Salvatore JA Sclafani, MD, FSIR

advertisement

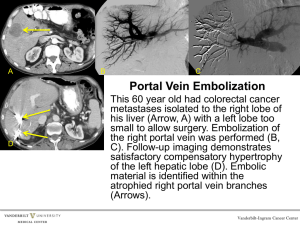

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Intravascular Ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency Salvatore J.A. Sclafani, MD, FSIR American Access Care Physicians Professor of Radiology, Surgery and Emergency Medicine State University of New York Downstate Medical School Brooklyn, New York 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Introduction 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 The primary venous conduits that constitute the cerebrospinal venous circuit include the right and left internal jugular vein (IJV), the right and left vertebral veins and the azygous vein. These are the major outflow veins of the brain and the spinal cord draining venous blood from the dural sinuses and from the vertebral plexus and spinal veins. There are also secondary outflow veins, namely the innominate veins and the superior vena cava. Augmentation of the primary outflow veins can result from obstruction of the "inflow" veins that are connected to the primary veins. These include the left renal vein that is connected to the hemiazygous vein and the left common iliac vein that is connected to the ascending lumbar vein. 29 30 31 32 33 The recommended diagnostic algorithm utilizes Doppler ultrasound of the deep cerebral veins, the IJVs and the vertebral veins in both the erect and supine positions to assess the hemodynamic consequences of outflow derangement and B-mode ultrasound to detect structural abnormalities. Doppler hemodynamic manifestations include reversal or absence of flow and loss of normal postural Chronic Cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) is a clinical syndrome that results from outflow resistance of the veins that drain the brain and the spine. It presents with chronic fatigue and temperature intolerance, short term memory deficiencies and problems of concentration and executive processing, headaches, spasticity and vision deficiencies, among others (1-3). CCSVI is most commonly seen in patients with multiple sclerosis (4), but these symptoms have been reported in patients with jugular stenoses and occlusions caused by radical neck surgery, vascular access catheters, tumor compression, hypercoagulable states, and trauma and without antecedent cause. (5-8) 34 35 36 37 control in the erect position. A variety of B-mode abnormalities can be seen, including occlusions, stenoses and hypoplasias, thickened, elongated and immobile valves, septum and membranes. The detection of at least two of five criteria correlates highly with the presence of CCSVI. (9) 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and computed tomographic venography (CTV) have been used by some to screen for CCSVI. These examinations allow non-invasive visualization of the entirety of the veins of the neck, but in addition can detect stenoses, hypoplasias and occlusions of these veins. Moreover these imaging methods allow visualization of the central chest veins and the dural sinuses prior to venography. Additionally, some efforts have been made to quantify flow selectively in each of these critical veins. 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 Venography remains the Gold Standard for the visualization of the jugular veins, as well as of the azygous vein, a vein that cannot be imaged satisfactorily by MRV, CTV or Ultrasound. To its advantage, venography can also visualize the secondary veins, such as the left renal vein, the left common iliac vein and the ascending lumbar vein. Venography can also assess subjectively flow, stasis and reflux in these veins. To its advantage, the catheter study enables subsequent treatment by angioplasty of stenoses of these veins. 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 However, each of these imaging modalities has deficiencies that can negatively influence treatment decisions. Surface ultrasound cannot visualize well the confluens of the internal jugular vein and the subclavian vein because of the impediment of the clavicle. Angling the transducer into the chest may underestimate disease in this area. This is a critical deficiency because the area under the clavicle is the most common location for pathology in CCSVI. Similarly, the upper cervical jugular vein and the jugular bulb cannot be visualized by ultrasound because of the limited acoustical window resulting from the spine, mandible and skull. Moreover it is clear that ultrasound can evaluate completely neither the azygous vein nor the brachiocephalic veins. In addition assessing the degree of stenosis is unreliable by ultrasound. 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 MRV and CTV cannot evaluate intraluminal pathology, such as the immobile valves, webs, septations, membranes and duplications. As with ultrasound, they cannot evaluate satisfactorily the azygous and hemiazygous veins even though they are able to identify the compression syndromes of the renal vein and the iliac vein. Furthermore they often detect spurious stenoses that are not confirmed by venography. These stenoses may represent transient phasic narrowings or may result from diminished flow above true stenoses commonly located at the confluens region of the vein. 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 Similarly venography also has difficulties identifying the intraluminal pathology because density of the injected contrast may obscure these findings. Moreover venographic determination of the size of the veins is rather subjective and may mislead without multiple projections that would be necessary to assess this characteristic. The IJV is often not a circular object; rather it is oval or complex in shape. Thus determination of the diameter of the vein if often arbitrary and often underestimates or underestimates the proper size of balloon for angioplasty. In light of the high pressures necessary to disrupt this internal pathological stenosis, proper sizing is crucial to avoidance of injury to the vein by overdilatation or early recurrent stenosis by underdilatation. 