Compare how the supply and the scarcity of natural resources

advertisement

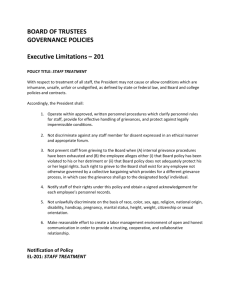

Compare how the supply and the scarcity of natural resources influences the conduct of contemporary conflict. Robin Solomon (rs342), IR5001, November 2005 Word count: Summary This essay examines the role that the natural resource of oil, both its abundance and scarcity, has on contemporary conflict. Conflict for the purposes of the discussion is broadly defined to include violent and non-violent interactions, involving states and non-state organizations. The major theories informing the study of natural resources and conflict are reviewed and their findings with respect to oil are cross-examined. An overview is provided of the unique characteristics that shape oil related conflicts. Finally, the current geopolitical environment surrounding oil dependence is analyzed; with an emphasis on non-violent conflicts emerging from competition for scarce oil resources that could in the next decade become violent. Contemporary conflict and security within the natural resource context The bi-polar balance of power between the U.S. and the Soviet Union has yielded to a multi-polar environment where asymmetrical conflicts are more likely to arise. The black and white picture of conflict in the Cold War, in which enemies were clearly defined, is now largely grey and arguably has left “the overall state of current conflict typology in a state of confusion”1 and has ushered in a “new world disorder.”2 Conflicts are still driven by differences in ideology but are increasingly characterized by a more complex set of underlying causes including but not limited to: ethnicity, culture, religion, and nationalist/separatist ideology. 3 War is typically defined as military engagement conducted between states involving greater than 1,000 casualties.4 Conflict, however, can be inter or intrastate, high or low intensity5 and may or may not involve the military. Conflict can be violent but can also be based solely on discordant dialogue. As articulated in the book, Contemporary Conflict Resolution, there is not a simple definition.6 While conflicts involving oil may have originated long before the break-up of the Soviet Union, the conflict dynamics examined in this essay are largely related to the post-Cold War period. The author considers that conflict can be intra and/or interstate, involve nonstate players, can be violent and/or have the potential to become violent. However, conflict also can be non-violent and be predominately viewed as geopolitical posturing through a state’s projection of military force capabilities, formation of 1 Miall, Hugh, Oliver Ramsbotham and Tom Woodhouse, Contemporary Conflict Resolution: The prevention, management and transformation of deadly conflicts, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000), p. 29. 2 Hampson, Fen Osler, and David Malone, From Reaction to Conflict Prevention, (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002), p. 28. 3 Rupesinghe, Kumar (ed.), Conflict Transformation, (Houndsmills: Palgrave, 1995), p. 66. 4 Sambanis, Nicholas, “What is Civil War? Conceptual and Empirical Complexities of an Operational Definition”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Volume 48, No. 6 (December 2004), p. 815. 5 Miall, Ramsbotham and Woodhouse, ?, p. 27. 6 Miall, Ramsbotham and Woodhouse, ?, p. 66. geostrategic alliances and rhetoric. Throughout this essay, the term supply is used interchangeably with abundance and scarcity is often referred to in terms of resource dependence. The break-up of the Soviet Union has led to constantly changing political, economic and social environments where globalization and economic development play an increasingly important role in shaping conflict dynamics, including onset, duration and resolution. The landscape of contemporary conflict is distinguished by some of the following elements (illustrative): Access to information and communication technologies; Globalization of economies (i.e. increased interdependence and ease of transnational shipments of commodities); Availability of sophisticated military technology and hardware; Sophistication of international financial networks; In the past, states primarily had access to military and civilian technologies. In contemporary conflicts, however, especially civil wars in oil rich countries, both rebel groups and governments can access sophisticated financial, military, information and transportation networks. Two fields of security studies, environmental and economic, have become associated with natural resources and conflict. The security lexicon and the environmental lexicons are very different and as Lorraine Elliott notes in The Global Politics of the Environment, one “can’t just militarize environmental politics or demilitarize security thinking.”7 While both elements of security studies are vital to addressing post-Cold war natural resource conflicts, 8/9 the economic security field has developed a more dynamic body of research on oil. This body of research has examined how the need for secure supplies of oil shape security strategies and elements of conflict of oil dependent states, and has undertaken in-depth research on conflict in states that have an abundance of oil. The U.S. ‘securitization’ of oil began in 1980, after the oil crises of the 1970’s and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. U.S. President Jimmy Carter decided oil was a strategic resource vital to U.S. security. In what has become referred to as ‘The Carter Doctrine,’ he asserted “Any attempt by an outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America…[and] will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”10 President Carter laid the foundations for the development of a significant U.S. military infrastructure in the Persian Gulf to address potential and actual conflict in the region. 11 By linking the supply of oil to national security, the dynamics of conflict around oil changed. The Carter Doctrine made it possible for the U.S. to go 7 Elliott, Lorraine, The Global Politics of the Environment, (Houndmills: MacMillan Press, 1998), p. 220, 221 & 240. 8 Matthew, Richard, “In Defense of Environment and Security Research”, U.S. National Intelligence Council, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, August 2002, p. 1. 