Using One Strategy - The Appreciative Inquiry Commons

advertisement

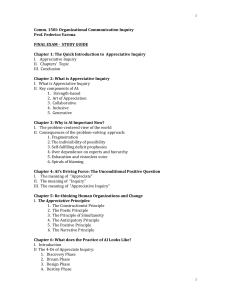

Sara L. Orem Student, The Fielding Graduate Institute For OD Network Student Competition 2002 Sleeping with the Enemy: Using Rational/Objective Methods to Enhance Appreciative/Constructivist Process Making the world a better place: All humans want a better world. Our brains and hearts allow us to envision and act for the good of that world. As our global population reaches beyond 6 billion, perhaps there are as many versions of “better world” as there are people. All would likely include as criteria adequate food and shelter, safety from harm, access to the tools for personal betterment, and a community in which to grow, share and communicate. In the more developed countries such as our own, some have these ingredients but not all. As a world citizen who works in and studies organization development, my contribution to a better world includes developing and using more universally available tools for fulfilling basic and more advanced individual and community needs. Two such tools have been refined over the last fifty years. David Cooperrider and others within Case Western Reserve’s Department of Organizational Behavior defined the newer perspective, Appreciative Inquiry, as a response to the pervasive rational problem-solving orientation of organization development. 2 Sleeping with the Enemy Cooperrider and Srivastva first published their theory and application of this perspective in Research in Organizational Change and Development in 1987. Obviously, solving problems is useful and necessary, yet, overused, it limits perspective and initiative. Appreciative Inquiry’s way is expansive, exploratory, and unconditionally positive. It has been used to explore and design participatory change in communities, government and non-government organizations, and corporations the world over. The other methodology, Transformational Learning, was popularized by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline (1990). It was theorized and practiced by Mezirow, Argyris, Schein, Schon, and others since the early 50’s. Chris Argyris defines learning as effective action, when we detect and correct error. We know what we know, he says, when we can produce what we claim we know (1994, p. 3). He characterizes incremental learning as single-loop where the learner corrects mismatches between intentions and outcomes within an existing framework (worldview) by changing an action. Transformational learning, on the other hand, is double-loop. In double-loop learning the learner reflects on her actions, seeks feedback, causing a change in her worldview and actions. Some adherents to transformational theory would characterize it as rational and objective, where the learner is an objective observer of her own actions. Adherents to Appreciative Inquiry describe it as a social constructionist perspective, one where relationship and exploration play a primary role over 3 Sleeping with the Enemy objectivity and problem solving. Yet, I will make the case that used together, they can provide more powerful learning and change opportunities than either perspective by itself. Transformational learning is a cluster of methodologies meant to lead not just to adaptive (Senge, 1990) or “informational” learning (Kegan, 2000) where the learner adds to his knowledge about something (what we know), but to a kind of learning where the learner’s knowledge of self changes and his new understanding changes the way in which the learner learns (how we know). Four Lenses of Transformational Learning: Dirkx (1998) defined four lenses through which we might view Transformational Learning. Transformational theorists and practitioners trace the creation of transformational learning to Paulo Freire. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th Anniversary Edition, 2002), he describes emancipatory education as involving the learner as active participant in designing learning. The learner asks, “What do I want to learn? Why am I learning this? How can my learning liberate and empower me?” My dream is of a society in which saying the “word” is to become involved in the decision to transform the world. Today the majority of the people are silent. Why should they have to muffle their discussion, their dissent? When they are called upon to read, why do they read only the dominant discourse? (1990, p. 94) 4 Sleeping with the Enemy Freire’s work and words always balance the need for action and critical reflection. He said in an interview about his admiration for the works of Marx, “The words of those you admire and love cannot be eaten, taken unquestionably.” (p. 78) Jack Mezirow is the best known of the representatives of the second lens. He has written and taught the concepts of cognitive critical reflection, and critical self-reflection. He shares theoretical underpinnings with Freire; both believe that adult education should lead to empowerment. Both take a constructionist approach: knowledge is not “out there” but created from interpretation of experience. Revised meaning results in what Mezirow calls “perspective transformation;” a more inclusive, discriminating, permeable perspective (Baumgartner, 2001, p. 16). Mezirow states that transformational learning develops autonomous thinking. The process of effective change takes place in our frame of reference (structures of assumptions through which we understand our experience) (1997, p. 5). Frames of reference are composed of two components: Habits of mind and points of view. Habits of mind are broad, abstract, orienting, habitual ways of thinking, feeling and acting influenced by assumptions that constitute a set of codes articulated in a point of view. A point of view is usually more changeable and accessible to awareness and feedback (p. 5). 