the english language and the use of english texts

advertisement

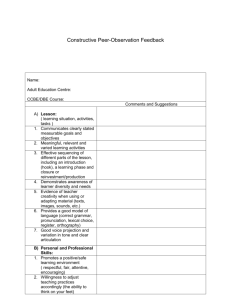

THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND THE USE OF ENGLISH TEXTS IN THE NIGERIAN UNIVERSITIES: A CASE OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS? By DR. S.T. BABATUNDE Department of English, University of Ilorin, Ilorin ABSTRACT The status of the English language in Nigeria has not engendered a commensurate development of the language, especially in the school system. That the youths, especially, do not have adequate functional competence in the language is attested to by the rate of failure in the terminal senior secondary school examinations and the low level of performance in the General English/Use of English programmes in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria, to mention just two instances. This study therefore investigates the potential contributions of materials to the maximum involvement of the learners in the English language programmes. The study evaluates the Use of English (USE) textbooks in eight randomly selected tertiary institutions in Nigeria with a view to determining the extent to which the textbooks are designed to enhance the involvement of the learners in the USE programmes. It was thus revealed that the learner-centredness concern of the texts is very remote. The goals of the materials appear to be subject and money-centred, rather than exposing the learners to the relevant language skills that should facilitate their studies in the institutions. The paper therefore suggests a more learner-centred and humanistic ‘USE’ materials so that adequate learning tasks and activities will be available for the learners to be maximally involved in the Use of English programmes, thereby ensuring that they are adequately equipped with the English language skills for their courses and professions. BACKGROUND The status of the English language in the higher institutions in Nigeria as the language of instruction, and that of the Use of English as a service course needs no further enunciation. However, the low level of competence demonstrated by the students in and out of school continues to draw attention to the ineffectiveness and the inefficiency in the presentation of this all important service course in the higher institutions in Nigeria. This situation compels various stake holders, especially experts in this case, to keep asking such questions that will continue to draw attention to the irregularities in the presentation of the Use of English (USE) or the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) programme in the higher institutions. Questions such as the following are pertinent: 1. What do USE teachers do with their students? 2. What do the learners do with USE? 3. What are the real goals of USE teaching in EAP? 1 4. 5. 6. What should be the goals and how can the goals be achieved? What are the factors influencing curriculum planning? What are the humanist and affective ends in the supposed communicative teaching of USE in the institutions? 7. What are the real sources of input for the learners in the USE class (teachers, course books, other students, etc)? 8. What is the extent of intake from the available input? Or to what extent are the learners able to have intake from the input sources? It is possible to examine most, if not all of these questions by asking the following question: What is the context of teaching USE/EAP in the higher institutions in Nigeria? Babatunde (2001:1-9) examines the context of teaching USE courses in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Using a model which presents the contextual factors as a semiotic wheel, (see figure 1), Babatunde submits that the socio-cultural, psychological, linguistic, educational, infrastructural and administrative contexts of teaching USE are not utilized effectively. He concludes that, The percentage of failure recorded every year in the two USE/EAP courses in the University of Ilorin, the low level of competence in English language skills demonstrated by students even after taking and passing the courses also attest to the ineffectiveness of the presentation of the programme to them. What this means is that the contextual variables have not exerted adequate positive pressure on the core aspect of our circle (p.8). The scenario painted calls for urgent positive attention so as to arrest the depreciating value of the products of the tertiary institutions. In this paper, attention is turned to the course books made available to the learner for USE. This is because an examination of the context of teaching USE reveals that the classes are extra large (at least 100 and above per USE class), the teachers are few; the hours of contact are too few for any meaningful impact to be made. When Tyler came up in 1949 with his theory of Systematic Curriculum Planning, little was known of the extent to which this theory would influence curriculum studies and, especially, language teaching. For instant, salient questions were raised to serve as built-in checks and balances technique for curriculum planning: (a) What educational purposes should the (teaching establishment) seek to attain? (b) What educational experiences can be provided that is likely to attain these purposes? (c) How can these educational experiences be effectively organized? (d) How can we determine whether these purposes are being attained? As far as applied linguistics is concerned, some of the following conclusions have been drawn from the questions above over the years: (i) Designs are based on organized body of knowledge. This involves academic discipline, specific contents, and systematic transfer of knowledge, i.e. intellectual development. 