Overview of Collaborative Child Welfare

advertisement

Child Welfare in Ontario:

Developing a Collaborative Intervention Model

Consultation Draft

A Position Paper submitted by the

Provincial Project Committee on

Enhancing Positive Worker Interventions

With Children and their Families in Protection

Services: Best Practices and Required Skills

Editor

Gary C. Dumbrill

Committee Members and Contributing Authors

Anne Bester, Ariel Burns, Susan Carmichael, Gerald de Montigny, Gary C. Dumbrill, David Gill,

Rhonda Hallberg, Phil Howe, Kim Martin, Bea Kemp, Andrew Koster (Project Manager), Rick Lang,

Paula Loube, Phyllis Lovell, Nancy Macdonald, Nancy MacGillivray, Greg Moon, Michael Mulroney,

Darlene Niemi, Mike O’Brien, Rocci Pagnello, Juanita Parent, Janice Robinson, Jolan Rimnyak,

David Rivard (Project Champion), Marilyn Sinclair, Bernard Smith, Susan Verrill, Lori Watts,

Guest Authors & Presenters

(In order of appearance or submission)

Bruce Leslie, Peter Dudding, George Savoury, Elizabeth French, Judith Finlay (Assisted by a Youth

Coordinator, and four Youth in Care), Katharine Dill, Michael Ansu, Emmanuelle Antwi, Greta Liupakka,

Judith Wong, Sarah Maiter, Bruce Burbank, Rocco Gizzarelli, Raymond Lemay,

June Ying Yee, Bill Lee,

Liaison with Other Child Welfare Initiatives

Rocco Gizzarelli, Deborah Goodman, Rhonda Hallberg, Anna Mazurkiewicz, Sandy Moshenko,

Allison Scott, Louise Leck

Support & Auxiliary Functions

Paula Loube, Winnie Lo

This paper and the child welfare model it develops remains the intellectual property of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid

Societies, the paper editor and the Project Committee members. This project was significantly enhanced through the contributions of

faculty from various Schools of Social Work in Ontario and non-sector presenters. Where a named author has contributed sections of

this paper that author retains the copyright of those contributed parts. This paper (and the ideas contained within) may be freely

copied and reproduced in its entirety as long as the original author and copyright information is retained.

T o r o n t o - J u ly 2005

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................. 2

LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 6

Introduction................................................................................................................. 6

Background ................................................................................................................. 6

Recommendation ......................................................................................................... 7

The Need for Transformation ..................................................................................... 9

Conclusion Steps ....................................................................................................... 14

Questions for Feedback: ........................................................................................... 15

SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 16

Project Mandate........................................................................................................ 16

List of Participants.................................................................................................... 16

Phases of the Project ................................................................................................ 20

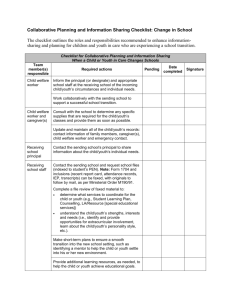

Overview of Collaborative Child Welfare: A Model for Ontario ............................ 21

SECTION 2: A COLLABORATIVE INTERVENTION MODEL ........................... 26

Introduction............................................................................................................... 26

A Historical Perspective on Collaborative Casework .............................................. 31

Collaboration: A Theoretical Framework for the Client-Worker Relationship ....... 34

What Parents Bring to Collaboration ....................................................................... 37

What Youth Bring to Collaboration .......................................................................... 41

What Workers Bring to Collaboration ...................................................................... 45

What Supervisors Bring to Collaboration ................................................................ 50

What Workers, Children, and Families Need To Do Together to Improve

Collaboration ............................................................................................................ 53

Can Workers Build Partnerships with Parents When Litigation is Involved? ......... 57

Authority and Collaboration ..................................................................................... 59

Summary of Collaboration ........................................................................................ 62

Recommendations Section 2: Collaborative Intervention Model ............................ 63

SECTION 3: DEVELOPING COLLABORATIVE ORGANIZATIONS ................ 66

The Role of Governance and Leadership in the Emerging Field of Child Welfare .. 66

Developing Outcomes That Measure the Effectiveness of Child Welfare Service

Delivery ..................................................................................................................... 70

Incorporating Agency Awareness of Aboriginal Child Welfare Issues .................... 86

The Ethics of Child Protection Services for People From Diverse Ethno-Racial

Backgrounds ............................................................................................................. 88

Towards Improving Child Welfare Services to Adolescents ..................................... 90

Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 92

Advocacy for Social Justice ...................................................................................... 94

The Need for an Increased Acceptance of Feminist Practice Within Child Welfare 97

2

Anti-Oppressive Practice ........................................................................................ 101

Social Inclusion ....................................................................................................... 104

The Influences of an Agency Code of Conduct and Social Work Code of Ethics ... 106

Conclusion Regarding Collaborative Organizations ............................................. 108

Recommendations for Section 3: Developing Collaborative Organizations ......... 108

SECTION 4: DEVELOPING COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE ............................ 111

Introduction............................................................................................................. 111

Surveys of Worker and Manager Responses to the Issues Raised By The Position

Paper On Enhancing Client-Worker Relationships and Collaboration: The Attached

Manual .................................................................................................................... 112

Enhancing Worker/Client Relationships................................................................. 112

The Provision of Child Welfare Services to Native Children, Families and

Communities ........................................................................................................... 114

Focus Group Minutes.............................................................................................. 114

Recommendations ................................................................................................... 116

SECTION 5: THEORY TO AID COLLABORATION ........................................... 119

Attachment, Separation and Loss ........................................................................... 120

A Theoretical Framework for Working with Adolescents....................................... 125

Ethno-Cultural Families and Children ................................................................... 133

Working with the Community and Child Welfare ................................................... 139

Collaborative Work With Foster Parents ............................................................... 143

Trauma Counselling................................................................................................ 145

Crisis Intervention Model ....................................................................................... 146

Narrative Therapy ................................................................................................... 147

Brief Therapy .......................................................................................................... 148

Reality Therapy (Choice Theory)............................................................................ 149

Family Theory ......................................................................................................... 152

Family Systems Theory ........................................................................................... 153

Behaviour Therapy.................................................................................................. 155

Ecological Theory ................................................................................................... 157

SECTION 6: RECOMMENDATIONS TO ENHANCE THE SYSTEM FOR

POSITIVE CLIENT OUTCOMES ............................................................................. 160

ORAM and Present Casework Recording Situation ............................................... 160

Improving Child Protection Assessment in Ontario ............................................... 167

Criteria for Choosing a Needs Assessment ............................................................. 171

Challenges Involved With Forming Child Welfare Service Plans .......................... 174

Recording and the Issue of Social Inclusion ........................................................... 174

Coordination of This Project With Differential Response ...................................... 175

The Kinship Model of Service and Collaboration .................................................. 177

Looking After Children (LAC), Resilience and Collaboration ............................... 179

Family Group Conferencing and Collaboration .................................................... 183

Clinical Supervision in a Child Welfare Context .................................................... 186

SECTION 7: IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES ............................................... 201

3

Overview of the Purpose ......................................................................................... 201

The Main Goals of the Intervention Model for Ontario. ........................................ 202

Support to the Secretariat’s Transformation Initiatives ......................................... 202

Support to Other OACAS Initiatives, Programs, and Projects ............................... 204

