventola (1984) also refer to register and genre as different semiotic planes, with genre

being the "content-plane" of register, while register is the "expression-plane" of genre. Eggins and

Martin (1997) identify register with context of situation and genre with context of culture, which

represent the two main dimensions within which texts vary. For Couture (1986), the two concepts

are also distinct: registers operate at the lexico-grammatical level, while genres operate at the level

of discourse structure.3 Genres are probably best seen as structured, (potentially) whole texts that

unfold in a particular way (a research or business report would be a good example), whereas

registers represent the more general linguistic choices that are made in order to realise genres (for

example, the language of scientific reporting or bureaucratic style). Thus genres have

complementary registers and the communicative success of a text depends on an appropriate

relationship to both systems.

Genre analysis

Genre analysis sets out to explain socio-cultural, institutional and organizational constraints upon

communication, as well as to identify conventionalized regularities in communicative events. In

particular, it examines the sui generis features of particular textual genres. The major work in this

field is by Swales (1990: 58), who defines a genre as:

a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative

purposes. These purposes are recognized by the expert members of the parent discourse

community, and thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. The rationale shapes the

schematic structure of the discourse and influences and constrains choice of content and

style.

A key concept here is that of discourse communities, which are "sociorhetorical networks" that

form in order to be able to work towards a common sets of rhetorical goals. The language activities

of such communities are thus driven by communicative purpose. Language is used within a group

as part of social behaviour to extend the group's knowledge and initiate new members. A discourse

community differs from a speech community in that it is geographically scattered (possibly

worldwide, as in the case of many academic communities) and writing based; moreover, it recruits

members by training, persuasion or qualification (not birth or accident). Its primary determinants are

functional: aimed at particular objectives. Swales (op.cit. 24-27) sets out six defining characteristics

of a discourse community:

1. has a broadly agreed set of common public goals (written or tacit);

2. has mechanisms on intercommunication among its members (meetings, reports, etc.);

3. uses its participatory mechanisms primarily to provide information and feedback;

2

This definition is, confusingly, not all that different from Gregory and Carroll's (1978: 64) and Couture's (1986: 80)

definition of register as "language in action".

3

Some of those working in the field of Translation Studies, such as Enkvist (1991), use the term discourse type instead

of genre – just as text type is often used to cover what we refer to here as genre.

5

4. utilises and hence possesses one or more genres in the communicative furtherance of its

aims (discoursal expectations are created by the genres that articulate the operations of

the discourse community);

5. in addition to owning genres, it has acquired some specific lexis (terminology, acronyms,

etc.);

6. has a threshold level of members with a suitable degree of relevant content and

discoursal expertise.4

The principal feature that turns a collection of communicative events into a genre is some shared set

of communicative purposes or goals (a communicative event is one in which language plays a

significant and indispensible role – the concept is a fuzzy one for which it is hard to draw exact

boundaries). Instances of genres vary in their prototypicality: a communicative purpose is the

privileged property of a genre; other properties, such as form, structure and audience expectations

operate to identify the extent to which an exemplar is prototypical of a particular genre (Swales

op.cit. 52). The rationale behind a genre establishes constraints on allowable contributions in terms

of their content, positioning and form. However, because a particular contribution is accepted and

labelled as belonging to a particular genre, it does not necessarily mean that it does – this is because

names for classes of events spread beyond the initial community into broader communities whose

criteria may differ. Swales goes along with Miller's (1984) description of genres as unstable entities,

the number of which is indeterminate in any society.5 Miller (op.cit. 151) also argues that the

definition of genre must be centred not on the substance or form of discourse but on the action it is

used to accomplish. An example is Fairclough's (1995: 14) characterization of a genre as "a socially

ratified way of using language in connection with a particular type of social activity". Moreover,

learning a genre involves learning not just a formal pattern or method of achieving a goal, but also

clarifying what are accepted as goals by the community within which we are operating (Miller

op.cit. 165).

