RD300 Nimby GSX Wast..

advertisement

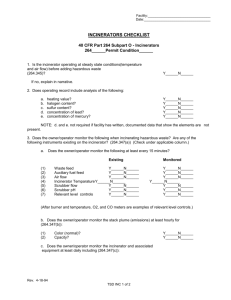

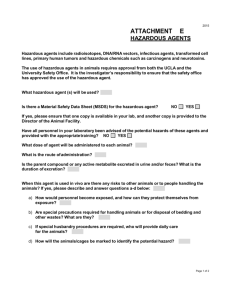

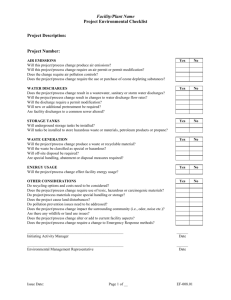

The GSX Waste Treatment Facility Case Study Source: Kaufman, S. and J. Smith (1997). The GSX Waste Treatment Facility Case Study. Journal of Planning Education & Research, 16(3): 188-200. North Broadway, long home to Cleveland industry and its workers, has changed over the years as industrial facilities in the neighborhood closed or relocated. However, its socioeconomic makeup remained relatively stable during the period when the hazardous waste treatment facility was in operation. As of 1990, the neighborhood was still predominantly white (92%), although no longer the Polish enclave it had been in the past. Both median income ($17,951) and housing values ($33,000) were well below the citywide median. Most of the housing stock was built between the turn of the century and World War II, so the resulting land use pattern was a mixture of heavy industry and residential. Alchem-Tron was one of several land uses in the neighborhood that residents might have labeled "unwanted," including an asphalt plant next door and a medical waste treatment facility down the street, as well as a nearby steel plant and a large public housing development. Alchem-Tron In 1981, Alchem-Tron, Inc. was permitted to "store hazardous wastes in tanks and containers, to distill and blend hazardous waste solvents in tanks, and to fix and solidify hazardous wastes" (Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, 1990) using open air drying beds. The State of Ohio granted the operating permit without a public hearing, which might be why residents were not initially aware or concerned about Alchem-Tron transporting and treating hazardous waste in their neighborhood. From the outset, Alchem-Tron’s relationship with state and local officials was problematic. The owner was cited repeatedly for lax handling of materials and less-than-full attention to regulations of hazardous waste treatment and storage. Alchem-Tron management responded reluctantly to violations, and usually only after the City of Cleveland or the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA) undertook some form of legal action. The facility underwent changes as new technology was introduced to increase capacity and to meet increasing regulatory requirements. Following a consent agreement with the City’s Division of Air Pollution Control at the end of 1983, Alchem-Tron proposed building a structure to cover its waste drying area and installing new technology in order to reduce airborne emissions. The City approved the plan. In 1986 Alchem-Tron installed a new thermal drying bed unit which was later classified an incinerator under EPA guidelines. City officials, aware the unit might be an incinerator, had no formal reason to take any action despite the zoning code violations because the owner had not yet requested an occupancy permit for the new building constructed to contain the incinerator (Board of Zoning Appeals, 1989). Later that year, the unit test-burned 100 tons of waste and was approved by the Chicago regional office of the US Environmental Protection Agency. In 1987, Alchem-Tron submitted its permit renewal application to the Ohio Hazardous Waste Facility Board (OHWFB). Upon notification that the inclusion of new technology and other changes in its processing capacity warranted a modification to the operating permit, Alchem-Tron had to submit a new permit application. Soon thereafter the USEPA issued a hazardous waste permit, contingent on final State approval, even while the OEPA had referred the company to the State Attorney General to press charges for additional violations. GSX Chemical Services of Ohio Alchem-Tron became weaker with each new regulatory challenge. It gradually lost clients and revenue during mandated shut-downs while trying to pay for investment in new technology that could not be used. In February 1988, the owner sold Alchem-Tron, for an estimated $15 to $25 million, to Canadian-based Laidlaw, Inc., which was then the second largest hazardous waste processing company in North America. The property, renamed GSX Chemical Services of Ohio Inc., came under the responsibility of Laidlaw’s American subsidiary headquartered in South Carolina -- GSX Chemical Services, Inc. -- which operated several hazardous waste treatment plants in the US. Laidlaw considered its investment good because it allowed quick expansion of its processing capacity in Ohio and the Midwest, and because the site was already permitted for treatment of hazardous waste including cyanide, which 1 had limited landfill options at the time. Moreover, the new thermal drying beds would increase processing capacity for hazardous solid waste materials. GSX used a compensatory strategy when bringing a LULU to a new site. It usually established a link to the host community and offered incentives for residents to