5 Sleeping with the Enemy A third lens emphasizes human development, mentoring and experiential learning, Laurent Daloz, an adult educator, stressed the importance of a guide, supporter, and questioner. He wrote that transformation means the yielding of old structures of meaning making to new (1986, p. 140). Others with a developmental perspective include William Torbert (1972) and Robert Kegan (1982). Argyris and Schon also derive their theories from human development and social psychology. Gregory Bateson might be the father of this perspective. He wrote that self corrective systems always conserve the status quo and that we humans self-correct against disturbance. If we can’t assimilate something without internal disturbance, our self-corrective mechanisms work to sidetrack, hide, or shut off parts of the process of perception (1972, p. 435). Argyris describes this as by-passing threat or embarrassment (1994). All of the above write eloquently of the difficulty of learning and especially of transformational learning. Finally John Dirkx represents the fourth lens. He emphasizes the importance of spiritual/integrative experience to transformational learning and cautions against the exclusive rationalist perspective in developing the ability to transform and to experience transformation. “Transformative learning […] involves very personal and imaginative ways of knowing, grounded in a more intuitive and emotional sense of our experiences” (1997, p. 80). He also speaks of this intuitive way in organizations: 6 Sleeping with the Enemy The move to a learning organization perspective involves a paradigmatic shift in how we think about work, learning at work, and the role of the organization in this learning. It requires us to let go of the technicalrational views of learning and work that have dominated workplace learning for so long and embrace a contextual and constructivist understanding of work and organizational learning (1999, p. 133). Using One Strategy While Transformational Learning is older as a pervasive organizational practice than Appreciative Inquiry (during the “90’s the word “transformational” was applied to leadership, learning, change, development, growth; in short, most things organization development practitioners created and applied), both seek to change the learner and her environment in fundamental ways. By themselves, however, they both fall short. The promises of the learning organization in which Transformational Learning was to occur and where not just the learner, but the organization in which the learner works, transforms, haven’t fully materialized. Argyris, for instance, has long written about the gap between espoused theory of action, what we think we do, and theory in use, what we actually do. Few people, he says, are aware of their own inconsistencies between the two (1994, 1997). Mezirow wrote (1998) that critical self-reflection is required to measure the gap between our intentions and actions and evaluate next actions, to self-correct. The kind of fundamental 7 Sleeping with the Enemy change necessary for individuals to see differently is either slow and painful, or traumatic and ephemeral. And, as Argyris (1994) and Schein (Coutu, 2002) have recently written about the disappointments of transformational and organizational learning, individuals have to want to learn enough to survive the likely embarrassment and threat attached to adult learning. Transformational learning does, of course, happen. People make meaning of their experiences in ways that change not only their views, but how they live their lives. Organizationally, or in communities, however, that kind of learning is less predictable. Appreciative Inquiry, as a newer methodology, may still be in the “flavor of the month”/ darling of the OD community stage of its evolution, not yet subject to critical scrutiny. Transformation theorists and educators acknowledge, however, that in order to change individual and group dynamics inhibiting change, to bypass embarrassment and threat or to deal openly with it, facilitators of change must first change the values and generic action strategies of those entering change (Argyris, 1994). I believe that Appreciative Inquiry initially bypasses the threat or embarrassment attached to adult learning and is therefore a more inviting prospect as change strategy. However, I also believe that the fears attached to transformative learning are only hidden not absent and that to integrate learning strategies into an appreciative process increases its potential effectiveness. 