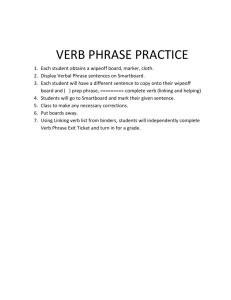

THE MERNYANG VERB PHRASE

advertisement