Social, Political, and Military History of Ancient Egypt

advertisement

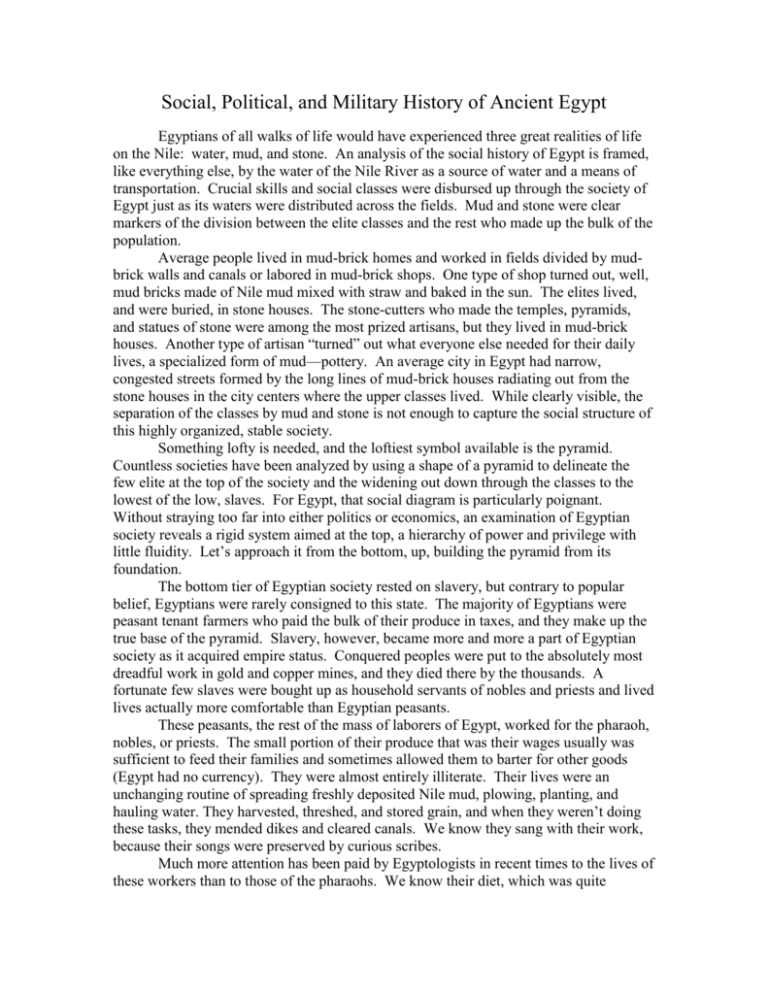

Social, Political, and Military History of Ancient Egypt Egyptians of all walks of life would have experienced three great realities of life on the Nile: water, mud, and stone. An analysis of the social history of Egypt is framed, like everything else, by the water of the Nile River as a source of water and a means of transportation. Crucial skills and social classes were disbursed up through the society of Egypt just as its waters were distributed across the fields. Mud and stone were clear markers of the division between the elite classes and the rest who made up the bulk of the population. Average people lived in mud-brick homes and worked in fields divided by mudbrick walls and canals or labored in mud-brick shops. One type of shop turned out, well, mud bricks made of Nile mud mixed with straw and baked in the sun. The elites lived, and were buried, in stone houses. The stone-cutters who made the temples, pyramids, and statues of stone were among the most prized artisans, but they lived in mud-brick houses. Another type of artisan “turned” out what everyone else needed for their daily lives, a specialized form of mud—pottery. An average city in Egypt had narrow, congested streets formed by the long lines of mud-brick houses radiating out from the stone houses in the city centers where the upper classes lived. While clearly visible, the separation of the classes by mud and stone is not enough to capture the social structure of this highly organized, stable society. Something lofty is needed, and the loftiest symbol available is the pyramid. Countless societies have been analyzed by using a shape of a pyramid to delineate the few elite at the top of the society and the widening out down through the classes to the lowest of the low, slaves. For Egypt, that social diagram is particularly poignant. Without straying too far into either politics or economics, an examination of Egyptian society reveals a rigid system aimed at the top, a hierarchy of power and privilege with little fluidity. Let’s approach it from the bottom, up, building the pyramid from its foundation. The bottom tier of Egyptian society rested on slavery, but contrary to popular belief, Egyptians were rarely consigned to this state. The majority of Egyptians were peasant tenant farmers who paid the bulk of their produce in taxes, and they make up the true base of the pyramid. Slavery, however, became more and more a part of Egyptian society as it acquired empire status. Conquered peoples were put to the absolutely most dreadful work in gold and copper mines, and they died there by the thousands. A fortunate few slaves were bought up as household servants of nobles and priests and lived lives actually more comfortable than Egyptian peasants. These peasants, the rest of the mass of laborers of Egypt, worked for the pharaoh, nobles, or priests. The small portion of their produce that was their wages usually was sufficient to feed their families and sometimes allowed them to barter for other goods (Egypt had no currency). They were almost entirely illiterate. Their lives were an unchanging routine of spreading freshly deposited Nile mud, plowing, planting, and hauling water. They harvested, threshed, and stored grain, and when they weren’t doing these tasks, they mended dikes and cleared canals. We know they sang with their work, because their songs were preserved by curious scribes. Much more attention has been paid by Egyptologists in recent times to the lives of these workers than to those of the pharaohs. We know their diet, which was quite healthful. Beans, lentils, wheat, and barley made up the staple diet. The wheat was consumed in the form of bread (the Egyptian word for life means “to have bread”), and the barley was converted into a soupy beer that was low in alcohol content and slurped by every age at every meal. Flavor and vitamins were provided by leeks, onions, lettuce, garlic and cucumbers. Delicacies included dates, pomegranates, melons, figs, honey, and