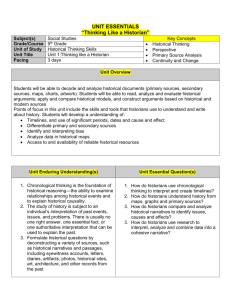

Herodotus & Thucydides: Historical Reasoning

advertisement