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 All of the luminographic studies, such as venography, MRV and CTV, suffer from their "snapshot" nature. Outflow obstruction of the jugular veins results in slow flow or stasis. Because there is an alternative cerebral outflow via the vertebral veins, decompression results in diminished IJV volume these thin walled IJVs that can collapse against rigid structures such as the spine, the carotid artery and neck musculature. Accurate depiction of these veins requires multiple views, such as imaging during inspiration and expiration, during flexion and extension, and during rotations of the neck. These maneuvers cannot be done in real time by MRV and CTV and doing them during venography is time-consuming to the operator and results in increased radiation dose to the patient. 91 Intravascular Ultrasound 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 Intravascular ultrasound provides benefits that can address many of the deficiencies of venography, surface Duplex examination, CTV and MRV. The most common indications for intravascular ultrasound have been in the evaluation and treatment of arterial disease, notably in the management of coronary artery disease. Its ability to differentiate various tissue characteristics enables one to assess plaque morphology, detect lipid and calcium deposits and elaborate the degree and distribution of calcification within atherosclerotic plaques. It can thus help evaluate the vulnerable soft, un-ruptured plaque. IVUS is useful in characterization of both the vessel wall and the endothelium. It can assess mural and endothelial thickness and clarify whether narrowings are the result of intimal or mural disease. 103 104 105 106 107 IVUS has been shown to provide a more accurate assessment of vessel circumference and cross sectional area and thus is useful in detecting critical stenoses. Such elegant analysis of the dimensions of the vessel allows a more accurate selection of balloon size, thus reducing risk of injury and providing more effective angioplasty. IVUS allows improved visualization of intimal thickening 108 109 110 111 after angioplasty. Moreover, IVUS enables the operator to see how well apposed stents are to the intima and thus guides the need for additional angioplasty to reduce separation between intima and stent. This may facilitate endothelialization of the stent. 112 113 114 Although the vast majority of publications on IVUS relate to the coronary arteries, authors have reported on the value of IVUS in many other conditions, both within arteries and veins. (10) 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 More recently, benefits have been reported in a number of peripheral arterial applications. Some of the same advantages of IVUS have been exploited in the treatment of peripheral atherosclerotic disease (11). Plaque morphology, more accurate determination of vessel size and degree of stenosis, and tissue characterization by IVUS have been added to the information from angioplasty and thus facilitating and enhancing atherectomy and stenting of peripheral, renal and carotid atherosclerosis. (12) 122 123 124 125 126 127 Authors have also been enthusiastic about using IVUS in the deployment of aortic endographs. More accurate measurement of vessel circumference and the sonographic visualization of the location of aortic branches have allowed greater precision in determining both upper and lower landing zones. The addition of IVUS can alter the plans derived by CTA, contradicting CT’s determination that endovascular stenting was either feasible or futile. 128 129 130 131 132 IVUS has been shown to facilitate the diagnosis of aortic dissection. It is highly effective in detecting entry points along the dissected aorta. This can facilitate placement of stents and reduce need for operative intervention. Moreover, IVUS has been shown to be an effective guidance method during fenestration procedures. (13-15) 133 134 135 136 137 The use of IVUS in cases of traumatic aortic injury has been shown to improve diagnosis, especially in patients with equivocal aortography, by allowing differentiation of ductus diverticulum and pseudoaneurysm. Indeed, it was shown to be superior to aortography in one series of fourteen patients with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 100%. (16) 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 While much less commonly reported than use in arterial disease, IVUS has shown merit in a variety of venous pathologies and treatments. Because of its portability, IVUS as a guidance method has been recommended for placement of inferior vena caval filters. The ability to precisely determine the circumference of the caval lumen and to localize all renal vein tributaries without contrast media or ionizing radiation has advantages. Filters can be deployed in an intensive care unit, thus avoiding risks of transport of critically ill patients. The ability to perform 145 146 the procedure without the use of iodinated contrast media is such patients is a distinct advantage. 