Bhatia (1993: 16) takes his definition of genre from Swales, but places more emphasis on what he

calls the psychological factors and their influence on the way the writer constructs the text in

question: "each genre is an instance of a successful achievement of a specific communicative

purpose using conventionalized knowledge of linguistic and discoursal resources". In order to

succeed, the writer needs to conform to standard practices within the genre, although he/she may

have a great deal of freedom with regard to the use of linguistic resources. Experts in a particular

genre can exploit its conventions to achieve their private intentions within the socially-established

framework. Examples would be the experienced news reporter who can give a particular slant to a

supposedly objective news report, and the skilled counsel whose cross-examination in court is more

concerned with winning the case than bringing facts to the attention of the court. However, members

of the discourse community must be able to accept the text as an example of the genre for it to fulfil

its purpose. As a socio-culturally dependent communicative event, a genre is judged effective to the

4

But discourse communities can lose as well as gain consensus over time and break down into more than one

community. Hatim and Mason (1997: viii) observe that in what they dub the "modern communication explosion" genres

are evolving and influencing each other as never before and that departures from norms of language use are becoming

ever more frequent.

5

As examples, Miller (op.cit. 155) gives the letter of recommendation, the user manual, the progress report, the ransom

note, the lecture, the white paper, as well as those traditionally studied by rhetorical scholars, such as the eulogy, the

apologia, the inaugural, the public proceeding and the sermon.

6

extent that it can ensure pragmatic success in the context in which it is used (Bhatia op.cit. 39). It is

the shared communicative purpose that shapes the genre and gives it internal structure; any major

change to that purpose and a different genre is likely to result, while minor changes can help us to

identify sub-genres.

Genre analysis starts with the text in its context of situation. The socio-cultural and occupational

nature of the discourse community that uses the genre should be defined and, within it, the writer of

the text (individual or institutional), the audience, the relationship between them and their goals. We

also need to identify surrounding texts and linguistic traditions that form the background to the

genre, as well as identifying the topic or extra textual reality the text is trying to represent and the

relationship between the text and that reality. The genre under consideration may be analysed in

terms of communicative purpose, the situational context in which it is used and/or distinctive textual

characteristics. The actual linguistic analysis may concentrate on one or more of three levels:

lexico-grammatical features, text-patterning and structural interpretation (Bhatia op.cit. 24ff).

The second of these involves looking at how members of a discourse community assign restricted

values to various aspects of language use operating in a particular genre – what Widdowson (1979)

refers to as textualization. In doing so, we explain the function of particular linguistic features in a

specific genre, which helps us understand why members of secondary cultures write the way they

do: for example, the use of noun phrases in advertisements to facilitate the introduction of numerous

positive adjectives The third level of analysis highlights the cognitive aspects of language

organization. Members of discourse communities seem to be relatively consistent in the way they

organize their overall message in a particular genre. In order to explain this kind of structuring,

Swales (1981) uses the notion of rhetorical moves: thus, for instance, in a study of academic

research papers from a number of disciplines, he identifies a typical four-move structure that

characterizes the introductions to such texts. The move-structure in question is: 1. Establish the

research field, 2. Summarize the previous research, 3. Prepare for present research, 4. Introduce the

present research. Note that this structure is not prescribed: moves are representative options

available to an author within a particular genre, but they can be realised in different ways or not at

all.

From a cross-cultural point of view, it is worth noting that the genres most frequently discussed by

analysts (such as academic research papers by Swales, sales promotion letters and job applications

by Bhatia)6 tend to follow an Anglo-Saxon approach and so the move structure varies little between

languages. The field of science and technology, for example, in its "underlying infrastructure now

relies upon an English-based sociology of knowledge" (Grabe and Kaplan 1996: 156). In contrast to

the view generally held by scientists and laymen alike, scientific reporting is not all that objective,

but rather reflects deeply embedded cultural and rhetorical assumptions about relevance,

organization, acceptability and so on. The reality of scientific reports is constructed out of the social

relations within the research community, which tries to maintain its own coherence and the power

structure of the research community. As we have already noted, individuals use language either to

help them become members of such a discourse community, to cement relations with the

community, or to determine and define who they are and what they believe within the community.

6

See Connor (1996: 132ff) for discussion of a range of cross-linguistic genre studies, primarily in the fields of academic

writing (research articles, grant proposals), professional writing (CVs and job applications letters) business writing

(particularly letters) and newspaper editorials.

7

Publication is not about objective reporting, but about interpreting and modifying information, citing

authoritative literature and imitating appropriate models, with the aim of becoming, in turn, part of

the establishment and its literature. Thus science writing constitutes a value-laden rhetorical activity

(Grabe and Kaplan op.cit. 171) and to do it successfully you need a highly sophisticated sense of

audience, as well as an ability to convey rhetorically charged information – to be persuasive without

appearing to be so.

