Interpreter in the language analysis interview

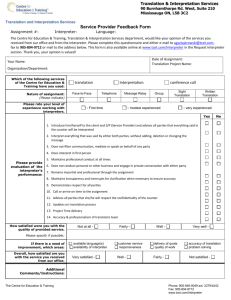

advertisement