Document 7687111

advertisement

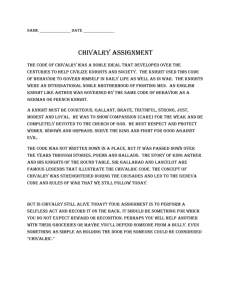

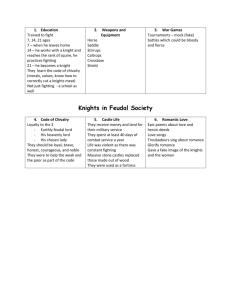

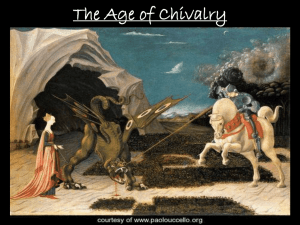

CHIVALRY Before embarking on any historical pathway a pause to consider the subject in terms of the modern world might be considered a reasonable approach, and so the student might turn to a C20th century Oxford Dictionary which defined Chivalry thus : horsemen, cavalry (archaic); knightly skill (archaic); medieval knightly system with its religious, moral and social code; ideal knight’s characteristics; devotion to the service of women; inclination to defend weaker party; gallant gentlemen. Another dictionary yielded similar results, which reinforced the possibility of variations of conduct over time, a proposition that might well bear scrutiny. Chivalry is normally associated with nobility of soul or spirit and largely attributed to princes, from which height it filtered down through nobles to knights and, in due course to esquires or gentlemen of repute. Its history evolved from a period when the barbarian tribes who had broken through the Roman Empire’s defences, began to settle. Order had ultimately to be established and, in most western areas, this would lead to the creation of some kind of feudal system, with an emperor, a king, a prince, an earl or a count exercising control in their specific area, and paying homage to an overlord. The system demanded a strong man at the top and, if this condition did not obtain, there was anarchy that might be tempered only by the intervention of the Church – a universal Catholic Church that had eliminated all rivals and which could offer moral guidance. It first sought to protect non-combatants in a dispute by a proclamation of a “Truce of God”(end of C10th) and later (c. 1040) established a “Peace of God” proposing that no engagements would be undertaken between Thursday night and Monday morning. The foremost power in Western Europe had been the Empire of Charlemagne, whose nobles were to be attributed as authors of the first Code of Chivalry, culled from the Song of Roland and which might be seen to set the pattern of the ideal to be fostered in the feudal chivalry period. The accent would be upon : the promotion of the Church, of liege lord, of honour and glory, to keep faith, to tell truth, to respect women, never to turn a back upon a foe, never to refuse a challenge from an equal, to obey authority, to protect the weak, the defenceless, widows and orphans – noble aspirations which set the target for the C11th warrior – in essence a military code of honour, that could appreciate the idea of the Just War, and nothing could be more just than to fight for the Faith against the Saracens, who had captured the Holy City. The First Crusade, inaugurated by Pope Urban II brought new attitudes towards the protection of the property of volunteers who marched to the East ; some made enormous sacrifices, others sought advantage, but for most the prospect of honour, even of salvation, loomed large – a mighty chivalrous enterprise was born. The holy city of Jerusalem was rescued, as were Edessa and Antioch en route and a Kingdom and Principalities were established that gained the overall title of Outremer. 2 It should not be forgotten that, before this success, Moslem states in the Mediterranean had been seized by Norman knights and the Reconquista from the Moors had begun in the Iberian peninsula. A universal struggle had opened up and, among the problems that arose perennially was the defence of peaceful pilgrims (palmers), an endeavour enthusiastically encouraged by the Church, out of which emerged the Religious Orders of Knighthood – the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitallers, both systematically to erect those magnificent castles. Later the Teutonic Order was established and in the peninsula were created the great orders of Santiago, Calatrava and Alcantara. It took until 1492 for the total elimination of the Moorish Kingdom, the final war for Granada producing many chivalric figures, immortalised by Washingon Irving. The Crusader states in Outremer did not last as long. Commerce with the Moslem world was not all blood and thunder. There was an inevitable attraction to certain aspects of Eastern life that were to permeate Western society. Contact with the peninsula, where, through expansive libraries, the learning of people like Avicenna spread and where Moorish romanceros or ballads telling of the love of sturdy knights and attractive ladies were celebrated, often accompanied by tambourists. The most important connection with these new influences was to be the Languedoc, Acquitaine Provence, where William IX Duke of Acquitaine and Count of Poitiers set in motion a fresh exciting environment. An unsuccessful Crusader, a more successful ladies’ man, who achieved lasting celebration as a troubadour, producing verse in the manner of the Moors and setting a standard for his fellow minstrels. Even more famous was his parenthood of the dazzling and adventurous Eleanor of Acquitaine, destined to become first Queen of France and later of England. Her court was to become a base for troubadours, chivalry and courtly love, although more credit for the latter innovation might be given to her daughter, Marie of Champagne, who became the patron of Andreas Capellianus, author of “The Art of Courtly Love”, which laid down rules for this preoccupation which included :marriage was no excuse for not loving; no one should be deprived of love without reason; love should not be made public; love should be difficult to obtain; lovers should be apprehensive; a true