Reading 3

advertisement

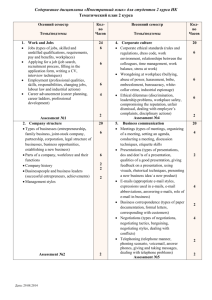

“DEMOGRAPHY” STUDENT’S FILE (4.5 weeks: 10 April – 15 May) PLAN I. Lead-in Reading 1: POPULATION PESSIMISM REDUX II. Obligatory material Reading 2: THE DEMOGRAPHIC TIME BOMB TRANSFORMING OUR CONTINENT Reading 3: GENDERCIDE: THE WORLDWIDE WAR ON BABY-GIRLS III. Additional texts Reading 4: WHY BRITAIN NEEDS POLISH MIGRANTS Reading 5: THE OTHERS Reading 6: ECONOMIC CRISIS SABOTAGES RUSSIA’S EFFORTS TO HALT FALLING POPULATION К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 1 I. Lead-in Reading 1: Population Pessimism Redux Population Aging and Economic Growth David E. Bloom, David Canning, 2008 For most of the twentieth century the dominant issue in the field of demography was the explosion in population numbers caused by the lowering of mortality rates coupled with continuing high fertility rates. The predicted negative consequences of high population densities, and a high population growth rate, seem not to have been borne out. Many of the predictions made about the effects of population growth seem in retrospect to have been unduly alarmist. For example, between 1960 and 1999, global population doubled, rising from 3 to 6 billion, but income per capita tripled, decisively refuting the predictions of population pessimists from Malthus to Ehrlich.* Following the 1986 National Academy of Sciences’ report on population growth, the nonalarmist position came to dominate economists’ thinking on population. While rapid population growth posed problems, the report argued that market mechanisms and non-market institutions were usually sufficiently flexible to ameliorate those problems. Changing incentives through price changes, and changing non-market institutional arrangements to promote new behaviors, could have large effects and produce responses that would alleviate the problems associated with population growth. The population debate focused on population numbers and missed to a large extent the issue of age structure changes. Population growth caused by rising fertility and population growth caused by falling mortality are likely to have quite different economic consequences because they have different age structure effects. However, it is important to remember the lessons of the earlier debate. Analysis based on “accounting effects,” in particular on the assumption that age-specific behavior remains unchanged, may be misleading. When this type of analysis predicts large reductions in welfare we should be particularly suspicious since these are exactly the conditions that will produce incentives for behavioral change. This reasoning also applies to an assessment of the economic growth implications of continued improvements in health and reductions in mortality into old age, coupled with the aging of the baby boom generation. How well countries cope with the challenge of population aging will likely depend to a large extent on the flexibility of their markets and the appropriateness of their institutions and policies. An Uncertain Future Of course, humility is required when making decisions based on future demographic projections. The sources of uncertainty remain considerable. Population projections, for example, are not cast in stone. The possibility of changes in fertility behavior or health shocks could tilt the balance between young and old in unforeseen ways. Projections of population size and structure can change quite significantly even over short periods. Longevity projections are also precarious and hotly debated. Trends in diet and lifestyle as well as medical and public health advances could combine to raise or lower life expectancy in future. Technology has a crucial role to play. The compression of morbidity** occurring today is partly driven by new health technology, but it is uncertain whether technological advance will continue, diminish, or accelerate in future, and what cost implications it will have. Trends such as the obesity “epidemic” could dampen the positive effects of technology. The WHO projects that by 2025 300 million people will be obese; the WHO also notes that the health impacts of rising obesity prevalence could reverse life К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 2 expectancy gains in some countries. Non-health related events such as climate change or war could also have an unpredictable effect on longevity. Nor is it clear whether the economic impacts of aging will be uniform across societies. In the developed world, longer lifespan has been accompanied by a shift in support for older generations from families to the state. In many developing countries, families remain pivotal to elder care and as lifespan becomes longer there may be disruption to family structures, leading to a similar move towards public transfer systems and savings as that experienced in wealthier parts of the world. Although drawing lessons from the past may not be possible for an aging future, we do know that some societies in the past century have coped well with the major demographic shift represented by population growth. The world economy has had the flexibility to absorb and in general benefit from dramatic increases in population numbers. If today’s policy makers take prompt action to prepare for the effects of aging, the next major shift is likely to cause much less hardship than many fear. One view is that population aging in the developed countries is likely to have a large effect, reducing income per capita, mainly through the fall in labor supply per capita that will accompany the reduction in the share of working-age population. However, even if this occurs, it may not be as harmful as it at first appears. Notes: *According to Malthus, who wrote around 1800, when world population first crossed the 1 billion mark, “…[population growth] appears … to be decisive against the possible existence of a society, all the members of which should live in ease, happiness, and comparative leisure; and feel no anxiety about providing the means of subsistence for themselves and families” (Malthus 1798). In a similar vein, Paul Ehrlich asserted in the late 1960s, that “The battle is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death” (Ehrlich 1968). ** the compression of morbidity - is a term used to describe one of the goals of healthy aging and longevity – the goal of minimizing the number of years that a person spends suffering from age-related disease while maximizing the total number of years. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 3 II. Obligatory material Reading 2: The demographic time bomb transforming our continent The EU is facing an era of vast social change and few politicians are taking notice By Adrian Michaels Aug 2009 Britain and the rest of the European Union are ignoring a demographic time bomb: a recent rush into the EU by migrants, including millions of Muslims, will change the continent beyond recognition over the next two decades, and almost no policy-makers are talking about a looming crisis. The numbers are startling. Only 3.2 per cent of Spain's population was foreign-born in 1998. In 2007 it was 13.4 per cent. Europe's Muslim population has more than doubled in the past 30 years and will have doubled again by 2015. In Brussels, the top seven baby boys' names recently were Mohamed, Adam, Rayan, Ayoub, Mehdi, Amine and Hamza. Europe's low white birth rate, coupled with faster multiplying migrants, will change fundamentally what we take to mean by European culture and society. The altered population mix has far-reaching implications for education, housing, welfare, labour, the arts and everything in between. It can have a critical impact on foreign policy. Yet EU officials admit that these issues are not receiving the attention they deserve. Jerome Vignon, the director for employment and social affairs at the European Commission, said that the focus of those running the EU had been on asylum seekers and the control of migration rather than the integration of those already in the bloc. "It has certainly been underestimated - there is a general rhetoric that social integration of migrants should be given as much importance as monitoring the inflow of migrants." But, he said, the rhetoric had rarely led to policy. The countries of the EU have long histories of welcoming migrants, but in recent years two significant trends have emerged. Migrants have come increasingly from outside developed economies, and they have come in accelerating numbers. The growing Muslim population is of particular interest. This is not because Muslims are the only immigrants coming into the EU in large numbers; there are plenty of entrants from all points of the compass. But Muslims represent a particular set of issues beyond the fact that atrocities have been committed in the West in the name of Islam. America's Pew Research Center said in a report: "These [EU] countries possess deep historical, cultural, religious and linguistic traditions. Injecting hundreds of thousands, and in some cases millions, of people who look, speak and act differently into these settings often makes for a difficult social fit." How dramatic are the population changes? Everyone is aware that certain neighbourhoods of certain cities in Europe are becoming more Muslim, and that the change is gathering pace. But raw details are hard to come by as the data is sensitive: many countries in the EU do not collect population statistics by religion. EU numbers on general immigration tell a story on their own. In the latter years of the 20th century, the 27 countries of the EU attracted half a million more people a year than left. "Since 2002, however," the latest EU report says, "net migration into the EU has roughly tripled to between 1.6 million and two million people per year." The increased pace has made a nonsense of previous forecasts. In 2004 the EU thought its population would decline by 16 million by К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 4 2050. Now it thinks it will increase by 10 million by 2060. Britain is expected to become the most populous EU country by 2060, with 77 million inhabitants. Italy's population was expected to fall precipitously; now it is predicted to stay flat. According to the US's Migration Policy Institute, residents of Muslim faith will account for more than 20 per cent of the EU population by 2050 but already do so in a number of cities. Whites will be in a minority in Birmingham by 2026 and even sooner in Leicester. Another forecast holds that Muslims could outnumber nonMuslims in France and perhaps in all of Western Europe by mid-century. Projected growth rates are a disputed area. Birth rates can be difficult to predict and migrant numbers can ebb and flow, of course. Recent polls have tended to show that the feared radicalisation of Europe's Muslims has not occurred. That gives hope that the newcomers will integrate successfully. Nonetheless, second and third generations of Muslims show signs of being harder to integrate than their parents. Policy Exchange, a British study group, found that more than 70 per cent of Muslims over 55 felt that they had as much in common with non-Muslims as Muslims. But this fell to 62 per cent of 16-24 year-olds. The EU says employment rates for non-EU nationals are lower than for nationals, which holds back economic advancement and integration. One important reason for this is a lack of language skills. Overall in 2008, 14.4 per cent of children in primary schools had a language other than English as their first language. The population changes are stirring unease on the ground. Europeans often tell pollsters that they have had enough immigration, but politicians largely avoid debate. France banned the wearing of the hijab veil in schools and stopped the wearing of large crosses and the yarmulke too, so making it harder to argue that the law was aimed solely at Muslims. Muslims, who are a hugely diverse group, have so far shown little inclination to organise politically on lines of race or religion. But that does not mean their voices are being ignored. Germany started to reform its voting laws 10 years ago, granting certain franchise rights to the large Turkish population. Britain has strengthened its laws on religious hatred. But these are generally isolated pieces of legislation. Into the void has stepped a resurgent group of extreme-Right political parties, among them the British National Party, which gained two seats at recent elections to the European Parliament. Geert Wilders, the Dutch politician who speaks against Islam and was banned this year from entering Britain, has led opinion polls in Holland. The fact that extreme parties have risen to prominence at all speaks poorly about the state and quality of the immigration debate. European elites have yet to fully grapple with the broader issues of race and identity surrounding Muslims and other groups. The starting point should be greater discussion of integration. Does it matter at all? Yes! Without it, polarisation and ghettoes can result. Without it, every new influx of immigrants will exacerbate tensions and hinder assimilation. Demography will force politicians to confront these issues sooner rather than later. Recently, some have started to spark off the debate. Angel Gurría, the OECD secretary-general, said in June: "Migration is not a tap that can be turned on and off at will. We need fair and effective migration and integration policies; policies that work and adjust to both good economic times and bad ones." Ex.1 Suggest Russian equivalents for these word combinations from the text, reproduce the context in which they are used in the text. 1. a demographic time bomb 2. to change beyond recognition 3. a looming crisis К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 5 4. a general rhetoric 5. inflow of migrants // influx of immigrants 6. plenty of entrants from all points of the compass 7. the most populous EU country 8. outnumber non-Muslims 9. projected growth rates 10. to stir unease 11. exacerbate tensions 12. hinder assimilation 13. spark off the debate Ex.2 Continue the following strings of collocations with the words in bold. Use some of the word combinations in sentences of your own. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. a looming crisis, __________, __________, _________ projected growth rates, ___________, ___________, __________ to exacerbate tensions, ____________, ___________, ___________ hinder assimilation, ____________, ___________, ___________, ___________ to spark off a debate, ___________, ___________, ___________, ___________ Ex.3 Fill in the gaps using the words and expressions from Ex.1 and Ex.2. 1. The _________ of immigrants appears likely to _________ _________ between some minority groups, particularly blacks, and immigrants. 2. Over the last 50 years the population has _________ _________ ________ so that these days the tag "Leicester born and bred" applies to people whose parents have settled here from all corners of the world. 3. A _______ _________ _________ is a potential crisis situation in most countries characterized by an increasing number of older people dependent on pension schemes. 4. If Afghanistan's growth rate remained the same (the country's ________ growth rate for 2025 is a mere 2.3%), then the population of 30 million would become 60 million in 2020. 5. Bishop Dr. Zac Niringiye has warned of a _______ _________ in Uganda if the population growth rate is not drastically reduced. 6. David Cameron has announced that he would abolish the climate change tax, but he has still not put forward a concrete alternative. This is yet another example of more empty ________ from the Tories. 7. The bill is starting to _______ _________, because it requires private organizations to make decisions that conflict with their deeply held beliefs. 8. In fact, demographers say this year could be the "tipping point" when the number of babies born to minorities ________ that of babies born to whites. 9. As Spain plunged into recession in 2009 the _________ of immigrants has slowed drastically and many foreign nationals have returned to their home countries after losing their jobs. 10. The United States began negotiations with Poland and the Czech Republic to install a radar and missile interceptors, angering Russia and _______ _______ in some European countries. 11. While the prolonged recession has led to a certain slowing of the influx of foreign _________ in Japan, the number of foreign residents in Japan has continued to increase. 12. India will become the most _________ country overtaking China by 2050, the United Nation Population Fund (UNFPA) has projected. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 6 13. A landmark speech by Javier Solana was set to _________ the debate on future relations between the US and the EU after the huge damage created by the American-led preventative war against Iraq. 14. We are fighting against discriminations such as school segregation and covert racism in jobs that _________ ___________ of our group into the society. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 7 Reading 3: Gendercide: the worldwide war on baby girls Technology, declining fertility and ancient prejudice are combining to unbalance societies The Economist print edition, March 2010 In January 2010 the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) showed what can happen to a country when girl babies don’t count. Within ten years, the academy said, one in five young men would be unable to find a bride because of the dearth of young women—a figure unprecedented in a country at peace. The number is based on the sexual discrepancy among people aged 19 and below. According to CASS, China in 2020 will have 30m-40m more men of this age than young women. So within ten years, China faces the prospect of having the equivalent of the whole young male population of America with little prospect of marriage, not attached to a home of their own and without the stake in society that marriage and children provide. Gendercide—to borrow the title of a 1985 book by Mary Anne Warren—is often seen as an unintended consequence of China’s one-child policy, or as a product of poverty or ignorance. But that cannot be the whole story. The surplus of bachelors—called in China guanggun, or “bare branches”— seems to have accelerated between 1990 and 2005, in ways not obviously linked to the one-child policy, which was introduced in 1979. And, as is becoming clear, the war against baby girls is not confined to China. Parts of India have male/female ratios as distorted as anything in its northern neighbour. Other East Asian countries—South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan—have peculiarly high numbers of male births. Former communist countries in the Caucasus and the western Balkans have been following suit since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The real cause, argues Nick Eberstadt, a demographer and a think-tank in Washington, DC, is not any country’s particular policy but “the fateful collision between a discernible son preference, the use of rapidly spreading prenatal sex-determination technology and declining fertility.” These are global trends. And the selective destruction of baby girls is global, too. Boys are slightly more likely to die in infancy than girls. To compensate, more boys are born than girls so there will be equal numbers of young men and women at puberty. In all societies between 103 and 106 boys are normally born for every 100 girls. The ratio has been so stable over time that it appears to be the natural order of things. That order has changed fundamentally in the past 25 years. According to CASS the sex ratio in China today is 123 boys per 100 girls. As CASS says, “the gender imbalance has been growing wider year after year.” These rates are biologically impossible without human intervention. South Korea is experiencing some surprising consequences of similar gender imbalance. The surplus of bachelors in a rich country has sucked in brides from abroad. In 2008, 11% of marriages were “mixed”, mostly between a Korean man and a foreign woman. This is causing tensions in a hitherto homogeneous society, which is often hostile to the children of mixed marriages. The trend is especially marked in rural areas, where the government thinks half the children of farm households will be mixed by 2020. The children have produced a new word: “Kosians”, or Korean-Asians. Conventional wisdom about such sexual disparities is that they are the result of “backward thinking” in old-fashioned societies or—in China—of the one-child policy. By implication, reforming the policy or modernising the society (by, for example, enhancing the status of К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 8 women) should bring the sex ratio back to normal. But this is not always true and, where it is, the road to normal sex ratios is winding and bumpy. Not all traditional societies show a discernible preference for sons over daughters. But in those that do—especially