Where to Go From Here? ....................................................................................... 208

Questions for Feedback: ......................................................................................... 209

APPENDIX 1: THE PROJECT .................................................................................. 237

Purpose of the Project ............................................................................................ 237

Description of the Project ....................................................................................... 237

Project Outcomes .................................................................................................... 239

Coordination with Related OACAS Projects .......................................................... 239

APPENDIX 2: PROJECT WORK PLAN .................................................................. 239

APPENDIX 3: FOCUS GROUP PARTICIPATION ................................................ 241

APPENDIX 4: OFFICE OF CHILD AND FAMILY SERVICE ADVOCACY,

PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE ................................................................................. 244

PRINCIPLES ................................................................................................................ 244

APPENDIX 5: A SAMPLE OUTLINE OF AN ADVOCACY/POLICY

COMMITTEE ............................................................................................................... 248

APPENDIX 6: A SAMPLE MISSION STATEMENT AND THE RELATED

PERFORMANCE OUTCOMES FROM ALGOMA CHILDREN’S AID SOCIETY

......................................................................................................................................... 255

APPENDIX 7: NOTES FROM THE YOUTH FORUM.......................................... 261

APPENDIX 8: PROFESSIONAL CODES OF ETHICS FOR WORKERS........... 265

APPENDIX 9: RELATIONSHIP-GROUNDED, SAFETY ORGANIZED CHILD

PROTECTION PRACTICE: DREAMTIME OR REAL-TIME OPTION FOR

CHILD WELFARE? .................................................................................................. 269

APPENDIX 10: ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ON CRISIS INTERVENTION

......................................................................................................................................... 282

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE 1: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR A PENDULUM SWING TOWARDS THE MIDDLE WHILE

STILL ENSURING CHILD SAFETY ................................................................................ 27

FIGURE 2: THE IMPORTANCE OF CLIENT COLLABORATION IN COMBINATION WITH OTHER

STRATEGIES FOR PROTECTING CHILDREN .................................................................. 31

FIGURE 3: PAPERWORK - PEOPLEWORK BY OPSEU/SEFPO ............................................. 33

FIGURE 4: ACCOUNTABILITY BY OPSEU/SEFPO.............................................................. 46

FIGURE 5: ROOT CAUSE ANALYSIS .................................................................................... 48

FIGURE 6: COMPARING MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS WITH HERTZBERG’S SATISFIERS

................................................................................................................................... 52

FIGURE 7: THE HOPES AND FEARS OF PARENTS AND WORKERS ........................................ 53

4

FIGURE 8: COLLABORATIVE PLANNING ............................................................................. 54

FIGURE 9: THE STEPS OF CHANGE FOR PARENTS ............................................................... 57

FIGURE 10: RESTRAINING AND DRIVING FORCES AND THEIR IMPACT ON A LEARNING

CULTURE ................................................................................................................... 66

FIGURE 11: OUTCOMES #1 ................................................................................................. 72

FIGURE 12: OUTCOMES #2 ................................................................................................ 73

FIGURE 13: OUTCOMES AND CLIENT ENGAGEMENT USING THE OACAS EXCELLENT

SYSTEM MODEL ......................................................................................................... 81

FIGURE 14: COLLABORATIVE OR COERCIVE RELATIONSHIPS IN CHILD WELFARE ........... 111

FIGURE 15: ELEMENTS OF COMMUNITY ........................................................................... 141

FIGURE 16: CRISIS WINDOW FOR CHANGE....................................................................... 193

FIGURE 17A: BUILDING COVEY’S QUADRANT 2 FOCUS ................................................... 194

FIGURE 18: MOTIVATION, MASLOW, AND CLIENT ENGAGEMENT .................................... 197

FIGURE 19 CRISIS INTERVENTION MODEL ....................................................................... 285

*It is recommended that the pages for the list of figures be duplicated separately on a

colour printer and then used to replace black and white photocopies.

Please Note:

The Manual entitled Surveys of Worker and Manager Responses to the Issues Raised By

The Position Paper On Enhancing Client-Worker Relationships and Collaboration (July

2005) is considered part of this Position Paper and can be found in electronic format on

the accompanying CD. The CD also includes many of the references and the PowerPoint

presentations used in development of this project. It also introduces the viewer/reader to

the Project itself. Robert Price, an I.T. coordinator at the Brant CAS designed the CD.

Acknowledgements

A number of individual committee members and others in the field developed topics in

this Position Paper. As a result, their important contributions are recognized individually.

However, many parts of this paper are the culmination of many hours of group discussion

and written submissions by all 30 committee members. One of our members, Paula

Loube, kept detailed minutes of the group discussions at the monthly two-day meetings to

ensure that valuable ideas and perspectives from individual members were retained.

At the OACAS, we wish to thank Sheela Sharma and Jill Evertman for sustaining us with

food and drinks, especially when our discussions were lively; April Salmon for always

making photocopies at a moment’s notice; and Doug Snyder for helping us out with our

computers and power point presentations.

5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

This paper develops a collaborative child welfare model for Ontario. By “collaborative

child welfare” we mean a system in which child protection agencies use casework and

community development skills to engage parents and communities in the protection of

children. We recommend this model be adopted by Ontario Children’s Aid Societies and

used as the basis for transforming the delivery of child protection services within the

province.

Background

This paper has been produced by a committee mandated by the Local Directors Section

and Zone Chairs for Ontario Children’s Aid Societies to examine and recommend

improvements to child welfare practice within the province. As the committee began its

work it became apparent that it would be beneficial to have a link to the Child Welfare

Secretariat of the Ministry of Community and Youth Services that was developing a

policy framework for the transformation of child welfare in Ontario. Consequently a

liaison from the Secretariat joined the committee. Over time it expanded its membership

and was eventually comprised of agency Directors, managers, front line staff, a number

of academics, representatives from the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies,

as well as representatives from the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services.

The committee began by seeking to improve individual casework. It became evident,

however, that intervention on a micro level was inextricably linked to macro issues such

as agency culture, government initiatives, and the relationship agencies had with their

communities. As a result, the committee examined the entire Ontario child welfare

system and the societal and policy contexts that define the way it operates. The

committee took an evidence-based approach with the direction based on:

o A review of literature and research on best practices in child welfare

o Presentations to the committee by experts in specific areas of child welfare policy

and practice

o Results from a province wide survey undertaken by the committee of workers and

supervisors views about the best ways to serve families and protect children

The findings from this work provide the basis for our recommending a policy and

practice shift in Ontario toward the “collaborative model” outlined in this paper. The

committee also ensured, through liaison with other provincial committees and the

Ministry of Children and Youth Services that recommendations contained in this paper

complement other provincial child welfare initiatives. Consequently, we suggest that the

model presented in this paper not only be adopted by Children’s Aid Societies, but that it

also be drawn upon to guide and underpin the strategic directions being taken in current

child welfare transformation initiatives.

6

Recommendation

The committee developed a “collaborative child welfare model” which we believe will

benefit and improve child protection services to children and their families in Ontario.

