Curricular Resources for Child Psychiatry Training in Medical

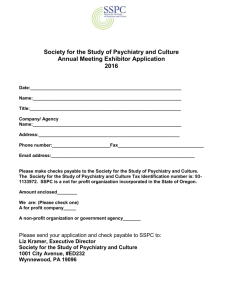

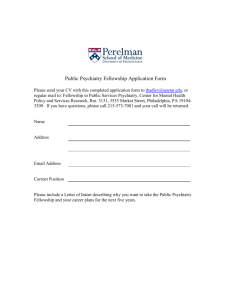

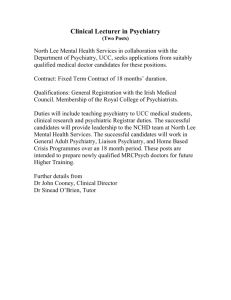

advertisement

Curricular Resources for Child Psychiatry Training in Medical Student Education Steve Schlozman, M.D. I. Formal Child Psychiatry Lecture and Tutorial Experience A. Mandatory as part of the general psychiatry course that occurs in second year of medical school B. Second year course in general psychiatry has multiple functions 1. To teach students about specific psychiatric presentations 2. To introduce students to what we can comfortably surmise about the pathophsyiology of the illnesses we treat. 3. To introduce students to the role of the psychiatrist in the world of medicine. 4. To make students more comfortable with interviewing designated psychiatric patients 5. To make students aware of the prevalence of psychiatric illness in patients who are seeing their physicians in all clinical settings C. These multi-faceted goals allow us to devote one of the 7 formal lectures and one of the 7 formal tutorials that comprise the general psychiatry course entirely to child and adolescent psychiatry D. We therefore introduce the topic of child and adolescent psychiatry after we have covered many of the formal psychiatric disorders that they are likely to encounter and that have their onset in adolescence (mood disorders, anxiety disorders) E. Format – we show a videotaped session of an actual and consented-forteaching interview of an adolescent patient who has been hospitalized but is currently in outpatient psychotherapy and treatment. We use this video as the scaffolding of the lecture. The clinician who conducts the interview on video is present and can tell the students how the patient is doing currently and what changes have been made to her treatment. This allows us as well to stress the importance of inpatient, outpatient, psychotherapy, and psychopharmacological treatments in child patients 1. Patients suffers from Mood Disorder NOS, ADHD, and significant psychosocial stressors. Each of these issues are dealt with both as separate but intertwined issues 2. These diagnoses and the patient’s description of her symptoms allow a three-pronged lecture approach: 1 . We interrupt the video at pre-determined times. i. after first break of video, we discuss normal development (here, a review from their earlier development class) and then places where the patient’s development may been theoretically derailed a. ATTACHMENT b. IMPORTANCE OF DEVELOPMENTAL TRAJECTORY c. DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOPATHOLOGY d. HOW ONE MIGHT ELICIT THESE ISSUES IN A PATIENT INTERVIEW ii. after second break, we cover content a. DEFINE ADHD b. DEFINE PEDIATRIC MOOD DISORDERS c. DISCUSS PEDIATRIC SUICIDALITY d. DISCUSS TREATMENTS e. PRESENT EVIDENCE FOR THESE TREATMENTS f. DISCUSS PATHOPHSYIOLOGY AS IT RELATES TO THE RAPIDLY DEVELOPING BRAIN iii. after third break a. note that regression towards earlier developmental crises is common in medicine b. present a very concrete toolbox for how one might take issues that are germane to child psychiatry and apply them to all patient encounters regardless of age or reason for seeing the doctor E. On tutorial, students then go to three to five different settings and interview at least two patients per three students. This means three students will elect one of the three to conduct the interview with faculty supervision F. Assessment 1. Patient write up in the form of a mental status exam, a developmental assessment and a formulation with proposed treatments 2. Specific questions on the final exam that are directly related to the material presented in class G. CAVEAT: our students just don’t read that much. They study very closely what we show them, but they tend to gloss over the assigned reading. WE THEREFORE TEST THEM PRIMARILY ON WHAT WE CAN SHOW THEM IN CLASS H. CAVEAT: we tell our students that we can’t possibly cover all of child psychiatry in one lecture, and we make ourselves actively available for further shadowing opportunities or research opportunities. J. CAVEAT: we have learned that very few students and indeed very few nonpsychiatrists know what one does to become a child psychiatrist, or know the breadth of what child psychiatrists do. We make this material very concretely available at the beginning of the lecture. II. Formal Electives A. We offer a number of formal and structured 4th year experiences B. These involve inpatient, outpatient, research, emergency, school and C/L settings; most are 4 weeks in duration. Some are two weeks C. We also allow a formal independent project to be designed with faculty mentorship in child psychiatry III. Clerkship Experiences A. We have a 4-week clerkship in psychiatry. To date, we have not been successful in extending that time B. That time is split between C/L and inpatient mostly, with students who want to having the opportunity to shadow faculty in clinic. Some students will ask specifically to shadow a child psychiatrist in clinic or on C/L rounds, and we can virtually meet that request C. There is one formal lecture during the clerkship that attempts to summarize child psychiatry as it relates primarily to the kids they see when they take call in the EW IV. Student Interest Group Topics A. The psychiatry student interest group is active and often has its largest draw (as many as 40 to 60 students, well fed on the lunch that we provide as a bold faced incentive to show-up) when the topics involve child psychiatry. Successful topics have included: 1. Child Psychotherapy 2. Controversies in Psychopharmacology 3. Eating Disorders 4. Child Forensic Issues 5. Advocacy B. When possible, we team up with other student interest groups. For example, there was a very successful forum on substance abuse among youth that involved different approaches from pediatrics, adolescent medicine, and child psychiatry V. Final Thoughts A. Every medical school class has former teachers and/or guidance counselors or something similar. Many of them are looking for ways to continue something akin to the work they were doing but as physicians. We actively seek those students and simply offer to talk with them. B. We very actively tell the students how much fun, and how hard we work, as child psychiatrists. The message we’re aiming for is the experience we all have that the hard work is made possible by the fun and the reward. This is of course no different from the rest of medicine, but the barriers to embracing psychiatry, and perhaps especially child psychiatry, are nuanced and tricky. This approach seems to help with those barriers C. REMEMBER: this is one of the few topics that many of the students will have had some experience already as patients or siblings/friends etc as patients. Some of those experiences will have been great and some not so great. Encouraging discussion around these issues and acknowledging these realities has proved helpful in fostering discussion.