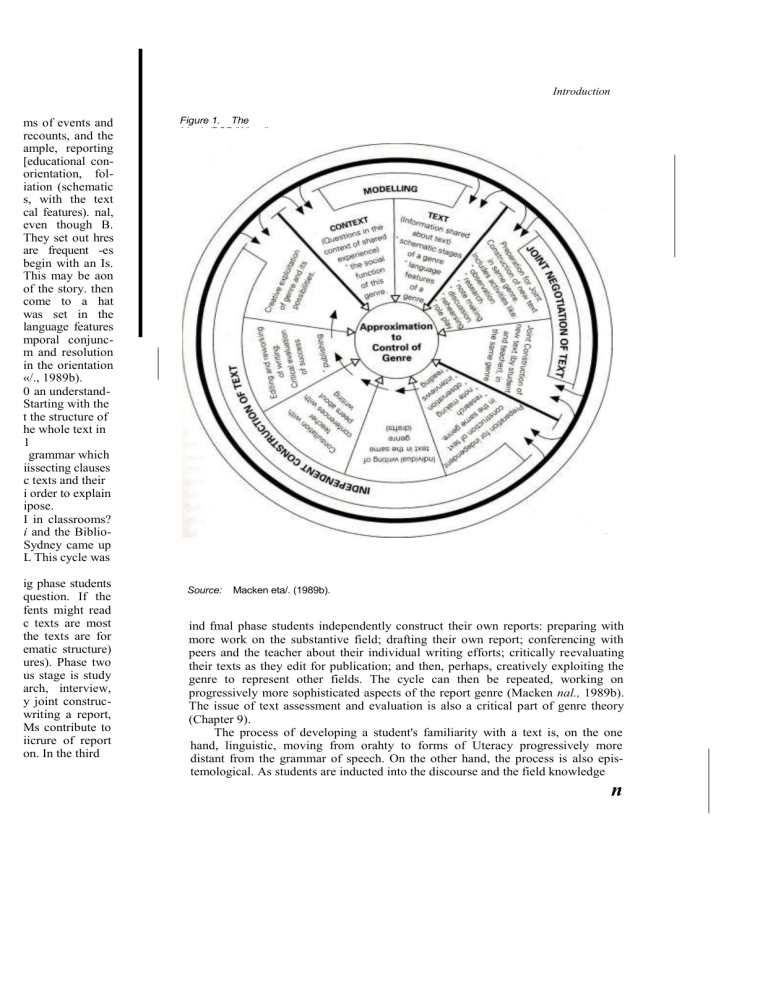

Introduction Figure 1. The Martin/DSP `Wheel` Model of Genre

Introduction ms of events and recounts, and the ample, reporting

[educational conorientation, foliation (schematic s, with the text cal features). nal, even though B.

They set out hres are frequent -es begin with an Is.

This may be aon of the story. then come to a hat was set in the language features mporal conjuncm and resolution in the orientation

«/., 1989b).

0 an understand-

Starting with the t the structure of he whole text in

1

grammar which iissecting clauses c texts and their i order to explain ipose.

I in classrooms? i and the Biblio-

Sydney came up

L This cycle was ig phase students question. If the fents might read c texts are most the texts are for ematic structure) ures). Phase two us stage is study arch, interview, y joint construcwriting a report,

Ms contribute to iicrure of report on. In the third

Figure 1. The

Martin/DSP 'Wheel'

Model of Genre

Literacy Pedagogy

Source: Macken eta/. (1989b).

ind fmal phase students independently construct their own reports: preparing with more work on the substantive field; drafting their own report; conferencing with peers and the teacher about their individual writing efforts; critically reevaluating their texts as they edit for publication; and then, perhaps, creatively exploiting the genre to represent other fields. The cycle can then be repeated, working on progressively more sophisticated aspects of the report genre (Macken nal., 1989b).

The issue of text assessment and evaluation is also a critical part of genre theory

(Chapter 9).

The process of developing a student's familiarity with a text is, on the one hand, linguistic, moving from orahty to forms of Uteracy progressively more distant from the grammar of speech. On the other hand, the process is also epistemological. As students are inducted into the discourse and the field knowledge n