Developing a model is not an uncommon exercise for jurisdictions that are re-evaluating

their child welfare services. Jurisdictions in Australia and the United States have

developed local models. The committee looked at several of these models, particularly

those in Minnesota and North Carolina and also a model developed in Australia by

Andrew Turnell, based on his book ‘Signs of Safety’ (Turnell & Edwards, 1999). We

have included concepts from these models in this Position Paper but ultimately we

recognized that Ontario required its own model. The province is unique in geography

and in the societal, cultural and economic diversity existing within the region. Also, the

province’s child welfare system is operated at local levels through Children’s Aid

Societies managed by their own independent Boards and management teams who are

aware of the child welfare needs and challenges in their own communities. The model

we have developed is designed as an overarching province-wide approach to

“collaborative service” delivery that is refined and tailored to meet local community

needs by each agency.

Collaboration in our model operates at intersecting levels. Of course, in child welfare,

collaboration with parents1 is not always possible, yet the committee found extensive

evidence that where collaboration is possible, this is the most effective means of ensuring

child safety. The collaboration we suggest, however, is not simply at worker-parent level.

We suggest a shift in the ways protecting children is conceptualized and delivered - a

shift away from seeing child protection as intervention as simply a micro service

delivered by a Children’s Aid Society and a shift toward seeing it as a community

response coordinated by a Children’s Aid Society.

Ideally, at the heart of intervention, a parent will collaborate with a Children’s Aid

worker to address child protection concerns. Supporting this worker-parent relationship

will be collaboration at broader levels between the worker and community

agencies/resources that ensure a parent can access help to appropriately care for their

children. In instances where worker-parent collaboration is not possible, the worker will

implement a protection plan independent of the parent but this will not be independent

from the collaboration and support of the broader community. Under this model a

Children’s Aid Society coordinates child protection but it is the concern and

responsibility of the entire community. This model not only calls for workers to develop

collaborative relationships with parents to help enhance their capacity to protect and care

for their children, but also calls for workers to develop collaborative relationships with

communities to help enhance its capacity to protect and care for children. As such the

model conceptualizes child protection as everybody’s responsibility in a similar way to

the vision captured in the proverb, “it takes a village to raise a child.” In Africa where

this proverb originates, a “high context” (Hall, 1976) culture and community collectively

(Battle, 1997) ensures that people understand that the dynamic behind a village raising

We use the term “parent” through this Position Paper to refer to a child’s primary caregivers and we

recognize that such “parents” may be a step-parent, grandparent, older sibling or any other adult who is a

primary caregiver for a child.

1

7

children is the collaboration inherent in a village community. This meaning can be lost in

individualistic western societies and consequently to understand the proverb, we

emphasize that, “it takes a village ‘that collaborates’ to raise a child.”

The efficacy and need for a collaborative model is supported by literature and research.

Our model is based on:

o Evidence that children are best protected when workers and parents collaborate

toward promoting child welfare (Farmer & Owen, 1995; J Thoburn, 1992; Trotter,

2002, 2004)

o Evidence that workers must collaborate with children and youth when delivering

child protection intervention (Finlay & Snow, 1998)

o Evidence that supervisors and managers must be a part of the collaborative

process (Bloom-Cooper, 1985; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988b,

1991; Finlay & Snow, 1998; Home Office, Department of Health, Department of

Education and Science, & Welsh Office, 1991)

o Evidence that inter-agency collaboration is crucial to protecting children (BloomCooper, 1985; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988b, 1991; Finlay &

Snow, 1998; Home Office et al., 1991)

o Evidence that whole communities need to work together in protecting children

(Bloom-Cooper, 1985; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988b, 1991;

Finlay & Snow, 1998; Home Office et al., 1991)

o Evidence that government and policy makers must move beyond making

reactionary pendulum swings in child welfare policy and practice (Reder, Duncan,

& Gray, 1993)

o Evidence that academic researchers and practitioners need to collaborate to

measure intervention outcomes and identify best practice (Leslie, 2005; Trocmé,

2005; Vandermeulen, Wekerle, & Ylagan, 2005; VanWilgenburg, 2005)

Because collaboration is involved in all the above, the elements of our model are not

new, but combining of them into a “collaborative child welfare model” is new. We

suggest that this model become the foundation on which the transformation of the

Ontario child welfare be based.

We envision our model being implemented in different ways across the province.

Tailoring this model for each community is crucial because communities such as

Attawapaskat, Toronto and Timmins are distinct; the 143 different First Nations within

the province each differ, and Ontario’s various immigrant and ethno-racial communities

have diverse needs. To be viable a model has to meet the unique strengths, needs and

resources within these diverse communities. The Ontario system can respond to these

differing needs because the child protection system is governed by 53 child welfare

agencies comprised of local community members who can ensure that each agency

responds and collaborates with its constituents in the most appropriate manner. Our

collaborative model is designed for implementation by agencies that are a part of these

local communities and are aware of their local needs.

8

We recommend that the Children’s Aid Societies in Ontario consider the merits of the

model presented in this paper and adopt the recommendations of this report. The report

is submitted as a ‘consultation’ draft designed to elicit feedback and discussion. This was

also done with the knowledge that the discussion will produce some of the changes that

the Committee believes need to occur to support the Transformation Agenda of the

Secretariat of the Ministry of Children and Youth.

The Need for Transformation

The Ontario child welfare reforms of the late 1990s and early 2000s brought:

o A reminder that child safety must always be paramount

o System enhancement that ensures workers pay attention to safety issues and are

accountable for doing so

o Increased supervisory involvement in case decisions

o Training that ensures staff have knowledge about pathology and indicators related

to the abuse and/or neglect of children

o Higher forensic investigation standards

o Staff who scrutinize the effectiveness of their interventions and do not personalize

the need for their clients to be successful

o An awareness that some forms of worker-parent relationship can be ineffectual

and in fact increase the possibility of abuse

o Better documentation and record keeping systems

These reforms increased the capacity of the Ontario child welfare system to investigate

and intervene in families where child abuse and neglect was occurring, or was suspected

to be occurring, or where it was thought likely to occur in the future. However, the

reforms also inadvertently compromised the ability of agencies to deliver social work

services that protect children in their own communities and homes. A focus on forensic

investigation and regulating parents reduced the system’s capacity to use social work

methods that bring child protection changes in families and communities. Indeed, this

shift has been so substantial that some now see social work intervention and the

development of a casework relationship with parents as an inessential part of child

protection practice. The shift toward investigating and regulating families and an

increased emphasis on liability and a fear of error resulted in an increase of children

being removed from their homes as a protection strategy. This resulted in a 63% increase

of children in care from 1998 to 2004. As budgets are affected by expenditures for

children in care, as well as associated legal costs and additional staff, the annual cost of

delivering child protection services in Ontario increased by 115% from $542 million in

1998 to $1.16 billion in 2004.

The increased ability of the Ontario system to remove children from their homes is not

entirely problematic, but the decreased ability to protect children in their own homes is a

problem that must be remedied. Consequently the Collaborative Child Welfare Model

we propose retains the gains of reform and maintains child safety as the primary focus of

intervention, yet it balances the investigation and regulation of families by providing an

opportunity for parents and their communities to engage with efforts that reduce the risk

9

to children. The need to balance the Ontario system is not just fiscal, but it is also

required in order to protect children properly. Evidence suggests that workers who

confront parents with child protection concerns in the absence of a strong worker-client

relationship are unlikely to bring about protective changes (Trotter, 2004). The proven

characteristics of a worker-parent relationship that is capable of protecting children is

well established:

The research in child protection and in work with other involuntary clients

suggests that the use of certain skills by child protection workers is likely to be

related to positive client outcomes. In particular, effective practice involves:

helping clients and client families to understand the role of the child protection

worker; working through a problem-solving process which focuses on the client’s

rather than the worker’s definitions of problems; reinforcing the client’s prosocial expression and actions; making appropriate use of confrontation; and using

these skills within a collaborative client/worker relationship. (Trotter, 2002, p. 38)

Research consistently points to better outcomes for children when workers and parents

collaborate (Callahan, Field, Hubberstey, & Wharf, 1998; Cleaver & Freeman, 1995;

Trotter, 2002, 2004). Some researchers suggest that a worker or child protection system

that lacks the capacity to develop such relationships ultimately fails to protect children

(Trotter, 2004). In other words, children are better protected where workers balance

investigatory and helping practices.