9 Elliott, The Global Politics of the Environment, p. 238. 10 Klare, Michael, Resource Wars: The new landscape of global conflict, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002), p. 4. 11 Klare, Resource Wars, p. 61. beyond traditional diplomacy by justifying pre-emptive strikes and implementation of defensive military measures. The conflict landscape linked to oil dependence by industrialized states is extremely complicated. Primarily non-violent conflict dynamics are constantly evolving amongst powerful nations as they vie for control over scarce oil resources critical to their economic survival. The recognition of the need to secure energy supplies from areas characterized by conflict is evident in the U.S. National Energy Policy (NEP), published in May 2001. The NEP acknowledges that the Persian Gulf will “remain vital to U.S. interests” and emphasizes the importance of the “Western Hemisphere, Africa and the Caspian” to help meet increased U.S. oil demand.12 The U.S. is not alone in acknowledging the link between oil dependence and security. The European Union, United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have embraced environmental security, including natural resources, as a strategic concept.13/14 Major Theories on the Role of Supply and Scarcity in Natural Resource Conflicts There is a substantial body of evidence “that resources and civil wars are causally linked.”15 Different scholarly schools of thought have different ways of examining the causal relationship between natural resources and conflict. In order to understand the relationship of oil and conflict, it is critical to examine the primary theories informing the debate on the causal links; typically referred to as ‘greed versus grievance’ and a further school of thought ‘beyond greed and grievance’. Grievance Academics and policy specialists from one school of thought argue resource scarcity drives conflict through grievance; resource scarcity can cause citizens to grow disillusioned with state leaders, this disillusionment can turn into grievance which in turn can lead to violent conflict. Thomas Homer-Dixon, the “Toronto School,” and Robert Kaplan16 are recognized leaders in the field of grievance studies. While often a source of conflict, resource scarcity argues Homer-Dixon can sometimes be turned into a benefit for the state by promoting: innovation (alternative energy), government accountability (taxation required instead of money from sales of resources), and investment in human capital. (SOURCE) According to the grievance school of thought, “scarcities of renewable resources do produce conflict and instability. However…the mechanisms by which this happens are complex and environmental scarcity essentially produces conflict by generating social effects, such as poverty and migrations.” There are limitations with Homer-Dixon and the grievance school’s approach, however, when examining the dynamics of oil and conflict. Grievance studies have National Energy Policy, “Report of the National Energy Policy Development Group”, Washington, May 2001, Chapter 8, p. 3 & 4. 13 Elliott, ?, p. 230. 14 “Environmental Security: United Nations Doctrine for Managing Environmental Issues in Military Actions”, AC/UNU Millennium Project, 2003 (http://www.acunu.org/millennium/es-un-execsum.html - accessed on November 20, 2005). 15 Ballentine, Karen and Jake Sherman, (eds.), The political economy of armed conflict: beyond greed and grievance, (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003), p. 48. 16 Nevins, Joseph, “Resource Conflicts in a New World Order”, Geopolitics, Volume 9, No. 1, (Spring 2004), p. 258. 12 largely been based on the assumption that non-renewable natural resources are in oversupply and therefore do not influence conflict.17 They have focused primarily on developing countries in the southern hemisphere, where conflicts tend to be intrastate and violent, and thus there is limited grievance research on interstate wars such as the Iraq-Kuwait War (1991) and the Iraq War (2003). By focusing on scarcity in developing countries, this school pays less attention to resource dependence in the industrialized world, and its potential to influence conflict, especially non-violent. Finally, the notion that there is an oversupply of oil is inaccurate (see pages 14-16). Greed The field of political ecology18 has emerged to examine the role of natural resource abundance rather than scarcity in conflict. Political ecologists generally argue abundance (greed), not scarcity (grievance), is the main cause of natural resource conflict. Conflict theory related to natural resource abundance is also referred to as the ‘paradox of plenty’ or the ‘resource curse’.19 Paul Collier and from the World Bank, and Philippe Le Billon from Oxford University, are widely credited with developing what has come to be termed the study of ‘political ecology’. The research undertaken by political ecologists indicates resource rich countries are 20% more likely to go to war than countries that have a scarcity of resources.20/21 In the case of resource abundance, governments obtain ‘rents’22 from natural resources such as oil and the negative consequences on governance and societies can be tremendous. “Through a ‘renter’ effect, governments can rely on fiscal transfers from resource rents, rather than statecraft, to sustain their regime. Rents from oil are considered “differentially important in conflict risk.”23 The income generated from oil exports can create an enmeshed network between governments, private companies and in some cases even guerrilla organizations as well as promotes a system of patronage and even in some cases prolong conflict. 24/25 Philipe Le Billon in his Adelphi Paper, “Fuelling War: Natural Resources and Armed Conflict”, assesses conflicts in accordance with a matrix based on resource characteristics. Le Billon asserts “the specific characteristics of a resource, its location and its mode of exploitation can affect the balance of power between belligerents.”26 He examines the prevalence of different types of conflict (i.e. state control/coup d’etat, secession, peasant/mass rebellion and warlordism) through the prism of two sets of resource characteristics: geography - whether the resource is proximate (i.e. easier for governments to control) or distant (i.e. remote locations near 17 Nevins, Joseph, full text. Peters, p. 190 & 191. 