those in which the family line passes through the son and in which he is supposed to look after his parents in old age—a son is worth more than a daughter. A girl is deemed to have joined her husband’s family on marriage, and is lost to her parents. As a Hindu saying puts it, “Raising a daughter is like watering your neighbours’ garden.” Until the 1980s people in poor countries could do little about their son preference: before birth, nature took its course. But in that decade, ultrasound scanning and other methods of detecting the sex of a child before birth began to make their appearance. These technologies changed everything. Doctors in India started advertising ultrasound scans with the slogan “Pay 5,000 rupees ($110) today and save 50,000 rupees tomorrow” (the saving was on the cost of a daughter’s dowry). The use of sex-selective abortion was banned in India in 1994 and in China in 1995. It is illegal in most countries (though Sweden legalised the practice in 2009). But since it is almost impossible to prove that an abortion has been carried out for reasons of sex selection, the practice remains widespread. Sexual disparities tend to rise with income and education, which you would not expect if “backward thinking” was all that mattered. In India, some of the most prosperous states— Maharashtra, Punjab, Gujarat—have the worst sex ratios. In China, the higher a province’s literacy rate, the more skewed its sex ratio. The ratio also rises with income per head. Modernisation and rising incomes make it easier and more desirable to select the sex of your children. And on top of that smaller families combine with greater wealth to reinforce the imperative to produce a son. If you have only one or two children, the birth of a daughter may be at a son’s expense. So, with rising incomes and falling fertility, more and more people live in the smaller, richer families that are under the most pressure to produce a son. The hazards of bare branches Throughout human history, young men have been responsible for the vast preponderance of crime and violence—especially single men in countries where status and social acceptance depend on being married and having children, as it does in China and India. A rising population of frustrated single men spells trouble. The crime rate has almost doubled in China during the past 20 years of rising sex ratios, with stories abounding of bride abduction, the trafficking of women, rape and prostitution. A study into whether these things were connected concluded that they were, and that higher sex ratios accounted for about one-seventh of the rise in crime. In India, too, there is a correlation between provincial crime rates and sex ratios. The social problems of biased sex ratios could even lead to more authoritarian policing. Governments must decrease the threat to society posed by these young men. Increased authoritarianism in an effort to crack down on crime, gangs, smuggling and so forth can be one of the results. Violence is not the only consequence. In parts of India, the cost of dowries is said to have fallen. Where people pay a bride price that price has risen. During the 1990s, China saw the appearance of tens of thousands of “extra-birth guerrilla troops”—couples from one-child areas who live in a legal limbo, shifting restlessly from city to city in order to shield their two or three children from the authorities’ baleful eye. And, according to the World Health Organisation, female suicide rates in China are among the highest in the world (as are South Korea’s). Suicide is the К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 9 commonest form of death among Chinese rural women aged 15-34 who cannot live with the knowledge that they have killed their baby daughters. Some of the consequences of the skewed sex ratio have been unexpected. It has probably increased China’s savings rate. This is because parents with a single son save to increase his chances of attracting a wife in China’s ultra-competitive marriage market. About half the increase in China’s savings in the past 25 years can be attributed to the rise in the sex ratio. Over the next generation, many of the problems associated with sex selection will get worse. The social consequences will become more evident because the boys born in large numbers over the past decade will reach maturity then. Meanwhile, the practice of sex selection itself may spread because fertility rates are continuing to fall and ultrasound scanners reach throughout the developing world. Yet the story of the destruction of baby girls does not end in deepest gloom. At least one country—South Korea—has reversed its cultural preference for sons and cut the distorted sex ratio. There are reasons for thinking China and India might follow suit. Though it takes a long time for social norms favouring sons to alter, and though the transition can be delayed by the introduction of ultrasound scans, eventually change will come. Modernisation not only makes it easier for parents to control the sex of their children, it also changes people’s values and undermines those norms which set a higher store on sons. At some point, one trend becomes more important than the other. Though the two giants are much poorer than South Korea, their governments are doing more than it ever did to persuade people to treat girls equally (through anti-discrimination laws and media campaigns). The unintended consequences of sex selection have been vast. They may get worse. But, at long last there seems to be an incipient turnaround in the phenomenon of “missing girls” in Asia. Ex.4 Suggest Russian equivalents for these word combinations from the text, reproduce the context in which they are used in the text. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. the dearth of young women sexual discrepancy // disparities unintended consequence the surplus of bachelors male/female ratio // sex ratio a distorted ratio to follow suit a discernible son preference // to show a discernible preference for sons over daughters 9. prenatal sex-determination technology 10. declining // falling fertility 11. gender imbalance 12. a hitherto homogeneous society 13. backward thinking 14. spell trouble 15. the authorities’ baleful eye Ex.5 Continue the following strings of collocations with the words in bold. Use some of the word combinations in sentences of your own. 1. sexual, ___________, ___________, ___________ discrepancy К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 10 2. 3. 4. 5. distorted ratio, __________, __________, ___________ a discernible preference, __________, __________, __________ homogeneous society, ___________, ___________, ___________ spell trouble, __________, __________, __________ Ex.6 Fill in the gaps using the words and expressions from Ex.4 and Ex.5. 1. The new recruitment policies _________ _________ as men lacking even an elementary education were entering an organization whose greatest demand was for personnel with high technical qualifications. 