Breast Cancer in Trinidad

BREAST CANCER IN TRINIDAD

Vijay Naraynsingh*, Ravi Maharaj, Dilip Dan

Department of Clinical Surgical Sciences

The University of the West Indies St. Augustine

*Correspondence to: vnaraynsingh@gmail.com

Breast cancer is the commonest cause of death from cancer among women worldwide and also in Trinidad and Tobago (T&T). (1,2,3) However, in general, the mortality from breast cancer in developing countries is less than that from developed ones. For example, in 2002, breast cancer mortality in India was 10.4 and in Brazil 14.1 compared to 19.0 and 24.3 per 100,000 in the USA and UK respectively (4).

While this pattern is true for many countries, there are some aspects of this disease in Trinidad and Tobago that should concern both patients and practitioners. However, our Caribbean neighbours also record high mortalities from this disease. In the year 2000, Barbados reported a mortality of

34.9, Jamaica 18.3 compared to 19.1 per 100,000 for Trinidad and Tobago (3,5,6). In particular, the increasing mortality in Trinidad and Tobago is noteworthy (3).

Incidence and Mortality

In T&T, we see about 250 new cases per year. This is likely to be an underestimate as not all cases, especially from private institutions, are reported to the Cancer Registry (7).

What is remarkable, however, is that over 33% of new cases are under the age of 50. i.

Breast cancer accounts for about 125 deaths per year. This gives an incidence: death ratio of 2:1. This is quite high compared to data from the developed world. Such a ratio suggests that for every 2 women with breast cancer in T&T one would die from the disease. There are several possible explanations for this dismal prognosis.

Late Presentation .

While it is expected that patients who present with advanced disease will have a poorer prognosis, nearly 80% of our cases have Stage I and II disease at diagnosis

(8). Mammography seems to have made little or no contribution to earlier diagnosis of breast cancer in Trinidad. The report from our National Cancer registry indicates that in the 5 year period 1995-1999, only 1 of 1176 cases was diagnosed by mammography. (7) Worldwide there remains controversy about the value of mammography in early diagnosis (9, 10). Moreover, its relevance to breast cancer care in Latin America and the Caribbean has been questioned by the

Pan Americian Health Organisation (11). In that paper, Robles and Galanis state “… most of their breast cancer screening policies are not justified by available scientific evidence. Moreover, as seen, by relatively high mortality:

2

incidence ratios, breast cancer cases are not being adequately managed in many

Latin America and the Caribbean countries. Before further developing screening programs, these countries need to evaluate the feasibility of designing and implementing appropriate treatment guidelines and providing wide access to diagnostic and treatment services” (11). ii. Younger age at presentation.

It is generally held that breast cancer in the young is more aggressive and has a poorer prognosis than when it presents in the later life. In Trinidad and Tobago,

34% of cases are under the age pf 50 at diagnosis. In the developed world only

15-20% of cases are in this age group. iii. Commoner in Blacks

It is quite clear that locally, Blacks are more prone to breast cancer than other racial groups. Data from our Cancer Registry indicate that Blacks accounted for

45.9%, Indians for 27.5%, Mixed 14.7% and others for 12% (12). Data from

USA suggest that breast cancer in Blacks is associated with a poorer prognosis than whites. Although it was initially thought that this might be explained by later presentation or disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances among Blacks, it is now recognized that even for the same stage and availability of care, breast cancer in Blacks carries a poorer prognosis than in other ethnic groups. There are some data to suggest that the biology of the tumour is different in this group

(13,14). iv. Inadequate Health Care Services

There may well be deficiencies in most aspects of breast cancer care in T&T, but it is difficult to obtain hard data to demonstrate these. Some aspects that need to be assessed are as follows:

3

a.

Delays in diagnosis

There are many benign conditions that may be mistaken for breast cancer and vice versa. Thus, both patients and practitioners could suspect that the presenting symptoms and signs are consistent with benign disease resulting in delayed referral to specialist care. Another certain reason is the unjustifiable reliance on mammography for diagnosis in patients presenting with a breast lump. Both patients and practitioners have been falsely reassured by a negative mammogram in these circumstances (15).

Further delay might result from long waiting times for appointment to see the specialist, for biopsy to be done and for pathology results to be obtained. While most practitioners are aware of these factors there are no data to quantify objectively, the relative roles of these factors in contributing to delayed diagnosis but each is certainly relevant and important. b.