accept the objectionable waste treatment activities. In Cleveland, however, GSX did not implement its usual strategy, possibly because the facility was already there and lacked a history of confrontation with the neighborhood. So the first community-company contact did not occur until after the required public notification of GSX’s intention to renew its permit. Aware that the permitting process could be delayed by Alchem-Tron's past pattern of carelessness, the GSX corporation brought in new management to improve lab and waste handling procedures. By November 1988, the operating permit appeared secure following a sparsely attended public hearing. However, in December a neighborhood resident read a public notice about the proposed incinerator and began a chain reaction to these plans. After obtaining a copy of the permit application from GSX, several residents organized and got the OEPA to postpone a decision on the incinerator until an additional public hearing could be held. Meanwhile, this loosely formed neighborhood organization got more people involved and began to engage in protest activities. They also investigated the history of the facility and of GSX, which had several law suits pending against its facilities in South Carolina, and worked to draw in their city council member, as well as others in the community. One year after the GSX purchase, opposition to it had expanded to the suburbs. A Shaker Heights resident circulated copies of a local Sierra Club member’s letter to the editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, which described how airborne by-products from the GSX incinerator would likely be wind-blown toward the Eastern suburbs. Within days, a group of Shaker Heights residents created Families Interested in a Toxic-free Environment (FITE) to stop the incinerator. FITE eventually formed a loose coalition with the North Broadway neighborhood organization and worked to bring into the dispute Cleveland’s mayor, who was campaigning to become Ohio’s governor. The Mayor came out against the incinerator after members of FITE and the North Broadway neighborhood presented ample data casting doubt on the safety of the technology and the reputation of GSX. The eloquent presentation of this evidence convinced members of the mayor’s office that opposing the company’s plans was in his best political interest. In April 1989, the OEPA and OHWFB each held a meeting in Cleveland to hear from the community and GSX before setting a new public hearing date. Hundreds of people came to speak against the incinerator, including several state and local politicians who had previously shown no interest in Alchem-Tron or GSX. A couple of these had even provided letters of support for the proposed thermal drying unit when GSX had applied for permit renewal. GSX management and lawyers took a defensive stance in their response to questions from the audience. At the second meeting with an equally large turnout, a company spokesman stated GSX would only respond to questions submitted in writing after the meeting. Within days of the Cleveland meetings, the OEPA found numerous violations during a surprise site visit and fined GSX $900,000 (later reduced to $90,000). Around this time the City of Cleveland officially entered the dispute following a citizens complaint about GSX to the Division of Building and Housing. After a site inspection, the City filed a notice against GSX, citing the company for using new buildings without a certificate of occupancy and operating an incinerator in a district which did not allow this use. A hearing before the Board of Zoning Appeals was scheduled for later in the summer. Meanwhile, the Regional Planning Commission of Cuyahoga County, responsible for transportation-related emergencies, had been asked to evaluate risks and benefits of expanding the current waste treatment operation. Planning staff prepared a set of alternative actions the Commission could take, ranging from no action to actively seeking closure of the facility. As events unfolded that spring, the Commission decided to pull out of the permit review process and defer to the OEPA and the City of Cleveland, because it anticipated time-consuming and expensive litigation. In July, 1989, Ohio's Attorney General obtained a restraining order to close GSX after an unlabeled container of hazardous chemical waste burst into flames causing injury to several employees. GSX was charged with improperly 2 storing and inadequately documenting hazardous waste at the facility, much of which had been there since it had been Alchem-Tron. In August, 1989, the Board of Zoning Appeals upheld the code violations charged by the City. In defense, GSX claimed the thermal drying beds had been included in plans approved by the City in 1984, and that the equipment technically was not an incinerator since it treated the vapor by-product of waste drying to control air pollution, without burning solid hazardous waste. Further, GSX claimed