lover, in everything he does, should always be thinking of his beloved. Similar sentiments punctuate the “Romance of the Rose” celebrating the search for love. 3 These developments, allied to the older ideals of chivalry , meant that the goal-posts were being moved and it was another protégé of Marie who initiated the appropriate vehicle – Chretien de Troyes, who translated the “Ars Amoris” of Roman Ovid and applied its lessons to his early Romances, which could contribute to decisions made in the “Court of Love” Marie has established. The impetus to write of love stemmed from Moorish contact and a gentle sweet love between couples was reflected in early tales like “Aucassin and Nicolette” and “”Floris and Blanchfleur” which, in themselves, softened the early rougher Chanson de Geste concepts of the ideal knight, What Chretien was to do was to take up the Arthurian banner which had been planted in the Provencal court through Wace (who translated into French Geoffrey of Monmouth), but new prominent knights took centre stage, the most famous of whom was to be Lancelot, who would undergo even disgrace to serve his lady, who happened to be Guenevere, the wife of Arthur. As an always victorious knight, embewed with that concept of courtly love, Lancelot became the model for a new chivalry. More romances followed, often spread by trouveres, the Northern version of the troubadour, and, yes when the Germans took up the French model “minnesingers”. The Arthurian thread took further strength from longer romances like the Book of Lancelot, part of a formidable series that became known as the Lancelot-Grail or Vulgate cycle. This, among others, would be welded by Sir Thomas Malory into his seminal work. So was engendered a world of knights on horseback, in glittering armour, behind emblazoned shields, jousting in the lists, avoiding the rough and tumble of the old primitive melee, wearing ladies’ favours, fulfilling the vow of their predecessors, along with the precepts of courtly love. Not every husband appreciated this new order, with occasional slaughter of both errant spouse and lover. The involvement of queens was to disappear from the romances when, in 1314, at the Tower of Nesle, three princesses allied to the royal family of France were taken and charged with adultery, the ladies being confined and their knightly lovers destroyed. Notwithstanding these occasional blips, the kings and princes of Western Europe began to vie with each other for the honour of ruling the most celebrated court. Gentler attitudes had been further advanced by the growth of a cult of Mariolatry , the worship of the most ideal woman, a reinforcement of the prevailing secular attitudes. 4 The apogee, and probably the nadir, of this new chivalry came with the Hundred Year’s War, when a golden age emerged with Edward III, who, with his sons, principally young Edward, the Black Prince, as father and son could hold the lists against all comers. Arthuriana held sway; jousts became very elaborate affairs; a Round Table was constructed; Edward bowed to the solicitude espoused by his wife Phillipa at Calais; the Order of the Garter was established with its motto “ Honi soi qui mal y pense”, a phrase that might well adorn a Court of Love. What a galaxy of knights would grace the field of battle and the courts of kings, so many who might be accorded the title, ”Flower of Chivalry”, as the Chronicles of Froissart would aver; his choice would be the Black Prince, sullied only by his sack of Limoges and, perhaps, of supporting Pedro the Cruel. Contempories would give the laurel to Sir John Chandos on the English side, Bertrand du Guesclin on the French, both notably chivalrous in the affairs of ransom and its payment. There were many others of note, mainly becoming, in peace or truce, Captains of roving Companies who often had difficulties controlling their troops. One noble lord had associations in both camps, which he maintained with honour, a French hostage who married Isabella of England, knight of the Garter, supporter of the French king – Enguerrand of Coucy, the hero chosen by Barbara Tuchman in “A Distant Mirror”, one who died a prisoner after his valiant participation in the “final crusade” of Nicopolis, where also fought Jean Sans Peur, a future Duke of Burgundy. There was also a dark, brutal side to Western conflict – jousting gave way to the barbarous melee, making for bloody encounters like the Battle of the Thirty. The Treaty of Bretigny, the intervention of the Black Death , the subsequent diminution of the labour market, the growing senility of Edward III made for a hiatus in hostilities, during which that Bertrand du Guesclin had slowly retrieved for France a large part of the territory Edward had won . English honour was revived when Henry V came to the throne, fought an Agincourt and won back even more of France. His early death left a minor (Henry VI) as king and divisions among the nobility resulted, and these contributed to a downward spiral of English success in France, a success that had originally been supported by Philip, the Duke of Burgundy, the son of that Jean Sans Peur, who had been treacherously assassinated on the 10th September 1419 on the bridge of Montereau-fault-Yonne, a salient marker in the decline of chivalry, an affront that tarnished the name of Tanneguy du Chastel. Philip the Good held court in magnificent fashion, keeping alive the spirit of chivalry, but France had become a land where bands of armed warriors plagued its citizenship, the routers, flayers, eschorciers of the Chronicles of Enguerrand de Montstrelet. 