Business Policy with an Ignatian Twist

Submitted by Stephen J. Porth and W. Richard Sherman,

Saint Joseph’s University

5600 City Avenue

Philadelphia, PA 19131

sporth@sju.edu

rsherman@sju.edu

ABSTRACT

Business Policy is the capstone course in the curriculum of many business schools, Jesuit

and non-Jesuit alike. At Saint Joseph’s University, we have designed this course in a

unique way, with an eye toward our mission as a Jesuit school of business. In addition to

the fact that the course is four-credits and team-taught by faculty from four different

business departments, the framework of the strategic management process that underlies

the entire course is different from the standard model. Rather than use the maxim that the

purpose of a business is to maximize shareholder wealth, our capstone course is based

upon a nuanced version of the stakeholder model of management which emphasizes that

the purpose of business is not to maximize profits, shareholder wealth or anything else for

that matter, but to create value for a group of key stakeholders. The challenge of

strategic management is that each of these stakeholders places legitimate but sometimes

conflicting claims on the organization.

The purpose of this paper and presentation is to introduce some of the models and

frameworks used in the course which reflect the Jesuit mission of the business school.

The emphasis will be on the Jesuit imprint on the course, which is subtle but fundamental

to the understanding of strategic management as the course is designed. It is subtle in the

sense that traditional Jesuit ideals such as cura personalis, men and women for others,

and magis may never be explicitly mentioned during the course but are inherent in the

philosophical understanding of what it means to be a successful strategic manager. The

paper and presentation will identify and discuss how this is accomplished.

1

As it is taught at Saint Joseph’s University, Business Policy, the capstone course

for undergraduate business majors, is designed and delivered in a unique way. The

course is four credits and taught by a team of faculty from four departments –

management, accounting, finance and marketing. The textbook used for the course, now

in its second edition, was written specifically to support the course design and the Jesuit

mission of the business school in which it is taught. The purpose of this paper is to

emphasize a few of the “Ignatian” elements of the course and to present the models and

frameworks used to support that emphasis.

The Strategic Management Framework

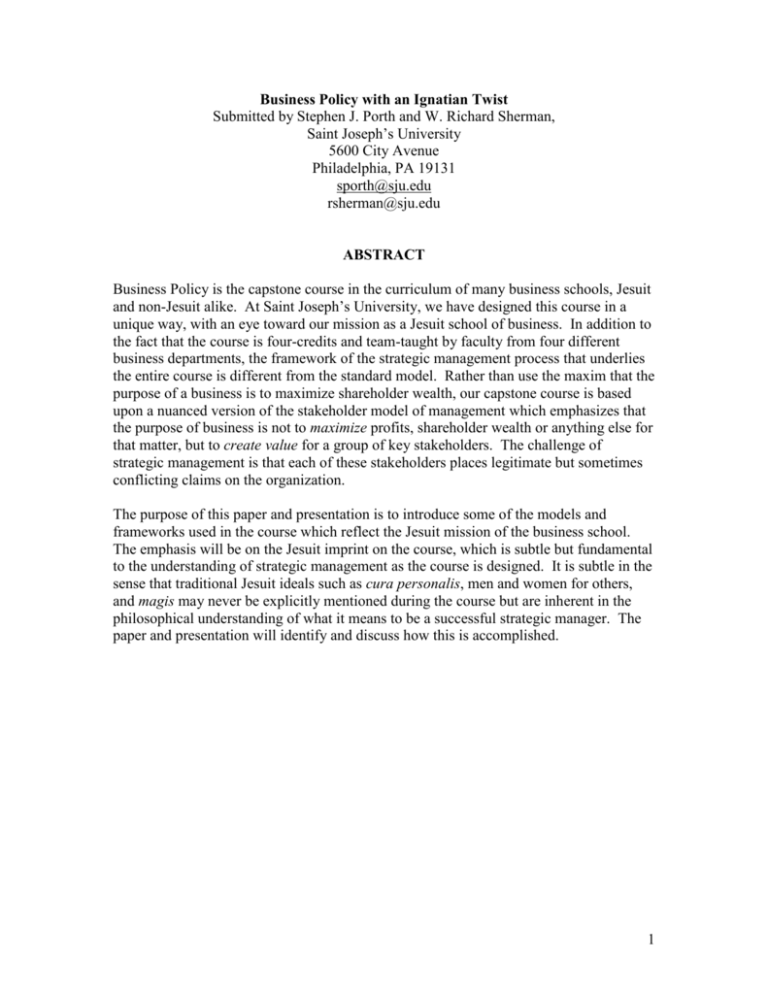

The fundamental purpose of strategic management as defined in our capstone

course differs from the standard model. Rather than use the maxim that the function of a

