Narrative as a mode of thinking, as a structure for organizing our

advertisement

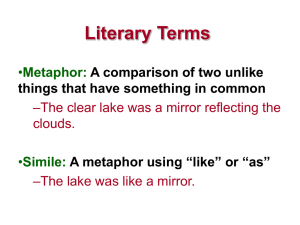

Tellability 2 - sense-making devices The second category of narrative markers involves listeners at a cognitive level in the construction of meaning. These devices require them to participate imaginatively in the story by creating their own mental picture of the story events, bringing it to life and reconstructing the drama of what happened for themselves. Imagery and detail Direct speech Metaphor and metonymy Ellipsis Irony Hyperbole 1 a. Imagery and detail The ability to present a story as a scene in which the listener can participate is an important storytelling skill and a process to which imagery and detail are crucial. In Horses, Max uses detailed sense imagery to bring the listener closer to the narrative – I’ve stroked their manes; the smell of a good horse, I could smell him. Since the tellability of this particular story is based on Max’s knowing more about horses than Lenny, the details are important for the success of the narrative. The image in I’ve stroked their manes resonates with the listener not just because it is detailed but because it justifies the reason for the narrative. The sense imagery also becomes more and more particularised - the smell of a good horse becomes more personalised in I could smell him. I’d look her in the eye is followed later by I’d look her straight in the eye and deep down in her eye. The increased detail acts like the zoom of a camera, taking the listener closer to the image and further into the story. b. Direct speech This narrative strategy introduces narrators’ own words or those of a third party into a story. Although we cannot remember long stretches of talk word for word and verbatim reporting of what has been said in the past is largely impossible, narrators often prefer to use direct speech (Max, they’d say, “There’s a horse there”) rather than indirect speech (They said there was a horse there) when reporting what someone has said. This inherent implausibility of direct speech does not generally affect listeners’ acceptance of a story. On the contrary, in the interests of hearing a good story listeners are willing to suspend their disbelief regarding the fidelity of the reported words to the original. Direct speech is effective because it presents the speech vividly as if the exact words are being spoken, bringing the listener closer to what was said1. Thus in the sentence Max, they’d say, There’s a horse here, he’s highly strung, you’re the only man on the course who can calm him the nominalisation of Max and the use of the deictics you and here in the direct speech create a context which enables listeners to hear the actual words that were spoken, contributing to the overall visualisation of the scene that Max is trying to create. c. Ellipsis Another way of involving listeners is to use an elliptical storytelling style which leaves something out of the narrative, requiring them to take part in constructing the meaning of the narrative and thus contributing to “a sense of involvement through mutual participation in sensemaking” (Tannen 2007). This might be straightforward grammatical abbreviation, such as Max’s omission of subject and verb in the utterance One of the loves of my life. This kind of ellipsis is very frequent in talk and can contribute to the colloquial nature of a story. There is also a more interactional type of ellipsis in which speakers refer only indirectly to what they wish to say through the use of politeness forms (Brown and Levinson 1987). If successful, this “elliptical” form of interaction creates a form of complicity between speakers who can communicate through allusion. Tannen (2007) 1 Although direct speech is common in everyday spoken narratives, it may be less so in literary ones. Tannen (1986), for example, claims that the use of direct speech in narratives is more frequent in ordinary conversation than in literary storytelling. If this is correct, the use of direct speech in a narrative like Max’s could be an exceptional case. 2 also refers to the role of silence as an extreme form of ellipsis - a way representing what is not said (see also the section on pause and silence in 2.3.3). In this respect the pauses in Max’s story can be interpreted as elliptical as he waits for Lenny’s participation in the story which does not come. d. Metaphor and metonymy Figure of speech2 is a general category of words and phrases which require listeners to make non-literal interpretations. The ubiquity of figurative language in spoken discourse has led cognitive linguists to suggest that all language is figurative and that what we consider to be literal is already pre-constituted by figurative thought. For Gibbs (1994) metaphorical thought is the engine of interpretation: “metaphor, and to a lesser extent metonymy, is the main mechanism through which we comprehend abstract concepts and perform abstract reasoning” (Gibbs 1994: 11). This view of metaphor as embracing the production and comprehension of all language means that the traditional distinction between literal and non-literal language, based on the abstract semantic of words rather than on personal knowledge and discourse comprehension processes, is not so clear-cut (Steen 2002). The pervasiveness of metaphor in ordinary talk gives it a different status from other figures of speech such as hyperbole (see below) which signal that talk can be taken non-literally (Edwards 2000). A metaphor can be defined as a set of correspondences between two conceptual domains, while metaphorical understanding involves a process of mapping between these domains (Lakoff 1993). So when Max describes the horses as thundering past the post, he is describing the horses as being noisy without saying so directly. We interpret the expression by analogy with the sound that thunder makes. One concept (thunder) is used to describe another concept (loud noise) and in interpreting this connection we make a conceptual leap between the two. Although the classification of these leaps is fraught with methodological difficulty [Semino, Heywood and Short (ms)], it is argued