19 Le Billon, Philipe and Fouad El Khatib, “From Free Oil to ‘Freedom Oil’: Terrorism, War and U.S. Geopolitics in the Persian Gulf”, Geopolitics, Volume 9, No. 1 (Spring 2004), p. 111. 20 IR5007 lecture on natural resources, Dr. Taylor, November ?, 2005. 21 Auty, Richard, “Natural Resources and Civil Strife: A Two-Stage Process”, Geopolitics, (January 20, 2004), p. 29. 22 Collier and Hoeffler, Resource Rents, p. 7. 23 Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler, Resource rents, p. 7. 24 “Resources can induce patronage politics”, Collier and Hoeffler, Resource Rents, p. 14. 25 “There is a new reason for policy concern over the risk from primary commodities [oil]: they generate the worst sort of civil wars”, Collier and Hoeffler, Resource Rents, p. 4 26 Le Billon, Philippe, Fuelling War: Natural resources and armed conflict, Adelphi Paper 373, (Abingdon: Routledge, March 2005), p 31. 18 porous borders); and exploitation characteristics - diffuse (i.e. across broad swaths of land such as crops, timber or gems) or point (i.e. located in single locations such as oil and gas). Le Billon characterizes oil as a point resource that can be both proximate and distant. His study of specific oil conflicts leads him to conclude they typically involve governments. Examples of violence related to state control of oil include: Congo-Brazzaville, Colombia, Iraq-Kuwait, and Yemen. Conflicts resulting from secessionist movements include: Angola, Chechnya, Nigeria and Sudan. One of the best known and most widely quoted statistical models created to study the role of natural resources in conflict was developed in 2003 by Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler for The World Bank. Their economic model of civil war based on quantitative empirical analysis considers a range of issues: initiation, duration, repetition, costs, and post-conflict recovery. 27 Of the multiple factors examined, three had the most statistical relevance: level of income per capita, rate of economic growth and structure of the economy, namely dependence on primary commodity exports.28 Specifically regarding vulnerability to conflict, Collier and Hoeffler reached the conclusion that resource abundance creates four conditions, which can sow the seeds for civil strife. These include economic growth collapse, low educational attainment, a large cohort of unemployed young males and high resource dependence.29 Collier, Hoeffler and another member of their team, Ian Bannon, undertook statistical research specifically examining the effect of oil on conflict.30 In developing countries where natural resource revenues account for more than 50% of gross domestic product (GDP), they determined the risk of secessionist war increases by approximately 38%. If a country has oil the risk increases to 100%. (SOURCE/PAGE) Collier’s (et-al) research has led him to conclude, “if oil is present a rebellion it is almost certain to be secessionist.”31 The oil related conflicts noted by Collier (et-al) include: Aceh (Indonesia), Biafra (Nigeria), Cabinda (Angola), Katanga (ex-Congo) and West Papua (Indonesia). In these cases, greed and grievance are interconnected; state leaders are motivated to maintain control of oil and generally have not distributed wealth amongst their constituents. The lack of wealth sharing has given rise to grievance and rebel secessionist groups have emerged. The rebel groups, however, also become trapped in the greed cycle of conflict. Through extortion of companies exploiting oil and theft from illegally tapping into pipelines, the rebel groups often receive important financing for their guerrilla campaigns.32 In this case both greed and grievance are literally fuelling conflict. The main weakness with Collier’s (et-al) research is that it focuses exclusively on violent intrastate wars and does not capture interstate or non-violent conflict dynamics in its economic modelling. 27 Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler, 2003 in World Bank Natural Resources and Violent Conflict, p. 2. Bannon, Ian and Paul Collier, (eds.), “Natural Resources and Violent Conflict: Options and Actions”, The World Bank, 2003, p. 2. 29 Auty, Richard, “Natural Resources and Civil Strife: A Two-Stage Process”, Geopolitics, (January 20, 2004), p. 46. 30 Bannon, Ian and Paul Collier, (eds.), “Natural Resources and Violent Conflict: Options and Actions”, The World Bank, 2003. 31 Collier and Hoeffler, Resource Rents, p. 10. 32 Collier, Bannon, p. 5. (MORE?) 28 Beyond Greed and Grievance A third school of study has emerged to examine the relationship between natural resources and conflict and the body of research is generally published under the rubric ‘beyond greed and grievance’.33 Karen Ballentine and Jake Sherman have undertaken some of the most in-depth statistical analysis in this area. They argue there is a “Need to weigh economic factors vis-à-vis the role played by other political, cultural, and strategic factors in shaping the incidence, duration, and character of intrastate conflict.”34 Ballentine and Sherman developed seven hypotheses on resources and conflict – two of which are directly related to oil: “the more unlootable a resource is [i.e. Le Billon – point] the more likely it will lead to separatist conflicts; the more a resource is obstructable [i.e. Le Billon – distant] the more likely there is for an increase in the duration and intensity of conflicts.”35 They study eight separatist conflicts, of which five have unlootable resources and two involve oil: Angola (Cabinda) and Sudan. They identified two oil related conflicts in which obstructability played a key role: Sudan and Columbia. They also researched financial flows and found that out of the eight cases, “revenues went exclusively to the government in four cases and to both sides [rebels/government] in four cases.” 