that the City had targeted its facility while other operating incinerators at several Cleveland facilities less efficient than GSX deserved scrutiny. Meanwhile, Cleveland's Division of Building and Housing granted a certificate of occupancy for the building containing the incinerator, and GSX continued to accept hazardous waste for treatment. Complaints and legal proceedings against GSX continued as the City of Cleveland and the OEPA pursued more accidents and violations. Finally, in July, 1990, the OEPA director revoked GSX's operating permit, ordering the company to stop receiving hazardous waste and to safely shut down within 90 days. GSX, allowed to continue accepting waste pending an appeal, had another accident and was ordered to shut down completely until a court decision could be made. During this respite, GSX representatives approached the neighborhood, proposing to shut down the cyanide treatment and fuel blending operations, to set up an environmental compliance committee with representatives from the neighborhood and from City and State government, and to delay incinerator operations by two years. The neighborhood group rejected all proposals. Negotiations with the City continued into the fall, and the court ordered GSX to remain closed until the November permit hearing. On October 23, 1990, GSX officials announced Laidlaw’s decision to close the facility permanently. GSX submitted a closure plan, which was approved in 1992. To date, the facility has not yet completely shut down. It continues to operate as an interim holding station for waste to be shipped to other locations for treatment. Outcome Discussion The GSX case illustrates the complex decision making process surrounding an attempt to implement unwanted change to an existing unwanted land use. All affected interests were not represented in the decision process. While the space of options was reduced from the outset, the parties' interim choices further narrowed down the options considered at each decision point. As a result, the outcome depended largely on the path created in time by the stakeholders’ choices. Following is an analysis of how each of the parties involved was affected by this pathdependent outcome and its consequences, and of how some key interests remained un-represented in the conflict. GSX GSX headquarters lost a very promising investment. The purchase represented an opportunity to expand company operations into the Midwest region of the country and the possibility of capturing a larger share of hazardous waste treatment business from outside Ohio. GSX's ideal outcome would have been to operate at full capacity including the eventual use of the incinerator. Towards the end of the process, the company offered concessions that would have eliminated the much objected-to cyanide treatment and postponed operating the incinerator. However, it was unwilling to operate without incineration capacity, because this option was financially less viable in the long run. This alternative was also temporarily eliminated from consideration when the OEPA decided to revoke the facility’s operating permit. Although the company’s appeal might have restored the permit, it required a commitment of additional funds and time for litigation while the treatment plant remained inoperable. The decision to pull out of the legal proceedings surprised the community groups who viewed GSX as the stronger opponent. However, the company’s decision was a response to the economic reality of sustaining a protracted fight with local and state regulatory agencies, politicians, and community activists in an already soft market. The Community The outcome had a mix of positive and negative effects for the immediate neighborhood of the GSX facility and for the wider Cleveland community. Preventing a hazardous waste incinerator from operating in their midst was considered positive, as was the stoppage of any treatment at the site. The residents of North Broadway gained a 3 marginally cleaner environment since other pollutant-emitting facilities in the area continued to operate. On the negative side, several residents in the neighborhood and others employed at the facility lost between 25 and 50 jobs. The neighborhood group did not go into this process with the intent to shut down the facility. However, the hostile interactions with the old and new plant management, made the plant closing an attractive prospect over time since it appeared to be the only way to stop GSX from getting its permit to operate the incinerator. Perhaps in contrast, many members of FITE did not want toxic waste to be treated anywhere in the region so they actively pursued this outcome. Although the group had nothing to gain or lose directly from a complete shutdown, FITE was satisfied with GSX’s decision not to appeal the OEPA decisions, which eliminated any chance to reinstate its permit to treat hazardous waste at the site. FITE was especially gratified with its ability to change the