8 Sleeping with the Enemy I believe and can demonstrate that using a combination of the entirely positive approach to change engendered by Appreciative Inquiry with methods designed to encourage transformational learning, small worlds of organizations and communities, as well as the worlds in which I have directly experimented with these methods, will result in enhanced tools for the larger world that make it better, at least for its human inhabitants. Review of Appreciative Inquiry Let me briefly review the perspective of Appreciative Inquiry. It is not new to The Organization Development Network, or to its publications. There are currently (June, 2002) more than a half dozen workshop or seminar offerings on the website (www.odnetwork.org) with Appreciative Inquiry in the title. A search of the OD Practioner yields another dozen articles over the last three years. However, for purposes of this article, it is relevant to review the steps and core questions contained within it. Frank Barrett, a graduate student with Cooperrider and co-developer of much Appreciative Inquiry material, describes five steps (in a workshop at The Fielding Graduate Institute, January 2001) in an Appreciative Inquiry process: Define, Discover, Dream, Design, and Destiny. Cooperrider uses four steps including defining a topic in the Discovery phase. 9 Sleeping with the Enemy Define: In this phase the organization seeks to choose a topic that is expansive, positive, and has the potential to engage and energize the organization, something it really cares about. Sometimes a small subgroup of the organization or community works to define the topic. Sometimes the methods of large scale intervention or future search are used to engage the entire organization or community in topic definition. Careful attention to topic perspective affects the energy to pursue the inquiry. Discovery: Uses the core questions to engage the entire organization in realizing the best of what is and the best possibilities for the future. Training enables representatives in the organization to facilitate the core questions. What gives life now? What do you most value about self and work? What do you value most about the topic/organization that you want to protect in the future? What 2-3 things would you change to make the organization even better? These generic questions are customized to reflect the topic. Dream: Focuses on the possibilities uncovered in Discovery. Data from the interviews provides the basis for understanding those characteristics of and activities in the organization that “give life” and are the foundation 10 Sleeping with the Enemy for the expansion of existing life-giving practices and the improvements people most want to see. Design: Enables the strategy for change by choosing the most effective existing practices to expand and the improvements with the greatest potential impact with an implementation strategy. Destiny: Implements the strategy and may lead to another definition and discovery cycle. Organizations use Appreciative Inquiry as a change perspective. Communities and non-governmental organizations use it to envision and build a future. Watkins and Cooperrider are careful to differentiate Appreciative Inquiry from other comprehensive change strategies. They write that Appreciative Inquiry is not a method but a way of thinking about such organization development concerns as strategic planning, Total Quality Management, diversity, and community development (2000). Why include Transformational Learning ideas in an Appreciative Inquiry Strategy: In order to be effective, Appreciative Inquiry “requires an organization to make a commitment to continuous learning, growth and generative change” (p. 4). Herein lies the rub. While Appreciative Inquiry initially generates a whoosh of positive energy, and that energy is renewed each time participants engage in the core questions, it ignores the tendency in organizations toward returning to steady state, or business as usual. It ignores the threat and embarrassment of 11 Sleeping with the Enemy learning. Most of us do not make transformative changes as long as what we learn fits neatly into our already constructed worldview. And most of us, when confronted with something new like Appreciative Inquiry, will ultimately ignore it if it is too dissimilar to our already constructed worldview. Cahill-Weber’s Executive Leadership program created for Darden Business School (1997) quotes John Kenneth Galbraith, “faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.” Personal experience indicates that at least some of any group of participants in an organizational change initiative will resist or at best comply with the requirements of the initiative. Some will come along for the ride and get enthusiastic and active along the way, and some will champion the process. While it is easier to engage in Appreciative Inquiry than any other