Hatshepsut (throne name Maat-ka-re) and the three

advertisement

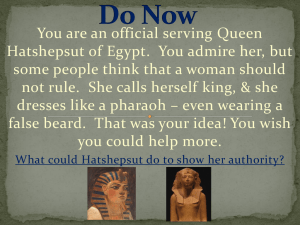

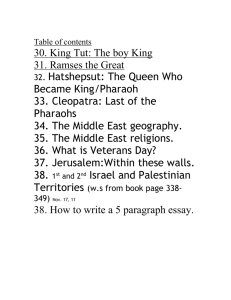

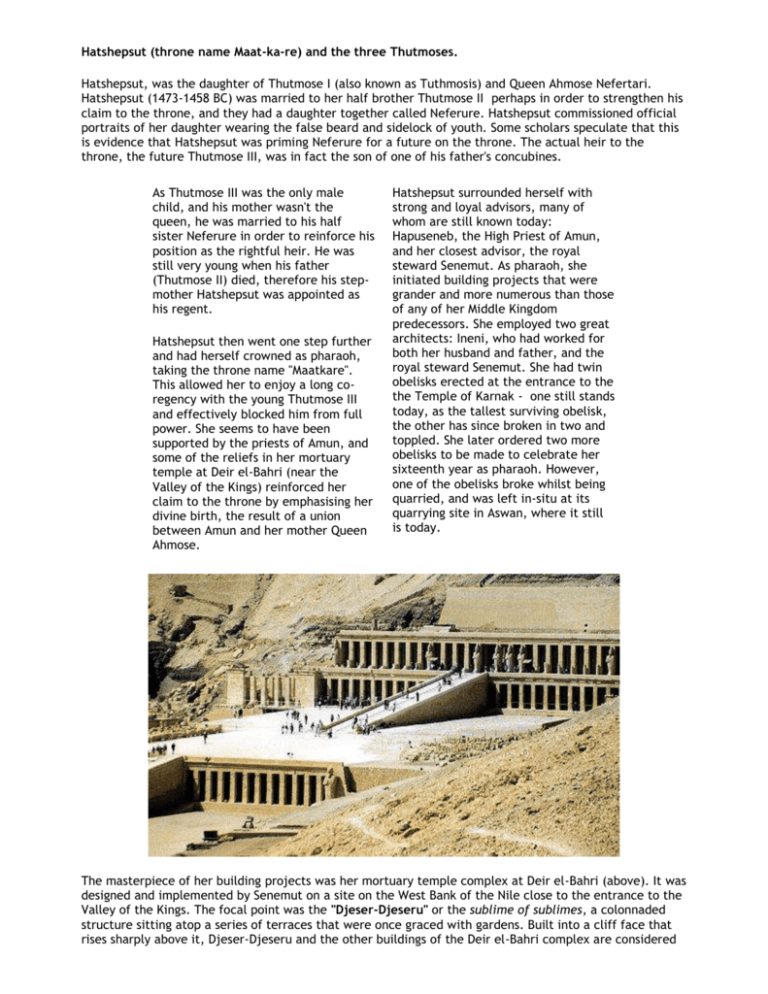

Hatshepsut (throne name Maat-ka-re) and the three Thutmoses. Hatshepsut, was the daughter of Thutmose I (also known as Tuthmosis) and Queen Ahmose Nefertari. Hatshepsut (1473-1458 BC) was married to her half brother Thutmose II perhaps in order to strengthen his claim to the throne, and they had a daughter together called Neferure. Hatshepsut commissioned official portraits of her daughter wearing the false beard and sidelock of youth. Some scholars speculate that this is evidence that Hatshepsut was priming Neferure for a future on the throne. The actual heir to the throne, the future Thutmose III, was in fact the son of one of his father's concubines. As Thutmose III was the only male child, and his mother wasn't the queen, he was married to his half sister Neferure in order to reinforce his position as the rightful heir. He was still very young when his father (Thutmose II) died, therefore his stepmother Hatshepsut was appointed as his regent. Hatshepsut then went one step further and had herself crowned as pharaoh, taking the throne name "Maatkare". This allowed her to enjoy a long coregency with the young Thutmose III and effectively blocked him from full power. She seems to have been supported by the priests of Amun, and some of the reliefs in her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri (near the Valley of the Kings) reinforced her claim to the throne by emphasising her divine birth, the result of a union between Amun and her mother Queen Ahmose. Hatshepsut surrounded herself with strong and loyal advisors, many of whom are still known today: Hapuseneb, the High Priest of Amun, and her closest advisor, the royal steward Senemut. As pharaoh, she initiated building projects that were grander and more numerous than those of any of her Middle Kingdom predecessors. She employed two great architects: Ineni, who had worked for both her husband and father, and the royal steward Senemut. She had twin obelisks erected at the entrance to the the Temple of Karnak - one still stands today, as the tallest surviving obelisk, the other has since broken in two and toppled. She later ordered two more obelisks to be made to celebrate her sixteenth year as pharaoh. However, one of the obelisks broke whilst being quarried, and was left in-situ at its quarrying site in Aswan, where it still is today. The masterpiece of her building projects was her mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahri (above). It was designed and implemented by Senemut on a site on the West Bank of the Nile close to the entrance to the Valley of the Kings. The focal point was the "Djeser-Djeseru" or the sublime of sublimes, a colonnaded structure sitting atop a series of terraces that were once graced with gardens. Built into a cliff face that rises sharply above it, Djeser-Djeseru and the other buildings of the Deir el-Bahri complex are considered to be among the great buildings of the ancient world. Expeditions to The Land of Punt During her reign there was renewed building activity at Thebes and elsewhere, culminating in her mortuary temple as probably the finest of her buildings. In the temple, reliefs tell of the transport of two enormous obelisks from the quarries at Aswan to the temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak, and trading expeditions to the land of Punt ("land of the god", a region of East Africa whose precise location today is unknown) Byblos (ancient coastal town in modern Lebanon, 40km north of Beirut) and the Sinai (peninsula situated between Egypt and the levant). The temple reliefs include detailed depictions of the expedition on its second terrace, including the sea journey and even the reception offered by the chief of Punt. This depictions shows a bearded chief, accompanied by his excessively large queen who has a pronounced curvature of the spinal column. Beehive shaped houses on stilts The bearded chief and his large wife Punt was the source of many exotic products such as gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory, slaves and wild animals such as monkeys and baboons. As a distant and foreign land, Punt acquired an air of fantasy, and as such is mentioned in some narrative tales and poems from the Middle and New kingdoms. The Royal Beard Monuments of Hatshepsut frequently portray her in kingly costume and the famous royal "false beard", often referring to her as though she were male (probably in accordance with the accepted decorum of kingship). When Thutmose