As far as translation is concerned, genre represents a useful way of looking at texts. The emphasis

on the acceptability of any generic instance within the discourse community echoes the concept of

acceptability within the target culture – as opposed to adequacy in relation to the source text – that is

central to descriptive translation studies (cf. Toury 1995). At the same time, the focus on

communicative purpose matches the emphasis on the aim or purpose of the target text within

Skopostheorie (cf. Reiss and Vermeer 1984; Vermeer 1978, 1989). In other words, both genre

analysis and two influential trends within Translation Studies are concerned primarily with the target

end of the communicative process and the way in which a text is received by its intended readership.

Text type and translation

The interest in text type within Translation Studies over the past few decades is to a large extent a

result of efforts to find a more satisfactory approach to translator training than one based on

sentential syntax and semantics. Approaches based on register analysis, which have tended to

involve selecting texts on the basis of broad contextual categories such as subject matter, and then

subjecting them to qualitative and/or quantitative analysis, fail to account adequately for the

communicative value of texts within a particular field and the "discoursal values lexico-grammar

relays in the course of communication" (Hatim and Mason 1997: 180). Put simply, text is more then

the sum of its parts – formality, for instance, is not only the statistical predominance of certain

lexical or grammatical features, and texts of similar formality within a field may display subtle,

though important differences. Similarly, the simple classification of text types in terms of field or

topic is not fruitful, nor are general labels such as 'journalistic' and domains such as 'literary'

particularly helpful.

Attempts to develop a more 'scientific' approach to translation based on text function are most

closely identified with the German translation theory tradition. One of the pioneers in this area,

whose initial concern was to try and develop a more objective approach to translation quality

assessment, was Reiss (1971, 1976, 1977).7 Her position is that the first step in assessing a

translation is to determine its text type – or, to be more precise, the text type of the source text –

only then can it be judged whether the translator had adopted an appropriate translation method. She

thus sets out to develop an exhaustive typology of texts "sensitive to the necessities of the translation

process" (Reiss 1971: 16). To achieve this, she draws upon Bühler's (1934) tripartite division of

language into representative, expressive and appellative functions to develop a schema of

informative (content focused), expressive (form-focused) and operative (appeal-focused) text types

(Texttypen), each identifiable by its dominant function (op.cit. 25-26). Each of Reiss's text types

7

Ironically, her key work in this area, Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Übersetzungskritik (1971), despite its influence in

Europe, has only recently been translated into English (in 2000, by Erroll F. Rhodes, under the title Translation

Criticism – The Potentials & Limitations. Manchester: St Jerome). Page numbers cited in this article refer to the English

translation.

8

includes different 'kinds' of texts (Textsorten), but these do not necessarily correlate with only one

text type; thus, for instance, a letter could be of any type, depending on its function.

In a subsequent book on the subject, Reiss (1976) tries to show how mixed forms emerge, but

retains the idea that it is the overall text type that decides what the translator should be trying to

achieve and the translation strategies to be employed in relation to both linguistic components

(semantic, lexical, grammatical and stylistic) and extra-linguistic determinants (place, time, subject

matter, audience, speaker). However, one obvious problem with Reiss's model is that it excludes a

whole range of 'special' kinds of translation (such as summaries, study editions, Bible translations,

interlinear versions and scholarly translations, as well as versions for children; see Reiss 1971: 92ff)

in which the text function changes to meet the needs of a particular situation or target audience – in

other words, the definition of translation used is a narrow and rigid one. This criticism can also be

made of the text type categories: for instance, it is questionable whether operative texts exist

independently of informative and expressive types. The reality is that texts are rarely monofunctional: multi-functionality, involving identifiable hierarchies of functions, is the norm. Finally,

as the discussion in Fawcett (1997: 107-108) shows, a fundamental weakness of the model is that

there is no necessary link between text type and translation method: there is no overriding reason

why the translator's decisions should be guided by the function of the source text.