initiative I have tried because participants tap their own passion about work and change, talking about and acting on change are two very different things. Somewhere in the engagement, real work intrudes and it is relatively easy to justify giving up on the “extra work,” even when it is as engaging as Appreciative Inquiry. If, as Argyris writes, all learned human action is designed (1997), then an explicit design acknowledging the challenges of transformational learning in Appreciative Inquiry will at least put the assumptions on the table. Appreciative Inquiry shortcircuits recreational complaining (by circumventing discussion of the problems in 12 Sleeping with the Enemy an organization) and may therefore appeal to both sponsors and facilitators as a better way. But finger pointing may only be under the surface and silent, not absent. Ways in which I invite incremental and transformational learning into an Appreciative Inquiry process are: Have the usual kick-off or rally where the CEO or sponsor describes why she is introducing Appreciative Inquiry. Give attendees a taste of answering the core questions. Make clear that participation is voluntary, because significant change is not for the feint of heart. Invite people including executives into the process, but don’t require them to participate. This is easier when internal facilitators will design and manage the process and harder when the organization has spent a hefty amount of money contracting a change strategy. It does assure that the people who participate want to have the opportunity to learn. Keep track of the number of participants. If the number doesn’t increase in a few months due to word of mouth and organizational communication, review the real support for change. If no increase, find another way. Let champions of the process spread the word through their networks, not executives as an edict. Build participation through attraction not coercion or even subtle political force. This is basic to Freire’s emancipatory learning. Support the process with organization-wide communication about how the initiative is going, times of meetings, invitations. 13 Sleeping with the Enemy Support learning groups and provide journals and opportunities for critical self-reflection about individual learning in the process. This supports the ability to increase critical self-reflection and make better individual and organizational decisions. A short Appreciative Inquiry case study: New leadership of a midwestern bank wanted to increase the engagement of its workforce through a positive approach to change. They purchased a reputable leadership seminar and trained with the creators so that company executives deliver in-house. An appreciative process picks up graduates six weeks after the initial three-day program. Prior to this addition, there was no formal structure for participants to continue changes they initiated in the seminar. Executives agreed that Appreciative Inquiry was the best way to keep the dreams of the participants alive and to spread the dreaming (and resulting actions) throughout the organization. Definition: The topic choice was continuing to dream the future. Discovery: In groups of thirty, participants learned the basic Appreciative Inquiry framework and interviewed each other using the core questions. The COO made clear that he wants to see dreams that teams can implement in their own area. He discouraged ideas about what he and the CEO should change. Each participant left with a journal to record her own reflections about the process and a script for enlisting her own teams in an appreciative process. 14 Sleeping with the Enemy Dream: Ninety days after the initial learning session, groups reconvened to share their experience of the discovery phase and to marry the dreams expressed by their teams with the mission of the bank. Some of the participants had not yet met with their teams for the discovery phase. Some teams had moved to design the improvements for their teams and with other teams. The facilitator introduced learning groups and reviewed journaling, now for critical self-reflection. There was time for participants to gather in an initial learning group at the end of the session. Design: Corporate communications kept the organization informed about the designs generated in teams and the successes of teams that had begun to implement. Active teams were featured and the invitation to participate was extended. More teams ended participation. Some individuals joined other more active teams. Destiny: Participating teams began to implement their designs. It is too early to tell what the organization-wide results will be. Conclusion Appreciative Inquiry generates an unusually enthusiastic response to beginning a change initiative. A good thing and the bad thing about corporations and organizations that pay salaries is that there is some inherent pressure to comply with initiatives, to stick around long enough for possible engagement. In communities and some other places where Appreciative Inquiry has been initiated, participation is more obviously voluntary. However, unless