business is to maximize shareholder wealth, our capstone course is based upon a nuanced

version of the stakeholder model of management which emphasizes that the purpose of

business is not to maximize profits, shareholder wealth or anything else for that matter,

but to create value for a group of key stakeholders and to perpetuate the value-creating

capability of the organization over the long-term. The most prominent of these

stakeholders, and the ones that receive the most emphasis in the course, are customers,

employees and stockholders (or owners) – the C-E-O Model.

We begin by discussing what the concept of value is for each stakeholder group,

how that is measured, and how the types of value are interrelated. It becomes apparent to

students that each of these stakeholders, and others such as the local community, place a

legitimate claim on the company, and that these claims are sometimes mutually

supportive while at other times they clash. The challenge of strategic management then

2

is to manage these legitimate but sometimes conflicting claims on the organization so as

to sustain the long-term health of the organization. Figure 1 shown below is used

throughout the course to emphasize the imperative of value creation and its relationship

to the steps in the strategic management process.

Figure 1 - The Strategic Management Framework

Develop

Mission &

Vision

Perform

Situation

Analysis

Customers

Value

Creation

Employees

Owners

Set

Objectives

& Craft

Strategy

Implement

Strategy

Assess

Value

Creation &

Provide

Feedback

3

Ethical Analysis of Strategic Choice

As is normally the case, our emphasis in teaching the Business Policy course is

not just strategic analysis but analysis for a purpose – to make strategic choices. This

focus on decision-making means that students need to be adept at identifying strategic

issues facing a company. Strategic issues are the critical challenges, opportunities,

problems or questions the organization needs to address for the sake of its future. Once

the “right” issues are identified, students begin to consider their strategic choices. As part

of that decision-making process, students are challenged to consider the ethical

implications of the various possible strategies. We emphasize that these strategic choices

are subject to critical assessment through the use of various ethical frameworks,

including:

Utility view- it is ethical if it represents the greatest good for the greatest

number of people.

Rights view- it is ethical if it protects and respects basic human rights.

Justice view- it is ethical if it treats people fairly based on basic standards,

rules, and laws.

These ethical norms are in contrast to a norm of individualism that suggests an

action is ethical if it serves one’s own self-interests, and relativism which suggests that

there is no way to determine right from wrong since it all depends on the situation and

every situation is unique. Relativism and individualism are criticized because they

represent ways to justify almost any type of action or behavior.

The framework for ethical analysis below presents a three-stage process for

analyzing the ethical aspects of a strategic choice.

4

Figure 2 - A Framework for Ethical Analysis of Strategic Choice

Source: Adapted from Cavanagh, G. F. (2006). American Business Values : A Global

Perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

I

5

Before making a commitment to a strategic choice, managers need to assess the

ethical dimensions of the strategy. Does the strategy pass the ethics test? Some

companies ask themselves, “Will we be comfortable reading about ourselves and this

strategic choice in a front-page newspaper article?”

In stage one, the facts and evidence about the strategy are gathered. What is the

strategy, what resources will it consume, what stakeholders will it impact, what are its

intended and unintended consequences?

In stage two the strategy is analyzed according to various ethical frameworks and

moral principles described above. The utility analysis seeks to identify the various

stakeholders impacted by the strategy and the relative costs and benefits of the strategy

for each. The utilitarian approach emphasizes consequences and aims to assess the

aggregate welfare that the strategy produces. The better strategy is the one that produces

the most overall benefit for stakeholders. Some inherent problems with this approach

include the practical difficulty of predicting and measuring consequences of strategies

and the possibility that even a strategy that benefits many stakeholders can violate the

fundamental rights of a particular stakeholder.

To counteract these inherent problems, a rights-based analysis can be conducted.

This approach recognizes the basic rights of stakeholders such as respect for property

rights and personal dignity, and the duty of the organization to respect those rights. The

Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” is a rights-based

principle, emphasizing the norm that a decision or act is ethical if it results in

implications for others that you would not mind for yourself.