36 In both Columbia and Sudan, the obstructable nature of their land-locked oil resources influenced conflict because both sides received revenues.37 Regarding oil, one can draw the conclusion from Ballentine and Sherman’s research that where oil is abundant there is a higher likelihood of secessionist conflict. If obstructable (i.e. primarily in the ground in remote locations), oil has a high potential to be a source of both grievance and greed for secessionist groups. Michael Klare is a well-known author on the subject of natural resources and conflict. His research and writing could arguably be classified as belonging to the ‘beyond greed and grievance’ school of thought. Klare’s work emphasizes the role of natural resource dependence, beyond the rigid understanding of scarcity, in shaping contemporary conflict, both inter and intrastate. Klare also studies grievance motivated conflicts, especially involving ‘lootable’38 natural resources such as diamonds and timber. In his book Resource Wars, Klare outlines three factors he believes distinguish contemporary resource conflicts: “relentless expansion in worldwide demand, the emergence of significant resource shortages and the proliferation of ownership contests.”39 Just as there is a paradox within the greed paradigm, whereby not just governments but secessionist leaders can become dependent on financing from oil, many of the oil conflict examples used by Klare point out the paradox of oil dependence; on the one hand it makes a nation’s economy strong, but on the other it leaves the nation vulnerable. Klare argues this dichotomy between strength and vulnerability greatly influences conflict around oil and will 33 Le Billon, Philippe, Fuelling War: Natural Resources and Armed Conflict, Adelphi Paper 373, (Abingdon: Routledge, March 2005), p. 8. 34 Ballentine, Karen and Jake Sherman, (eds.), The Political Economy of Armed Conflict: Beyond Greed and Grievance, (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003), p. 5. 35 Ballentine and Sherman, p. 54-55. 36 Ballentine and Sherman, p. 57. 37 Ballentine and Sherman, p. 57. 38 Klare, Michael, Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002), p. 23.p. 13. 39 Klare, Resource Wars, p. 23. cause there to be more conflicts driven by dependence and scarcity in the future, rather than greed.40 While Homer-Dixon, Le Billon, Collier and Klare may not agree on many issues, there is one common characteristic of oil and conflict they do agree upon: the fact that the availability of oil does not in and of itself cause conflict but rather is part of a more complex set of variables that can predispose a state or region to conflict.41 While there may be as wide a variety of opinions on the links between natural resources and conflict, most international relations specialists agree, “conflict over resources will remain a conspicuous feature of the international security environment.”42 Specific Examples of Oil Abundance Conflicts In cross-referencing the research by Le Billon, Collier (et-al), Ballentine/Sherman and Klare, some common conflicts related to oil abundance emerge:43 Where oil resources are point or unlootable (i.e. offshore or close to urban centres) conflict is likely to take the form of challenge to state control through a coup d’etat: Algeria, Angola, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Iraq-Iran, and IraqKuwait; Where oil resources are distant or obstructable (i.e. inland and require transportation to ports via a pipeline network) conflict is likely to be secessionist in nature: Angola (Cabinda), Caucasus, Nigeria (Biafra), Sudan, and Columbia. In addition to the above variables, the type of oil produced by a country can play a role in greed motivated conflict through the potential to obtain higher resource rents. Light, sweet crude oil of low sulphur content is the most valuable type of petroleum because it is most easily refined. Countries such as Nigeria and Angola have sweeter, lighter crude which might make them more prone to conflict that countries such as Venezuela or Saudi Arabia that tend to have heavier, sour oil. 44 In Nigeria, in particular, the high resource rents from its high quality oil have been considered an element in prolonging the violent conflict between rebel and government forces. Nigeria produces approximately 2.3 million barrels of oil per day and the violent secessionist conflict that developed in the River States of the Niger Delta, where a large part of the country’s oil resources are located, is extremely complex.45 The secessionist civil war in Nigeria has its origins in the grievances of the local population but the secessionist groups were able to obtain financing through a variety of illegal means, including extortion, kidnapping and sabotage and/or seizure of oil facilities; 46 “Secessionist movements or efforts to oust a government start with 40 Klare, Blood and Oil, p. 11. (FIRST?) Bannon, Ian and Paul Collier, (eds.), “Natural Resources and Violent Conflict: Options and Actions”, The World Bank, 2003, p. ix. 42 Klare, Blood and Oil, p. xiii. 43 Le Billon, Political Ecology of War, p. 573. 44 British Petroleum Statistical Review of World Energy 2005 (www.bp.com/statisticalreview), p. 12. 45 OPEC Production - Table 3a, EIA, November 2005. (MORE?) 46 “World Energy Hotspots”, September 2005, p. 7. (http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/World_Energy_Hotspots/Overview.html - accessed on October 31, 2005). 41 certain ideals but turn into opportunistic endeavours to gain wealth and power.”47 Since much of the Niger Delta’s oil passes through pipeline systems (obstructable) it’s an easy target for sabotage; between January 2004 and September 2004, there were 581 cases of pipeline vandalism reported.48 The profit’s from large-scale sealing from oil pipelines in the Delta region are reported to be approximately $1 billion per year, with sales primarily to East Asia.49 The Nigerian state’s response has been characterized by the use of force.50 The greed and grievance paradigm in Nigeria has all the hallmarks of conflict in a developing country as outlined on page 7. Sudan produces 301,000 million barrels a day of oil and oil accounts for more than 80% of the Nigerian Federal Government’s revenue.51 Oil abundance in Sudan provides an excellent example of how greed and grievance shape conflict where civil war was waged for 19 years and has cost 2 million lives.52 The separatist organization, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), is based in southern Sudan (upper Nile region) where there are significant oil reserves. Initially, the SPLA used guerrilla tactics to forward their cause. They targeted oil companies operating in the region through extortion, kidnapping and infrastructure sabotage and the money financed their operations. While the