On WordNet Relations

advertisement

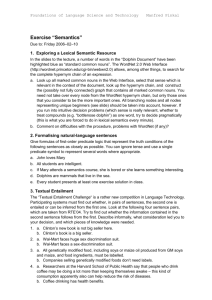

PANEL ON WORDNET RELATIONS WordNet Relations revisited: Panel Discussion on recent approaches to account for various kinds of relations in WordNets and WordNet-like resources PANEL PROGRAMME Introduction by Claudia Kunze (Panel Organizer) Extending GermaNet with syntagmatic relations (Lothar Lemnitzer, University of Tübingen, Germany) Abstract 1 Inducing taxonomies of attribute concepts of adjectves from corpora Aiming at supporting manual development of ontologies (Kyoko Kanzaki, NICT, Japan) Abstract 2 Extending WordNets to all the main POS: specification of cross-POS relations to encode adjectives (Sara Mendes, University of Lisboa, Portugal) Abstract 3 Relations: Are we missing something? (Christiane Fellbaum, Princeton University, USA) Abstract 4 Acquiring semantic relations by harvesting and interpreting noun-noun compounds (Tony Veale, UCD, Ireland) Abstract 5 WordNet and formal ontology (Adam Pease, Articulate Software, USA) Abstract 6 Annotating WordNet Synsets by Sentiment-Related Information: Issues and Potential Solutions (Andrea Esuli, ISTI-CNR, Italy) Abstract 7 Subjectivity mark-up in WordNet: does it work cross-lingually? A case study on Romanian WordNet (Dan Tufis, RACAI, Romania) Abstract 8 ABSTRACTS Abstract 1: Extending GermaNet with syntagmatic relations (Lothar Lemnitzer) I will report about work done for the extension of the German WordNet GermaNet. We are currently extending the WordNet with relations between the verbal head and the head of the direct object. The data have been extracted from a large, partially parsed German corpus. The word pairs have been ranked by the maximum likelihood statistics which indicates the significance of the co-occurrence of both words. Our approach is comparable to that of Bentevogli und Pianta ("Extending WordNet with Syntagmatic Information"), but has a clearer focus on the relations. In my presentation I will shortly explain the application context in which the work is done, depict the current state of the work, and outline our plans for evaluating the extended WordNet. ****************************************************************** Abstract 2 Inducing taxonomies of attribute concepts of adjectves from corpora - Aiming at supporting manual development of ontologies (Kyoko Kanzaki) With the aim of compiling an objective thesaurus of adjectives, we extracted nouns that refer to attribute concepts of adjectives from corpora, manually evaluated the capability to extract the "attribute-instance" relations, and then automatically distributed the obtained attribute concepts on the semantic map. In our experiments we obtained the taxonomic structure (consisting of similarity and hierarchical relations) like a 3D-map in which nouns are distributed according to their similarity. This work is still underway, but the map shows the possibilities of improving the lexicons made by humans. ****************************************************************** Abstract 3 Extending WordNets to all the main POS: specification of cross-POS relations to encode adjectives (Sara Mendes) Extending WordNets to all the main POS involves revision of certain commonly used relations and the specification of new ones. Encoding adjectives in WordNets, for instance, calls for the specification of a number of cross-POS relations. Since the semantic organisation of adjectives seems to be unlike that of nouns and verbs, as this POS does not show a hierarchical organisation (cf. Fellbaum et all (1993) and Miller (1998)), in WordNet.PT we use a small set of semantic relations mirroring adjectives definitional features in the database. It is undeniable that important structural information can be extracted from the hierarchical organisation of lexical items, namely of nouns and verbs. However, extending WordNets to all the main POS involves revision of certain commonly used relations and the specification of several cross-POS relations. Some of the relations used in WordNet.PT are semantic relations introduced in Princeton WordNet, but there are also some new pointers, which allow a strongly empirically motivated encoding of adjectives in the database. These relations, not only allow us to make adjective classes emerge, but they also conform to some complex phenomena (cf. Marrafa (2005) and Marrafa & Mendes (2006) for a detailed discussion on representing and encoding LCS deficitary verbs in WordNet-like lexica). As shown by word association tests, antonymy is a basic relation in the organisation of descriptive adjectives. Nonetheless, this relation does not correspond to conceptual opposition, which is one of the semantic relations generally used for the definition of adjective clusters. We argue that conceptual opposition does not have to be explicitaly encoded in WordNets, as it is possible to infer it from the combination of synonymy and antonymy relations. Still with regard to descriptive adjectives, and to put it somewhat simplistically, these adjectives ascribe a value of an attribute to a noun. Attributes are generally lexicalised by nouns. Hence we use a cross-POS relation to link each descriptive adjective to the noun lexicalising the attribute it modifies. This generally corresponds to the is a value of/attributes relation, used in Princeton WordNet. We use a different label for this semantic relation to make it more straightforward to the common user: charaterises with regard to/can be characterised by. As to