III reached maturity he eventually became the sole ruler, but it is unclear whether Hatshepsut simply died or had to be forcibly removed from power. After her death, many of her reliefs sustained damage, where attempts were made to remove her name from them. It was originally thought that Thutmose III had immediately set about removing his stepmother's name from the monuments as retribution for her seize of power, but it is now known that this did not actually happen until considerably later in his reign. Hatshepsut's name was also omitted from subsequent king lists, indicating that her reign was perhaps considered by some to have been inappropriate and contrary to tradition. Although a tomb had been prepared for her in the Valley of the Kings (discovered by Howard Carter in 1903) there is no evidence that it was ever used for her burial. She may have been buried in an earlier tomb in the cliffs to the south of Deir el-Bahri which had been constructed before her rise to the throne. “Hatshepsut”. Egyptology Online. March 19 2009, http://www.egyptologyonline.com/hatshepsut.htm Great Lives from History: The Ancient World, Prehistory-476 C.E. Hatshepsut BORN: c. 1525 B.C.E.; probably near Thebes, Egypt DIED: c. 1482 B.C.E.; place unknown EGYPTIAN QUEEN (R. C. 1503-1482 B.C.E.) Governing in her own right, Hatshepsut gave to Egypt two decades of peace and prosperity and beautified Thebes with temples and monuments. AREA OF ACHIEVEMENT Government and politics EARLY LIFE Hatshepsut (hat-SHEHP-sewt), or Hatshopsitu, was the daughter of Thutmose I and his consort (the Egyptian title was “great royal wife”) Ahmose. Little is known of Hatshepsut’s early life. Although Thutmose I was the third king of the powerful Eighteenth Dynasty, he was probably not of royal blood on his mother’s side; the princess Ahmose, however, was of the highest rank. During the period in Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom (from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Dynasty; c. 1570-c. 1069 B.C.E.), royal women began to play a more active role in political affairs. Among her titles, the pharaoh’s chief wife was called the “divine consort of Amen” (Amen was one of the principal Theban deities). Being the wife of a god increased her status, and her children were given a certain precedence over the children of minor wives or concubines. In addition to Princess Hatshepsut, at least two sons were born to Thutmose I and Ahmose, but both of them died young. The male line had to be continued through a third son, born to a minor wife, who was married to his half sister, Hatshepsut. Thutmose II’s claim to the throne was strengthened by this marriage; he succeeded to the throne around 1518. A daughter, Neferure, was born of this union, but apparently no son was born. The ancient records are fragmentary and at times obscure, but there is evidence that Thutmose II was not very healthy and thus his reign was short, ending around 1504. Once more, there was no male of pure royal blood to become pharaoh; thus, the title passed to a son of Thutmose II by a concubine named Isis. This boy, also named Thutmose, was at the time of his father’s death between the ages of six and ten and dedicated to the service of the god Amen at the temple at Karnak. Because he was underage, the logical choice as regent was his aunt Hatshepsut, now the queen mother. LIFE’S WORK Hatshepsut soon proved to be a woman of great ability and large ambitions. The regency was not enough for her; she wanted the glory of being called pharaoh as well as the responsibility for Egypt and the young king. To realize this desire, however, seemed impossible. There had never been a woman pharaoh—only a man could assume that title, take a “Horus name,” and become king of Upper and Lower Egypt. For a time Hatshepsut looked for possible allies, finding them among the various court officials, the most notable being the architect and bureaucrat Senmut (or Senenmut) and among the priests of Amen. By 1503 her moment had come. Accompanied by young Thutmose, she went to Luxor to participate in one of the great feasts honoring Amen; during the ceremonies, she had herself crowned. There was no question of deposing Thutmose III, but he was, in effect, forced to accept a coregency in which he played a lesser part. To justify this unique coronation, Hatshepsut asserted that she had been crowned already with the sanction of her father the pharaoh. To support this claim, an account was given of her miraculous birth, which was later inscribed at her temple at Dayr el-Bahrī on the west bank of the Nile River. According to this account, Amen himself, assuming the guise of