147 148 149 150 The use of IVUS for venous disease in patients with renal insufficiency or in patients with potentially life threatening allergies to contrast media has also been reported in management of dialysis grafts and fistulae, and central venous stenosis. (17-18) 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 Negen and Raju have argued effectively for the use of IVUS in patients with venous disease, notably in chronic iliac vein stenosis and occlusions. They point to the fact that hemodynamic data so helpful in arterial obstructions is often limited or equivocal in venous disease because of small differences. The significance of pull-through pressure gradients is difficult to interpret. Small degrees of pressure differential may indeed be significant, given the large volumes and high compliance. Rather morphological area stenosis of 50% seems to provide some predictive value of clinical improvement after angioplasty. They recognize the rather irregular shape of the iliac vein and the difficulties in using single view diameters to make stenosis measurements. Further they point out that intraluminal abnormalities, such as immobile valves, subintimal edema, and echogenic material, probably representing trabeculae, septa, and webs, cannot be seen by venography which obscures them with dense contrast media. (19-21) 165 166 167 To date I can find nothing in the literature that describes the IVUS findings of CCSVI, nor one that reports on abnormalities of the internal jugular vein and the azygous vein in CCSVI or other diseases. 168 Technical considerations 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 Intravascular ultrasound is a technique that places within a hollow structure, such as a vein or artery, a catheter or a wire containing a miniaturized phased array ultrasonic transducer that sends out frequencies of 10 to 50 megahertz and then captures reflections off near objects. The catheter or wire is 3.2-8.2 French in diameter and is attached externally to a cart that performs the reformations and calculations. The systems are also equipped with a motorized unit that can retract the catheter at a fixed rate. The device can be introduced through a sheath of 6-9 Fr diameters and advanced over a 0.01inch-0.038 inch guidewire by either over the wire or rapid exchange techniques. (11) 178 179 180 Images that are created are cross sectional B-mode images with resolution of 110-150 microns and penetration of about 20 millimeters. In addition to cross sectional images, modern units can create longitudinal reformations that some 181 182 183 184 185 186 believe provide images that are more revealing views of length of stenosis and degree of narrowing. However, this requires use of a motorized catheter driver. Some vendors have now made available wires that can capture hemodynamic data such as Doppler flow rates, pressures and gradients. Assessment of stenotic and microvascular resistance is now possible, although the utility of this information in CCSVI is not established. 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 Other methodologies include ChromaFlo and VH (Virtual Histology). Chromaflow detects blood flow and represents it on imaging with a red color. Thus this nonquantifiable presentation of flow aids in differentiating tissue types that are similar to flowing blood on the B-mode images. VH-IVUS is a spectrum analysis of IVUS-derived radiofrequency (RF) data acquired at the top of the R wave. It allows reconstruction of a color coded map showing a more detailed analysis of plaque composition and morphology. It is suggested that VH-IVUS has the ability to detect lesions that predict high risk lesions in coronary artery disease. It is possible that such manipulations may distinguish various tissue types in CCSVI and may be able to predict response to angioplasty. However this feature does not yet exist. 198 199 200 201 202 203 Finally, IVUS presents a real-time cross sectional view. During that interrogation it is possible to analyze various questionable areas of the venous anatomy while performing a variety of physiological maneuvers such as Valsalva and reverse Valsalva, inspiration and expiration, flexion and extension and varying degrees of rotation. We shall see that there is great advantage to such maneuvers in the evaluation of CCSVI. 204 Justification for IVUS in CCSVI 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 IVUS is indicated as a primary evaluation of intraluminal venous pathology, as a tool for stenosis analysis, as a method of detecting pressure gradients, as an aid for assessing inconstant or atypical narrowings and as a post-angioplasty exam. In unusual circumstances, IVUS can allow the procedure without use of iodinated contrast media in patients who have had potentially life-threatening allergic reactions to contrast media or who have severe renal insufficiency but do not yet require chronic hemodialysis. IVUS can provide sufficient information to perform this procedure without venography although venography does make this procedure easier. 214 215 216 217 A recent presentation of a joint meeting of the European Committee on Research in MS (ECTRIMS) and the American Committee on Research in MS (ACTRIMS) reported on a comparison of jugular venous pathology from specimens obtained at autopsy from cadavers of patients with multiple sclerosis 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 and of people who died of unrelated illness. (22) The authors discovered that stenoses were common in both group. What distinguished the MS group from the non-MS group was a preponderance of intraluminal lesions, such as immobile or inverted valves and other valvular deformities, septum, webs, membranes and duplications. This is consistent with the theory that CCSVI is the result of malformation of the maturation of the fetal cardinal system of cerebrospinal veins into the adult system (23). 