The lack of a general rule here is acknowledged by Nord (1997: 39ff), who suggests that the

intended function of the target text serves as a useful guideline instead (although she admits that

the actual translations that result may not be that different from those guided by translation strategies

as old as those proposed by Cicero, Jerome or Luther). She sets out a model of text classification

that, like Reiss's, takes Bühler's model as its starting point, but adds a fourth 'phatic' function, drawn

from Jakobson (1960). The approach adopted by Nord, who is largely concerned at this point with

the practicalities of translator training, is a much more flexible one than Reiss's. It involves breaking

down the basic types into sub-functions, focusing on the way in which they are represented in texts,

and how this may relate to specific translation problems. Importantly, Nord (op.cit. 45ff) allows for

situations in which the function of the source text and that of the target text differ.

For Beaugrande and Dressler (1981: 186) a text type is "a set of heuristics for producing, predicting

and processing textual occurrences and hence acts as a prominent determiner of efficiency,

effectiveness and appropriateness"; they emphasize the fuzziness of text typologies and talk about

identifying 'dominances' rather than distinct types. From this as starting point, they define text type

in terms of predominant rhetorical purpose, which is the set of communicative intentions that

readers distinguish in a text on the basis of their experience with similar texts. Rhetorical purpose is

not the same as the writer's aim in writing: the aim of persuading, for instance, could be achieved

through narrative as well as through the presentation of argument. Hatim and Mason (1997)

distinguish three basic text types, each of which can be divided into sub-types as follows:

instruction, either without option (e.g. contracts, treaties) or with option (e.g. advertising);

exposition, divided into conceptual exposition (involving synthesis and analysis), narration (relating

to actions and events) and description (of objects and situations); and finally argumentation,

divided into through-argumentation (thesis cited to be argued through) or counter-argumentation

(thesis cited to be opposed). Such text typologies tend to give an impression of neatly defined

categories, but as we have already noted most texts are multifunctional and constantly shift focus –

hybridization is the rule, rather than the exception. However, Hatim (1997: 42) contends that there

9

is usually a dominant text-type membership, each text having a predominant and a subsidiary texttype focus. This echoes Werlich (1976), who identifies narrative, descriptive, expository,

argumentative and instructive text types and speaks in terms of each having a "dominant contextual

focus". However fuzzy text types are, we seem to have a system of expectations which are upheld or

defied in a motivated manner – a norm against which to judge motivated departures.

Neubert and Shreve (1992: 125ff) point out that while text type is somehow related to the

recognition of certain linguistic patterns, this always takes place against the background of a

communicative context. Thus text type is not a textual pattern but a set of expectations and

recognitions which must be used to generate the patterns according to the specific social situation.

They emphasize that the translator's "first order text types" are actually prototypes, i.e. "knowledge

structures applied in the production and interpretation of texts", which they distinguish from the

"analytical text types of text typologists" (Neubert and Shreve op.cit. 130). It is difficult to

characterize prototypes because they both determine and are determined by the social process;

moreover, they evolve dynamically through time, there is never a perfect balance between prototype

and social situation – though in some cases, such as legal texts, where communicative situations are

prescribed, textual instances become more static. However, this characterization of prototypes as

"particular ways of speaking and writing accepted at a particular time in history by particular

communicating subgroups" (op.cit. 132) give the impression that they are dealing with genre as

defined by Swales (1990). Yet they go on to reject textual categories such as patents, public notices

and injunctions, which would normally be thought of as genres, as unsatisfactory. They also criticize

other classifications – such as descriptive, narrative and argumentative – as "failing to capture the

social function of form and content" (ibid.). Their definition of prototypes is a hybrid one that leads

them to reject other systems of text classification as emphasizing specific aspects of textuality at the

expense of others.

With regard to text categorization, we can agree with Hatim and Mason (1990, 1997) that any model

must provide a sufficiently exhaustive approach to context, considering categories such as

intentionality, situationality and informativity (cf. Beaugrande and Dressler 1981), as this is

likely to be more successful in accounting for text type and for the diversity of rhetorical purposes

implicit in any communication. Moreover, the recognition of text type must be acknowledged as a

heuristic procedure involving not just the identification of rhetorical purpose, but also discoursal

(attitudinal meaning) and genre elements (conventional use of language appropriate to a social

occasion); and what is appropriate for a specific social purpose will vary between different

languages and cultures. Because of this, texts can never be neatly categorised, they often display

characteristics of more than one type and veer between points on the scale. Thus the text may

fluctuate between monitoring and managing the communication situation – i.e. the text producer

opts for a relatively detached account, or tries to steer the reader in a particular direction. This

characterises what is perhaps the most important factor in distinguishing between text types – the

degree of evaluativeness, which can be envisaged as a continuum from exposition to argumentation.

