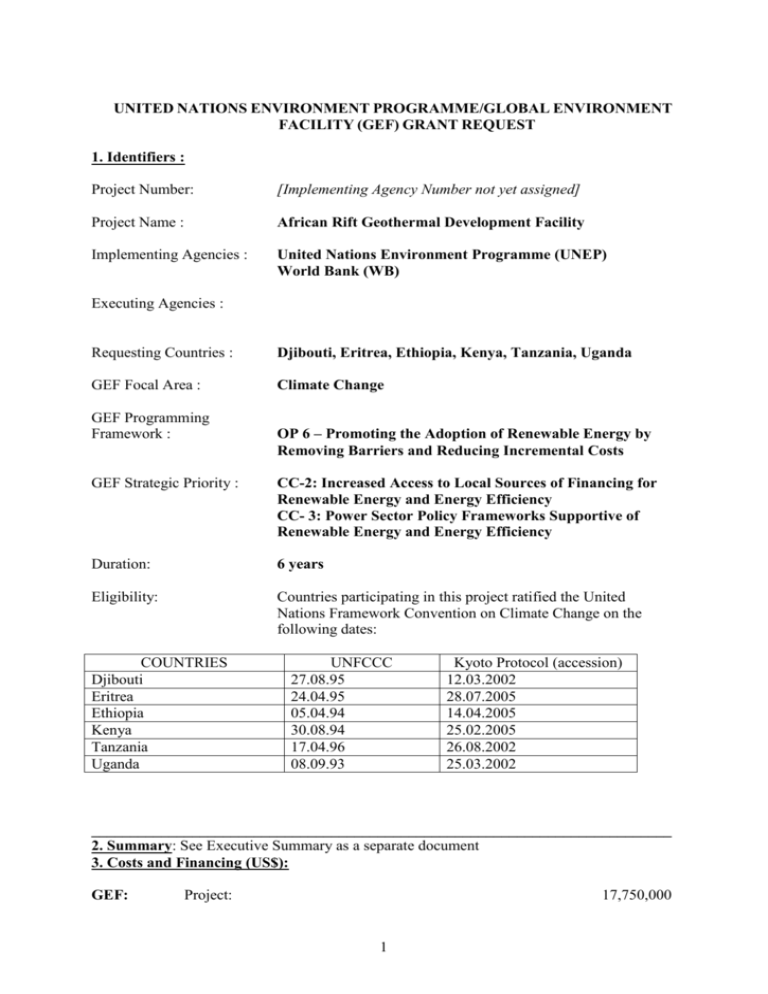

united nations environment programme/global environment facility

advertisement