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 The preponderance of intraluminal lesions suggests that an intraluminal study is appropriate for the complete diagnosis of this pathology. Venography can demonstrate the major stenotic lesions. However superimposition of valvular cusps and reflux opacification of the vessel distal to a stenosis may obscure them. Moreover, venography cannot distinguish the various etiologies of such stenoses. Strictures, hypoplasia, and valvular stenosis can look identical on venography which provides a simple lumenogram. Endoluminal studies are superior to contrast studies that obscure such pathology by the necessary density of the contrast media. Negen and Raju have shown evidence that such venous pathology in the iliac vein is unrecognized by venography and yet well seen by IVUS. (21) 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 IVUS is also valuable in evaluating transient narrowings that are not fixed and may be physiological. Moreover veins often have irregular circumference; compressed by surrounding muscles, arteries and bones they may take varied and unusual contours that make it difficult to determine their diameter. As such, stenosis analysis may be extraordinarily difficult and inaccurate. Simple diameter measurements rarely provide a good maker of stenosis. Nor are such diameter measurements sufficient to choose an appropriate balloon size for angioplasty. Finally IVUS provides an excellent methodology of evaluating the effectiveness of venoplasty and valvuloplasty. The elimination of immobile valves is particularly well seen on IVUS. Complications of angioplasty are also better visualized by IVUS. Thrombus and dissections are readily seen on IVUS. 247 Performing the examination 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 I perform diagnosis and treatment of CCSVI using fluoroscopy, venography, intravascular ultrasound and external ultrasound access guidance. The procedure is performed under local anesthesia and with micropuncture access. Vascular entry is obtained under external ultrasound guidance through a left inguinal approach, to enter the saphenous vein at the saphenofemoral junction. A 10 French sheath is introduced and positioned above the right atrium in the superior vena cava. The sheath is positioned and all instrumentation is moved 255 256 through the sheath, as an essential protection because the very small wire required to track the IVUS buckles into the heart and mat cause arrhythmias. 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 Once the sheath is in place, all, or at least most, of the catheterizations are performed over the 0.014 inch guidewire needed for the IVUS. I perform venography followed by IVUS for each of the three major cerebrospinal outflow veins, namely the right and left IJV and the azygous vein. I perform venography alone in the majority of transverse sinuses, in the left renal vein, in the left common and external iliac vein and in the left ascending lumbar vein. I do not recommend routine IVUS of the left renal vein or the left iliac vein because these veins are rarely associated with immobile valves. However when stenoses or prominent collaterals are identified, IVUS is used. When compression of the renal or iliac veins is seen, the diagnosis of Nutcracker or May Thurner syndrome can be made. IVUS is then critical to accurate sizing of these veins to reduce risk of migration. 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 With the guidewire in the transverse sinus and using a rapid exchange system, the IVUS is positioned in the jugular bulb and then withdrawn manually at deliberate speed down into the innominate vein. I do not use the automated pullback device because such devices were developed for coronary use and the pull back moves too slowly to be practical for the long length of the jugular vein. Critical areas to evaluate include the upper internal jugular vein at the C-2 level, the mid jugular vein where venous compression by the carotid artery or the strap muscles occurs and, most importantly in the lower jugular vein at the confluens with the subclavian vein where most of the pathology is located. (Figure 1) 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 After azygous venography IVUS is performed throughout the azygous vein, extending as far down the azygous and hemiazygous as possible. Transient narrowings are common in the azygous. Inspection of narrowings throughout the ascending azygous should include inspiration and expiration views as this area common dilates during inspiration. I do not treat transient narrowings. The area of the junction of the ascending azygous and its arch is inspected in great detail. Subtle immobile valves in the azygous vein are often unrecognizable on venography and are often visualized only by IVUS. (Figure 2) 286 287 288 289 290 291 B-mode imaging in both the cross sectional and longitudinal views are important. The cross-section image looks at the circumference of the vein, and reflective tissue such as webs, membranes, septums and valves. The longitudinal view gives a good view of collateral entries, longitudinal views of stenoses and a different view of intraluminal pathology. I have not relied upon ChromaFlo or Virtual Histology at this time. 292 Diagnostic IVUS: findings 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 Normal Internal Jugular vein (Figure 1) 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 On IVUS, the IJV varies in its appearance depending upon location in the neck. The upper segment (J3) starts as a larger structure (superior jugular bulb) that quickly diminishes in circumference. It occasionally flattens as it courses over the second cervical vertebra before expanding in diameter in the mid portion of the neck (J2). Often tributaries are seen in this region. A second crescentic indentation, representing the compression by the carotid artery, may be seen in this region. The lower jugular vein is normally dilated as it joins the subclavian vein (inferior bulb). 