cheese. The meat of pigs, sheep, goats, fish, and fowl provided added protein, and the Egyptians also raised donkeys and cows as draft animals. Beef was reserved for the upper classes. We know even more about the lives of artisans in the next tier of Egyptian society. We have unearthed whole cities of workers placed near their tasks. Towns existed at the foot of the pyramids and beside the Valley of the Kings. Piles of pottery shards and even fragments of papyrus have been discovered at these sites that were the discarded bills and orders of these important communities. Since we have been able to read their “Post-it” notes and receipt books, we know there were draftsmen, quarrymen, masons, carpenters, bricklayers, sculptors, painters, goldsmiths, jewelers, weavers, cabinetmakers, chariot makers, armorers, leather workers, and boat builders. All of these workmen were in the employ of the pharaoh and of the priests who paid in grain. Or sometimes, they didn’t get paid and therefore Egypt has claim to another first, the 1170 BC first recorded strike in history. It worked, too. One important aspect of this level of Egyptian society is almost entirely unique among ancient cultures. Egyptian women gained legal equality in 2700 BC. Women acquired particular skill in spinning and weaving of linen producing some of the finest quality textiles ever, some as sheer and soft as silk. By the way, ancient Egyptians raised flax, not cotton. Women made sandals, baskets, and the make-up that both sexes used, partly to deaden the glare of the sun. They made wigs. They made music. With so many female deities in Egyptian religion, women played a key role in Egyptian society. The next level up the pyramid consisted of the scribes who had to keep the records to organize all this activity. Bright boys from all classes were sent to schools where the one rule was, “a youngster’s ear is on his back—he listens when he is beaten.” The only other way to rise in Egyptian society was in the army, and that not until the New Kingdom when a professional army was permitted to exist. Two ranks of society made up the true elites. First, the priests owned land and slaves, commissioned the construction of temple complexes, and assisted the pharaoh in all his religious duties. They collected taxes for their gods. At times, they grew so rich that pharaohs had to intervene to keep them in their place. Above the priests, various ranks of nobles governed the 40 provinces of Egypt. As Egypt expanded, the pharaoh delegated civil power to the nobles which quickly turned into hereditary rights. One nobleman rose above the rest to become the pharaoh’s most trusted servant, the vizier. The pinnacle of the pyramid of society was occupied by one god-man, the pharaoh, and it is to the exploits of these religiously, economically, and politically all-powerful men (and one woman) that we must turn our study to summarize the political and military history of 3,500 years. An amazing archaeological discovery allows us to know the names of nearly every one. On a temple wall, a chart was inscribed bearing the names of every pharaoh from the first to Seti, the father of Ramses the Great. This stunning record of two thousand years of Egyptian history is the basis for the following chart historians have created to organize those records and all that followed: Old Kingdom 1st Transition Middle Kingdom 2nd Transition New Kingdom Late Transition 4,000 BC-3335 BC 3335 BC-3005 BC 3005 BC-2112 BC 2112 BC-1738 BC 1738 BC-1102 BC 1102 BC-525 BC Dynasties 1-6 Dynasties 7-10 Dynasties 11-13 Dynasties 14-16 Dynasties 17-20 Dynasties 21-26 To understand this brief overview, be aware first that the dates are all circa. Each of the three “kingdoms” marks a flowering of Egyptian civilization prompted by the accomplishments of a few great individuals. The transition periods were times of catastrophe, strife, famine, disease, or a combination of all of these that clouded history and created few records. It’s rather amazing to note that the entire history of the United States of America