6

Similar to the rights approach, the justice approach evaluates the strategy based

on principles of fairness and justice. The justice approach might apply to issues such as

setting executive compensation versus workers salaries, equal opportunity for women and

minority candidates, sweat shops, and the question of a living wage. For example, is it

fair for supermarkets (or other retailers) to avoid impoverished neighborhoods? Do

companies, in this case, food retailers, have any obligations to serve consumers in poor

communities? If so, how are those obligations balanced against the obligation to be

profitable and create value for stockholders? Some companies are turning conventional

wisdom upside down and finding creative and profitable ways to serve the poor as

consumers. These strategies not only respect and promote the dignity of the poor but also

create value for stockholders.

The third and final stage of ethical analysis is to make a judgment as to whether

the strategic choice is ethical. Strategies that pass the ethics test are ready to be

considered for the next steps of the strategic management process.

The Balanced Scorecard

As previously noted, the Strategic Management Framework is used to analyze

value creation for ALL stakeholders, not merely the owners of the firm. Consequently,

traditional measures of maximizing stockholder (i.e., owner) value are inadequate.

Moreover, given the integrative nature of the Business Policy course – and of strategic

decisions themselves – financial measures alone will not suffice in evaluating the success

of strategic choices. The balanced scorecard (BSC) developed by Kaplan & Norton

(1996) provides a vehicle to broaden the scope of performance measurement. By its very

nature, it cuts across disciplines, turning functional silos on their sides. The BSC

7

approach allows finance and accounting to interface with marketing and production; it

not only facilitates but requires operations to work with organizational design. In short,

the BSC provides a comprehensive approach for considering the full impact of some

decisions while at the same time helping to solve smaller isolated problems that can more

readily be seen within its structure. It strikes “the balance between short- and long-term

objectives, between financial and non-financial measures, between lagging and leading

indicators, and between external and internal performance perspectives” (Kaplan &

Norton, 1996, p. viii). In the Business Policy course, the BSC provides a flexible,

integrative and more inclusive way of keeping score that addresses customer, employee

and other interests.

Figure 3 – The Balanced Scorecard

Financial:

(Past)

How do we look to our

owners?

Customer:

(Outside)

How do our

customers

see us?

Balanced

Scorecard

Internal:

(Inside)

At what business

processes must

we excel?

Learning & Growth:

(Future)

Can we continue to improve

& create value?

Employees

(Adapted from Kaplan & Norton, 1992, p. 72)

As the above diagram illustrates, the BSC explicitly addresses four value drivers

of organizational performance – financial, customer, internal, and learning & growth.

8

Another way of expressing the BSC is it views an organization through four different but

interrelated lenses - in terms of past performance, future potential, an outsider’s view, and

an insider’s perspective. Traditionally, decision-makers have focused primarily, if not

exclusively, on financial measures such as profitability, cash flow, sales growth and

return on equity to assess a company’s performance. However, such a focus fails to

capture the necessary interrelationships among the perspectives. In addition, the use of

financial measures alone does not and can not capture the value created by intangible

assets (measures in the Growth & Learning Perspective) which often create the

competitive advantage for a company (Kaplan & Norton, 2001; Lev, 2001). Furthermore,

disappointing financial results often stem from serious problems in core business

processes (i.e., measures in the Internal Perspective). Most critically, as one author notes,

using financial measures alone is like driving a car looking through the rear view mirror

(Niven, 2005).

The BSC creates metrics that drive value creation. Differing strategies dictate

what should be included in the scorecard. This is the beauty of the BSC. It can be adapted

and expanded to include metrics on leadership (Van De Vliet, 1997), supplier

relationships (Partridge & Perren, 1997), workforce diversity (Knouse & Stewart, 2003),

the strategic readiness of intangible assets (Kaplan & Norton, 2004a), community

investment (Kaplan & Norton, 2004b), and/or corporate social responsibility (Crawford

& Scaletta, 2005). Indeed, Kaplan & Norton (1996) suggest any stakeholder interest

which defines a business unit’s mission should be included in the BSC.

It is important to recognize the hierarchical nature of the traditional BSC. Kaplan

& Norton’s basic model assumes that financial performance is the ultimate goal of a

9

business (Bryant, Jones & Widener, 2004). However, the primacy of financial

performance and the interests of owners are not necessary assumptions in our Strategic

Management Framework. The interests of customers and employees as well as other

important stakeholders can and should be included in the BSC. For example, Van der

Woerd & van den Brink (2004) offer a modification of the traditional BSC. Set within the

European Corporate Sustainability Framework (ECSF), the “Responsive Business

Scorecard” (RBS) adds a fifth perspective to the traditional BSC.