2. In less developed nations the gender _________ in life expectancy is smaller than in the developed nations, and it has increased in favor of women in the last 35. 3. Whether a country of integration or of a melting pot, America thrives and has always thrived due to the __________ of immigrants finding refuge in America. 4. An __________ __________ comes about when a mechanism that has been installed in the world with the intention of producing one result is used to produce a different (and often conflicting) result. 5. The human _________ __________ is the number of males for each female in a population. 6. Ukraine's accession to the World Trade Organization will encourage Belarus to _________ __________. 7. Simplest conclusion is that the __________ of women scientists is caused largely by bias and social factors. 8. Make sure that you are actually comfortable with the instructor as there is nothing worse than operating under the __________ __________ of a teacher you simply detest. 9. Mr. Camby has no ___________ ___________ between alligator and crocodile but says his favorite reptile ''is a dead one.'' 10. _________ __________ leads to backward behaviour, backward behaviour leads to backward society, backward society leads to exploitation and corruption. 11. If parents are given the opportunity to choose the sex of their child and if children of one sex are preferred this will result in a __________ sex ratio among children and adults. 12. The Indian Parliament had to pass a law regulating medical use of __________ technology and made it illegal to advertise such services. 13. The grave consequences of _________ have escaped public attention because of the great concern during the past decades about overpopulation. 14. Seriously though, there is a _________ __________ in Russia, due to the shortage of Russian men Russian women have no option but to marry foreigners. 15. A ___________ society is such a society where most of the people share the same type of cultural values, language, ethnicity and religious system. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 11 III. Additional texts Reading 4: Why Britain needs Polish migrants By Wiktor Moszczynski Telegraph.co.uk, 2008 Their lordships have spoken. Their 82-page report on the economic impact of immigration claims to cover all aspects of the influx into Britain, from the New Commonwealth to the New Europe. But searching through the morass of graphs and witness statements, I failed to find proper recognition of the current status of the ever-visible Polish workers within British society. Perhaps this was because, of those 76 witnesses, not one was a Pole or a Central European. In fact, there was not a single expert witness from any of the new immigrant communities, many of whom have eminent scholars in economics and sociology who could have contributed. Not for the first time, Poles experience a déjà vu of the "Yalta syndrome", so called after the 1945 summit between Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin that carved up eastern Europe. Some of the report's conclusions are predictable. The Federation of Poles in Britain, for which I am spokesman, has long been badgering ministers and MPs about the abysmal lack of reliable statistics for the population here; the resentment felt by those on low incomes or unemployed at the new influx of hard-working Poles; the ruthless exploitation of some of the immigrant workers; the lack of school place provision for the families of new workers locally; and the need to intensify the free English lessons programme. While we supported the Government's controversial decision in 2004 to allow citizens of the new EU states to work in Britain, we were concerned at the lack of foresight regarding the social problems that would accompany such a large influx. Only 13,000 would come every year, said the Government. One of the funniest pages in the report was the appendix that recounted how German social scientists advising the Government got this prediction so terribly wrong. The House of Lords committee report acknowledged that immigrants contributed some £6 billion annually into the economy, but then made the astounding statement that this "was irrelevant". Since when has GDP been irrelevant? It is always an important factor in the measure of any economy. Instead, their lordships stated this increase should be measured on income per head of each indigenous resident, and on that basis they concluded the benefits for these residents "were small". The main beneficiaries, the report claims, are large-scale employers and the immigrants themselves; the losers are those on low incomes, which is then averaged out to mean nearly everybody. The Little Englanders who have consistently opposed immigration took no time to say "I told you so!" and, inevitably, the growing number of "hate crimes" against Poles in rural areas will increase as a result. One could see similar outbursts of rage when earlier immigration of Flemings in the 14th century and Huguenots in the 17th century enriched the English economy, but left a large proportion of the population feeling resentful and destitute. Again, the same happened with the advent of industrialisation, and when the labour market was opened to women. These pockets of resentment occur because the economic gains of society have never been К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 12 evenly distributed among the population and also because the welfare system no longer encourages many indigenous residents to seek work. This is hardly the fault of the immigrant. The million or so Poles who have come here in the past five years definitely came to work. They are three times more likely to be law-abiding than the average British resident, and the 134 Polish Catholic churches are packed. The most dreaded words for a Polish priest are not "mortal sin", but "fire regulations". True, many Poles now go to school here, are treated by the NHS and some receive child benefit, but only three per cent are eligible for other subsidies. There is an extra burden on local health and education authorities and police associations: many of these social costs however are covered by their £1.9 billion a year contribution to the Exchequer in income tax and national insurance, and that figure does not include their contribution to council tax. Their presence has been hugely popular among the middle classes, who needed plumbers and nannies, and welcomed by the catering and construction industries, local public transport and by Scottish agriculture, which they have saved from extinction. Trade unions seek to recruit them. So does the Army. Their work ethic has been praised by employers, customers and fellow workers alike. It is resented, however, by those who feel that the crowded labour market for the unskilled and lowly paid is no longer a level playing field. The report will encourage them to say: "Poles go home". And what if they do leave? Stories that many Poles may be returning to a now more prosperous Poland