herrickch3notes

advertisement

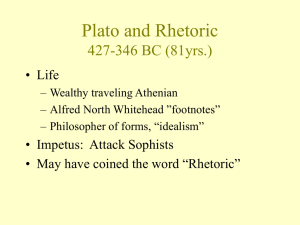

Dr. Katherine Heenan English 472 Spring 2007 Herrick Notes Herrick, James. A History and Theory of Rhetoric: An Introduction. 3rd edition. New York: Allyn and Bacon, 2005 Chapter Three Plato versus the Sophists: Rhetoric on Trial Plato’s views point to the long-standing rivalry btwn rhetoric and philosophy Gorgias offers Plato’s most fierce attack on the Sophists one of Plato’s early dialogues—around 387 BC—mixes elements drawn from actual debates and imagined dialogue Here plato addresses major questions: what is the nature of rhetoric? does rhetoric buy its very nature tend to mislead? what happens to society when persuasion forms the basis of law and justice? scene: Athenian home where Gorgias has just finished an oratorical performance. In the dialogue, Socrates takes on progressively more accomplished opponents o the feeble Gorgias, o the impulsive Polus (G's student) o finally the masterful Callicles Plato criticizes sophists because o they earned money for their teaching o they made exaggered pedagogical claims o they were boastful Rhetoric’s Nature and Uses Round One: Socrates and Gorgias debate the nature of rhetoric Socrates asks Gorgias to define what it is that he does, that is, to define rhetoric. And he asks him to do it in a way that helps to distinguish rhetorical from philosophical discourse: the former produces speeches of praise and blame, the latter answers questions through the give and take of discussion in an effort to arrive at a concise definition, and more broadly, with the intent to understand the subject. Gorgias: rhetoric is valuable because it confers the power to be more convincing on any subject than even experts on the sub under pressure from Socrates he waffles on whether or not he is responsible, as a teacher of rhetoric, for or capable of tacking his students how to use this power beneficially evidence of Plato’s greatest concern about the Sophists—that they profess to teach about justice without any real understanding of justice itself Plato's general argument in Gorgias is that rhetoric as practiced by the Sophists does not embody an adequate conception of justice. This is a dangerous and deceptive activity for the individual and the state, because the Sophists misled their hearers on the most important issue— justice. When a false view of justice was embraced, injustice would prevail. Socrates versus Polus: Rhetoric as Power Round Two: Socrates and Polus debate Polus, Gorgias’s student, enters scene—defending his mentor via the argument that since Socrates doesn't deny that rhetoric confers the power Gorgias says it does, he ought to admit rhetoric is beneficial to the orator because it enables the orator to achieve satisfaction. Socrates counters with fact that if orators exercise power at other's expense, the orators destroy their souls; hence rhetoric is harmful and not beneficial to them Herrick, Ch 3 2 Plato claims that rhetoricians do not know or convey knowledge, viz. that it is not an art or craft (techne) but a mere knack (empeiria, or experience). Socrates adds that its object is to produce gratification. To develop the point, Socrates produces a striking schema divided into care of the body and care of the soul. In the interaction between Socrates and Polus, Plato compares rhetoric to the "knack" of cooking pleasing foods that make one feel better. Cookery, of course, involves no real knowledge of medicine or of restoring health to the body. Activities that achieve an effect without any true knowledge of how the effect is accomplished are not true arts. Rather, they are examples of "flattery" because they "aim at pleasure without consideration of what is best." (465) The true art that restores lost health to a sick soul is called justice, not rhetoric, while the true art that restores lost health to the body is medicine, not cookery. Rhetoric is the counterfeit of the true art of justice. True justice aims at restoring health to a sick soul. Rhetoric as practiced by the Sophists perverts justice by suggesting that actual justice has been achieved when, in fact, only persuasion about justice has occurred. Having cornered Polus into agreeing that anyone who does wrong and is not punished for that wrong is the most wretched among men, Socrates moves to the question of knowledge and what is the great use—the value—of rhetoric. Gorgias, Polus, and Callicles represent various points of view, all of which Socrates, that