conflict has been on and off again over the 19 year period, the Sudanese government led a renewed military campaign against the rebels in 1999 in order to gain control of the oil fields in the south. “The government used summary executions, rape, ground attacks, helicopter gunships, and high-altitude bombings to force tens of thousands of people from their homes in the oil region.”53 The Sudanese government became heavily reliant on resource rents and was largely motivated by greed to increase these rents thus moving to use military force to re-gain control of the south.54 While a cease-fire agreement was reached in January 2005, there are still thousands of Sudanese refugees living in Ethiopia and the relationship between government and rebel forces has been termed “a cold peace.”55 As the above examples demonstrate, greed and grievance can shape conflict in two very distinct ways. An abundance of natural resources can lead to the emergence of separatist conflicts motivated by grievance. Secessionists claim ownership of the resources based on ethnic or tribal rights but also claim that national authorities misuse the resource rents. While secessionist groups can emerge with legitimate aspirations to create an independent state where resource wealth is equally shared, what often happens is rebels find a way to benefit from the resource wealth themselves and their motivations transform from grievance to greed; profit taking replaces separatist ideology. This dynamic can especially be seen in conflicts where Weinstein, Jeremy, “Resources and the Information Problem in Rebel Recruitment”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Volume 49, No. 4 (2005). 48 World Energy Hotpots, U.S. Energy Information Administration, p. 7. (MORE?) 49 Collier and Hoeffler, Resource Rents, p. 14. 50 Florquin, Nicolas, and Eric G. Berman, “Armed and Aimless: Armed Groups, Guns and Human Security in the ECOWAS Region”, A Small Arms Survey Publication, April 26, 2004, p. 27. 51 Booker, Salih and William Minter, “The U.S. and Nigeria: thinking beyond oil”, USA-Africa Institute, Volume 1, Issue 4 (Winter 2003), p. 27. 52 “Dialogue or Destruction? Organising for Peace as the War in Sudan Escalates”, International Crisis Group, Africa Report Number 48 (June 27, 2002), p. 1. 53 Ballentine and Sherman, p. 62-63. 54 “Africa Policy Outlook 2001”, Africa Policy Information Center, January 2001. 55 “South Sudanese bemoan lack of peace”, Reuters, November 21, 2005, (www.today.reuters.com/news - accessed on November 22, 2005). 47 oil is located in the interior of a country. Resource abundance can also lead governments to engage in violent conflict to gain or maintain control over resource rents. Dictatorial and authoritarian regimes that are plagued by corruption often become reliant on the benefits that come with lucrative oil revenues and “spoil politics takes over.”56 Characteristics of Oil Scarcity and Dependence in Contemporary Conflict Within the study of political ecology, few researchers have focused on oil scarcity and its links to conflict, with Michael Klare a notable exception. While oil “fuels military power, national treasuries, and international politics”57 it happens to be located predominately in regions and states vulnerable to conflict. There is currently more evidence pointing to resource abundance driving conflict, but over the long term there are signs that dependence and increasing resource scarcity could become more prevalent in conflicts. Three elements distinguish contemporary conflict linked to the scarcity of and dependence on oil: oil’s physical characteristics; violent inter-state conflicts involving military intervention; large number of non-violent geo-strategic manoeuvring between states aiming to gain exclusive access to long-term oil supplies, which have the potential to lead to violent conflict. Characteristics of Oil – Conflict Vulnerability Le Billon, Collier and Ballentine/Sherman characterize oil as a non-renewable, point resource that is often obstructable. While these characteristics make the resource vulnerable in countries where oil is abundant, they also influence the scarcity side of the equation where there is constant tension between supply and demand. With global economic expansion comes increasing oil consumption. “While there is much debate with regard to supply, there does not seem to be any disagreement that demand will increase significantly in the coming decades.”58 Oil consumption during 2004 increased to 80.75 million barrels per day (MBD), which represented a 3.4% increase from 2003 and was the largest increase in terms of volume since 1976.59 Global oil production in 2004 was 80.26 MBD. (?SOURCE) While production has largely kept up with demand, there is a lack of excess production capacity, which plays into the scarcity equation. Out of the OPEC’s 11 producing nations, only three are not producing at capacity.60 In addition to basic supply/demand dynamics, there are other oil industry factors influencing scarcity concerns: The means to transport oil (pipelines/maritime routes) are vulnerable targets for nationalist/separatist groups or terrorist organizations. Over 40 million barrels of oil per day are moved by tanker,61 and over 85% of oil from the 56 Le Billon, The political ecology of war, p. 568. Klare, Michael, Blood and Oil, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004), p. 9. 58 Peters, Susanne, “Coercive Western Energy Security Strategies: ‘Resource Wars’ as a New Threat to Global Security”, Geopolitics, Volume 91 (January 20, 2004), p. 192. 59 BP Statistical Review 2005, p. 2 and 9. 60 U.S. Energy Information Agency, Table 3a. OPEC Oil Production, October 2005 (www.eia.gov/emmeu/steo/pub/3atab.html - accessed on November 3, 2005). 61 Country Analysis Brief, “World Oil Transit Chokepoints”, Energy Information Administration, November 2005. 