The Policy and Practice Pendulum

It is no surprise that the Ontario system needs balancing. An internationally recognised

phenomenon in child welfare policy and practice has been the pendulum swing between

family preservation and child safety (Editorial, 1996; Finholm, 1996; Gardner, 1996;

McLarin, 1995; Paterson, 1999; Reder et al., 1993; Seebach, 2000; Watson, 1997). When

the pendulum is fully extended toward family preservation, working “with” families and

maintaining children in their own homes takes precedence over child safety. Work in this

phase is marked by a reticence to remove children from their homes and avoidable child

deaths result. Public outcry over child deaths (Bloom-Cooper, 1985; Coyle, 2001;

Gelles, 1996; Gove, 1995; Ontario Association of Children's Aid Societies & The Office

of the Chief Coroner of Ontario, 1997; Sanders, Colton, & Roberts, 1999; Tesher, 2001)

creates a momentum that pushes the direction of child safety and eventually this focus on

safety narrows to the extent that intervention becomes inquisitorial. Afraid of making

fatal errors, agencies are quick to remove children from families rather than engage in

casework intervention to reduce risk. In this position the practice principle used is a

cavalier application of the rule, “when in doubt take them out” (Finholm, 1996, p. A1).

An inquisitorial system eventually fails, whether due to increased numbers of children in

care (Gardner, 1996), or due to the eventual inquests into the intrusive ways child

protection workers use authority (Brindle, 1995a, 1995b; Cleaver & Freeman, 1995;

Clyde, 1992; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988a; Home Office,

Department of Health, Department of Education and Science, & Welsh Office, 1988;

Martin, 2005). With such failures the pendulum is pushed back in the opposite direction

and the cycle begins again.

10

Centring the Pendulum: A Collaborative Model

The pendulum moves back and forth because it is driven by reactions to fiscal or public

opinion crises. Seeking a “quick fix,” simplistic solutions to complex problems are

formulated with both policy makers and practitioners shying away from the type of

practice that caused the last crisis to arise. Such reactive responses formulate the entire

mode of intervention leading to the crisis as erroneous (e.g. family preservation or child

removal) rather than seeing its application in a given case as erroneous. Such

oversimplification is akin to mandating angioplasty and prohibiting heart bypass surgery

when cardiologists make errors of being too intrusive and later mandating heart bypass

surgery and prohibiting angioplasty when it becomes obvious that in some cases surgical

intrusion is needed. Society would never accept a medical system designed in this manner

and should not be expected to accept a child welfare system designed in this manner. The

key to a balanced and effective child welfare system is not to swing back and forth

between delivering intrusive or non-intrusive intervention, but to match intervention to

the specific needs of each child and family. We suggest this matching can be achieved

through the collaborative model we develop in this paper. Turnell and Edwards point out

that:

The challenge is to create a structure and models of child protection practice that

address the seriousness of alleged or substantiated maltreatment while

maximizing the possibility of collaboration between families and workers.

(Turnell & Edwards, 1999, p. 27)

We need a structure in which families can collaborate with workers. Such a structure will

increase the likelihood of an accurate assessment being completed and the right

intervention being delivered. In instances where collaboration is contraindicated because

parents are unwilling to cooperate of the nature and level of risk are too high, the broader

collaborative components of this model we have developed will assist the worker in

developing a protection plan. Collaboration characterized by kinship care networks,

relationships with the child’s religious, racial or ethnic communities, relationships with

schools, mental health agencies and other community resources, will help the child

protection worker tailor a to each child’s needs. In this manner, the “village” contributes

to a plan for the child.

Embedding of child protection in multiple layers of collaboration will help policy

makers, practitioners, and communities, understand and respond to the complexities

involved in child protection practice. In such an environment when errors occur, the

likelihood of simplistic solutions being imposed on complex problems will be reduced,

and the system will be much more likely to fine-tune its response and increase its ability

to ensure that the correct intervention is delivered to the correct need.

We suggest, therefore, that to break the oscillations between family preservation and

child safety, all participants in the system must join together in collaboration to create a

balance that maintains the pendulum in the centre. Balance is best created through the

adoption of a system of collaboration where workers and parents co-operate to support

the best interests of children thereby reducing child abuse and neglect. Increasing child

11

safety is the primary objective and collaboration is promoted as an effective means for

achieving this end. We do not propose forms of collaboration that might jeopardise child

safety; rather we propose forms of collaboration that work as effective tools for

promoting child safety. Indeed, if parents are unwilling or unable to collaborate (as

many are), workers must swiftly and unilaterally act to protect children. If abuse is so

serious that collaboration is contraindicated, or if parents reject the opportunity to engage

in a collaborative process, the worker must use intrusive strategies. Yet along side such

intrusion there must be both the capacity and the potential to use casework intervention to

engage parents in a productive change processes. What is required of workers, therefore,

is a balancing of practice characteristics from both ends of the pendulum swing. This

balancing is a complex process because throughout the intervention process the worker

needs to be constantly assessing risk to the child, parental capacity for change, and the

ways the parent is engaging with intervention. Simultaneously the worker also needs to

match their assessment of risk, parental capacity for change and engagement with

corresponding shifts between collaboration to authoritative control as required. As well,

the worker needs to assess and address “risks” in the community such as a lack of

resources that hinder a family’s ability to parent adequately. Although a complex

process, any intervention strategy that does not include these elements will fail to provide

children with the protection and support they deserve.

Although worker-parent collaboration is at the heart of the model, collaboration is

essential at all other levels. Indeed, whatever exchange occurs between workers and

parents is not limited by what they bring to their micro engagement as individuals. It is

also determined by broader agency, policy and societal contexts. For workers to engage

parents in collaborative strategies that protect children it requires not only parents and

workers to work toward these ends, but supervisors, managers, Boards of Directors and

the provincial government. The client-worker relationship is the central element of our

model, but that element can only operate if the operating systems surrounding collaborate

to make it so.

More by opportunity and by design, the concept of collaboration seems to underpin many

of the changes already occurring in the Ontario child welfare system. In addition, many

of the forthcoming changes shift the Ontario system in a direction needed for our model

to be implemented. These changes include:

o A new clinical supervision module is being developed by the Ontario Association

of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS) with the endorsement of the Secretariat of

the Ministry of Children and Youth. This module maintains the paramount

importance of child safety but provides knowledge and skills required for

collaborative intervention.

o It is estimated that presently workers spend upwards of 70% of their time on

paper work and 30% on direct practice. This ratio needs to be reversed with 30%

spent on paperwork and 70% in direct practice.

o It is recognized by the Secretariat of the Ministry of Children and Youth that

workers need to have more time to spend with their clients and supervisors need

12

to have more time for meaningful clinical supervision with their front-line

workers.

o Efforts are already underway by various, autonomous groups who are attempting

to improve recording, strength based assessments, risk assessments and goal

planning that supports child safety and collaborative efforts by front line staff.