relational adjectives, these entail more complex and diversified relations between the set of properties they introduce and the modified noun, often pointing to the denotation of another noun. In order to encode this relation between the relational adjective and the noun which lexicalises the set of properties the adjective points to, we use the is related to semantic relation. This small set of relations allows us to encode the basic features of property ascribing adjectives in WordNets, while making it possible to derive membership of encoded adjectives to the descriptive and relational adjective classes, from the relations expressed in the network. Another issue regarding adjectives is that they have a rather sparse net of relations. We introduce a new relation to encode salient characteristics of nouns, often expressed by adjectival expressions: is characteristic of/has as a characteristic to be. Although we can discuss the status of this relation in terms of lexical knowledge, it is undeniable it regards crucial information for many WordNet-based applications, namely those using inference systems. Also, as the network becomes denser, it contributes to richer and clearer synsets. ****************************************************************** Abstract 4 Relations: Are we missing something? (Christiane Fellbaum, joint work with Jordan Boyd-Graber, Daniel Osherson, Rob Schapire) Although many semantic and lexical relations have been proposed for WordNets in many languages, one might still wonder whether important connections that are intuitively obvious are overlooked. For example, WordNet has no way to link between members of such pairs as "Thanksgiving" and "turkey," "dollar" and "green," "chopstick" and "Chinese restaurant." Purely statistical corpus analyses could find some, but not all such intuitively related pairs and would moreover identify many spurious ones. We performed an experiment aimed at increasing WordNet's connectivity by identifying syntagmatic links among synsets in ways that that did not introduce biases and limitations inherent to traditional, systematic, introspectively defined relations. We collected human ratings that reflect the assiociative strength among frequent and salient concepts. We obtained directed and weighted ratings of similarity for concept pairs. Comparing the results with standard measures of semantic similarity, we found that our evocation method captures similarities that elude these measures. The results raise questions as to the nature of semantic relations, semantic similarity, and human conceptual organization. ****************************************************************** Abstract 5 Acquiring semantic relations compounds (Tony Veale) by harvesting and interpreting noun-noun A noun-noun compound is a noun-phrase in which the underlying semantic relation has been elided, as in "pepper mill", "pizza oven" and "claw hammer". Though WordNet contains a substantial number of noun compounds, this set is just a tiny fragment of the space of compounds in common English usage. Moreover, WordNet does not provide a semantic interpretation for the compounds it contains (though WordNet's meronymy network can be used to understand some part-whole compounds, such as "car engine"). By using corpus-based techniques to interpret common noun-noun compounds, we can augment WordNet in a variety of ways: first, by acquiring new compound lexical entries; second, by acquiring semantic interpretations for these compounds, from which simple textual glosses can be automatically generated; and thirdly, by acquiring specific semantic relations (such as "X grinds Y" for "pepper mill") to connect specific word senses. Since even highly specific nouns like "knife" exhibit different properties in different contexts (e.g., a knife can be used to cut, carve, spread, serve and even paint), we argue that noun compounds provide the best context in which to understand the relational potential of nouns. ****************************************************************** Abstract 6 WordNet and formal ontology (Adam Pease) This short talk will discuss the distinctions between formal ontology and WordNet. Although the hierarchical organization implicit in word senses looks very much like an ontology, it is in fact very different. Also discussed will be the different criteria for inclusion of nodes and arcs (synsets and relations) in both a lexical product and a formal ontology. The talk will present specific results from the ongoing effort to map the Suggested Upper Merged Ontology and WordNet. ****************************************************************** Abstract 7 Sentiment analysis for WordNet (Andrea Esuli) Many works in sentiment analysis have focused on the problem of subjectivity detection, at various levels: from terms (or term senses), as in the automatic annotation of lexical resources, to fragments of text, as in opinion extraction, to entire documents, as in sentiment classification. At all these levels, the two dimensions that have been investigated more actively are polarity ("positive/negative") and force ("strong/mild/weak" expression of positivity or negativity). In the SentiWordNet project we made a first attempt at automatically adding information concerning these two dimensions to WordNet. In another, more recent research we have explored a further dimension of subjective language, i.e, attitude type, which distinguishes, for example, between moral appreciation ("honest") and aesthetic