2 (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) Designs are based on specific competences. Here performance objectives are specified, and skills are learnt for particular purposes. Designs are based on social activities and problems: Here, language is seen as a tool for coping with daily social and economic demands. Designs are based on cognitive and learning processes: Language here ultimately becomes a means of strengthening learner’s ability to examine and solve problems on their own. Designs are based on feelings and attitude. Here, the end of planning has humanistic and affective ends. Learning becomes a means of bringing people together and the capacity to learn increases with the openness to others. Language then becomes the means of personality development. Designs are based on needs and interest(s) of learners. The focus here is the systematic assessment of learners’ language needs (Stevick, 1971 and Munby, 1978). The use of English (USE) programme in the higher institutions in Nigeria is expected to empower the learners with the communication skills for tertiary education. But the context of its presentation is considered to be ineffective (Babatunde, 2001). Babatunde (2002:8) submits that the socio-cultural, psychological, linguistic, educational, infrastructural and the administrative contexts of teaching USE are not positively utilized for the production of the desired outcome in the learners. A number of pertinent questions are then asked with respect to the health of this service programme: 1. What are USE teachers supposed to do with their learners in the classroom? 2. What are USE teachers able to do with their learners? 3. What do the learners do with USE classes? 4. To what extent are the learners able to benefit from what happens in the USE classes vis-à-vis the expected benefits of the programme? 5 What are the real sources of input for the learners in the USE programme and much are the learners able to make in take? 6. What can be done to achieve better results in the USE programme? The possible sources of input for learners in the USE classes are teachers, other students, and materials (largely in form of textbooks purchased by students at registration points). The classes are extra-large, so adopting an interactive, communicative approach is a near impossible task for the USE teacher. The lecture hours are inadequate and often appropriate venues are not found for lectures. Since the learners are supposed to have the course books and are expected to have some time to them to access its content, we can thus turn to materials for rescue. Doing a sample evaluative survey of some USE texts in the tertiary institutions should show us how much help learners can receive from the course books made available to them. This paper largely adapts Williams (1983) criteria for textbook evaluation and Cunningsworth (1984) checklist for course book evaluation to examine what learners stand to gain in the USE texts of the following institutions: (a) Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomosho (LAUTECH) 3 (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) (h) Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife. (OAU) Federal University of Technology, Akure. (FUTA) University of Ilorin, Ilorin. (UNILORIN) Federal Polytechnic, Bida. (FEPBIDA) University of Ibadan, Ibadan. (UI) Kwara State Polytechnic, Ilorin. (KWARAPOLY) University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos. (UNILAG) The evaluation was done with the aim of deciding whether or not the course books “can save learners” from the deficiencies imposed on the teaching of USE by the contextual variables; and to make sure, as far as possible, that the syllabus is properly covered and that exercises are effective and adequate. The evaluation was also carried out with the aim of finding out what the course books are making available to be learned, the overtly and covertly stated goals and the methodology promoted by the course books. We were also concerned with the humanistic values of education imparted through the course books. Now that our intention and methodology has been broadly set down, we shall now examine the literature of humanistic English language teaching and the promotion of learner autonomy through language programme. HUMANISTIC ENGLISH TEACHING Humanism is defined as “a system of beliefs concerned with the needs of people and not with their religious ideas.”(Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, 1995 edition: 700). Humanism which a “belief in human-based morality” is a system of thought that is based on the values, characteristics, and behavior that are believed to be best in human beings, rather than on any supernatural authority. It is also a concern with the needs, well-being, and interests of people (Microsoft® Encarta® 2006. © 1993-2005 Microsoft Corporation). The Renaisance humanists were concerned with the study of the ideas of the ancient Greeks and Romans. So it was outwardly directed; but in the 20th century, humanism is inward-looking as it uses the strategy of introspection to help people know themselves. Romantic humanism concentrates on feelings, experiences and ideas. Apart from the above, we also have Florentine, and even nowadays, Pragmatic humanism. Trying to define the precints of each of this is an unnecessary distraction. This paper is only concerned with bringing out the best in humanistic thinking to bear on the effective teaching of USE in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Arnold (1998:235) while dwelling on humanistic English teaching alludes to the fortune of ELT teachers with relish because all subjects are ours. Quoting Rivers (1976:96) she says, “whatever [the students] want to communicate about, whatever they want to read about is our subject matter.” Giroux and McLaren (1989: xiii) opine that language teachers are ‘transformative intellectuals who connect pedagogical theory and 4 practice to wider social issues… and embody in our teaching a vision of a better and more humane life.’ This is done without the imposition of the teacher’s values “because imposition of any kind is quite outside basic humanistic teaching philosophy” (Arnold, 1998: 238). Despite the fact that teaching is considered to be a political act, the teacher is cautioned to be very careful not to push a particular ‘philosophy’ or a particular morality on your students,but you will nevertheless be acting from your deepest convictions when you teach people to speak tactfully, to negotiate meaning harmoniously, to read critically, and to write persuasively. (Brown, 1994: 4412) In addition, Arnold (1998:238) quotes Kohonen and Kaikhonen’s (1996) summary of the Finland’s established goals of Education which recognize the importance of supporting a holistic personality development of the learner, democratic citizenship education, active learning through learner involvement, and ethical reflection and the respect of cultural diversity. The UNESCO (1996) report on education for the twenty-first century also concludes that education is the teaching ‘to understand, to do, to live together, to be”. Brown (1998:261) also submits that when incorporating critical thinking in the classroom we are helping our students “to become aware of information” and “to become participants in a global partnership of involvement in seeking solutions”. In short, The incorporation of elements of humanistic language teaching, with their emphasis on interpersonal communication, would, however, seem highly justifiable… (Arnold, 1998:240). Stevick (1980, 1990 and 1996) has given a lot of insight into humanistic language teaching. Emphasis is on two types of meaning in the literature – linguistic and personal. In other words, as the language items are presented, the learners also perceive “how the activity relates to (learner’s) immediate purposes, overall objectives, loyalties, selfimage, emotions and the like’. The requirements of humanistic language teaching are summed up as follows: a. A firm command of the language being taught; b. A proper training in language teaching methodology; c. A proper understanding of teacher’s emotional I.Q. d. A realistic understanding of learner’s language needs; e. An understanding of learner’s cognitive and affective requirements and personality, etc. The components of humanism examined with respect to the course books are feelings, social relations, responsibility, intellect, and self-actualization (Stevick, 1990:23-4). 5 LEARNER AUTONOMY IN THE LANGUAGE PROGRAMME Learner autonomy is often seen as a goal of all learning, especially in the Western culture. No wonder that Littlewood (1999: 73) observes: If we define autonomy in educational terms as involving students’capacity to use their learning independently of teachers, then autonomy would appear to be an incontrovertible goal for learners everywhere, since it is obvious that no students, anywhere, will have their teachers to accompany them throughout life. Autonomy as a philosophy is defined as “ existence as independent moral agent: personal independence and the capacity to make moral decisions and act on them.” (Microsoft® Encarta® 2006. © 1993-2005 Microsoft Corporation.) These definitions, among other things, reveal why autonomy as a goal is attractive in the language classroom where learners are expected to acquire