These groups include staff from Children’s Aid Societies who are attempting to

improve the Lotus Notes IFERS recording package on an ongoing basis; the

‘Single Information System’ project; child welfare professionals seconded to the

Ministry’s Secretariat; and members of this Paper’s assessment subcommittee.

o There is expanded collaboration between the OACAS and the Secretariat in terms

of co-coordinating efforts in best practices and implementation of new initiatives.

o Several child welfare agencies in Ontario have already initiated changes in board

governance in order to model collaboration. Others have begun to engage in Anti

Oppressive initiatives.

In addition to the initiatives mentioned above, there was a conscious attempt by this

committee to re-establish philosophical and collaborative links with Ontario Schools of

Social Work so they will be teaching students similar philosophies and best practices to

the child welfare agencies that may wish to employ them when they graduate. In

addition, the paper reviewed the Code of Ethics of Social Work and social work views on

relationship. It was hoped that through this involvement, there could be better

recruitment and retention of staff. It was hoped that clarification in this area would also

satisfy the aspirations of current child protection workers and supervisors who still wish

to develop collaborative skills and the appropriate use of the social work relationship in

child welfare services. This consistent approach could have the potential to limit the

movement to ‘helping’ agencies, which has occurred during Child Welfare Reform.

For collaboration to work, agency training has to change. Therefore, the committee has

added sections on training and best practice. Much of the new workers training did not

include the collaborative principles that this paper calls for and clinical supervision itself

took on a more constricted role. This Position Paper attempts to produce that balance

now that government initiatives also require a renewed training emphasis on

collaboration and additional best practice skills for those engaged in the new efforts on

‘collaboration. In fact this paper is written not only as a Position Paper but it follows a

format which could form the basis of a training module on how agencies, supervisors and

workers can develop an understanding of what collaboration actually means and how it

may be achieved. Without this knowledge, both collaboration and the new Initiatives of

the Secretariat will not be achieved.

If the child welfare pendulum is to be centered and children provided with the best

possible protection, the collaboration mentioned above needs to be expanded and

harnessed. The model presented in this Position Paper provides evidence that such

collaboration best serves children and it also provides an ideological and practice basis

from which such collaboration can occur.

13

Conclusion Steps

This draft consultation version of the Position Paper is being distributed to all CAS

agencies and the OACAS for input. The paper is being dispersed on CD that includes all

possible sources of information including Power Point presentations that were provided

to the committee; a compilation of a survey on best practices that was sent out to agencies

with members on the committee; and an extensive reference library to which all members

contributed various articles and several of the references papers. The report package has

been distributed in this manner to help member agencies understand the depth of what

has gone into the draft report to date. It is hoped that when it is received at each agency

that the three copies of the CD will be distributed and copied as needed in order to

provide internal discussion of the various concepts included and recommended within the

draft consultation paper.

The committee discovered that the process of discussing the need for transforming child

welfare in Ontario became an instrument for change in its own right. We developed:

o A growing awareness of what we believe this field needs to do to maintain and

replenish core values of our profession that we believe are ultimately required to

keep children safe, to help families and to strengthen communities

o A greater understanding of what is required for the successful implementation of

kinship care, differential response, and alternatives to court

o An appreciation that solutions are not simple but will only be accomplished

through a comprehensive strategy for collaboration based on appropriate training

for staff; freeing up time for direct service provision by workers; supportive

agency culture; and concrete efforts to link child welfare with ‘community’ in its

various forms

o A realization that the field of child welfare in Ontario should define its own core

values and not leave that to government

o An understanding that in many instances each diverse community should define,

to some degree, its own most effective community system for implementing

provincial standards for ensuring child safety

We hope that this consultation process will stimulate discussion of these issues in each

agency and will precipitate a similar dialogue so that each agency will come to its own

conclusion about the ways the model presented in this paper can be beneficial to its work.

In this consultation we ask that each CAS agency and/or Aboriginal Child Welfare

Agency provide written comments to the Project Committee by August 10th, 2005. The

ideas that are provided back will enhance the final product. The committee has drafted

some questions in order to assist the responses. Any responses positive or negative will

be received and discussed at the August 17th meeting of the committee. Any related

material that agencies may have found helpful in attempting to accomplish the same

recommendations would also be well received and possibly added to the report as a

potential resource.

14

Changes will be incorporated and then the final report will be presented to the Zone

Chairs and to the scheduled Consultation in September for the endorsement by the field

itself.

Questions for Feedback:

1. Is this proposed collaborative intervention model beneficial to child welfare

agencies in Ontario at this time? If so why? If not, why not?

2. Child Welfare Reform emphasized child safety. Even though this report has

emphasized that child safety is still the paramount concern of a child welfare

agency, does you agency have any advice on how child safety can be further

enhanced within a collaborative Intervention Model in ways that has as yet been

sufficiently articulated in this draft report?

3. Are their any points in this Project Paper with which you disagree?

4. This Project Paper connects appropriate agency culture to successful

‘collaboration’ at a front-line and supervisory level. Does the agency have any

comments?

5. Specific skill sets and theoretical frameworks have been offered as important

ingredients for front line workers and supervisors? Does the agency have any

comments?

6. Are there any additional areas that believe should be covered in a comprehensive

model for child welfare intervention?

7. What would be the biggest challenges to overcome in terms of an agency

incorporating this Intervention Model in light of the new Transformation Agenda

of the Secretariat?

8. Does your agency believe that an articulated model of intervention such as this

will assist in improved collaboration with children, their families, and their

communities?

9. Some Children’s Aid Societies have already combined with mental health and

family counseling agencies in their communities. Will this report help efforts for

internal cohesion of vision, mission, and staff attitudes to service delivery?

10. Additional comments?

Please note: Agencies may decide to send one response or allow individual respondents

to send in responses directly to the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies.

15

SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION

Project Mandate

In 2004, the Local Directors Section and Zone Chairs for Ontario Children’s Aid

Societies approved a provincial project to examine and recommend improvements to

child welfare practice within the province. The need for this project emerged from a

recognition that the Ontario child welfare system needed to be transformed.

This committee’s work is now complete and we recommend a child welfare policy and

practice shift in Ontario toward what we have called a “collaborative intervention

model.” In this Position Paper we will show evidence that children are better protected

when child protection agencies work in partnership and “collaboration” with families as

well as communities. Use of a collaborative model does not prohibit child protection

agencies from acting independently and unilaterally to protect children when needed - in

fact the ability to do so remains essential in child protection work. The model involves,

however, child protection agencies and workers utilizing, wherever possible, social work

skills to engage families and communities into collaborative intervention processes

focused on the safety and well being of children.