appreciation ("beautiful"). We think that endowing WordNet with annotations pertaining to these three dimensions (polarity + force + attitude type) would make WordNet an even more invaluable resource for sentiment analysis. Adding this information to WordNet would not be an easy task, for at least two reasons. One is the sheer size of the resource; this might call, at least initially, for a semiautomatic approach, on the line of the SentiWordNet or of the "WordNet Evocation" projects. The other is the choice of the taxonomy of sentiment types, which needs to compromise between conceptual subtlety and real-world applicability. For our recent work on attitude type we have adopted a taxonomy of attitude types originally defined in Martin and White's Appraisal Theory; however, other potentially interesting alternatives have been developed, e.g. in the EU-funded Simple project. However, we conjecture that even this three-dimensional specification of the sentimentrelated properties of synsets might not be sufficient for application purposes, at least for some parts of speech. For example, it is conceivable that a verb's polarity should not be characterized as positive or negative tout court, but that a distinction should be made For instance, the verbs "torture" and "discard" both have a negative slant; however, while "torture" casts a negative character on the subject of the action (and on the action itself), "discard" typically casts a negative character on the direct object of the action. Such distinctions should be accounted for in a lexicon, especially in order to make it useful for opinion extraction applications. ****************************************************************** Abstract 8 Subjectivity mark-up in WordNet: does it work cross-lingually? A case study on Romanian WordNet (Dan Tufis) The textual information on Web can be roughly classified as facts and opinions (or subjective assessments). The subjectivity analysis is currently a research topic with many applications in so-called social net for finding users' personal experiences and opinions on various subjects, from commercial products to political events. Word-of-mouth on the Web is taken seriously by policy/decision makers. There are various ways to model the processes of opinion mining and opinion classifications and different granularities at which these models are defined (documents vs. sentences). For instance, in reviews classification one would try to assess the overall sentiment of an opinion holder with respect to a product (positive, negative and possibly neutral). However, the document level sentiment classification is too coarse for most applications and therefore the most advanced opinion miners are considering the sentence level. Thus, a first task becomes detecting the opinionated sentences by classify them as either objective or subjective. Irrespective of the methods and algorithms (which are still in their infancy) used in subjectivity analysis, they exploit the pre-classified words and phrases as opinion or sentiment bearing lexical units. Such lexical units (also called senti-words, polar-words) are manually specified, extracted from corpora or marked-up in the lexicons (as in SentiWordNet). While opinionated status of a sentence is less controversial, its polarity might be rather problematic. The issue is generated by the fact that the polarity of many senti-words depend on context (some time on local context some time on global context. Apparently, bringing into discussion the notion of sense (as Senti-WordNet does) solves the problem but this is not so. For instance the polarity of many modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) depends on the modified lexical unit. Consider the adjective "long" sense no.1 (primarily temporal sense; being or indicating a relatively great or greater than average duration or passage of time or a duration as specified) which is (in SUMO terms) a Subjective Assessment Attribute and has the following subjectivity/polarity mark-up: P:0.0; N:0.125; O:0.875. This would imply that long:1 carries a negative connotation. While this is true for a sequence "the response time is long" this is not the case in "the engine life is long". It would really help to have, in case of modifiers, a special type of relation "Typically-modifies" and to have the subjectivity/polarity mark-up attached to this relation. This idea would make a distinction between words which intrinsically bearing a specific subjectivity/polarity and the words the polarity of which should be relationally considered. A distinct issue is related to cross-lingual validity of the Senti-WordNet annotation. We claim that given that lexical semantics is not culturally-unbound, mechanical transfer of the subjectivity mark-up from the English synsets to other's language translation equivalence synsets might be problematic. For instance, (cf Kim & Myaeng, NTCIR 2007) “a sentence in Japanese, reporting on a rapid merge of two companies should be judged to have negative sentiment whereas the same kind of activities in the US would be a positive event”. In spite of this, we argue that Senti-WordNet is a very useful resource, which requires carefully designed methodologies and algorithms (well beyond the bag-of words current practices) able to fully exploit the sentiment annotations. Our experiments in Romanian, although in an early phase, show that the majority of subjectivity annotations (especially those for nouns and verbs) do hold cross-lingually.