could be swallowed up in either of a couple of those time periods. The word “dynasty” refers to a series of rulers all related to each other by blood. New dynasties began when an old dynasty failed to produce a viable descendant as pharaoh, and some other family rose because of great feats in the ensuing crisis. The written name of a pharaoh was designated in Egyptian records by enclosing the hieroglyphs that made up the name in an oval called a cartouche. The first cartouche to appear on that temple wall contained the name of Pharaoh Menes, the founder of the first dynasty and the first king to rule a united Egypt. He began as a warrior who turned into a general who became the king of Upper Egypt. He marched his armies downstream and built a canal and diverted the Nile River with a mound that became the building site for his capital of Memphis. That must have been impressive to all Egyptians! A stone tablet (a copy of which is in the McClung Museum on the UTK campus) depicts Menes, wearing the crown of Upper Egypt denoted by a vulture, victorious over 7,000 men of the North, or Lower Egypt. The other side of the tablet shows Menes sacrificing 10 victims to celebrate. He and the decapitated bodies are pictured, but this time he is wearing the crown of Lower Egypt which bears a cobra. From that point on, pharaohs wore a single crown with both symbols on top together. The rest of the first and second dynasties were concerned with securing an adequate supply of copper, since this was the opening of the Bronze Age. This metallurgical feat led to military superiority, one war ending with the massacre of 47,209 of the enemy. By the end of the second dynasty, trade was opened up with Indo-European peoples in the region of the Black Sea. The third dynasty began with the achievements of Pharaohs Zoser and Snefru. Zoser is the pharaoh responsible for the step pyramid at Saqqara mentioned in the film, the first building of hewn stone in the world. He also is said to have loved literature. Snefru’s pyramids were not as immense as the Great Pyramid of Cheops which came later, but they are said to be the finest quality pyramids ever built. Sun worship among the upper classes accompanied the construction of pyramids, so while the population of Egypt viewed Amon as their chief deity, the elite cherished Re for themselves. In addition to building two pyramids, Snefru built a trading fleet of ships averaging 167 feet in length. This part is his greatest contribution. Having secured peace, he encouraged trade. Trade increased wealth, which provided the funding for art. Watch for that dynamic throughout the rest of our course regardless of what civilization we are studying. Priests, though, also benefited from greater societal wealth, and they purchased land. Over time, they became corrupt. Watch for that dynamic later, too. The fourth dynasty in Egyptian history was begun when Khufu, or Cheops, decided the priests had become too powerful and shut up their temples and forbade sacrifices to the gods. Egypt was perhaps so relieved at this lifting of a burden that they shouldered another one, the construction of the Great Pyramid, the monument and tomb of Cheops. I will wait for a look at the technology and economy of Egypt to better explain this feat later, but suffice it to say that if pharaohs were not viewed as gods before this massive public-works project was accomplished, they were ever after. The fifth and sixth dynasties are a succession of absolute rulers thought to be divine. The seventh dynasty brings up the problem, however, of the transition periods. History is nearly silent for 330 years during this first transition. A cause can be surmised from a look at the last ruler of the sixth dynasty, Pepy II. He assumed the throne at the age of ten and reigned 90 years. The civilization of Egypt was so dependent on the pharaoh that if the present pharaoh became sick, or in some instances merely lazy, the entire nation suffered and began to unravel. As Pepy II aged, the Syrians attacked, civil war erupted, and Egypt went into decline. Here