But superimposed on this is the scale of markedness, from 'static' to 'dynamic' language use, which

will also influence the approach taken by the translator (cf. Hatim and Mason 1997: 182-183, figures

11.1 and 11.2). But there are difficulties here, as highlighted in a report by Izquierdo (2000), who

notes that while her translation students found it relatively easy to identify genres in their mother

tongue because of their immediacy in the social environment, they had problems determining the

text type focus (argumentation, exposition or instruction) conveyed through such genres because of

10

the need for close reading and awareness of the linguistic devices used, and because of the multifunctionality of texts. Where genre and text type tend to coincide (e.g. advertisement and instructive

focus) the task may be more straightforward, otherwise detailed analysis of the text in context is

needed before its dominant focus can be identified.

One may expect different text types to place different demands on the translator. Thus in the case of

instruction, of which legal texts are a good example, there are a finite number of easy-to-learn

formulaic routines and the translator can opt for a fairly literal approach, unless there is a reason to

do otherwise. By contrast, exposition is more evaluative and less regulated than legal language, even

metaphor is possible, and semi-formality is permissible (this can be seen in a range of genres, from

abstracts to fairly evaluative kinds of reports). Finally, in the case of argumentation, which is

characterized by emotive diction, metaphoric expression and subtle modality, 'freer' translation is

often the only option (Hatim and Mason op.cit. 189ff). Text type only provides a framework for

translation choices, but the strategies employed have to be flexible – it is not a matter of making a

free vs. literal choice for a text. The reality is that interaction with texts is open-ended and so

translators constantly need to relate actual words to underlying motivations. It is also worth

reiterating here that in order to understand socio-textual practice (i.e. how a text functions in its

context of situation and context of culture), we also need to take into account both genre

conventions and discourse features, such as attitudinal meanings.8

Terminological uncertainty

Before concluding our discussion, we should say something about the terminological difficulties that

exist in this area, in both English and Slovene. Fawcett (1997: 105) refers to Reiss's Textsorten as

'text sorts', rather than 'text kinds' as in Rhodes' translation; however, this category seems to

correspond most closely to genre, as we have defined it above. In fact, many scholars writing in

English seem to make little distinction between these two categories, using 'text type' loosely to refer

both to text defined in terms of social purpose (genre) and rhetorical function. A similar level of

terminological uncertainty also exists in Slovene. Although the term žanr is normally reserved for

literary texts, some recent studies in contrastive rhetoric (e.g. Pisanski 2001) on occasion use it in

the same way as in the present study, perhaps under the influence of quoted texts in English.

Otherwise, besedilna zvrst is used to represent broad functional categories – or discourse types –

such as 'practical-communicative', journalistic, academic, literary (cf. Toporišič 1984: 623-624),

while (funkcijskozvrstni) vrsti are actual instances of these, corresponding to our use of genre – in

fact Toporišič (ibid.) treats the terms vrsti and žanri as interchangeable. At the same time, the

expression besedilni tip is also widely used (perhaps, again, under the influence of English and

German source texts), corresponding to either text type as we define it here (i.e. relating to rhetorical

function), or to genre. Finally, while registers are normally referred to as jezikovni zvrsti (cf.

Toporišič 1984: 10ff), the term register is also used, in particular when referring to the general

linguistic concept we discussed earlier.

8

In this way we can be sure of covering the textual, ideational, and interpersonal functions of language: generic

structures are "ideational in origin" (Hatim 1997: 31), while discourse accounts for the interpersonal component. We

should note here that Hatim (1997: 32) uses the term 'discourse' in a narrower sense to refer to the attitudinal,

interpersonal component of language use.