Inadequate Definitive Care

Patients frequently experience delays in obtaining definitive surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. There are a variety of reasons for deficiencies of these services but, in general, there are slow and steady improvements in all areas. There is still need for focused multidisciplinary care for the scourge of this disease. c.

Increasing Mortality

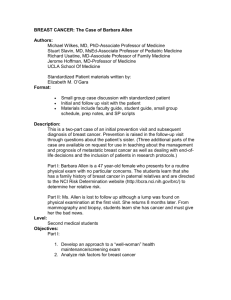

Another area of concern is the steadily increasing mortality from breast cancer in Trinidad and Tobago. This increase has now placed T&T among the countries with the highest mortality from breast cancer (Fig 1). A 35year study of mortality from this disease showed an almost linear, steady increasing death rate from about 10 per 100,000 in 1970 to 25 per 100,000 in 2004 (3) (Fig 2). The increasing mortality can be partly explained by an increasing incidence of the disease. However, in many developed countries, although there is in fact an increasing incidence, they have managed to achieve a decreasing mortality by early diagnosis and efficient

4

delivery of multidisciplinary care(16). In the UK, USA and Canada, there was a gradual increase in mortality up to the mid – late 1980’s but since then there has been a steady decline in death rate (16,17,18). Most of this decline seems to be related to early detection and advances in treatment; it bears little relation to mammography and the decline antedated the establishment of National Mammographic Screening programmes in several of these countries. Moreover, as suggested by

Robles and Galanis et al, we probably need to focus on earlier diagnosis and improvements in therapy (rather than mammography) if we are to achieve the desired reduction in mortality (11).

The increasing incidence of breast cancer may be related to decreased fertility, earlier menarche, later menopause, decreased breast feeding, increasing obesity, alcohol consumption and hormonal use. In Trinidad and Tobago, the fertility rate decreased steadily from 3.5 in 1970 to 2.4 in

1990 and 1.6 in 2004 (3). We have also recorded increasing obesity and all the aforementioned factors appear applicable to our population (19).

While each of these is important, we can expect relatively limited success in reversing these trends as they are mostly associated with evolution of the society.

Diagnostic Challenges

Only about 20% of breast biopsies in Trinidad and Tobago show cancer. The commonest lesion on biopsy is fibroadenoma and the second is fibrocystic breast disease (FBD) (8,

20). Although, this study analysed biopsies, the commonest problem presenting to the practitioners is FBD. A major diagnostic challenge is to identify breast cancer early in patients with FBD. These women have lumpy breasts and because of mastalgia (limiting compression) and younger age group mammography is often unreliable. Ultrasound then becomes quite valuable in assessing an area of particular concern. If a suspicious area is encountered, an image guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or biopsy would be the best option in such a case. Unfortunately, in T&T many benign lesions have been found to have classical clinical features of cancer. Some of these are granular cell myoblastoma (21), infarcted fibroadenoma (22), post menopausal breast abscess (23),

5

tuberculosis (24), and traumatic fat necrosis. In addition, idiopathic granulomatous mastitis may present with breast masses, ulceration, peau d’orange and lymphadenopathy and has frequently been misdiagnosed as cancer (25).

For these reasons, it is essential that a cytological or histological diagnosis is firmly established before definitive therapy for breast cancer is undertaken.

In view of the increasing mortality from breast cancer in Trinidad and Tobago and the high percentage of young victims, more effort should be directed to combating this disease. As discussed in the paper, we have to address many areas such as earlier detection of suspicious lesions, prompt diagnosis, adequate pathology services, early surgery, and adjunctive therapy if we are to succeed in our fight against breast cancer in

Trinidad and Tobago.

6

REFERENCES

1.

Ferlay, J, F Bray, P Pisani, and DM Parkin. "GLOBOCAN 2002: Cancer

Incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide." (IARC Cancer base) 5, no. 2

(2004).

2.

Parkin, DM, FI Bray, and SS Devessa. "Cancer burden in the year 2000 . The global picture." European Journal of Cancer 2001, 37, S4-66.

3.

Naraynsingh V, Hariharan S, Dan D, Bhola S, Bhola S, Nangee . Trends of Breast

Cancer Mortality in Trinidad and Tobago – A 35 year study. Cancer

Epidemiology 2010 Feb;34(1):20-3. Epub 2009 Dec 6.

4.