skills they will use in and outside the classroom. The reasoning is that if learners have control over their own learning process, they will be able to develop expected language proficiency. One other crucial aspect of educational autonomy is the need to train learners to be autonomous. The learner who probably grew up to depend solely or largely on the teacher as the source of learning must be gradually sensitized to the need to take responsibility for aspects of the language learning process. Cotterall(2000) identifies five principles that are relevant in designing a course meant to foster learner autonomy. The principles are: learner goals, the language learning process, tasks, learner strategies, and reflection on learning(p. 1 00). The principles are said to contribute to the transfer of responsibility from teacher to learner. These principles are fairly common requirements for success in a learner-centered classroom. The submision on learner strategy however deserves some elaboration. Cotterall(2000:111 and114) explains that a course that is meant to make learners responsible for their learning incorporates discussion and practice with strategies that are capable of facilitating task performance. She argues further: At the heart of learner autonomy lies the concept of choice. This principle relates particularly to extending the choice of strategic behaviours available to learners, and to expanding their conceptual understanding of the contribution which strategies can make to their learning (111). At the core of strategic change is the shift of focus “from solving specific problems to providing experience of problem-solving”(110). There is the need to make learners understand the importance of strategic change and the learners’ choice of strategic behaviour must be extended in the programme. Focus on strategic change is a major support in the course for the tranfer of responsibility of decision-making from teacher to learner. The relevance of insight on strategic change is of immense relevance for the USE programme in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria because the ESL context makes training in pragmatic competence to be a neccesity. It is therefore important to examine the extent to which the USE texts show awareness of this principle. 6 An excellent way of promoting learner autonomy is the self-access system (Jones, 1995:228). Barnett and Jordan (1991: 310) submit that “the traditional view of self-access facilities is a place where individual users go to supplement classroom learning.” Jones also says: In setting up self-access facilities it is conveniently assumed that learner autonomy, whether full or partial, is a desirable objective. The ideal ‘good language learner’, after all, is said to be one who takes as much responsibility as possible for his or her own learning, and self-access is the most valid test of this responsibility(228). Undertaking a comprehensive review of the literature of autonomous learning and self-access language learning (SALL) is beyond the scope of this paper. We shall however outline a few issues in these concepts that will explicate their relevance for the evaluation of the USE texts in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria. The four types of SALL systems are: Menu-Driven, Supermarket, Controlledaccess, and Open-access. Among the rationale to be considered for setting up a SALL centre: Financial, Pedagogical, Ideological, and Prestigious (state of the art in learning). In addition, the key human resources are: Language Specialist, Computer Consultant, Librarian, Materials Developer, Administration/ Clerical Assistant and Technical/AV Specialist. SALL becomes a supplement for classroom learning where attention is paid to learner’s needs. SALL also has multi-media potentials and multi various applications (i.e. classroom, groups and individual). We shall now do an appraisal of the review done here as we focus on the essence of the concepts for the USE texts to be evaluated. HUMANISM, AUTONOMOUS LEARNING AND USE TEXTS The flexibilities and compromises in conceptualizing autonomy reveal, among other things that autonomy is not an all-or-nothing concept (Holec, 1981:2; Oxford, 1990:10) Autonomy may come by degrees and learners may have differential level of autonomy with respect to language skills. The relevant self-access system is the controlled access. This enables the teacher to “direct” learners to learn specific aspects of language on their own. The overriding consideration is pedagogical, nothing ornamental about it. The key resources in our own case are the materials, the material developer and the teacher. The strategies to be used have to do with the classroom, the group and the individual. There are at least five overlapping components of humanism relevant here: feelings, social relations, responsibility, intellect and self-actualization. The review of literature on evaluation (especially evaluation criteria, humanism and autonomous learning suggest the following relevant