List of Participants

Project Team Members

Anne Bester, Director of Services,

Bruce Children’s Aid Society

(519) 881-1822

Ariel Burns, Social Worker,

The Children’s Aid Society of Ottawa

(613) 747-7800

Susan Carmichael, Director of Services,

The Children’s Aid Society of Simcoe County

(705) 726-6587

Gerald de Montigny, Associate Professor,

Faculty of Social Work, Carleton University

(613) 520-2600 ext. 3658

Gary C. Dumbrill, Assistant Professor and Chair of

Undergraduate Studies, Faculty of Social Work,

McMaster University

(905) 525-9140

David Gill, First Response Supervisor,

Niagara Family and Children’s Services

(905) 937-7731

Phil Howe, Branch Director,

The Children’s Aid Society of Toronto

(416) 924-4646

Bea Kemp, Executive Director,

The Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Hamilton

(905) 525-2012

16

Rick Lang, Director of Services,

The Children’s Aid Society of the District of Thunder Bay (807) 343-6100

Phyllis Lovell, Director of Services,

The Children’s Aid Society of Owen Sound and the

County of Grey

(519) 376-7893

Nancy Macdonald, Quality Assurance Manager,

Algoma Children’s Aid Society

(705) 949-0162

Nancy MacGillivray, Director of Services,

Halton Children’s Aid Society

(905) 333-4441

Kim Martin, Supervisor, Ongoing Protection Service,

The Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Hamilton

(905) 525-2012

Greg Moon, Director of Service,

The City of Kingston and the County of Frontenac

Children’s Aid Society

(613) 542-7351

Michael Mulroney, Senior Social Worker,

The Children’s Aid Society of Ottawa

(613) 747-7800

Darlene Niemi, Supervisor,

The Children’s Aid Society of the District of Thunder Bay (807) 343-6100

Michael O’Brien, Supervisor,

Renfrew Family and Children’s Services

(613) 736-6866

Rocci Pagnello, Director of Services,

Leeds-Grenville Family and Children’s Services

(613)498-2100

Juanita Parent, Family Services Worker,

Native Services Branch, Brant Children’s Aid Society

(519)-445-2247

Jolan Rimnyak, First Response Supervisor,

Niagara Family and Children’s Services

(905) 937-7731

David Rivard, Executive Director,

Sudbury-Manitoulin Children’s Aid Society

(705) 566-3113

Bernard Smith, Executive Director,

Bruce Children’s Aid Society

(519) 881-1822

17

Marilyn Sinclair, Intake Supervisor,

The Children’s Aid Society of the District of Thunder Bay (807) 343-6100

Susan Verrill, Intake and Family Services Director,

Dilico Ojibway Child and Family Services

(807) 622-9060

Lori Watts, Director of Services,

Dilico Ojibway Child and Family Services

(807) 622-9060

Champion

David Rivard, Executive Director,

The Sudbury-Manitoulin Children’s Aid Society

(705) 566-3113

Project Facilitation

Janice Robinson, Director of Services,

Haldimand-Norfolk Children’s Aid Society

(519) 587-5437

Editor

Gary Dumbrill, Assistant Professor & Chair of

Undergraduate Studies, School of

Social Work, McMaster University

(905) 525-9140 ext. 23791

Winnie Lo, Academic Research and Editing Assistant

(905) 525-9140

Project Support and Copy Editor

Paula Loube, Executive Assistant,

The Brant Children’s Aid Society

(519) 753-8681

Project Manager

Andrew Koster, Executive Director,

The Brant Children’s Aid Society

(519) 753-8681

Liaison

Rhonda Hallberg, Director of Intake Services

The London-Middlesex Children’s Aid Society,

Member of the Differential Response Project

(519) 455-9000

Louise Leck, Director of Education,

The Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies

(416) 366-8115

18

Anna Mazurkiewicz, Policy Analyst,

The Secretariat, The Ministry of Children and Youth

(416) 327-2524

Bruce Burbank, Director of Family Services

The Children’s Aid Society of Brant

Family Group Conferencing and Mediation

(519) 753-8681

Raymond Lemay, Executive Director

Prescott-Russell Services to Children and Adults

Looking After Children

(613) 673-5148

Susan Carmichael, Director of Services,

The Children’s Aid Society of Simcoe County

Kinship Care

(705) 726-6587

Contributing Guest Speakers/Authors

David Gill, First Response Supervisor,

Niagara Family and Children's Services

(905) 937-7731

Bruce Leslie, Quality Assurance Manager,

The Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto

(416) 395-1500

Peter Dudding, Executive Director,

Child Welfare League of Canada

(613) 235-4412

George Savoury, Senior Director including

Child Welfare, Government of Nova Scotia

(902) 424-4454

Elizabeth French, Council,

The Children’s Aid Society of Ottawa

(613) 747-7800

Judith Finlay, Chief Child Advocate for Ontario,

The Office of Child and Family Service Advocacy

(Assisted by a Youth Coordinator, and four Youth in Care) (416)-325-5669

Katharine Dill, Doctoral Student in Social Work,

University of Toronto

(416)-978-6314

Gerald de Montigny, Associate Professor,

Faculty of Social Work, Carleton University

(613) 520-2600 ext. 3658

Emmanuelle Antwi, Family Services Supervisor,

Peel Children’s Aid Society

(905)-363-6131

Michael Ansu, Family Services Supervisor,

19

Peel Children’s Aid Society

(905)-363-6131

Judith Wong, Family Services Worker,

Peel Children’s Aid Society

Greta Liupakka, Family Services Worker,

Peel Children’s Aid Society

(905)-363-6131

(905)-363-6131

Sarah Maiter, Associate Professor,

Faculty of Social Work, Wilfrid Laurier University

(519) 884-0710

Bill Lee, Associate Professor,

Faculty of Social Work, McMaster University

(905) 525 9140 ext. 23782

June Ying Yee, Associate Professor,

Faculty of Social Work, Ryerson University

(416)-979-5000 ext. 6224

Non-Project Member Contributors to the Sub-Committee on Assessments

Allison Scott, Director of Services,

Wellington Child and Family Services

(519) 824-2410

Rocco Gizzarelli, Director of Services,

The Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Hamilton

(905) 525-2012

Deborah Goodman, Manager,

The Children’s Aid Society of Toronto

(416) 395-1500

Sandy Moshenko, Director of Services,

Waterloo Family and Children’s Services

(519) 576-0540

Phases of the Project

The OACAS Zone Chairs and its Executive Director Section approved the project and a

committee was formed. Once work was underway it quickly became evident that

identifying and achieving best casework practice with child protection clients not only

required an examination of micro casework processes, but an examination of the agency,

policy and societal contexts in which casework is undertaken. Indeed, workers do not

interact with clients in a vacuum; a broad range of variables governs their work. The

committee, therefore, expanded its focus to examine the broader agency and policy

contexts that shape practice. In producing this Position Paper the committee:

o Conducted an extensive review of research and literature on the most effective

ways to deliver child welfare intervention. This review included an examination

of policy and practice in child welfare jurisdictions around the world including the