5 Some of these bands could be coerced into reliable action under the leadership of men like La Hire and Pothon de Xaintrailles, who brought their ruffians to the side of La Pucelle and Dunois, sowing the seeds of a French revival where men of all quality joined to expel the English, whose nobles were to be left with no enemies but their own kind, in a land governed by rival parties seeking to influence a weak king. So began the Wars of the Roses. The nobles who supported the House of York or the House of Lancaster at first seemed on the surface to be keeping up old manners, the initial argument placed symbolically in a rose garden, but when serious battle commenced, old concepts like capture and ransom gave way to assassinations in the field. The countryside could be devastated as much by liveried retainers as had France by the Routiers, both bringing discredit to the world of chivalry. Some show of splendour, possibly encouraged by the advent of Caxton and the printing press, had graced the reign of Henry VI , and Edward IV sought to bring to life an Arthurian glory, but treachery, severity and hatred permeated the scene. Edward sought to pacify the situation and exercise control of the state, but intrigue was to go underground, to surface in the reign of his successor, who had little time to prove his worth before his ultimate betrayal, the ultimate betrayal, through desertion in the field. Chivalry seemed to have come to an end. There had been a constellation of noble minded men gathered around the Maid of Orleans, none more so than Gilles de Retz, who has gone down in history as the original Bluebeard, a mass murderer of children, who saw their blood as the elixir of youth, a descent to infamy. Yet, at the same time, on the plains of Italy could be found the Great Captain, Gonsalvo de Cordoba, and, among his opponents, one Pierre Terrail, Seigneur de Bayard, ” le chevalier sans peur et sans reproche”, and other courteous knights emerging from the conflict between France and Spain in the Kingdom of Naples. Times were changing – the Renaissance was developing – authors like Castiglione wrote “The Courtier”, influencing princes beneficially, where, perhaps, Machiavelli may have, in some cases, been a counter weight. A new Romantic influence, deriving from Boiardo, Ariosto and their like filled the air. There would be magnificence like the Field of the Cloth of Gold, and heroism in the Elizabethan period. Again, a galaxy of nobles assembled, of whom perhaps the most famous was Sir Philip Sidney, celebrated for his behaviour as he lay dying at Zutphen. Arthurian ideals sprang forward once more in the court of Gloriana, wooed by Prince Arthure, as we learn from Edmund Spencer in his “Faerie Queene”, where also are related the adventures of Calidore, the Knight of Courtesy. 6 The early Stuarts spent too much time proclaiming their Divine Right and arguing with parliament, a measure of how state control was developing – it ended in civil strife, when bright stars sometimes shone. Charles I’s followers, the cavaliers, had all the apparel and appeal of an older order, led by the dashing, ever over-enthusiastic Prince Rupert, but the man who emerged from this sorry business with the finest character was Lucius Cary, Lord Falkland, a principled young man who reluctantly went to war, a former Parliamentarian who supported the King, meeting his death on the field at Newbury. We cannot ascribe chivalry to men who beheaded their king, but Romance had its hero – the gallant Marquis of Montrose, one of the few people who could lead wild highlanders into battle. A namesake, Bonnie Dundee was to achieve the same feat, winning and dying at Killiecrankie, and a third such adventurer was to be Bonnie Prince Charlie – a trio who lent colour to the affairs of Scotland. The Restoration had witnessed a resumption of the cavalier spirit. England became involved in wars as an ally of Louis XIV and, in one campaign, ”le bel Anglais”, John Churchill, distinguished himself, fighting in the army of the Great Turenne at the siege of Maestricht, before which city was to fall the Chevalier Claude de Batz de Castelmar D’Artagnan, captain of the Grey Musketeers. That young Churchill would become Marlborough, who destroyed the armies of Louis in more or less courteous battles until the blood bath of Malplaquet, following which all yearned for peace. Different kinds of war followed, wars of manoeuvre , sustaining lesser losses. Some chivalry held the field as the commanders of opposing (French and English) Guards regiments could offer each other the advantage of firing the first shots at Fontenoy. Napoleon would put paid to such rubbish – he was an artillery man, fond of a whiff of grapeshot. Colour returned to the war with such cavalry leaders as Murat and Lannes, and most of Napoleon’s Marshals were, in their way, men of good behaviour in combat. But the world had changed ; industrialisation had brought heavy metal to the fore, and barbed wire and machine guns would ultimately cut down both cavalry and infantry. The knight in shining armour had validity no more, apart from the sacrifices of some gallant gentlemen. There had been an overall decline, but manners and courtesy could proliferate within in a more enfranchised society. The Captains and the Kings departed about 1919. Rigorous isms and ologies became the order of the day It would be only on a personal level that some form of chivalry could coexist, and, today the virtues might be: holding the door to house or car open for a lady, walking on the outside of the pavement for a lady, and similar courteous actions. Sadly, today, such efforts may go unnoticed or unappreciated, or worse.