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 Normal Azygous venous system (Figure 2) 323 324 325 326 327 328 The azygous vein is a continuation of the right ascending lumbar vein; the hemiazygous vein is a continuation of the left ascending lumbar vein or a branch of the left renal vein. The accessory hemiazygous vein is a continuation of the upper left intercostal veins and may drain into the left innominate vein or into the azygous vein. Valves are typically present in the arch of the azygous vein; they may be multiple. The IJVs are the primary venous outlets for the cerebral blood volume when a human is supine. The vertebral veins and the vertebral plexus assume this function in the erect position. The sigmoid sinus, the terminal component of the transverse sinus, combines with the inferior petrosal sinus to form the superior jugular bulb. The vein runs a continuous course down the neck in the lateral aspect of the carotid sheath where it dilates (inferior bulb) before enter the innominate vein at its confluens with the subclavian vein. Valves, usually biscuspid, are located near the confluens are present in about 85% of humans and. There may be more than one set of valves. Major branches of the IJV include the inferior petrosal sinus, pharyngeal vein, the common facial vein, the lingual vein, and superior and middle thyroid veins. In CCSVI IJV outflow is compromised The azygous vein is a critical conduit that drains the thoracic and, to some degree, the lumbar spinal venous circulation. The central and radial spinal veins, draining via vertebral plexuses and anterior and posterior medullary veins ultimately form intervertebral veins that connect with intercostal veins before draining into the azygous and hemiazygous veins. These spinal veins and plexuses are connected directly to the venous drainage of the brainstem and the cervical and lumbar spinal cord, via anterior and posterior medial spinal veins and dural plexuses. 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 On IVUS the azygous vein is usually a rounded structure with little sonolucency in the wall as all veins have minimal muscularis. At the level of the aorta, the vein may be flattened or narrowed. One sees segmental veins entering it; segmental arteries are posterior to the vein and may temporarily indent the vein. At the junction of the ascending azygous vein with the arch of the azygous, a large draining vein may enter it. This is the continuation of the accessory hemiazygous vein. Valves are usually present within the arch of the azygous vein. When thickened they are visible, echogenic and show limited motion. 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 Abnormal 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 Assessment of all valvular structures is very important as the majority of abnormalities are located in areas of valves and most abnormalities are malformations of valves. Intraluminal bright signals can be misinterpreted as artifacts but they should be considered very carefully. Moving the transducer and then returning to the same area looking for the persistent bright reflections in the same location is a helpful tool in eliminating artifacts from serious consideration. The examination is reviewed both in cross sectional view and in the longitudinal mode. 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 Valves (Figure 3) Venography provides a comprehensive technique for detection of stenoses of the major cerebrospinal veins. These stenoses are usually well seen on contrast studies. However, the nature of such stenoses may be less clear. IVUS provides important data regarding the nature of stenoses: the anatomic nature of stenoses, the phasic nature of stenoses and whether they are intrinsic or extrinsic in nature. Normal valves are almost imperceptible: gossamer structures that are not easily visible. Abnormal valves are more easily seen. They are characterized by irregular thickening, poor mobility and bulging cusps. Thickening may be small foci of echogenic spots measuring less than a millimeter or longer areas of thickening. These are highly echogenic. These thickened areas may form a circular or oval circumference. The circumference may progressively decrease as the transducer is moved down the vein toward the chest. The valve appears to sway to and fro. One sees that the edges of these valves move little and never extend to the lateral walls of the vein. Uncommonly the valve may be seen en face at one level. On the longitudinal view, the lumen may be narrow and there may be two parallel signals (the “double echo" sign) that represent echoes off the valve and off the outer wall of the vein. 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 Septum (Figure 4) 377 378 379 380 381 Membrane (Figure 5) 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 Web (Figure 6) 392 393 394 395 Thrombus (Figure 7) 396 397 398 399 400 401 Diffuse narrowings Septums are seen as thin vertical bands extending up and down the vein. They may be thin or have areas of patchy echogenicity similar to the leaflets of valves. They may be compared to elongated valve leaflets. One can sometimes follow these bands to their attachment to the wall proximally or distally, forming a sort of "windsock". Some septum form a blind ending sack dividing the vein into two separate chambers, only one of which is in continuity with the cephalad lumen, analogous to a dissection. The "false" lumen may bulge and compress the "true" lumen on Valsalva maneuver. Septum may also show thickening and increased echogenicity, similar to abnormal valves. Differentiation relies upon the absence of an opposing valve leaflet. The septum appears to be taut against the IVUS probe. A membrane is a horizontal band of tissue, like a valve that extends transversely across the vein as well. On the longitudinal view, septum shows as relatively thin lines of tissue running parallel to the venous wall. They may be very difficult to visualize on IVUS because of their horizontal nature. Webs are bands of tissue remaining within the lumen of the vein. They are thought to be sequellae of the de-differentiation/re-differentiation of the veins during the transition from the fetal cardinal system into the adult system. Webs are another abnormality that is often not recognizable by venography because of its location within the lumen. Webs are represented as echogenic