was the chance for a new dynasty, the 7th, but problems seemed so severe that recording history was not a priority. Archaeologists find these historical moments by digging down to levels in the ruins of cities where the rocks show burn marks and there are lots of bodies strewn around unburied. Watch for that dynamic in all history, too. The Middle Kingdom marks the rise of several powerful generals who solidified central control over a growing class of governors and nobles who had gained power in the uncertainty of the 1st transition period. Middle Kingdom dynasties consisted of several Senuserts and Amonemhats who enlarged trade, built lesser pyramids, and then collapsed under the invasion and occupation of an illiterate people known as the Hyksos. This Egyptian name means, “shepherd-kings.” This title, the fact that the Hyksos were a Semitic people, and recentlydiscovered archaeological evidence have given rise to a theory that the Hyksos were actually the Hebrews who are said in their own history to have moved to Egypt in a famine and then become a controlling influence in the nation. Regardless of their true identity, the Hyksos ruled Egypt for centuries through the 2nd transition period. Illiterate peoples leave no written historical records, and little more is known. A fascinating story marks the beginning of the New Kingdom. Egyptian records say that the Prince of Thebes, an Egyptian puppet governor, got an interesting complaint. Hippopotami were keeping Apophis, the Hyksos king awake at night with their bellowing. Seqenen-Re III, the Prince of Thebes, knew he couldn’t control the bellowing of hippopotami, so he assumed Apophis was just making an excuse for an attack and decided to attack first. Seqenen-Re III pushed the Hyksos north before being killed in battle. His son, Aahmes, finally broke the Hyksos control of Egypt and established the New Kingdom. Ahmose’s son, Amonhotep organized Egypt to defend their independence, which his son, Thothmose, succeeded in doing. The presence of “mose” in the names of these rulers of Egypt makes up part of the theory that they were in the line from which Moses derived his name as an adopted prince of Egypt, if the Hyksos were the Hebrews. Also curious is the attempt by the next New Kingdom king, Akhenaten to establish monotheism in Egypt. He tried to impose the worship of only Aten over Re, Amon, etc. on Egypt, but the name of a boy-king successor reveals that he was unsuccessful. Tut-Ankh-Amon, or Tutankhamen, shows that King Tut brought back the traditional polytheistic worship with favoritism toward Amon. Perhaps it is in the aftermath of the defeat of the Hyksos, if they are the Hebrews, that they became enslaved in Egypt. At any rate, the Old Testament names the pharaoh from which they fled, Ramses, who is the most famous of all the New Kingdom rulers. The film revealed that Ramses the Great built more than any other pharaoh in all of Egypt’s history, and it is likely that he also fathered the most children (80-100). If he sparred with Moses and lost, he made war on the Hittites for twenty years and is responsible for yet another first for the world being Egyptian. He negotiated the first international peace treaty with the Hittites and made peace with them for the rest of his 64 years as pharaoh. Peace, remember, permits trade to build wealth, and Ramses needed wealth to leave all those stone images of himself with all of his wives represented as knee-high statues at his feet—so much for equality for women! Egypt declined, then, through a series of weak rulers, although one in this late period, Sheshank I, captured Jerusalem and stuck it to the Hebrews by robbing Solomon’s temple. The ignominious end to the chart of ancient Egyptian history, however, ends with the phrases, “Absorbed by the Persians, then by Alexander the Great, then by Rome.” Remember, however, when you sit at a four-legged table aboard a sailboat and record in ink on paper your personal history of the first day you shaved, or wore make-up, or studied astronomy or physics or engineering or . . .thank Egypt.