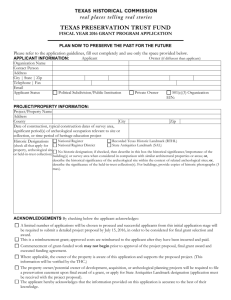

NHL Nomination Study [FORMAT]

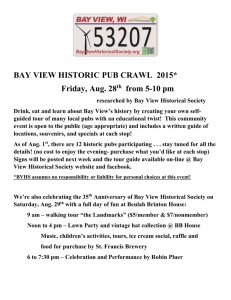

advertisement

![NHL Nomination Study [FORMAT]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007663835_2-aba185b5d3bdfb8bbbad4762958f3a4b-768x994.png)