Thutmose, had fathered Hatshepsut. With the approval of both a divine and a human parent, none could oppose the new pharaoh’s will, while Thutmose remained a child and the army and the priests supported her. Hatshepsut did not merely assume the masculine titles and authority of a pharaoh; she ordered that statues be made showing her as a man. In the stylized portraiture of Egyptian royalty, the king is usually shown barechested and wearing a short, stiff kilt, a striped wig-cover concealing the hair, and a ceremonial beard. The number of statues commissioned by Hatshepsut is not known, but in spite of later efforts by Thutmose III to blot out the memory of his hated relative, several examples exist, showing Hatshepsut kneeling, sitting, or standing, looking as aloof and masculine as her predecessors. Neferure, daughter of Hatshepsut and Thutmose II, was married to Thutmose III. This marriage served the dual purpose of strengthening the succession and binding the king closer to his aunt, now his mother-in-law. Hatshepsut then focused her attention on domestic prosperity and foreign trade, activities more to her personal inclination than conquest. Throughout Egypt an extensive building program was begun. At Karnak four large obelisks and a shrine to Amen were built. A temple was also constructed at Beni-Hasan in Middle Egypt. Several tombs were cut for her, including one in the Valley of the Kings. Her inscriptions claim that she was the first pharaoh to repair damages caused by the Hyksos, Asian invaders who had conquered Egypt in the late eighteenth through mid-sixteenth centuries B.C.E. with the aid of new technologies, such as war chariots pulled by horses. The usurpation of these foreign kings was an unpleasant and recent memory to the proud, self-sufficient Egyptians; Hatshepsut’s restorations probably increased her popularity. Larger version (93K) The crowning architectural triumph of her reign was her beautiful funerary temple at Dayr el-Bahrī. Built by Senmut, her chief architect and adviser, it was constructed on three levels against the cliffs; the temple, a harmonious progression of ramps, courts, and porticoes, was decorated in the interior with scenes of the major events of the queen’s reign. Probably the most interesting of the achievements so portrayed was the expedition sent to the kingdom of Punt, located at the southern end of the Red Sea. As the story is told, in the seventh or eighth year of her reign, Hatshepsut was instructed by Amen to send forth five ships laden with goods to exchange for incense and living myrrh trees as well as such exotic imports as apes, leopard skins, greyhounds, ivory, ebony, and gold. Pictured in detail are the natives’ round huts, built on stilts, and the arrival of the prince and princess of Punt to greet the Egyptians. The portrait of the princess is unusual because it is one of the rare examples in Egyptian art in which a fat and deformed person is depicted. In addition to the voyage to Punt, Hatshepsut reopened the long-unused mines of Sinai, which produced blue and green stones. Tribute was received from Asian and Libyan tribes, and she participated in a brief military expedition to Nubia. Despite the latter endeavors, Hatshepsut’s primary concern was peace, not imperialistic expansion. In this regard, her actions were in sharp contrast to those of her rival and successor Thutmose III, who was very much the warrior-king. It would not be sufficient, however, to explain Hatshepsut’s less aggressive policies on the basis of her sex. Traditionally, the Egyptians had been isolationists. Convinced that their land had been blessed by the gods with almost everything necessary, the Egyptians had throughout much of their earlier history treated their neighbors as foreign barbarians, unworthy of serious consideration. Hatshepsut and her advisers seem to have chosen this conservative course. As Hatshepsut’s reign continued, unpleasant changes began to occur. Her favorite, Senmut, died around 1487. In addition to the numerous offices and titles related to agriculture, public works, and the priesthood, he had also been named a guardian and tutor to Neferure. No less than six statues show Senmut with the royal child in his arms. At the end of his life, he may have fallen from favor by presuming to include images of himself in his mistress’s temple. Most were discovered and mutilated, presumably during Hatshepsut’s lifetime and with her approval—her names remained undisturbed. Princess Neferure died young, perhaps even before Senmut’s death, leaving Hatshepsut to face the growing power of Thutmose III. The king had reached adulthood: He was now the leader