are a little exaggerated, but have raised panic among employers, particularly in the rural industries. Those who were once belabouring the Poles consistently for their presence will now call them "deserters" for threatening to leave. If only Britain could make up its mind. Reading 5: The others It is becoming both easier and more difficult to experience the thrill of being an outsider The Economist print edition, 2009 FOR the first time in history, across much of the world, to be foreign is a perfectly normal condition. It is no more distinctive than being tall, fat or left-handed. Nobody raises an eyebrow at a Frenchman in Berlin, a Zimbabwean in London, a Russian in Paris, a Chinese in New York. The desire of so many people, given the chance, to live in countries other than their own makes nonsense of a long-established consensus in politics and philosophy that the human animal is best off at home. Philosophers, it is true, have rarely flourished in foreign parts: Kant spent his whole life in the city of Königsberg; Descartes went to Sweden and died of cold. But that is no justification for generalising philosophers’ conservatism to the whole of humanity. The error of philosophy has been to assume that man, because he is a social animal, should belong to some particular society. Herder, an 18th-century Prussian philosopher, launched modern conceptions of nationalism by arguing that a man could flourish only among his own people who shared his language and culture. “Each nationality contains its centre of happiness within itself,” Herder wrote. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 13 Even an exemplary modern liberal philosopher, Isaiah Berlin, found this sort of emotional logic seductive. “Everyone has the right to live in some society in which they needn’t constantly worry about what they look like to others, and so be psychically distorted, conditioned to some degree of mauvaise foi”, Berlin said in 1992, near the end of his life, explaining his support for Zionism. And yes, no doubt many people do feel most at ease with a home and a homeland. But what about the others, who find home oppressive and foreignness liberating? Theirs is a choice that gets both easier and more difficult to exercise with every passing year. Easier, because the globalisation of industry and education tramples national borders. More difficult, because there are ever fewer places left in this globalised world where you can go and feel utterly foreign when you get there. It has long been true in America that nobody can be foreign because everybody is foreign. In the capital cities of Europe that same paradoxical condition has more or less been reached— especially in Brussels, the self-styled capital of Europe, where decades of economic migration have been reinforced by an influx of European Union bureaucrats. There the animosity between Dutch- and French-speaking Belgians makes them foreigners to one another, even in their own country. To get a strong sense of what it means to be foreign, you have to go to Africa, or the Middle East, or parts of Asia. In South Korea last year 42% of the population had never knowingly spoken to a foreigner. Well, they had better get ready. The country’s foreign residents have doubled in the past seven years, to 1.2m, or more than 2% of the population. And that share could rise: the foreign-born average in the rich world is over 8% of a given population. Foreigners par excellence The most generally satisfying experience of foreignness—complete bafflement, but with no sense of rejection—probably comes still from time spent in Japan. To the foreigner Japan appears as a Disneyland-like nation in which everyone has a well-defined role to play, including the foreigner, whose job it is to be foreign. Everything works to facilitate this role-playing, including a towering language barrier. The Japanese believe their language to be so difficult that it counts as something of an impertinence for a foreigner to speak it. Religion and morality appear to be reassuringly far from the Christian, Islamic or Judaic norms. Worries that Japan might Westernise, culturally as well as economically, have been allayed by the growing influence of China. It is going to get more Asian, not less. Even in Japan, however, foreigners have ceased to function as objects of veneration, study and occasionally consumption. Once upon a time, in the ancient and medieval worlds, to count as properly foreign you had to seek out a life among peoples of a different skin colour or religion. They were probably an impossibly long distance away, they might well kill you when you got there, and if you went too far you might fall off the edge of the world. At the dawn of the travelling age, writing an imaginary legal code for a Utopian society that he called Magnesia, Plato divided foreigners into two main categories. “Resident aliens” were allowed to settle for up to 20 years to do jobs unworthy of Magnesians, such as retail trade. “Temporary visitors” consisted of ambassadors, merchants, tourists and philosophers. Broaden that last category to include all scholars, and you have a taxonomy of travellers that held good until the invention of the stag party. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 14 To be foreign got much more straightforward from the 17th century onwards, when Europe adopted a political system based on nation states, each with borders, sovereignty and citizenship. Travel-papers in hand, you could turn yourself into an officially recognised foreigner simply by visiting the country next door—which, with the advance of mechanised transport, became an ever more trivial undertaking. By the early 20th century most of the world was similarly compartmentalised. The golden age of genteel foreignness began. The well-off, the artistic, the bored, the adventurous went abroad. (The broad masses went too, as empires, steamships and railways made travel cheaper and easier.) Foreignness was a means of escape—physical, psychological and moral. In another country you could flee easy categorisation by your education, your work, your class, your family, your accent, your politics. You could reinvent yourself, if only in your own mind. You were not caught up in the mundanities of the place you inhabited, any more than you wanted to be. You did not vote for the government, its problems were not your problems. You were irresponsible. Irresponsibility might seem to moralists an unsatisfactory condition for an adult, but in practice it can be a huge relief. Writers in particular seemed to thrive in exile, real or self-imposed. The qualities of it— displacement, anxiety, disorientation, incongruity, melancholia—became the modern literary sensibility. A writer living overseas could shrug off the perceived limitations of country and culture. He was no longer an English author, or an Irish author, or a Russian author, he was simply an Author: think of James Joyce, Christopher Isherwood, Vladimir Nabokov, Samuel Beckett, Joseph Brodsky. It