11

Conclusions

As is so often the case in both linguistics and translation theory, with regard to description of textual

variation there seems to be a distinct lack of agreement on the meanings of even the basic terms. So

what conclusions that we can draw from the mass of conflicting research evidence? The general

point is that each of the four terms in the title of our paper has a role to play within text and

translation analysis. Style is best reserved for judgements made by individual writers, which can be

judged in relation to norms – thus particular instances of language use can be described as

stylistically marked or unmarked. Although this is likely to be most applicable to literary texts, it is

also of relevance to any context where the writer's choices are of significance – for instance, in

political speeches or newspaper columns. Register reflects language use in different contexts of

situation, but the key variable involved is the relationship between those communicating; thus

register should not simply be equated with, say, subject matter or degrees of formality – the three

elements of field, tenor and mode always interact with each other. Genres are best understood in

terms of social action or communicative purpose – what we are using text to achieve. A text can be

taken as an example of a particular genre if readers accept it as such, which is why genres have been

referred to as socially ratified language use. It is useful to think in terms of genres being realised

through registers or of genres having complementary registers: whereas register operates at the

lexico-grammatical level, genres work at the level of discourse structure. Thus the communicative

success of a text depends both on its adherence to genre conventions and consistent use of

appropriate register. Finally, text type membership depends on predominant rhetorical purpose or

focus (e.g. instruction, exposition or argumentation). Genre and text type may coincide (as in legal

texts) and where they do the translator's task is easier, but usually individual genres will be hybrid in

terms of text type.

Bibliography

Beaugrande, R. de and Dressler, W. (1981) Introduction to Text Linguistics. London: Longman.

Bhatia, Vijay K. (1993) Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. London and New

York: Longman.

Biber, D. (1988) Variation Across Speech and Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D. (1992) ‘On the complexity of discourse complexity: A multi-dimensional analysis’,

Discourse Processes 15, 133-163.

Biber, D. (1994) ‘An analytical framework for register studies’. In Biber, D. and Finegan, E. (eds.)

Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 31-56.

Bühler, K. (1934) Sprachtheorie. Jena: Fischer. Translated by D.R.Goodwin (1990) as The theory of

language. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Connor, U. (1996) Contrastive Rhetoric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

12

Couture, B. (1986) 'Effective ideation in written text: a functional approach to clarity and exigence'.

In Couture (ed.) Functional Approaches to Writing: Research Perspectives. Norwood, NJ: Ablex:

69-92.

Crystal, D. and Davy, D. (1969) Investigating English Style. New York: Longman.

Eggins, S. and Martin, J.R. (1997) ‘Genres and Registers of Discourse’. In van Dijk, T. (ed.)

Discourse as Structure and Process. London: Sage: 230-256.

Faigley, L. and Meyer, P. (1983) 'Rhetorical Theory and Readers' Classifications of Text Types'.

Text 3: 305-325.

Fairclough, N. (1995): Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London:

Longman.

Fawcett, P.D. (1997) Translation and Language: Linguistic Theories Explained. Manchester: St

Jerome.

Grabe, W. and Kaplan, R.B. (1996) Theory and Practice of Writing. An Applied Linguistic

Perspective. London and New York: Longman.

Gregory, M. and Carroll, S. (1978) Language and Situation: Language Varieties and their Social

Contexts. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1970) 'Language Structure and language Function'. In Lyons, J. (ed.) New

Horizons in Linguistics. Harmondsworth: Penguin: 140-165.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1978) Language as a Social Semiotic. London and New York: Longman.

Halliday, M.A.K. and Hasan, Ruqaiya (1976) Cohesion in English. London and New York:

Longman.

Hatim, B. (1997) Communication Across Cultures. Translation Theory and Contrastive Text

Linguistics. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Hatim, B. and Mason, B. (1990) Discourse and the Translator. London and New York: Longman.

Hatim, B. and Mason, B. (1997) The Translator as Communicator. London and New York:

Routledge.

Hymes, D. (1967) 'Models of interaction of language and social setting', Journal of Social Issues 23.

Hymes, D. (1974) Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press.

13

Izquierdo, I. García (2000) 'The Concept of Text Type and Its Relevance to Translator Training',

Target 12 (2): 283-295.

Jakobson, R. (1960) ‘Linguistics and Poetics’. In T. Sebeok (ed.) Style in Language, Cambridge,

Mass: MIT Press: 350-377.

Leech, G.N. and Short, M.H. Style in fiction: A linguistic introduction to English fictional prose.

London: Longman.

Martin, J.R. (1985) 'Process and text: two aspects of human semiosis'. In Benson, J.D. and Greaves,

W.S. (eds.) Systemic Perspectives on Discourse, Vol. 1. Norwood, NJ: Ablex: 248-274.

Miller, Carolyn R. (1984) ‘Genre as social action’, Quarterly Journal of Speech 70: 151-167.

