The Meaning of Integrated Waste Management

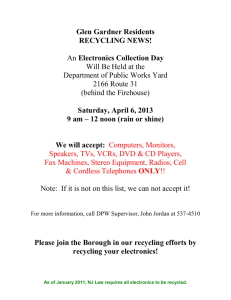

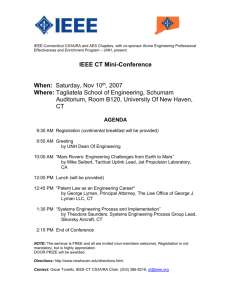

advertisement