factors and approaches for an effective USE text in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria: 1. Interactive presentation of tasks; 2. Positive attitude (motivation, etc.) 3. Language skills acquisition as a systematic process; 7 4. Learning awareness strategies (meta-cognitive: goals – setting, selfassessment, etc.); 5. Text exploration devices – encouragement given to learners to ensure and enhance learning, retention and use: exercises, tasks, worksheets, etc. 6. Memory jogging devices- facilitation of review and revision, self monitoring ends; 7. Language use/language competence demonstration opportunities – endproduct is communication; 8. Ascertain link and relevance with (specific) learner’s discipline; and 9. Devolving of power from teacher to students – students as ultimate determinant of success. For the ease of analysis, the foregoing issues have been reduced to a set of tangible issues referred to here as criteria for USE/EAP textbook evaluation. This is presented below: CRITERIA FOR USE/EAP TEXTBOOK EVALUATION 1. General (15 Marks) - Takes into account currently accepted methods of ESL/EFL teaching - Gives guidance in the presentation of language items - Caters for individual difference in home language background. - Relates content to the learners’ and environment. - Incorporates autonomous learning features 2. Speech (10 Marks) - Is on a contrastive analysis of English and L1 sound system - Suggests ways of demonstrating and practicing speech items - Includes speech situations relevant to the learners’ background - Allows for variation in the accents of non-native speakers 3. Grammar (10 Marks) - Stresses communicative competence in teaching structural items - Provides adequate models featuring the structures to be taught - Shows clearly the kinds of responses required in drills (e.g substitution) - Selects structures with regard to differences between L1 and L2 cultures 4. Vocabulary (10 Marks) - Selects vocabulary on the basis of frequency, functional load, etc. - Distinguishes between receptive and productive skills in vocabulary teaching. - Presents vocabulary in appropriate contexts and situations. 8 - Focuses on problems of usage related to social background. 5. Reading (20 Marks) - Offers exercises for understanding of plain sense and implied meaning - Relates reading passages to the learners’ academic background - Selects passages within the learners’ professional/academic registers - Selects passages reflecting a variety of styles of contemporary English - Gives adequate exposure to and practice in note-making, outlining and summarization skills 6. Writing (20 Marks) - Relates written work to structures and vocabulary practiced orally - Gives practices in controlled and guided essay writing - Relates written work to the learners’ age, interests, environment and profession - Demonstrates techniques for handling aspects of composition teaching - Presents writing as interaction and as a process - Leads learners to acquire self-editing skills 7. Technical (15 Marks) - Is up-to-date in the technical aspects of textbook production and design - Shows quality in editing and publishing (cover, typeface, illustration, etc). - Is durable and not too expensive. - Has authenticity in language and style of writing. The scores given to the sections indicate the relative grade of the aspects as determined by their relative importance in the USE/EAP programme in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria. What follows is the tabular presentation of the analysis of the texts selected for this study. 9 DATA PRESENTATION Criteria 1(15) 2(10) 3(10) 4(10) 5(20) 6(20) 7(15) 7 4 6 7 9 11 8 Total 100 52 B 8 5 7 7 12 11 10 60 C 6 4 5 6 9 12 8 40 11 7 7 6 13 13 12 70 8 7 6 6 11 11 11 60 F 8 7 7 7 14 14 12 69 KWARA 7 5 6 6 11 11 11 57 10 7 7 7 12 14 12 69 LAUTECH A OAU FUTA UNILORIN D FEP BIDA E UI POLY G UNILAG H FIGURE 1: TABLE SHOWING THE ANALYSIS OF EIGHT ‘USE’ TEXTS FINDINGS Most of the evaluated course books fall short of the requirements of being able to train the learners to have adequate proficiency in the use of the English language for higher education and use after their training in their professions. Not strictly in the aspect of (language) content, but largely in terms of the learning strategies (i.e. learner training), learning processes, learning activities and tasks, activity management and guidance. The low scores are due to presentation of course books that do not recognize the need to facilitate autonomous learning. Four of the texts, The Use of English: A Text (OAU), Effective Communication in Higher Education: The Use of English (Unilorin), English Language Communication Skills For Academic Purpose (U.I) and Communicative English and Study Skills (Unilag) have fairly high ratings in terms of the requirements. A major problem with the OAU text is its age, published in 1975! Though the language content is appropriate, the examples, tasks and passages are largely outdated. Much of these are mere historical documents which are out of tune with the realities of the 21st century. The Unilorin text is not heavy enough in terms of adequate tasks that can train learners in the language skills discussed. These exercises are too few in most cases to engage the attention of learners adequately for skills’ acquisition. All the texts do not have adequate guidance for learners with respect to self-monitoring and error correction. 