57 Persian Gulf transits the Straits of Hormuz.62 There are a further eight ‘chokepoints’ around the world that are considered vulnerable to conflict.63 Pipeline capacity is also an issue with most major pipelines operating at full or near full capacity. As demonstrated in the case of Nigeria, pipelines are extremely vulnerable targets in conflict. Russia’s Friendship Pipeline accounts for approximately 42% of Russian oil and gas exports to the European market64; “The vulnerabilities of Russia’s energy-export corridors are a source of significant concern,”65 especially to the EU. 66 Vital Russian pipelines cross conflict ridden regions in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) including Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan where nationalist groups operate. Russia’s ongoing conflict with Chechen separatists is also cause for concern. Furthermore, new pipeline routes tend to be in conflict zones. For instance the construction of a proposed pipeline route between Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan has been delayed for many years due to conflict.67 Shortages of oil tankers, drilling rigs and refining capacity all impact supply. Between 2003 and 2004, global refining capacity decreased in spite of increased petroleum product output.68 Over the long-term, scarcity fears are driven by a perception that depletion of proven reserves is taking place more rapidly than new reserves are being discovered, explored and brought on-line and thus demand will eventually exceed supply. Exactly when the balance will shift is the subject of heated debate amongst global oil experts. The British Petroleum 2005 Statistical Review for Energy indicates a less than 40-year supply of fossil fuel at current rates of consumption and current levels of new reserves coming on-line.69 In his recently published book, Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy, oil industry expert Matthew Simmons has brought the issue of ‘peak oil’ into the spotlight. ‘Peak oil’ refers to the debate about whether global oil output has already reached its maximum potential.70 Simmons and other energy industry experts who share the ‘peak oil’ view, do not believe efficiency measures or improved technology will substantially impact 62 Le Billon and El Khatib, p. 115. Country Analysis Brief, “World Oil Transit Chokepoints”, Energy Information Administration, November 2005. 64 BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2005 (PAGE?). 65 Le Billon and El Khatib, p. 124. 66 Peters, Susanne, “Coercive Western Energy Security Strategies: ‘Resource Wars’ as a New Threat to Global Security”, Geopolitics, Volume 91 (January 20, 2004), p. 206. 67 Hill, Fiona and Regine Spector, “The Caspian Basin and Asian Energy Markets”, The Brookings Institution, No. 8 Conference Report, September 2001, p. 3. 68 BP Statistical Review 2005, p. 16. 69 BP Statistical Review 2005, p. 40 70 “It is still to early [to predict peak oil] but there is no doubt at all that the day of peak production is coming…two early-warning signs of such depletion materialized in early 2004, when Royal Dutch/Shell lowered its estimate of its proven reserves by 20% and oil-industry experts concluded that Saudi Arabia was exhausting its reserves at a faster rate than had previously been assumed.”, Klare, Blood and Oil, p. 184. 63 declining production and that by 2050 we could be out of oil.71 The International Energy Agency does not estimate oil production will peak before 2030. 72 There is wide agreement that global oil consumption is on the rise. While there are debates about supply, there is largely agreement that there is a fine balance between supply and demand, which will be the case for the foreseeable future. The other unique characteristics of oil also influence the supply/demand equation. Concern about the reliability of future oil supplies has moved from a purely economic consideration to a national security issue and the psychological impact of higher oil prices also impacts general public perceptions about scarcity. “Scarcity is often determined by politics rather than, as Brock puts it, the ‘physical limitations of natural resources’.”73 Military Intervention Related to Oil Dependence Since the adoption by U.S. of the Cater Doctrine, the U.S. has built an impressive military presence in the Middle East. The U.S. has military bases in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Kuwait,74 as well as a naval aircraft carrier and three expeditionary strike groups in the Persian Gulf.75 U.S. oil dependence in the region, and increasing U.S. concerns over oil scarcity, have arguably played an important role in U.S. engagement in regional conflicts in the Middle East including the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988, Persian Gulf War in 1991, Afghanistan War in 2001 and the Iraq War in 2003.76 “The Gulf War of 1991 was the first war in modern history fought specifically over oil. It serves as a reminder that as long as hydrocarbon resources remain fundamental to economic growth…there will be a commitment to use force to prevent any single government from controlling the market.”77 The U.S. invasion of Iraq, with the UK, has perhaps been the most controversial of U.S. military actions in the Middle East. Multiple theories exist about the motives behind the U.S. war in Iraq beyond the official U.S. statements about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction program. Both Klare in Blood and Oil, and Le Billon78 examine the possible oil agenda behind the U.S. ‘war on terror.’ Their research points to the potential for an escalation in violent conflict in the Persian Gulf as a result of the U.S.-UK occupation of Iraq. U.S. offensive and defensive military activities in the Persian Gulf region do not fit the classic Homer-Dixon model of grievance motivated conflict. The U.S. actions are more in line with studies of ‘beyond greed and grievance,’ yet arguably the violent Peters, Susanne, “Coercive Western Energy Security Strategies: ‘Resource Wars’ as a New Threat to Global Security”, Geopolitics, Volume 91 (January 20, 2004), p. 194. 72 Key World Energy Statistics 2004, International Energy Agency, p. 48, (http://www.iea.org/dbtwwpd/Textbase/nppdf/free/2004/keyworld2004.pdf),. 73 Elliott, Lorraine, p. 237. 74 Magdoff, Harry and John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, Paul Sweezy, “U.S. Military Bases and Empire”, Monthly Review, Volume 53, No. 10 (March 2002), (http://www.monthlyreview.org/0302editr.htm - accessed November 21, 2005). 75 “U.S. Navy, Around the World Around the Clock: Status of the Navy”, November 22, 2005. (http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/news/.www/status.html - accessed on November 22, 2005). 76 Klare, Blood and Oil, p. 2. 