Neubert, A. and Shreve, G.M. (1992) Translation as Text. Kent, Ohio and London: Kent State

University Press.

Nord, C. (1997) Translation as a Purposeful Activity. Manchester: St Jerome.

Pisanksi, A. (2001) Angleško-slovenska kontrastivna analiza nekaterih metabesedilnih elementov v

znanstvenih besedilih. Magistrsko delo. Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta.

Reiss, K. (1971) Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Übersetzungskritik. Munich: Hueber. Translated by

Erroll F. Rhodes (2000) as Translation Criticism – The Potentials & Limitations. Manchester: St

Jerome.

Reiss, K. (1976) Texttyp und Übersetzungsmethode: Der operative Text. Kronberg: Scriptor.

Reiss, K. (1977) 'Texttypen, Übersetzungstypen und die Beurteilung von Übersetzung', Lebende

Sprachen 22 (3): 97-100. Translated as 'Text types, translation types and translation assessment'

in Chesterman (ed.) 1989: 105-115.

Reiss, K. and Vermeer, H. (1984) Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationtheorie. Tübingen:

Niemeyer.

Snell-Hornby, M. (1988) Translation Studies. An Integrated Approach. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

(Revised edition 1995.)

Swales, J.M. (1981) Aspects of article introductions. Birmingham, UK: The University of Aston,

Language Studies Unit.

Swales, J.M. (1990) Genre Analysis. English in academic and research settings. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Toporišič, J. (1984) Slovenska slovnica. (2nd edition) Maribor: Obzorja.

14

Toury, G. (1995) Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John

Benjamins.

Ventola, E. (1984) 'Orientation to Social Semiotics in Foreign Language Teaching'. Applied

Linguistics 5: 275-286.

Vermeer, H. J. (1978) 'Ein Rahmen für eine allgemeine Translationestheorie', Lebende Sprachen 23

(1): 99-102.

Vermeer, H. J. (1989) ‘Skopos and commission in translational action’. In Chesterman (ed.): 173187.

Widdowson, H.G. (1979) Explorations in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Werlich, E. (1976) A Text Grammar of English. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.

15

Summary

The paper discusses varying definitions of the terms text type, genre, register and style, and suggests

how they can be used to describe situational variation among texts. This survey includes an

overview of the disciplines of register studies and genre analysis, as well as efforts within

Translation Studies to define text type. Each of the four terms has a role to play within text and

translation analysis. Style is best reserved for judgements made by individual writers, which can be

judged in relation to norms. Register reflects language choices in different contexts of situation, but

the key variable involved is the relationship between those communicating. Genres are best

understood in terms of social action or communicative purpose – what we are using text to achieve.

The communicative success of a text depends both on its adherence to genre conventions and

consistent use of appropriate register. Finally, text type membership depends on predominant

rhetorical purpose or focus (e.g. instruction, exposition or argumentation).

TIP IN VRSTA BESEDILA, REGISTER TER STIL V ODNOSU DO ANALIZE IN

PREVAJANJA BESEDIL

Povzetek

Avtor obravnava različne definicije izrazov besedilni tip, besedilna vrsta, register (jezikovna zvrst)

in stil ter njihovo uporabo pri opisih situacijskih variacij v besedilih. Vključen je tudi kratek opis

analiz registra in besedilnih vrst ter različnih poskusov definicij besedilnih tipov v okviru

prevodoslovja. Vsak od navedenih izrazov igra svojo vlogo v analizi besedil in prevodov.

Poudarjeno je, da je izraz stil najbolje uporabiti za specifični jezikovni izbor posameznega avtorja,

ki ga lahko ocenjujemo v primerjavi z ustaljenimi normami. Register odraža izbiro jezika v različnih

situacijskih kontekstih, ključna spremenljivka pa je razmerje med sogovornikoma. Besedilno vrsto

je najbolje razumeti z vidika družbenega dejanja oziroma sporočilnega namena – kaj želimo doseči z

besedilom. Avtor ugotavlja, da je sporočilni uspeh besedila odvisen tako od tega, v kolikšni meri se

drži konvencij besedilnih vrst, kot tudi od dosledne uporabe primernega registra. Besedilni tip pa je

odvisen od prevladujočega retoričnega namena oziroma poudarka besedila (n.pr. usmerjanje

[instruction], ekspozicija ali argumentacija).

16