Figure 4 – The Responsive Business Scorecard

The Responsive Business Scorecard

Customers

&

Suppliers

Financiers

&

Owners

Society

&

Planet

Internal

Processes

Employees

&

Learning

(Source: van der Woerd & van den Brink, 2004, p. 178).

Unlike the traditional BSC which emphasizes profit as the ultimate goal, “in a

RBS, People and Planet must become on equal footing with Profit” (van der Woerd &

van den Brink, 2004, p. 177). This is just one example of how the BSC can be modified

to support the C-E-O model of value creation in our Strategic Management Framework.

10

Conclusion

The Business Policy course is unique in several respects. While the standard

course at Saint Joseph’s meets for three hours per week (3 credits), Business Policy

carries four credits. Most courses in the undergraduate business program are taught by a

single faculty member, are housed in a particular academic department, a fact recognized

by the departmental prefix attached to the course (e.g. ACC 1011; FIN 1341; MGT 1011;

MKT 2031). Business Policy is team-taught by members from four departments. The

course carries a BUS prefix (BUS 2901) in recognition of the fact that this is not a course

that is housed in a particular department but is “owned” by the school of business as a

whole. It is designed and delivered as being a truly integrated capstone experience.

What further distinguishes Business Policy from the capstone courses at other

schools are the models and frameworks used in the course which reflect the Jesuit

mission of the business school. This paper has illustrated how the Strategic Management

Framework with its C-E-O model departs from the maxim that the purpose of a business

is to maximize shareholder wealth and instead focuses on value creation for a group of

key stakeholders. The challenge of strategic management is that each of these

stakeholders places legitimate but sometimes conflicting claims on the organization. The

use of an ethical framework for the analysis of strategic choice helps resolve some, but

not all of these potential conflicts. At the very least, it challenges our students to

explicitly consider the ethical implications of their “business” decisions. Finally, the use

of the Balanced Scorecard which highlights the cause-and-effect relationships among

11

employees, customers and owners provides a more inclusive way of measuring the

success of strategic choices.

The Jesuit imprint on the course is subtle but fundamental to the understanding of

strategic management. It is subtle in the sense that traditional Jesuit ideals such as cura

personalis, men and women for others, and magis may never be explicitly mentioned

during the course but are inherent in the philosophical understanding of what it means to

be a successful strategic manager.

12

References

Bryant, L., D.A. Jones & S.K. Widener (2004). Managing value creation within the firm:

An examination of multiple performance measures. Journal of Management

Accounting Research. 16:106-131.

Cavanagh, G. F. (2006). American Business Values : A Global Perspective (5th ed.).

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Crawford, D. & T. Scaletta (2005). The balanced scorecard and corporate social

responsibility: Aligning values for profit. CMA Management (October 2005):

20-27.

Kaplan, R.S. & D.P. Norton (1992). The balanced scorecard: measures that drive

performance. Harvard Business Review (Jan-Feb 1992): 71-79.

Kaplan, R.S. & D.P. Norton (1996). The balanced scorecard: translating strategy into

action. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Kaplan, R.S. & D.P. Norton (2001). The strategy-focused organization: How balanced

scorecard companies thrive in the new business environment. Boston, Mass.:

Harvard Business School Press.

Kaplan, R.S. & D.P. Norton (2001). Transforming the balanced scorecard from

performance measurement to strategic management: Part 1. Accounting Horizons

15(1): 87-104.

Kaplan, R.S. & D.P. Norton (2004a). Measuring the strategic readiness of intangible

assets. Harvard Business Review (Feb 2004): 52-63.

Kaplan, R.S. & D.P. Norton (2004b). Keeping score on community investment. Leader to

Leader (Summer 2004) 33: 13-19.

Knouse, S. B. & J.B. Stewart (2003). “Hard” measures that support the business case for

diversity: A balanced scorecard approach. Overcoming Barriers to Opportunity

11(4): 5-10.

Lev, B. (2001). Intangibles: Management, Measurement, and Reporting. Washington

DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Niven, P.R. (2005). Driving focus and alignment with the balanced scorecard. The

Journal for Quality & Participation (Winter 2005): 21-43.

13

Partridge, M. & L. Perren (1997). Winning ways with a balanced scorecard. Accountancy

120: 50-51.

Van de Vliet, A. (1997). A new balancing act. Management Today: 78-80.

Van der Woerd, Frans & Timo van den Brink (2004). Feasibility of a responsive business

scorecard – a pilot study. Journal of Business Ethics 55: 173-186.

14