that it can be derived from linguistic expressions (Steen 2002; Heywood, Semino and Short 2002). The amount and complexity of metaphor in spoken narratives may affect the degree of listener involvement. Gibbs (2006: 44) claims that “conceptual metaphors seem to be ubiquitous in the ways people talk of their experiences”. Stories that contain a lot of non-literal language may require the listener to do more work in constructing the connections between conceptual domains and this increases the degree of listener involvement. As regards complexity, metonymic relations and subclasses of metonymy, such as the part-whole relation of synecdoche, are based on a closer connection with our everyday experience and are arguably easier to interpret. This would imply that speakers might be able to vary the extent to which they use non-literal language to accommodate the listener. However, the question of the amount of cognitive effort required to interpret figurative speech is the subject of intense debate. In an assessment of the evidence from metaphor processing studies Gibbs concludes that there is little evidence to show any difference in processing time for literal and non-literal speech – “the findings of these widely varying studies strongly imply that metaphors are not deviant and do not necessarily take more time to understand” (2006: 46). He suggests that it is not the amount or complexity of metaphorical usage per se which contributes to involvement in stories but whether listeners are familiar with them or not. 2 See Leech (2008: 11ff.) on how linguistic theories can be used to account for figures of speech. 3 e. Irony Emerging from dynamic conversational activity, irony is the result of a violation of conversational expectations (Clift 1999). Its success in storytelling therefore depends on its being correctly interpreted by the listener, who recognises “the markers used to direct the recipient of the message to the right interpretation” (Boutonnet 2006: 28). These markers may occur at the level of prosody, lexis or grammar. For example, irony is often signalled by an intonation pattern which communicates to the listener that an utterance is not to be taken literally. In Horses it is possible to interpret the expression he talks to me about horses as ironic even though there is no marked intonation. The irony is signalled by the fact that Max is addressing Lenny but uses the third person form he as if referring to an imaginary audience, thus creating a distortion of the interactional framework. We therefore interpret he talks to me about horses as meaning “he talks to me about horses but he isn’t qualified to talk to me about horses because I know more about them than he does” and the subsequent Horses story can be interpreted as an attempted justification for this ironic claim. What this example shows is that irony is more closely dependent than metaphor and metonymy on the interactional dynamics between story participants and is designed to provoke an interested response from them. This is confirmed at the end of the story. When Max pauses after the summative phrase I had a gift, a response does not come and he then repeats the expression and he talks to me about horses. This final dig at Lenny does prompt a response from Lenny but it is a polite request to change the subject. f. Hyperbole When Max says I used to live on the course we understand that he is exaggerating. We know he did not actually live there and that all he really wants to say, in a colourful way, is that he used to spend a lot of his time there. Hyperbole then is one of the linguistic devices a speaker might use to exaggerate. The terms “bold exaggeration (Preminger 1974: 359), “overstatement” and “extreme case formulation” (ECF) (Pomerantz 1986) are also used to describe the way that hyperbole operates in discourse. It is important then to distinguish this terminology in order to understand how hyperbole is interactively used in narrative. Edwards (2000) has shown how ECF’s are used in conversation without softening or hedging as markers of speaker attitude and, specifically, to signal investment in what speakers are saying. This “heightening” of the speaker’s attitude shows that they are particularly committed, determined or certain about the stretch of talk to which the ECF is applied. Edwards also argues that these markers serve to signal to a listener that a stretch of talk can be taken non-literally. It is likely that the more they are used in a stretch of narrative, the more committed the speaker is to it and the less literally he/she intends it to be taken. Norrick (2004) distinguishes the ECF from what he calls “non-extreme hyperbole”, arguing that the former is actually a sub-category of hyperbole rather than being a general umbrella term. ECF’s are blatant exaggerations violating Grice’s maxim of truthfulness, and “generally embed extreme expressions in otherwise literalseeming talk”. Max’s you’re the only man on the course who can calm him. I used to live on the course are thus both good examples. The context is literal-sounding but the only man and live are obviously exaggerated. Hyperbole, on the other hand, is less obviously untrue, more image-based and corresponds more closely to the beliefs of the speaker. Unlike ECF’s, hyperbole “ … is surrounded by obviously non-literal talk” (Norrick 2004: 1737). Max’s one of the 4 loves of my life is thus a good example of its non-extreme variety. Speakers often use it in harness with the other markers of narrative described in this chapter. For example, you’re the only man on the course is also in direct speech and includes the marker of intensity only. Norrick (2004) notes how ECF’s are often tied to formulaic expressions and Max is particularly fond of this hyperbolic/formulaic combination. His phrases one of the loves of my life and knew it like the back of my hand are both clichéd and exaggerated at the same time. Hyperbole then is a powerful device which speakers use to “do non-literal” (Edwards 2000) in narrative. It enables the speaker to embellish stories while at the same time reassuring listeners that the embellishment does not have to be taken literally. 5