77 Morse, Edward, “A New Political Economy of Oil?”, Journal of International Affairs, Volume 53, No. 1 (Fall 1999), p. 16. 78 Le Billon and El Khatib, entire article. 71 inter-state conflicts in which the U.S. has been involved, coupled with U.S. nonviolent defensive security activities in the region, establish a somewhat more complex conflict dynamic than just ‘resource wars’; with war implying violent conflict. The relationship between the U.S., Syria and Iran has become more complicated as a result of the U.S. invasion and tensions are increasing. The U.S. and UK Governments have accused Syria and Iran of supporting armed Shiia insurgents in Iraq against coalition forces. (SOURCE?) While the tensions are not new, the conflict between the U.S. and Iran and/or the U.S. and Syria could escalate given the significant U.S. military presence in the region. Whether the outcome of the Iraqi invasion was predictable or not, the reality is that the already complex dynamics of both violent and non-violent conflict in the Middle East have been altered and have the potential to become more violent as has been seen in Iraq in 2005. The Geopolitics of Oil Conflict The landscape of non-violent real or potential conflict related to oil dependence is perhaps one of the most interesting areas of study in contemporary international security studies. While entire books have been written on oil dependence dynamics in regions such as the Caucasus’, 79 two examples of current political manoeuvring by states will be highlighted to provide a window into the complexity of underlying political and economic dynamics that could influence conflict: China, energy and balance of power politics80 China has one of the fastest growing economies in the world.81 The Chinese government has made securing energy supplies a national security priority. 82 “As of 2003, China’s three state energy organizations had secured important ties with energy enterprises in more than a dozen countries, including Angola, Burma, Ecuador, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Oman, Peru, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Thailand, Venezuela, and Yemen.”83 The Chinese Government arguably has fewer constraints regarding the types of governments it can negotiate with. Unlike the U.S., Chinese government owned companies do not have to abide by the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, nor are Chinese companies as concerned as U.S. companies might be about working in countries with poor human rights records.84 China’s military budget for 2005 is $29.9 billion (12.9% increase over 2004), representing a doubling since 2000.85 China’s military budget’s expansion has been linked to several issues including securing the energy corridors to China, 79 Forsythe, Rosemarie, The politics of oil in the Caucasus and Central Asia: prospects for oil exploration and export in the Caspian basin, (London: IISS/ Oxford University Press, 1996) and Peimani, Hooman, The Caspian Pipeline Dilemma: political games and economic losses, (Westport: Praeger, 2001). 80 Bader, Jeffry and Leverett,Flynt, “Oil Politics, The Middle East and the Middle Kingdom”, The Financial Times, August 17, 2005. 81 International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, 2004, Figure 1.7 (Real GDP). (http://www/imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2004/02 - accessed on November 21, 2005.) 82 Klare, Blood Oil, p. 169. 83 Klare, Blood Oil, p. 169. 84 Jaffe, Amy Myers and Steven Lewis, “Beijing’s Oil Diplomacy”, Survival, Volume 44, No. 1 (Spring 2002), p. 116. 85 Annual Military Balance Report for 2005-2006, International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 2005 and U.S. Department of Defence Annual Report to Congress on China’s Military, July 2005. tensions with Taiwan, and projection of military power vis-à-vis the U.S. and Russia.86 China’s ‘Blue Water Navy Strategy’ has been characterized as a force projection measure primarily directed at securing China’s energy supply, especially in the South China Sea and the Persian Gulf. 87/88 Ownership rights to offshore oil and gas resources in the South China Sea (SCS) remain largely contested. Six Asian states bordering the SCS have made various territorial claims over the years and according to Klare there were 13 military clashes in the SCS between 1988-1999.89 11 million barrels per day of oil flow through the Straits of Malacca, including the majority of Japan’s oil supplies from the Persian Gulf.90 The U.S. Navy’s 7th Fleet is based in Yokosuka, Japan and has access to ports in the Philippines.91 Multiple journal and newspaper articles in the past two years have drawn a link between China’s military build-up and its drive to secure scarce energy supplies. The South China Sea, according to Michael Klare, is “the area most likely to witness large-scale warfare, because all of the factors associated with resource conflict are concentrated here.”92 China provides an excellent example of a country that has linked its national security policy with energy supplies, just as the U.S. China is not involved in violent overt conflicts for oil supplies at this time. It is, however, engaged in balance of power politics that have the potential to lead to escalation of non-violent conflict (i.e. diplomatic disputes) as well as violent conflicts (i.e. SCS). Russia, China and the U.S. The Russian Government (GOR) is wary of China’s growing interest in energy from the CIS. The GOR is deftly working to strike a balance between maintaining friendly relations with China, while making sure China does not gain what Russia would consider to be too much political leverage in the CIS. To this end Russia has developed a two-pronged engagement strategy. o The GOR is enhancing cooperation with China on oil and gas exploration in Russia’s East Siberian fields that could be shipped by pipeline to China.93 Russia’s military hardware exporter, Rosoboronexport, has sold billions of dollars of equipment to China, including naval vessels.94 o In September 2005, the Chinese National Petroleum Company reached agreement with PetroKazakhstan (PKZ) to purchase the company for $14.8 billion. In early October, however, Russia’s largest oil company, Lukoil, took legal action to block the sale. Lukoil offered to match 86 Le Billon and El Khatib, p. 125. Annual Military Balance Report for 2005-2006, International Institute for Strategic Studies, October 2005 and U.S. Department of Defence Annual Report to Congress on China’s Military, July 2005. 