material within the vein lumen that is persistent and located in the same location during several interrogations with the IVUS probe. They are most commonly seen within the azygous vein and less commonly in the jugular system. On longitudinal view they are usually seen as random areas of high echogenicity. Thrombus is another echogenic material within the lumen. Clot tends to be thicker and amorphous and has a speckled and more brightly echogenic character. It is also inconstant in location and less reproducible. Intravascular ultrasound is very useful in assessing and differentiating the many causes of long narrowed segments Diffuse luminal narrowing can be a phasic, inconstant phenomenon or it can be caused by compression syndromes, by hypoplasia, by intimal hyperplasia or by post-thrombotic recanalization. Each of these presents venographically as a narrow contrast column. Differentiating 402 403 these problems is sometimes challenging but important as different treatment strategies are warranted. Treatments vary from doing nothing to stenting. 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 Inconstant narrowing (Figure 8) 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 Venography, as a static sequence, does not allow dynamic imaging because of time constraints and radiation exposure. Imaging with IVUS is free from these impediments and allows one to place the transducer at the point of interest and perform a variety of maneuvers. Maneuvers that increase flow by activation of the thoracic pump, such as deep expiration, may increase flow through the vein. Changing neck position, such as flexion and extension, internal or external rotation may reduce flow by increasing the pressure on the IJV. 419 420 421 422 423 424 Other compressions are more significant and IVUS can plan an important role in their evaluation. The Nutcracker and the May-Thurner syndrome are clinically manifested obstruction of the left renal vein and left common iliac vein that are caused by compression of these veins between two structures. IVUS shows complete flattening of the vein, associated with a prominent hemiazygous, or renal vein or, is 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 Long luminal narrowings (Figure 9 ) 433 434 435 436 437 438 However, IVUS has the potential to differentiate these problems, based upon the echogenicity of the offending pathology. Hypoplasia shows a narrow lumen but the echogenicity of the wall may be normal. In a recanalized vessel, IVUS may show intraluminal thrombus lining the interior of the vein. Thrombus is highly echogenic and often can be differentiated from the reflections of the wall itself. The echogenic areas may be interspersed with areas of diminished echogenicity. Inconstant narrowings are a physiological effect frequently associated with fixed stenoses that are located more centrally in the vein. The dual outflow system of the cerebral venous system through the internal jugular veins and the vertebral veins and vertebral plexus allows the obstructed vein to decompress. Because of the compliance of the veins, the vein can collapse. Such collapse may be more pronounced due to pressure upon this vein by the internal or common carotid artery or compressed by muscles. Long luminal narrowings may be caused by hypoplasia, intimal hyperplasia, postthrombotic recanalization, or perivenous inflammatory processes. Venographic appearance of these entities can be virtually indistinguishable. When the luminal diameter is completely collapsed, differentiation of these abnormalities can be impossible. While IVUS may have theoretical advantages over venography in evaluating some of these conditions, there is little data published in the literature on this subject in general and none as it relates to CCSVI or jugular veins. 439 440 441 Echogenicity will be less for intimal hyperplasia than for thrombus lining the vessel wall. Perivenous inflammation may be detectable as separate from the vein itself. 442 443 Use of IVUS for balloon selection (Table 1, Figure 10) 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 Balloon sizing is a great challenge in treating stenoses of the internal jugular veins. Unlike the azygous vein and arteries which have a relatively uniform circular shape, the internal jugular veins do not. They may have a round, oval or multifaceted shape. Venography cannot accurately detect these shapes without the use of multiple views. Moreover, maximum and minimum diameters may be so disparate that simple estimates may grossly underestimate or overestimate the balloon size selection. Because these stenoses usually require large balloons and high pressures, improper sizing may result in serious complications such as dissection, tears and occlusions or inadequate distension and ineffective treatment. 454 455 456 457 458 Analysis by IVUS makes quite clear the deficiencies of venography. The cross sectional anatomy of the vein and the variation of size based on phase of respiration may it clear that cross sectional area (circumference) is the superior criteria for assessing size of the vein and for selecting the appropriate balloon for venoplasty or valvuloplasty. 459 Post intervention assessment 460 461 462 463 464 465 IVUS is helpful in monitoring the treatment. Because many of the intraluminal pathological states are only clearly detectable by IVUS, assessment of the postangioplasty state is best done by IVUS. Incomplete opening of immobile valves and incomplete disruptions of webs and septum are readily detected by IVUS. 466 467 468 469 470 The major complications of treatment of CCSVI are procedural injuries such as lacerations, valvular avulsions, and dissections. They may be difficult to differentiate on venography alone but are easily differentiated on IVUS. Further post-procedural stenosis caused by intimal hyperplasia and in-stent stenosis can be detected and quantified. 