course of events by presenting a strong and informed argument about the potential for environmental harm posed by the facility. Public Officials Prior to public involvement in the dispute, government agencies did not appear to pursue actively the public’s protection in its dealings with Alchem-Tron. Neither the intricacy of legal procedures, nor the shortage of agency staff account completely for t he willingness of both the City of Cleveland and the OEPA to allow the company to continue operations despite repeated violations of health and safety codes. Yet the City of Cleveland and the OEPA both reacted similarly to the closure of GSX -- quick to claim victory for the community and the people of Ohio, and pleased to put an end to a potentially long litigation process. In comparison, planners who had analyzed the impact of the closure on the county for the Regional Planning Commission considered the outcome to be less than satisfactory because the negative consequences on the regional economy were not taken into consideration by anyone. Un-represented Interests As the dispute unfolded, several parties and their interests went un-represented by those affecting the direction of the decision process and its outcome. Parties actively involved in the dispute ignored some important immediate and long-term consequences of closing the facility. What impact would a closed hazardous waste facility have on economic development in the neighborhood, the city and the region? How would future efforts to introduce hazardous waste treatment be shaped by the dispute and its outcome? At no time during the dispute did GSX’s opponents seem to have considered the consequences of their actions on the future of the community, the region, or hazardous waste treatment. Similarly, any concern of GSX for the future of the site and waste treatment in Cleveland was limited to its own financial liability. While some parties involved in the conflict were aware that a complete shutdown of GSX could have long-term effects, neither the needs of GSX customers, nor the future economic development and sustainability needs of region were given any consideration. GSX customers in the Cleveland area lost a cost-effective, convenient means of disposing of their hazardous waste locally. In the long run, their loss is expected to have regional impacts as waste is shipped over greater distances for treatment, increasing the cost and risk of accidents, and the number of people exposed to accidental spills. Similarly, future needs of the region were given only partial consideration in the dispute. The Regional Planning Commission expressed some concerns regarding hazardous waste treatment needs, and community activists and environmental groups raised health and safety issues within the region. However, the opportunity to discuss long-term solutions to waste treatment and viable alternatives to the incinerator was missed by all. The decision to close the facility was independent of future site reuse. Nonetheless, the consequences of closure should have been afforded the same level of consideration as were the consequences of allowing the facility to remain open and/or to operate the incinerator. Of particular concern is the impact of closing GSX on community redevelopment. The site cannot be used or sold without an environmental evaluation. If it is found contaminated, which is likely given the history of poor handling of hazardous materials, liability and cleanup costs can make it costefficient for GSX to leave the site vacant. The site thus joins a growing list of permanently contaminated urban properties referred to as "brownfields." The high cost and risk of bringing such sites up to current environmental 4 standards often blocks redevelopment because neither current owners, nor prospective investors or the city can afford the cleanup. Un-represented in the dispute were also the concerns of other business owners wishing to operate hazardous waste treatment facilities in the area (with or without incineration). Although opponents of such operations may not see this as a concern, this remains a legitimate activity as long as such facilities are sanctioned and legal. This effect of the GSX conflict surfaced very soon after the company’s decision to close was announced. The City of Cleveland joined the North Broadway neighborhood in an effort to stop the owner of a medical waste incinerator within a block of GSX from getting an operating permit from the OEPA. The treatment facility appeared to follow Alchem-Tron’s approach by keeping its intentions quiet until the public hearing, which was held a month after the decision to close GSX. The history of violations at this facility combined with community opposition convinced the OEPA and the OHWFB to not grant an operating permit for the medical waste incinerator. However, following several appeals, claiming unfair treatment due to the GSX conflict, the facility was granted a temporary operating permit. 5