USA (particularly Minnesota, and North Carolina) Australian and Britain

20

o Examined Ontario research on child welfare staff retention

o Initiated and completed research on best child welfare practice: Focus groups

were conducted with hundreds of front-line and management staff in numerous

Children’s Aid Societies across Ontario. Separate Aboriginal focus groups

elicited responses from Aboriginal child welfare staff. The results of this research

have been incorporated into project recommendations and are also compiled and

attached separately in an auxiliary document entitled, “Survey of worker

responses to the issues raised by the Position Paper on enhancing client-worker

relationships and collaboration.” This research initiative was taken by the

committee to tap practice wisdom regarding the most effective forms of

intervention and to also ensure that the project recommendations were viable from

a worker and agency perspective

o Examined the practice impact of Child Welfare Reform and in particular the ways

assessment and treatment plans are used. This examination became more

important when two OACAS Projects, Differential Response and the Kinship

Care, both endorsed the place of comprehensive assessments and treatment plans

in providing adequate case planning and protection for children. To assist the

committee in this area, representatives from the Secretariat joined this project,

first a liaison representatives and later as full committee members These members

helped ensure that the project recommendations complemented the other child

welfare initiatives that are due to be implemented in 2005

o Invited child welfare experts ranging from academics to child protection

managers and to present research and other data that identifies the most effective

forms of intervention

Overview of Collaborative Child Welfare: A Model for Ontario

The Ontario child welfare reforms of the late 1990s and early 2000s brought:

o A reminder that child safety must always be paramount

o System enhancement that ensure workers pay attention to safety issues and are

accountable for doing so

o Increased supervisory involvement in case decisions

o Training that ensures staff have knowledge about pathology and indicators related

to the abuse and/or neglect of children

o Higher forensic investigation standards

o Staff who scrutinize the effectiveness of their interventions and do not personalize

the need for their clients to be successful

o An awareness that in some defined instances some forms of relationship can be

ineffectual and in fact increase the possibility of abuse

o Better documentation and record keeping systems

These reforms increased the capacity of the Ontario child welfare system to investigate

and intervene in families where child abuse and neglect was occurring, or was suspected

21

to be occurring, or where it was thought likely to occur in the future. However, the

reforms also inadvertently compromised the ability of agencies to deliver social work

services that protect children in their own communities and homes. A focus on forensic

investigation and regulating parents2 reduced the system’s capacity to use social work

methods that bring child protection changes in families and communities. Indeed, this

shift has been so substantial that some now see social work intervention and the

development of a Casework relationship with parents as an inessential part of child

protection practice. The shift toward investigating and regulating families and an

increased emphasis on liability and a fear of error resulted in an increase of children

being removed from their homes as a protection strategy. This resulted in a 63% increase

of children in care from 1998 to 2004. As budgets are affected by expenditures for

children in care, as well as associated legal costs and additional staff, the annual cost of

delivering child protection services in Ontario increased by 115% from $542 million in

1998 to $1.16 billion in 2004.

Concerned about these trends, in 2001 the Directors of Services of Ontario Children’s

Aid Societies, prepared a discussion paper entitled, “A Critical Analysis of the Evolution

of Reform.” Their paper called for a “rebalancing of priorities to enable a viable, clientcentered protection service.” This Position Paper builds on that work by solidifying the

increased awareness of child safety brought by reform while also identifying and

outlining ways that social work intervention can be utilized to better protect children in

their own homes and communities. As stated in our terms of reference, the committee

was to:

Explore the current clinical “well being” of the practice of social work in the field

of child welfare and to make recommendations for enhancing its clinical

application in Ontario. The project will explore individual worker interaction with

clients who are either being investigated or with whom there is a need to develop

a service plan and an ongoing working relationship. The project will always hold

a child’s safety and well being as the paramount goals of intervention.

(Referenced from Appendix 1, The Project’s Terms of Reference,).

Based on this exploration, the committee was to identify child protection practice

approaches that engage parents and communities in intervention that is directly linked to

improved safety and well being outcomes for children. This committee was to outline

ways that the identified practice approaches could by adopted by the Ontario child

welfare system.

The committee’s work is now complete and we recommend a child welfare policy and

practice shift in Ontario toward what we have called a “collaborative intervention model”

for Ontario. Within this approach, when delivering intervention they will utilize the a

casework approach or approaches best suited to each Children’s Aid Society based on the

following principles:

We use the term “parent” through this Position Paper to refer to a child’s primary caregivers and we

recognize that such “parents” may be a step-parent, grandparent, older sibling or any other adult who is a

primary caregiver for a child.

2

22

o Child safety and well being is the paramount intervention objective

o Children are best protected when parents and workers work together toward these

ends

o To facilitate collaboration workers must draw on casework principles that have

been proven to be effective in child protection work

o Where children are at risk of harm (as defined by child welfare legislation) and

parents are unwilling or unable to collaborate with workers to reduce this risk,

workers must implement a protection plan that does not rely on parental

collaboration or participation

Collaboration in our model operates at intersecting levels. Of course, in child welfare,

collaboration with parents is not always possible, yet the committee found extensive

evidence that where collaboration is possible, this is the most effective means of ensuring

child safety. The collaboration we suggest, however, is not simply at the worker-parent

level. We suggest a shift in the way that protecting children is conceptualized and

delivered; a shift away from seeing “child protection” as intervention as a micro service

delivered by a Children’s Aid Society and a shift toward seeing it as a community

response coordinated by a Children’s Aid Society.

The committee suggests, therefore, that we must go beyond these principles. To consider

an individual worker and parent collaborating together as an adequate provision for

children who are in need of protection oversimplifies the issues involved in such work.

The child protection worker operates in a legal and institutional context that shapes their

work. The child protection worker’s agency operates within context of other institutions

and social service agencies all of which contribute to the well being of families and

children. As well, parents operate within a societal context that provides both

opportunities and constraints on their ability to parent. Consequently an Ontario model of

collaborative child welfare needs to have those operating in all collaborating together in

the interests of children. It is not sufficient to see intervention and collaboration as a

micro endeavor that occurs between a worker and parent—it must be seen as a process in

which society as a whole can participate.

The “collaborative child welfare model” developed by the committee will benefit and

improve child protection services to children and their families in Ontario. Developing a

model is not an uncommon exercise for jurisdictions that are re-evaluating their child

welfare services - jurisdictions in Australia and the United States have developed local

models. The committee looked at several of these models, particularly those in

Minnesota and North Carolina and also a model developed in Australia by Andrew

Turnell based on his book ‘Signs of Safety’ (Turnell & Edwards, 1999). We have

included concepts from these models in this Position Paper but ultimately we recognized

that Ontario required its own model. The province is unique in geography and in the

societal, cultural and economic diversity existing within the region. Also, the province’s

child welfare system is operated at local levels through Children’s Aid Societies managed

by their own independent Boards and management teams who are aware of the child

welfare needs and challenges in their own communities. The model was developed, as an

23

overarching province-wide approach to “collaborative service” delivery that is refined

and tailored to meet local community needs by each agency.

Ideally, at the heart of intervention, a parent will collaborate with a Children’s Aid

worker to address child protection concerns. Supporting this worker-parent relationship

will be collaboration at broader levels between the worker and community

agencies/resources that ensure a parent can access help to appropriately care for their

children. In instances where worker-parent collaboration is not possible, the worker will

implement a protection plan independent of the parent but this will not be independent

from the collaboration and support of the broader community. Under this model a

Children’s Aid Society coordinates child protection but it is also the concern and

responsibility of the entire community. This model not only calls for workers to develop

collaborative relationships with parents to help enhance their capacity to protect and care

for their children, but also calls for workers to develop collaborative relationships with

communities to help enhance its capacity to protect and care for children. As such the

model conceptualizes child protection as everybody’s responsibility in a similar way to

the vision captured in the proverb, “it takes a village to raise a child.” In Africa where

this proverb originates, a “high context” (Hall, 1976) culture and community collectively

(Battle, 1997) ensures that people understand that the dynamic behind a village raising

children is the collaboration inherent in a village community. This meaning can be lost in

individualistic western societies - consequently to understand the proverb we emphasize

that, “it takes a village ‘that collaborates’ to raise a child.”