471 Summary 472 473 474 475 476 477 Intravascular ultrasound is an essential imaging modality that facilitates detection of the intraluminal pathology associated with CCSVI, including valve abnormalities, webs and septum. It facilitates differentiation of a variety of stenotic lesions. IVUS allows precision in sizing angioplasty balloons and is an excellent method of judging treatment results and complications. It should be considered part of the standard of care. 478 Bibliography 479 1. Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, et al: Chronic cerebrospinal venous 480 insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg 481 Psychiatry 2009; 80: 392-399. 482 2. Zamboni p, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, et al: A prospective open-label study 483 of endovascular treatment of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency. J 484 Vasc Surg 2009; 50: 1348-1358. 485 486 487 3. Zamboni P, Galeotti R: The chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency syndrome. Phlebology 2010; 25: 269-279. 4. Laupacis A, Lillie E, Dueck MD, et al: Association between chronic 488 cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. 489 CMAJ 2011; 183:E1203-12. Epub 2011 Oct 3. 490 5. Huang P, Yang Y, Chen C, et al: Successful Treatment of Cerebral 491 Venous Thrombosis Associated with Bilateral Internal Jugular Vein 492 Stenosis Using Direct Thrombolysis and Stenting: A Case Report. 493 Kaohsiung Journal of Med Sci, 2005; 21:527-531. 494 6. Philips WF, Bagley LJ, M.D., Sinson GP, et al: Endovascular thrombolysis 495 for symptomatic cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurosurgery 1999; 90: 65- 496 71. 497 7. Gurley MB, King TS, Tsai FY: Sigmoid Sinus Thrombosis Associated with 498 Internal Jugular Venous Occlusion: Direct Thrombolytic Treatment. Stroke: 499 1996; 3: 306-14. 500 501 502 8. Hartmann A, Mast H, Stapf C, et al: Peripheral hemodialysis shunt with intracranial venous congestion. Stroke 2001; 32: 2945-2946. 9. Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, et al: Chronic cerebrospinal venous 503 insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg 504 Psychiatry 2009; 80: 392-399. 505 506 507 508 509 10. Lee DL, Eigler N, Luo H, et al: Effect of intracoronary ultrasound on clinical decision making. American Heart Journal 1995; 129: 1084-1093. 11. Lee JT, White RA: Basics of intravascular ultrasound: An essential tool for the endovascular surgeon. Semin Vasc Surg 2004; 17: 110-118. 12. Irshad K, Millar S, Velu R, et al: Virtual Histology Intravascular Ultrasound 510 in Carotid Interventions. Journal of Endovascular Therapy 2007; 14: 198- 511 207. 512 13. Bartel T, Eggebrecht H, Muller S: et al: Comparisons of diagnostic and 513 therapeutic value of transesophageal echocardiography, intravascular 514 ultrasonic imaging, and intraluminal phased-array imaging in aortic 515 dissection with tear in the descending thoracic aorta (type B). Am J 516 Cardiol 2007; 99: 270-4. Epub 2006 Nov 27. 517 14. Koschyk DH, Nienaber CA, Knap M: How to guide stent-graft implantation 518 in Type B aortic dissection? Comparison of angiography, transesophageal 519 echocardiography, and intravascular ultrasound. Circulation 2005; 520 112:1260-4. 521 15. Fussl R, Burkhard-Meier C, Deutsch KS, et al: Dissection following balloon 522 angioplasty: predictive possibilities using pre-interventional intravascular 523 ultrasonography. Z Kardiol 1995; 84:205-215. 524 16. Patel NH, Hahn D, Corness KA: Blunt chest trauma victims: Role of 525 intravascular ultrasound and transesophageal echocardiography in cases 526 of abnormal thoracic aortogram. J Trauma 2003; 55: 330-337. 527 17. Arbab-Zadeh A, Mehta RL, Ziegler TW, et al: Hemodialysis access 528 assessment with intravascular ultrasound. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 4: 813- 529 823. 530 18. Higuchi T, Okuda N, Aoki K, et al: Intravascular ultrasound imaging before 531 and after angioplasty for stenosis of arteriovenous fistulae in 532 haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001 Jan; 16(1):151-5. 533 19. Forauer AR, Gemete JJ, Narasimhan LD, et al: Intravascular ultrasound in 534 the diagnosis and treatment of iliac vein compression (May-Thurner) 535 Syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002; 13:523-7. 536 20. Ahmed HK, Hagspiel KD: Intravascular ultrasonic findings in May-thurner 537 syndrome (iliac vein compression syndrome. J Ultrasound Med 2001; 538 20:251-6. 539 540 541 21. Neglen P, Raju S: Intravascular ultrasound scan evaluation of the obstructed vein. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35:694-700. 22. Diaconu, S. Staugaitis, J. McBride J, et al: Anatomical and histological 542 analysis of venous structures associated with chronic cerebro-spinal 543 venous insufficiency. Abstract presented at ECTRIMS/ACTRIMS 544 Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 21, 2011. 545 23. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R: Embryological background of truncular 546 venous malformation in the extracranial venous pathways as the cause of 547 chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency. Int Angiol 2010; 29:95-108. 548 549 Captions for illustrations 550 551 552 Figure 1. Normal internal jugular IVUS 553 554 555 556 Index: 1. Transverse sinus tributary, possibly posterior cerebral vein or condylar emissary vein. 2. Inferior petrosal vein entering sigmoid sinus; 3. Pharyngeal veins in upper IJV; 4. Facial vein; 5. Superior thyroid veins; 6. Inferior thyroid veins; 7. Confluens of IJV with subclavian vein. 557 558 559 Figure 2: Normal azygous IVUS 560 561 562 Legend: 1. intercostal artery (asterisk) indenting the azygous vein, 2. Intercostal vein; 3. Typical compression of mid-portion of the ascending azygous vein; 4. Spine; 5. Aorta; 6.orifice of accessory hemiazygous vein. 