of the army and demanded a more important role in the coregency. His presence at major festivals became more obvious, although Hatshepsut’s name continued to be linked with his until 1482. It is not known exactly where or when Hatshepsut died or whether she might have been deposed and murdered. That her relations with her nephew and son-in-law were strained is evident from the revenge Thutmose exacted after her death: Her temples and tombs were broken into and her statues destroyed. Her cartouches, carved oval or oblong figures that encased the royal name, were erased, and in many cases her name was replaced by that of her husband or even of her father. She was eliminated from the list of kings. Thutmose III ruled in her stead and did his best to see that she was forgotten both by gods and by men. SIGNIFICANCE The nature and scope of Hatshepsut’s achievements are still subject to debate. Traditional historians have emphasized the irregularity of her succession, the usurpation of Thutmose III’s authority, and her disinterest in military success. Revisionist studies are more generous in assessing this unique woman, praising her for her promotion of peaceful trade and her extensive building program at home. Her influence throughout Egypt, though brief and limited only to her reign, must have been profound. The considerable number of temples, tombs, and monuments constructed at her command would have provided work for many of her subjects, just as surely as the wars of her father and nephew provided employment in another capacity. Art, devotion to the gods, and propaganda were inextricably mingled in the architectural endeavors of every pharaoh. Hatshepsut’s devotion to the gods, especially the Theban deity Amen, and her evident need to justify her succession and her achievements enriched her nation with some of its finest examples of New Kingdom art. Controversial in her own lifetime and still something of a mysterious figure, Hatshepsut continues to inspire conflicting views about herself and the nature of Egyptian royalty. She was a bold figure who chose to change the role assigned to royal women, yet at the same time, she seems to have been a traditionalist leading a faction that wanted Egypt to remain self-sufficient and essentially peaceful. Perhaps that was yet another reason that she and Thutmose III were so much at odds. His vision of Egypt as a conquering empire would be that of the future. She was looking back to the past. FURTHER READING Aldred, Cyril. The Development of Ancient Egyptian Art from 3200 to 1315 B.C. Reprint. London: Academy Editions, 1973. The title indicates the focus of the work. There are more than fifteen plates depicting Hatshepsut, other members of her family, and her adviser Senmut. Detailed explanations accompany each picture, and there is also an index and a bibliography. “Egypt Completes Repairs to Pharaonic Sites.” The New York Times, December 26, 2001, sec. A, p. 4. Describes the reopening in Egypt of part of the temple of Queen Hatshepsut, which contains reliefs of the pharaoh making offerings to the gods. Gardiner, Sir Alan. Egypt of the Pharaohs. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969. Although a lengthy study, Gardiner’s work is engagingly written, with balanced views of both Hatshepsut and her successor, Thutmose III. Provides a good background for the less knowledgeable reader. Includes an index, a bibliography, and a comprehensive chronological list of kings. Illustrated. Nims, Charles F. Thebes of the Pharaohs: Pattern for Every City. New York: Stein and Day, 1965. The city of Thebes was extremely important to Hatshepsut and her family as both a political and a religious center. This book is helpful because it places the queen in her environment. Tyldesley, Joyce A. Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh. New York: Viking, 1996. In this biography, archaeologist Tyldesley dismisses speculative attempts made by some scholars to suggest that Hatchepsut was a transvestite. This book will be primarily of interest to specialists. Wenig, Steffen. The Woman in Egyptian Art. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969. This book is extremely well illustrated with both color and black-and-white photographs as well as drawings. The period covered is from c. 4000 b.c.e. to c. 300 c.e. Contains a chronology and an extensive bibliography and is written for the general reader. Wilson, John A. The Burden of Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951. This extensive study is both detailed and well written; it deals with the importance of geography to Egypt. Includes maps, a bibliography, illustrations, and a chronology of rulers. Wilson’s analysis of political theories and discussion of possible motivations of the pharaohs is very useful in understanding the conflict between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. RELATED ARTICLES IN GREAT LIVES FROM HISTORY: THE ANCIENT WORLD c. 1570 b.c.e., New Kingdom Period Begins in Egypt; From c. 1500 b.c.e., Dissemination of the Book of the Dead. Dorothy T. Potter Hatshepsut Hatshepsut was born in the 18th Dynasty. This Dynasty is also referred too as the New Kingdom. Hatshepsut entered this world as the daughter of royal parents. Her father was Tuthmosis I and ruled Egypt for approximately 12 to 14 years. Her mother was Ahmes. Ahmes was the sister of Amenophris I (Pharaoh who ruled Egypt for 21 years). In addition to Hatshepsut, Tuthmosis I and Ahmes had a son. They named him Anenemes. By birthright, Anenemes should have inherited the throne as the son of Tuthmosis I and Ahmes; however, he never became king. Hatshepsut, on the other hand, went on to rule Egypt in later years for approximately 21 years. Hatshepsut ruled Egypt between 1479-1458/57. She ruled in a time when women were allowed to own property and to hold official positions. They were given rights to inherit from deceased family members and were allowed to present their cases in court. Women of Ancient Egypt had more freedom then other ancient cultures such as Greece where women were expected to stay home. After the death of Hatshepsut’s father (Tuthmose I), her half brother (Tuthmose II) succeeded the throne. As it was customary in royal families, the oldest daughter of the pharaoh would marry a brother to keep the royal blood lines intact. Therefore, Hatshepsut married her half brother. Tuthmose II was the son of one of her father’s lesser wives (Mutnofret); however, his reign would be short and his life short-lived. It may have been that Tuthmose II died of an illness and thus held the throne only for 14 years. During their marriage, Hatshepsut and Tuthmose II were not able to produce a male heir but rather had a daughter whom they named Neferure. In later years, it appears that Neferure may have been married to her half brother (Tuthmose III); much like her mother had married a half brother in previous years. Tuthmose III was the son of Tuthmose II (Hatshepsut’s husband) and one of his royal concubines named Isis. This blood line made Tuthmose III a stepson to Hatshepsut. Because Tuthmose III was very young when his father died, Hatshepsut became a co-regent and ruled right along side the young stepson. It appears that within the second or third year of this co-regency reign, Hatshepsut proclaimed herself king with complete titles. She would be known as Maatkare (Matt is the ka of Ra) and also Khnemet-Amun-Hatshepsut (She who embraces Amun, the foremost of women). After this proclamation, Tuthmosis III would no longer reign as co-regent with Hatshepsut. In order to make Hatshepsut’s proclamation to king more official and more accepting to the Egyptian citizens, she invented a co-regency with her father Tuthmosis I. She even went as far as incorporating this fabricated co-regency into texts and representations. These were found decorating her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. In addition, and also to make things still more official, Hatshepsut dedicated a chapel to her father in her mortuary temple. She hoped to acquire more acceptance as the new ruler of Egypt by changing the beliefs of her people. Hatshepsut was a very unique and intelligent individual. She used various strategies to legitimize her position as pharaoh. Not only did she proclaim herself as pharaoh and fabricate a co-regency with her father (Tuthmose I), but she also tried to make herself more god-like by the invention of stories with the attachment to gods. She did this by making it appear as if the gods had spoken to her and her mother while in she was still in her mother’s womb. Hatshepsut misled her subjects and the uneducated public by indicating that Amon-Ra had visited her pregnant mother at the temple in Deir el-Bahri in the Valley of the Kings. Hatshepsut was unique because she took on several male adornments while she ruled Egypt. Unlike most women of that time, she attached a false beard, wore male clothing, and was depicted in statutes as a pharaoh. She might have done this to make her transition to kingship and the acceptance of the priesthood more convincing. It may be that if she had ruled strictly with a more feminine-looking disposition she may not have been so readily accepted by the masses. Her strategy seemed to work and the priests supported her reign as pharaoh. There were