88 Klare, Resource Wars, p. 127. 89 Klare, Resource Wars, p. 124. 90 World Energy Outlook, “Oil Flows & Major Chokepoints: The ‘Dire Straits’,” International Energy Agency, 2004. 91 Klare, Resource Wars, p. 133. 92 Klare, Resource Wars, p. 136. 93 Hill and Spector, p. 8. 94 Blagov, Sergei, “More Russian weapons go to China”, Asia Times, reprinted by Center for Defense Information, January 29, 2003. (http://www.cdi.org/russia/242-16.cfm - accessed on November 22, 2005.) 87 CNPC’s bid and after lobbying by the Russian Ministry of Industry, President Nazerbayev blocked the sale to the Chinese in favour of Lukoil. Russia aims to strike a similar balance with the United States. o The GOR is concerned about the presence of U.S. military bases in the CIS. During the July 2005 meeting of The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), that includes China, Russia and four Central Asian republics, a statement was issued “calling on the United States to set a deadline for the removal of its military bases in Central Asia.”95 In June 2005, Uzbekistan’s President Karimov traveled to China, “where he was welcomed with a ‘golden handshake’ in the form of a $600 million natural-gas development contract.”96 Uzbekistan told the U.S. in June the base would have to be closed in six months.97 As the U.S. Government looks for alternative supplies of oil, the CIS region is attractive, and the U.S. has heavily influenced pipeline politics related to the Caspian Sea for over a decade.98 o Meanwhile, Russia is a U.S. ally in the ‘war on terror’ and has a formal energy cooperation dialogue with the U.S. through the U.S.-Russia Energy Working Group and the U.S.-Russia Energy Commercial Dialogue.99 The energy dialogue was highlighted during the Bratislava Summit in February 2005 by President’s Bush and Putin when they called for “identifying concrete trade and investment opportunities for U.S. and Russian firms.”100 The examples above are meant to illustrate the complexity of the oil equation in geopolitics. Within the period of one year, Russia has re-asserted itself into power politics in the CIS and countered moves by the U.S. to establish a wider military presence in the region, which could have served to help the U.S. gain greater access to oil and gas supplies. At the same time, Russia has endorsed expanding bilateral energy cooperation with the U.S. While the chances of overt U.S.-Russian violent conflict are highly unlikely, the U.S. need to diversify oil supply and its interest in energy security in the Caspian Sea basin, make it likely that non-violent conflict dynamics will continue to place tension on the U.S.-Russian relationship. Given China’s close proximity to CIS countries, and its need for new energy supplies, great power politics will most likely continue to unfold between the U.S. and China as both countries vie for access to scarce oil resources. While direct conflict will likely not Chan, John, “Russia and China Call for Closure of U.S. Bases in Central Asia”, World Socialist Web Site, July 30, 2005. (http://www.wsws.org/articles/2005/jul2005/base-j30.shtml - accessed on November 22, 2005.) 96 Cohen, Ariel, “Washington Grapples with Uzbekistan's Eviction Notice”, EurasiaNet, August 17, 2005, p. 1. (http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/display.article?id=6158 - accessed on November 22, 2005.) 96 Hill, Fiona and Regine Spector, “The Caspian Basin and Asian Energy Markets”, The Brookings Institution, No. 8 Conference Report, September 2001, p. 2. 97 Cohen, p. 3. 98 Hill and Spector, p. 3. 99 “U.S.-Russia Joint Fact Sheet, Bratislava Initiatives”, February 24, 2004. (http://moscow.usembassy.gov/bilateral/print_joint_statement.php?record_id=40 - accessed November 22, 2005.). 100 Ibid. 95 unfold, the potential for the contemporary conflict landscape in the CIS to be shaped by the U.S.-China-Russia political axis is substantial.101 Conclusion As agreed by scholars referenced in this essay, the natural resource of oil does not in and of itself make conflict a certainty. The scarcity and abundance oil, its unique properties, and other strategic, political, economic, cultural and geographical factors, shape contemporary conflict characteristics. Most conflicts in countries with an abundance of oil are intra-state secessionist wars or coups against ruling regimes. Greed over resource rents motivates governments to maintain control over oil fields by using force and coercion. Greed can also become a factor for secessionist groups who are able to finance their operations through illegal access to resource rents. In this case, both greed and grievance influence the conflict, in particular its duration. Grievance related to oil scarcity is driven primarily by state dependence on oil to support economic growth. Conflicts related to dependence on oil are typically interstate and can involve the use of military force but can also be non-violent. In the case of non-violent conflict, the geopolitics of oil manifests through balance of power politics that shapes security policies, political agendas, alliance considerations and military budgets. While oil and gas industry experts disagree widely on their specific projections about the extent to which oil supplying countries will be able to meet demand requirements of oil dependent countries in the next 50 years, most agree the balance between supply and demand is tenuous. Adding to concerns about the balance is that most additional supplies will likely come from conflict prone countries and/or countries in conflict prone regions. Factors beyond supplies of oil in the ground also have the potential to increase the likelihood of scarcity including lack of pipeline, tanker transportation, and refining capacity. Therefore, in conclusion, while research by Le Billon, Collier (et-al) and Ballentine/Sherman point to a preponderance of greed motivated conflict related to natural resource abundance today, as Klare, Le Billon and others agree, in the future, contemporary conflict will be influenced is more likely to be influenced by the scarcity of and dependence on oil as a vital natural resource that will inform security, economic and political policies for decades. 101 Klare, Resource Wars, Chapter 4 (p. 81 – 108).