became, and remains, bad form to pigeonhole a writer by country. All want to be writers of the world, and the world rewards that aspiration. Of the past ten winners of the Nobel prize for literature, five (V.S. Naipaul, Gao Xingjian, J.M. Coetzee, Doris Lessing and Herta Müller) have been émigrés. An earlier Nobel prize-winner, Ernest Hemingway, set the ground rules for the writer as foreigner when he was part of the 1920s expatriate community in Paris: live in Saint-Germaindes-Prés (or equivalent), work in cafés, meet other artists, drink a lot. Not everyone can be Hemingway. Many foreigners today are threadbare students, overworked managers, trailing spouses. The male expatriate in Bangkok is a great deal freer than the female expatriate in Jeddah. The lot of unwilling foreigners is far worse still. A life of foreignness imposed by poverty or persecution or exile is unlikely to be enjoyable at all. Even so, all other things being equal, foreignness is intrinsically stimulating. Like a good game of bridge, the condition of being foreign engages the mind constantly without ever tiring it. John Lechte, an Australian professor of social theory, characterises foreignness as “an escape from the boredom and banality of the everyday”. The mundane becomes “super-real”, and experienced “with an intensity evocative of the events of a true biography”. An American child psychologist, Alison Gopnik, when reaching for an analogy to illuminate the world as experienced by a baby, compared it to Paris as experienced for the first time by an adult American: a pageant of novelty, colour, excitement. Reverse the analogy and you see that living in a foreign country can evoke many of the emotions of childhood: novelty, surprise, anxiety, relief, powerlessness, frustration, irresponsibility. It may be this sense of a return to childhood, consciously or not, that gives the pleasure of foreignness its edge of embarrassment. Narcissism may also play a part. While abroad, one imagines being missed by friends and enemies at home. Beneath it all there is the guilt of betrayal. To choose foreignness is an act of disloyalty to one’s native country. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 15 That idea of disloyalty is less bothersome now. But a century or so ago it was a mark of deviance for an English gentleman to admit the desirability of living anywhere other than England. The best argument in favour of spending time abroad was that it gave you a better appreciation of the virtues of home. “What should they know of England, who only England know?” wrote Kipling. I’m an alien Nowadays, you might rather say that the more you know of other countries, the more inclusive of all humanity your values will become. You educate yourself, beginning with anthropology. Every foreigner of inquiring mind becomes a part-time anthropologist, wondering and smiling at the new social rituals of his adoptive country. George Mikes, a Hungarian living in England, wrote a book in this genre called “How To Be An Alien”, published in 1946. It was not really about how to be an alien at all, but about a foreigner’s view of English society, and it was very funny. Mikes rightly saw that most social codes partook of the arbitrary and the absurd. If you happened to stand outside them, as a foreigner always did, then life could be a continuous comedy. Mikes wrote later, tongue in cheek, that he had expected his English friends to be very angry at the mocking portrait he painted of their country. Instead they seemed to enjoy it thoroughly. Mikes had been making fun of a culture confident enough to laugh at itself, and his underlying admiration and affection for it were clear. Still, it could have gone badly wrong. Foreigners do complain more than they should, and locals do not like it. If you were to write a book called “How To Be An Alien” today, and meant it to be a serious manual of instruction for use anywhere in the world, it might consist of three rules only. Pay your taxes, speak some English and be nice about the country where you live. Exaggeratedly nice. Avoid even trivial criticisms. You do not go into somebody’s house and start rearranging their furniture. Perhaps foreigners are, by their nature, hard to satisfy. A foreigner is, after all, someone who didn’t like his own country enough to stay there. Even so, the complaining foreigner poses something of a logical contradiction. He complains about the country in which he finds himself, yet he is there by choice. Why doesn’t he go home? The foreigner answers that question by thinking of himself as an exile—if not in a judicial sense then in a spiritual sense. Something within himself has driven him away from his homeland. He becomes even a touch jealous of the real exile. Life abroad is an adventure. How much greater might the adventure be, how much more intense the sense of foreignness, if there were no possibility of return? For the real exile, foreignness is not an adventure but a test of endurance. The Roman poet Ovid, banished to a dank corner of the empire, complained that exile was ruining him “as laid-up iron is rusted by scabrous corrosion/or a book in storage feasts boreworms”. Edward Said, a Jerusalem-born Palestinian-American scholar, caught the romance and pain of exile when he called it “a strangely compelling idea, but a terrible experience”. The true exile, he said, was somebody who could “return home neither in spirit nor in fact”, and whose achievements were “permanently undermined by the loss of something left behind for ever”. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 16 The willing foreigner is in exactly the reverse position, for a while at any rate. His enjoyment of life is intensified, not undermined, by the absence of a homeland. And the homeland is a place to which he could return at any time. Of pain and pleasure The funny thing is, with the passage of time, something does happen to long-term foreigners which makes them more like real exiles, and they do not like it at all. The homeland which they left behind changes. The culture, the politics and their old friends all change, die, forget them. They come to feel that they are foreigners even when visiting “home”. Jhumpa Lahiri, a Britishborn writer of Indian descent living in America, catches something of this in her novel, “The Namesake”. Ashima, who is an Indian émigré, compares the experience of foreignness to that of “a parenthesis in what had once been an ordinary life, only to discover that the previous life has vanished, replaced by something more complicated and demanding”. Beware, then: however well you carry it off, however much you enjoy it, there is a dangerous undertow to being a foreigner, even a genteel foreigner. Somewhere at the back of it all lurks homesickness, which metastasises over time into its incurable variant, nostalgia. And nostalgia has much in common with the Freudian idea of melancholia—a continuing, debilitating sense of loss, somewhere within which lies anger at the thing lost. It is not the