Cable in the Classroom: Shakespeare adaptation

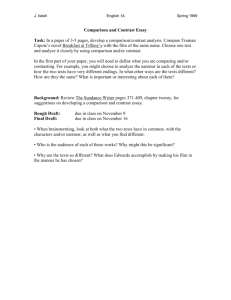

advertisement