The efficacy and need for a collaborative model is supported by the literature and

research examined in this paper and is consequently based on:

o Evidence that children are best protected when workers and parents collaborate

toward promoting child welfare (Farmer & Owen, 1995; J Thoburn, 1992; Trotter,

2002, 2004)

o Evidence that workers must collaborate with children and youth when delivering

child protection intervention (Finlay & Snow, 1998)

o Evidence that supervisors and managers must be a part of the collaborative

process (Bloom-Cooper, 1985; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988b,

1991; Home Office et al., 1991)

o Evidence that inter-agency collaboration is crucial to protecting children (BloomCooper, 1985; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988b, 1991)

o Evidence that whole communities need to work together in protecting children

(Bloom-Cooper, 1985; Department of Health and Social Security, 1988, 1991)

o Evidence that government and policy makers must move beyond making

reactionary pendulum swings in child welfare policy and practice (Reder et al.,

1993)

o Evidence that academic researchers and practitioners need to collaborate to

measure intervention outcomes and identify best practice (Leslie, 2005; Trocmé,

2005; Vandermeulen et al., 2005; VanWilgenburg, 2005)

Because collaboration is involved in all the above, the elements of our model are not

new, but combining of them into a “collaborative child welfare model” is new. We

24

suggest that this model become the foundation on which the transformation of the

Ontario child welfare be based.

We envision our model will be implemented in different ways across the province.

Tailoring this model for each community is crucial because communities such as

Attawapaskat, Toronto, and Timmins are distinct; the 143 different First Nations within

the province each differ, and the various immigrant and ethno-racial communities have

diverse needs. To be viable a model has to meet the unique strengths, needs and

resources within these diverse communities. The Ontario system can respond to these

differing needs because the child protection system is governed by 53 child welfare

agencies comprised of local community members who can ensure that each agency

responds and collaborates with its constituents in the most appropriate manner. Our

collaborative model is designed, therefore, to be implemented by child welfare agencies

that are a part of these local communities and are aware of their local needs.

25

SECTION 2: A COLLABORATIVE INTERVENTION MODEL

Introduction

Protecting children is the primary objective of child welfare intervention. The Ontario

reforms were a needed reminder of this imperative and they enhanced the ability of the

child welfare system to focus on child safety and to remove children when their safety at

home could not be assured. The reforms brought many benefits including:

o A reminder that child safety must always be paramount

o A system that ensures workers pay attention to safety issues and are accountable

for doing so

o Increased supervisory involvement in case decisions

o Training that ensures staff have knowledge about pathology and indicators related

to the abuse and/or neglect of children

o Higher forensic investigation standards

o Staff who scrutinize the effectiveness of their interventions and do not personalize

the need for their clients to be successful

o An awareness that in some forms of worker-parent relationship can be ineffectual

and in fact increase the possibility of abuse

o Better documentation and record keeping systems

There is, however, a need to build on the reform initiatives by enhancing the ability of the

of the child welfare system to protect children in their own homes and communities. The

model we propose for building on reform is one of “collaboration.”

A move toward collaboration is not a move away from a focus on child safety nor is it a

move toward formulating unviable safety plans with reluctant families. Rather, a

collaborative model retains child safety as the prime directive of intervention but it

expects child protection workers to utilize social work skills in assessing a family’s

openness to protect their children and to then employ intervention skills and strategies to

help the family bring about the required protective change.

A shift toward collaboration, therefore, does not send child welfare practice in a

completely different direction but it does adjust the field. The need for adjustment has

been seen for some time. A paper put forward by the provincial Directors of Service in

2001 called for the rebalancing of child welfare priorities “to enable a viable client

centered protection service” (Provincial Directors of Service, 2001). This statement

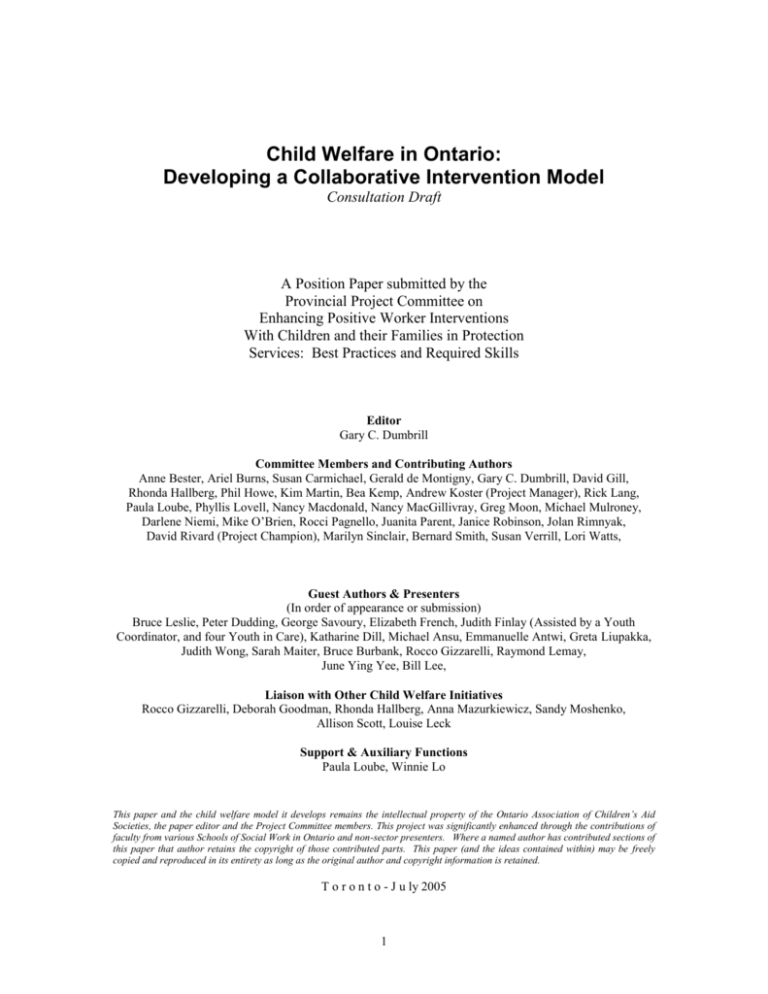

embodies the focus of our project and is also portrayed in figure 1.

26

Figure 1: An Opportunity for a Pendulum Swing Towards the Middle While Still

Ensuring Child Safety

Transformation

An Opportunity for a Swing towards the Middle?

Child in Need of

Protective Services

The Grab

1960’s to

Mid 70’s

Family Preservation

1980’s to 2000

ORAM

2000 to 2005

Risk Reduction,

Inspectoral Approach

Transformation

Think Dirty, Deficit-based,

Liability focused, Adversarial &

Formulaic

2005 +…?

Blind Faith or Optimistically

Naïve Approach

Either “Trust us we are the experts” or

“They are oppressed by Society, it is

not their fault” & we then ignore signs

of safety & enable further harm

Research-Based, Collaborative Best Practice

Approach

Outcome focused, Evidenced based, Collaborative

Relationships with Clients

Figure by Rocci Pagnello, 2005

Figure 1 shows the ways child protection policy and practice swings back and forth

between family preservation and child safety. This oscillation between family

preservation and child safety is an internationally recognised phenomenon in child