possibility of returning home which feeds nostalgia, but the impossibility of it. Julia Kristeva, a Bulgarian-born intellectual resettled in France, has caught this sense of deprivation by comparing the experience of foreignness with the loss of a mother. But we cannot expect to have it all ways. Life is full of choices, and to choose one thing is to forgo another. The dilemma of foreignness comes down to one of liberty versus fraternity—the pleasures of freedom versus the pleasures of belonging. The homebody chooses the pleasures of belonging. The foreigner chooses the pleasures of freedom, and the pains that go with them. Reading 6: Economic crisis sabotages Russia’s efforts to halt falling population Russia’s efforts to put a brake on a falling population have been sabotaged by the economic crisis Sergei Balashov, 2009 Despite all the efforts Russia took to halt depopulation, the latest UN demographic report confirms that they have fallen short of the mark. As the decline of Russia’s population accelerates, the country is set to face overwhelming social and economic problems. But there are few if any obvious answers, prompting some policymakers to reach for ever more desperate solutions. The United Nations’ report on human resources development in Russia offered gloomy forecasts for Russia’s population, which the report claimed would decline by some 26m to 116m by 2050. The UN report has also warned that the rapid depopulation will bring dire economic К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 17 consequences. Russia has lost more than 12m people since depopulation started in 1992. This trend currently shows no signs of slowing down, and Russia will continue to lose people – the only question is: how quickly? An expert at the Russian Academy of Sciences Anatoly Vishnevsky painted an even gloomier picture, predicting a population of 98m for Russia in 2050. What is worse is that the problem affects Russia’s least populated and underdeveloped territories, particularly regions in the Far East and Siberia. Accounting for 36pc of Russia’s territory, the Far East is home to just 6.8m people. The Russian Committee for Statistics predicts that both Siberia and the Far East will each lose 11pc of population by 2025, while the number of central Russian inhabitants will go down by only 3pc. Even more troubling is that the number of able-bodied adults is declining faster than any other demographic category. This group is expected to absorb the bulk of the losses, declining by 14m by 2025. According to the RBC daily, in 16 years every 1,000 employed Russians are going to be providing for some 800 dependents. Due to the recent economic growth, these negative trends seemed to be slowly reversing over the past few years. Birth rates rose modestly thanks to increased stability, and the country became more appealing to foreign workers. Immigration was seen as a possible solution to Russia’s demographic problem, complementing the government’s increased efforts to boost birth rates and improve healthcare to fight high mortality. In 2007, there were more than 1.7m foreign workers in the country, a significant increase from a little over 1m in 2006. But then the financial crisis kicked in, greatly affecting the flow of labour into the country. The Federal Migration Service has already stated that labour migration declined by 27pc in the first quarter of this year. But despite the fact that it helped bring almost 6m people to the country, some experts believe that the role of migrants in combating depopulation is dubious. “There are two takes on migration: the first notion is that migrants will ruin the country,” said Sergei Ermakov, the head of the demographic programmes department at the Institute for Demography, Migration and Regional Development. “Everyone is afraid that Russia will get taken over by the Chinese, but that’s not going to happen. What is going to happen is that the only people to come here will be Caucasians and Middle Asians. But they will come and go; they will not assimilate simply because everything is too foreign for them over here”. “The second notion is that migrants will save us, but that’s also not true. State programmes to encourage Russians living outside of the country to move back have failed miserably and very few people are returning. You get maybe 10,000 per year via these programmes.” However, migration was not seen as the only way out of the demographic quagmire. In 2006 the government introduced benefits for large families. Starting in 2007, every woman bearing a second or any consecutive child could get maternity payments, a sum that has been gradually growing every year to more than $11,000 at its peak in mid-2008. However, this money came with a few strings attached. It could only be spent on the child’s education, paying off a mortgage or the mother’s pension. The ruling United Russia party has been particularly proud of this initiative, crediting then-president Vladimir Putin with inventing this attempt to boost birth rates. However, the UN experts claim that only 1pc of women who recently had children ascribed their decision to the financial benefits. This is because the problem of educational expenses does not come up until the child turns 16 or 17. Living conditions could also hardly be improved with this money, as even in post-crisis Moscow property costs more than $4,000 per square metre, plus raging inflation has already eaten up a good portion of the maternity bonus. Today, this sum К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 18 amounts to less than $9,000. A woman can also only claim the money for one child, no matter how many she has after bearing the first one. Even if this maternity capital worked, it still wouldn't be enough to recompense for the population losses. EU countries spend about 2.2pc2.4pc of the GDP to support large families, while in Russia state aid amounts to roughly 1pc. The one factor that should not be ignored is that the people’s attitude is also changing. Education and careers are the priorities now, and starting a family is often on the backburner, for women as much as for men. Various proposals have been championed to combat people’s unwillingness to have more children. Alexander Chuev, a State Duma deputy from the Just Russia party, has been campaigning for a reinstitution of the Soviet small-family tax, a 6pc income tax imposed on childless single men and married women, as well as couples that did not have children after one year of marriage. “The public should show more love for children, families with two or more children should get the most favourable treatment in this country,” said Evgeny Yuriev, the president of the ATON Capital Group and an expert on Russia’s demographics. “The government should adopt this attitude and act accordingly. The goal here is to change this mindset.” Ex. 11 Summarize the text making use of at least 8 words in bold type from the text. К.В.Малыхина. Английский для студентов IV курса факультета МО “Demography” 19