Althuis, MD, JM Dozier, WF Anderson, SS Devesa, and LA Brinton. "Global

Trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality 1973 - 1997." Int J Epidemiol 34

(2005): 405-12.

5.

Hennis, AJ, IR Hambleton, Sy Wu, MC Leske, and B Nemesure. "Barbados

National Cancer Study Group. Breast Canccer incidence and mortality in the

Caribbean population: comparisons with African Americans." Int J cancer, No.

124 (2009): 429-433.

6.

Phillips, AA, JS Jacobson, C Magai, N Consedine, NC Horowicz-Mehler, and AI

Neugut. "Cancer Incidence and mortality in the Caribbean." Cancer Invest 25

(2007): 476-483.

7.

Quamina, Elizabeth. Cancer in Trinidad and Tobago 2000-2002. CAREC, 2000.

8.

Raju G C, Naraynsingh V.

Breast Cancer in West Indian Women in Trinidad .

Trop. Geogr. Med. 1989 Jul; 41(3):257-60.

9.

Olsen, Gotzche. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane

Database Syst. Rev. 2001; 4: CD 001877

10.

Randall J. After 40 years mammography remains as much emotion as Science. J.

National Cancer Inst. 2000; 92 (20): 1630-1632.

11.

Robles SC, Galanis E. Breast Cancer in latin America and the Caribbean. Pan

American Health Organization, Washington. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2002;

11:178-185.

12.

Dindyal S, Ramdass MJ, Naraynsingh V.

Early onset breast cancer in black

British women (letter). Brit. J Cancer 2008. Apr. 22: 98(8):1482.

7

13.

Bradley, CJ, CW Given, and C Roberts. "Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancertreatment and survival." J Natl Cancer Institute, No. 94 (2002): 490-6.

14.

Li, CI, KE Malone, and JR Daling. "Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment and survival by race andethnicit." Arch Intern Med, no. 163 (2003): 49-56.

15.

Mouchawar J, Taplin S, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Geiger AM, Weinmann S,

Gilbert J, Manos MM, Ulcickas Yood M. Late-stage breast cancer among women with recent negative screening mammography: do clinical encounters offer opportunity for earlier detection?

J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;(35):39-46.

16.

Garne JP, Aspergen K, Balldin G, Ranstam J. Increasing incidence of and declining mortality from breast carcinoma. Trends in Malmo, Sweden 1961-1992.

Cancer 1997; 79 : 69 -74

17.

Tarone RE, Chu KC, Gaudette LA. Birth cohort and calendar period trends in breast cancer mortality in the United States and Canada. J Natl Cancer Institute

1997; 89: 251- 256

18.

Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The Changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast cancer Res 2004: 6: 229 -39

19.

Fraser HS. Obesity: diagnosis and prescription for action in the English speaking

Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publ 2003; 13: 336- 40.

20.

Raju G.C., Jankey N., Naraynsingh V . Breast disease in young West Indian women: an anaylsis of 1051 consecutive cases. Postgraduate Medical Journal

1985; 61 (721): 977-8

21.

Naraynsingh V., Raju G.U. Jankey N., Sieunarine K. Granular Cell Myoblastoma of the breast. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh 1985; 30.

91-92.

22.

Raju G.C., Naraynsingh V. Infarction of fibraodenoma of the breast. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh 1985 Jun; 30(3): 162-3.

23.

Raju G.C., Naraynsingh V.

, Jankey N. Post-menopausal breast abscess.

Postgraduate Medical Journal 1986 Nov; 62(733): 1017-8.

24.

Raju G.C., Naraynsingh V.

, Thomas F. Mammary tuberculosis presenting as carcinoma. Caribbean Medical Journal 1986 Vol. 47

8

25.

Naraynsingh V, Hariharan S, Dan D, Harnarayan P, Teelucksingh S. Conservative management for idiopathic granulomatous mastitis presenting with skin changes mimicking carcinoma - case reports and review of literature Breast Dis. 2010 Nov

23. [Epub ahead of print]

9

LEGENDS

Figure 1: Note the increasing breast cancer mortality in T & T 1970, 1985 & 2004 compared to world figures

GEOGRAPHICAL VARIATION

04

T&T

85

10

30

25

20

5

0

15

10

Figure 2 : Breast Cancer Mortality increased from about 10 to 25 per 100,000 women from 1970 -

2004

Breast Cancer Mortality Rate Per 100000 Women 1970-2004

Years

11