10 For instance, none of the texts provide answers to the exercises and tasks given. This lack detracts considerably from the qualities of the course books for learner-training. If any communication skills programme is to be effective, it must have three main timetabled elements: Class Time, Self-Access Time and Private Consultation Time (Allwright, 1981:12). In the context of USE in Nigeria, class time and private consultation time are not reliable due to extra-large classes. In addition, there are no organized self-access facilities; as such, course books can and should be effectively used to ensure some degree of the achievement of programme goals and objectives. CONCLUSION In this study we have designed a USE course book evaluation criteria which utilizes insights from humanistic philosophy and autonomous learning principles to assess the worth of the textbooks used in eight tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Most of the materials are found wanting in terms of the potentials to assist the learners in attaining the required level of competence in the English language; that is in the context of other aspects of programme implementation inadequacies. The USE programmes should aim at a proficiency level for learners such that the cognitive, affective and psychomotor aspects of the learner’s personality are affected. The course books should not be made with the aim of just raising funds for the institutions and the authors, rather, they can be packaged to contribute in no small measure to the holistic language and personality development of the learners for personal and national development. The study therefore recommends that the evaluation criteria presented can be a useful guide in the development of USE materials in the tertiary institutions in Nigeria. The evaluation framework will ensure a high degree of the achievement of programme goals and ensure that the course books are really mindful of the interest of learners. 11 BIBLOGRAPHY A. REVIEWED TEXTS Adegbija, E.E. (ed.) (1998) Effective Communication in Higher Institution: The Use of English. Ilorin: Unilorin Press. Adetugbo, A (1997) Communicative English and Study Skills. Lagos: University of Lagos Press. Alo, Moses and Ogunsiji, Ayo (eds.) (2004) English Language Communication Skills Academic Purposes. Ibadan: General Studies Programme Unit, University of Ibadan. Department of English, University of Ife, Ile-Ife (1975) The Use of English: A Text. Ibadan: Caxton Press Limited. Department of General Studies, LAUTECH (No date), Use of English. Ogbomosho Tonga, A. N. (ed.) Use of English for Polytechnics. Vol. 1. Bida: Jube-Evans Books And Publications. __________ (ed.) Use of English for Polytechnics. Vol. 2. Lagos: Stirling-Horden Publishers (Nigeria) Ltd. B. REFERENCES Allwright, R. (1981) “What do we want teaching materials for?” ELT Journal 36/1:5-18. Arnold, Jane (1998) “Towards more humanistic English teaching.” ELT Journal 52/3: 235-242 Babatunde, S.T, (2001) “The Context of Teaching the Use of English Courses in Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria: The Unilorin Example”. CENTERPOINT: Vol. 10, No 1 (pp. 1-9) Barnett, L. and Jordan, G. (1991) “Self-Access Facilities: what are they for?” ELT Journal 45/4:305-312 Brown, (1998) “Language program evaluation: a synthesis of existing possibilities” in R.K. Johnson (ed.) The Second Language Curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (pp222-240) Cotterall, Sara (2000) “Promoting learner autonomy through the curriculum: principles of designing language courses”. ELT Journal. 54/2: 109-117 Cunningsworth , A (1979) “Evaluating course materials” in S. Holden (ed.) : Teacher Training, London: Modern Publications. Giroux, H. and P. McLaren (1989) Critical Pedagogy, the State, and Cultural Struggle. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Holec, H. (1981) Autonomy and Foreign Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon Jones, (1995) Kohonen, V. and P. Kaikkonen (1996) “Exploring new ways of in service teacher Education teacher education: an action research project” Paper presented at the European Educational Research Association Conference, Seville, Spain. Littlewood, W. (1999) “Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts”. Applied Linguistics, 20/1: 71-94. 12 Munby, J. (1978) Communicative Syllabus Design, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary (1990) Stevick, E.W.(1971) Adapting and Writing Language Lessons. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State. UNESCO (1996) Williams, D. (1983) “Developing criteria for textbook evaluation” 37/3: 251-255 13