master/hero philosopher, shows to be false perceptions. Socrates versus Callicles: The Strong Survive Round Three: Callicles—exploiting others is not evil if one is strong enough to do it. Since rhetoric enhances one's strength it is clearly beneficial. Strength here is mental strength and the ability to dominate is the greatest good. Socrates counters that a strong man must do nothing to diminish his good/strength. But rhetoric, by aiding him in satisfying his desires, may lead him to pursue some course that is detrimental to his strength—hence it is not beneficial Socrates: rhetoric is beneficial only when it enables one to bring just punishment upon ones self or a loved one, for correction maintains the health of the soul—which is the greatest good Underlying this discussion is the question of the relation btwn rhetoric and knowledge. Gorgias states rhetoric is concerned only with public, political, and judicial deliberations (which Socrates construes as issues of belief—i.e., issues with probable answers. This enables Socrates to set up a distinction btwn knowledge and belief, the truth and the probable—no moral grounding. He continues this pt. w/Polus who's suggested that the rhetor use rhetoric to achieve his desires at other's expense—which he would not do had he gained knowledge of the just and good along his rhetorical knowledge—Socrates sets up famous opposition btwn cosmetics & Cookery (Sophists) political oratory and rhetoric (forensic oratory) on one hand gymnastics, medicine, legislation, and justice throughout remainder of dialogue, Socrates hammers away at theme of what seems to be true (belief, the probable) and what is true (knowledge, the certain, the transcendent truth) Rhetoric, Socrates posits, is not to be used and abused as the Sophists argue, but is best used as a means of attaining "truth"—that transcendent ideal truth that he as a philosopher has access to. Rhetoric is not to be used, for example, to plead for a defense of injustice since injustices and those who perpetuate them must be punished in order to alleviate their suffering. Instead, rhetoric's great use--its value--is in exposing injustices (in leading us to the truth) and those who commit them all-the-while making certain these folks are not punished so that they truly suffer. — nature—"according to nature" vs "according to convention." C. accuses Socrates of deliberately confusing Polus's use of these terms. C asserts that nature suggests it is right i.e. just for the "better" to have advantage over the worst, for the "stronger" to have advantage over the weaker. . . Herrick, Ch 3 3 Here Socrates demonstrates that Callicles is a slave to convention because he uses rhetoric to get what he wants and advocates that this is right and just for himself and for others to do. Socrates points out that in doing so--in achieving what he desires—Callicles becomes a slave to convention. discusses various types of soul in Phaedrus Plato held that the human soul is complex, consisting of three parts distinguished their characteristic loves: a. One part loves wisdom, b. a second loves nobility and honor, and c. a third part loves appetites or lusts. Individuals are characterized and categorized according to the type of love that dominates in their souls. assigns specific role to a true art of rhetoric in Phaedrus In Phaedrus Plato considers the possibility of a rhetoric used for the good of the individual and of the society. A techne of rhetoric would be an art useful for bringing about justice and harmony is society. A true art of rhetoric would be founded on knowledge of justice and of the human soul. The goal of rhetoric is to establish order in the individual and in the state. The wisdom-loving part of the soul persuades the other two parts to submit to its control. Similarly, wisdom-lovers in the society would also be engaged in the activity of persuading others to submit to their control. The goal of the techne of rhetoric is voluntary submission of the lower parts to the wisdom-lover, a submission producing harmony in the soul as well as the state. Terminology 1. doxa: Greek term for a belief or opinion. Public opinion 2. techne’: Greek term for a true art, which Plato contrasts to a sham art or “knack” 3. pistis: Greek term employed by Plato to mean a mere belief, as contrasted to true knowledge. 4. episteme: Greek term for true knowledge, which Plato felt the Sophists lacked on crucial questions such as justice 5. psyche: Greek term for the mind or soul