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 Figure 3: Valvular stenosis 570 571 572 573 Figure 3B: Total valvular obstruction: 1. Axial and longitudinal views show a widely patent upper internal jugular vein. There is strong lumen/intimal interface. 2. More inferiorly as the transducer traverses the obstruction, a lumen is not visible on either longitudinal or axial views. 574 575 576 577 578 579 580 Figure 4 Septum IVUS from the transverse sinus (A) to the confluens with the subclavian vein (B). Note compression of the carotid artery of the J2 segment of the IJV (F). IVUS of the azygous vein IVUS from distal ascending portion (A) to junction of the arch with the superior vena cava (F) Figure 3A: Partial valvular stenosis with associated webs: 1. shows 60% stenosis of the IJV at the confluens with the subclavian vein. Contast contour is smooth. 2. The IVUS probe at site of interrogation. 3. There is evidence of echogenic thickening at the edges of this immobile valve (white arrows). This represents the stenosis. The outer wall of the vein (black arrows) is much larger than the area that contains the contrast media Figure 4A: Internal jugular septum: 1. Arrows point to a subtle "jet" of contrast at the confluens. This stenosis was missed by the first angiographer. 2. Axial IVUS shows the septum extending down to the innominate vein confluens (arrows). 3. Longitudinal IVUS reveals the septum dividing the lumen (arrowheads). 4. Angioplasty reveals the area of stenosis. High pressures were required to relieve this stenosis. 581 582 583 584 Figure 4B: Occult Azygous septum: 1.Venography was interpreted as being normal, even in retrospect. Arrow points to the area of abnormality seen on IVUS. 2. Axial IVUS shows intraluminal echogenic tissue (arrows). 3. Longitudinal IVUS clearly demonstrates the intraluminal tissue. 585 586 587 588 589 590 Figure 5: Membrane. 591 592 593 594 595 596 597 Figure 6: Web in Azygous: 598 599 600 601 602 603 Figure 7: Thrombus in dural sinus and IJV: 604 605 606 607 608 Figure 8: Phasic narrowing of azygous vein 609 610 611 612 613 Figure 9: Intimal hyperplasia 614 615 616 Figure 9B: Intimal Hyperplasia within stent: 1. Venography shows occlusion of a stent placed during treatment of CCSVI by another physician. Differentiation of thrombus and intimal hyperplasia cannot be discerned. 2. After first attempt of Membranes are transverse flaps that obstruct flow. They likely represent malformed valve tissue. Venography (A) with the catheter cephalad to the membrane appears normal. With the catheter withdrawn centrally (B), the membrane becomes visible (arrows). It is postulated that the catheter has pushed the membrane open against the lateral wall in Figure 7A. Webs are small tangles of tissue within the lumen of the vein possibly remnants of the cardinal vein maturation into the adult veins. 1. Arrows point to small areas of echogenic material. They may represent webs. However single areas of abnormal thickening of a valve could cause such an appearance. 2. The longitudinal view illustrates that this tissue has the random nature of a web (white circle) rather than of a valve. A. Thrombus fills the lumen and surrounds the transducer (curved arrow) which nearly fills the lumen. The thrombus is displayed as bright mottled echogenic reflections. The venous wall is well seen (straight arrow); in this case it is located within the dural sinus characterized by a triangular shape. B.The brightly echogenic thrombus extends into the internal jugular vein. Venography (not shown) revealed a long tapered narrowing of the ascending part of the azygous vein. IVUS, performed in both expiration and inspiration, clearly shows the phasic nature of this stenosis. No benefit will be derived from venoplasty because IVUS has demonstrated that this is not a fixed stenosis. Figure 9A: Intimal hyperplasia after thrombosis recanalization: 1. It is difficult to see the stenosis on this axial image because of the lack of echogenicity of the cause. 2. The longitudinal view shows this to great advantage. Arrows point to the edge of intimal which is markedly thickened. 617 618 619 suction aspiration, axial IVUS differentiates echogenic stent (black arrow) from echolucent intimal hyperplasia (white arrow) from echogenic thrombus (dotted arrow). 620 621 622 623 624 625 626 627 628 629 630 Figure 10: Using IVUS for treatment planning 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 638 Figure 10B: Quantifying stenosis: 1. Venography illustrates overdilation of the IJV during procedure done by a prior proceduralist. This stenosis was mostly likely caused by angioplasty of the incorrect segment or restenosis. 2. Curved echo represents wall of stenosed valves without remainder of vein excluded from direct flow. 3. Cross sectional measurement of both inner stenotic lumen and outer edge of wall, allows accurate calculation of percentage stenosis of 61.7% as opposed to values derived from diameter measurements ranging from 13% to 52%. Figure 10A: Assessing vein size before angioplasty: This axial IVUS illustrates some of the difficulty in assessing dimensions of veins and in choosing the proper balloon for safe and effective treatment of stenoses. Depending on orientations of the central ray of the fluoroscope and the vein axis, widely discrepant estimations of size may occur. The shortest diameter is less that 6 millimeters and the longest diameter is greater than 11 millimeters. Too small a balloon may be ineffective or result in short term clinical response. Too large a balloon may overdistend and injure the vein, thus increasing risk of stenosis or tear of the vein wall. Seeking a balloon 50% greater in size than this vein would indicate a balloon with CSA of about 100 mm2. A ...mm balloon was chosen. 639 640 Table 1 Angioplasty balloon cross sectional area Balloon Diameter (mm) CSA (mm2) Balloon Diameter (mm) CSA (mm2) 5 2 12 113 6 28 14 154 7 38 16 201 8 50 18 254 9 63 20 314 10 79 22 380