many prominent figures during her reign but there appears to be one person in particular who was probably foremost in her circle. This prominent person was Senenmut who was born of a humble family in Armant. He came to be known as Hatshepsut’s spokesman and steward of the royal family. In addition, he was known as superintendent of the buildings of the God Amun. During the later years, Hatshepsut had obelisks installed in the Temple of Amon-Re at Karnak. Senenmut supervised the transport and erection of these obelisks as well as the mortuary temple that was built for Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. It appears that he must have been very well favored by the Queen as he had a separate tomb constructed close to Hatshepsut’s tomb for himself. He had this second tomb dug out in front of Queen Hatshepsut’s tomb in spite of owning another tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna. During Hatshepsut’s reign, gossip followed the pair as it was suggested that his good fortune was due as a result of his intimate relations with the Queen. To add to this deduction, it was further fueled by the fact that he played a heavy role in the education of Hatshepsut’s only daughter Neferure. His brother, Senimen, also acted as nurse and steward to Neferure and this caused more gossip to run rampant. Several statues were found associating Senenmut with the Princess Neferure. History shows that Senenmut was a prominent figure during three-fourths of Hatshepsut’s reign and possibly after the death of Neferure (it appears that she died around the 11th year of Hatshepsut’s reign), that he fell out of graces with the queen for unknown reasons. Speculation has it that he may have had some kind of alliance with Tuthmosis III (Hatshepsut’s stepson) and this could have led to the demise of their relationship. History also shows that the construction of the famous temple of Deir el-Bahri was most probably started by Tuthmose II and later finished by Queen Hatshepsut. The walls of the temple depict major achievements such as the expedition to Punt near the Red Sea. This trading expedition brought back many riches for the country. To this day, the death of Hatshepsut remains a mystery. It appears that she reigned for fifteen years and her stepson took the throne after her disappearance. It’s also believed that the hatred for his stepmother pushed him to erase the memory, existence, and any depictions of Queen Hatshepsut by destroying any monuments erected during her reign. Although her temple still stands, neither her tomb nor her mummy has ever been found. She has now come to be known as having been the only female pharaoh to erect the most monuments during her reign. Kingtutone.com Hatshepsut (1479 - 1457 BC) Queen Hatshepsut (left) was the first great woman in recorded history: the forerunner of such figures as Cleopatra, Catherine the Great and Elizabeth I. Her rise to power went against all the conventions of her time. She was the first wife and Queen of Thutmose II and on his death proclaimed herself Pharaoh, denying the old king's son, her nephew, his inheritance. To support her cause she claimed the God AmunRa spoke, saying "welcome my sweet daughter, my favourite, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, Hatshepsut. Thou art the King, taking possession of the Two Lands." She dressed as a king, even wearing a false beard and the Egyptian people seem to have accepted this unprecedented behaviour. She remained in power for twenty years and during this time the Egyptian economy flourished, she expanded trading relations and built magnificent temples as well as restoring many others. Eventually her nephew grew into a man and took his rightful place as pharaoh. The circumstances of this event are unknown and what became of Hatshepsut is a mystery. (above) Queen Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el Bahri Hatshepsut's successor became the greatest of all Pharaohs, Thutmose III, "the Napoleon of ancient Egypt." He had her name cut away from the temple walls which suggests he was not overly fond of his auntie. But the fact that she was able to contain the ambitions of this charismatic and wily fellow for so many years, hints at the qualities of her character. (above) Inside the temple (above) Parade' and 'The Army' are etchings made from drawings done at Deir el Bahri. 'The Army' represents a trading expedition to the Land of Punt (thought to be somewhere on the coast of Somalia) and shows Nehsi the Nubian general. http://www.discoveringegypt.com/Hatshepsut.htm Need more information or better quotations? Try the following site: http://www.touregypt.net/18dyn05.htm