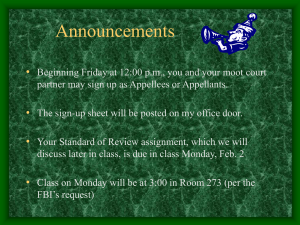

New Jersey Standards for Appellate Review

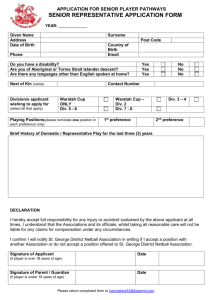

advertisement