resistance to learning, certainly to transformation, is addressed in a direct way, the initiative 15 Sleeping with the Enemy has less chance of enabling change. Unless someone offers the tools and support for enabling transformation, few will manage it on their own. Then the force of the change may dissipate as soon as the sponsor’s attention diverts elsewhere. The combination of enabling stronger relationships by dreaming a future together, a social construction, with a rational, individual learning opportunity may succeed where one or the other fails more of the time. Troubles in Palestine loom. Good people are unable to join across a widening divide. They are each (all) entrenched in their own worldview. If an appreciating approach engaged us and them and transformation enabled new views, all world citizens could more clearly see organization development’s contribution to their betterment. Presentation: Session Purpose: To engage participants in an Appreciative Inquiry process with overt transformational learning tools so that the participant will experience core questions in a group setting, use self reflection as a way to enhance ability to facilitate parts of Appreciative Inquiry and define future learning needs for use of the combined perspectives. 5 minutes: Introduction of self and session purpose: Ask participants to describe their prior experience with Appreciative Inquiry and Transformational Learning. 16 Sleeping with the Enemy 20 minutes: Brief Review of Appreciative Inquiry Model and Core Questions 15 minutes: Group customizes Core Questions 17 Sleeping with the Enemy for small group activity. Participants experience creating the questions based on their interest and energy. 30 minutes: Pairs interview each other using the Core Questions. Each participant has the direct experience of positive self and organization talk. 20 minutes: Debrief interviews in large group. 5 minutes: Four lenses of Transformational Learning 10 minutes: Pass out journal pages with self reflection questions. Participants answer questions individually, then share any responses to exercise. 18 Sleeping with the Enemy 15 minutes: Break. Pass out evaluation for thinking and chatting at Break. How will you evaluate yourself in this session at the end of it? 10 minutes: Debrief evaluation request. 40 minutes: Using the four lenses, participants design next part of session. Arrange own teams for discovery. Sample questions: How many teams? Who facilitates? What do you want to discover together? What do you want to learn about self, process, others? What do you want from facilitator? 10 minutes: Second journal sheet with questions for self reflection Questions about self participation, internal resistance. 40 minutes: Deliver on participant design 20 minutes: Final comments and self evaluations. 19 Sleeping with the Enemy References: Argyris, C. (1994). Knowledge for Action: A Guide to Overcoming Barriers to Organizational Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Argyris, C. (1997). Learning and Teaching: A Theory of Action Perspective. Journal of Management Education. Vol. 21, No. 1, 9-26. Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc. Baumgartner, L. (2001). An Update on Transformational Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. No. 89, Spring. Cahill-Weber Group. (1997). Creating the Future: The Leadership Challenge. An executive development program designed for The Darden Graduate School of Business at the University of Virginia. Coutu, D. (2002). Edgar H. Schein: The Anxiety of Learning. Harvard Business Review. Vol. 80, No. 3., 100-106. Cox, M. (1990). Interview with Paulo Freire. Omni. New York: April, Vol. 12, No. 7, 74-94 Cooperrider, D., Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life. In Pasmore, W., Woodman, R. (Eds.) Research in Organizational Change and Development, Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Daloz, L. (1986). Effective Teaching and Mentoring. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Dirkx, J. (1997). Nurturing Soul in Adult Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. No. 74, Summer. 20 Sleeping with the Enemy Dirkx, J. (1999). Invited Reaction: Managers as facilitators of learning in learning organizations. Human Resource Development Quarterly. Summer. Freire, P. (2002). Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. New York: Continuum. Kegan, R. (1982). The Evolving Self. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kegan, R. (2000). What ‘Form’ Transforms?: A ConstructiveDevelopmental Perspective on Transformational Learning. In J. Mezirow and Associates (Eds.), Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Mezirow, J. (1996). Contemporary Paradigms of Learning. Adult Education Quarterly. Vol. 46, No. 3, 158-172. Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. No. 74, Summer. Mezirow, J. (1998). On critical reflection. Adult Education Quarterly. Vol. 48, No. 3, 185-195. Senge, P. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization. New York: Currency Doubleday. Torbert. W. (1972). Learning from Experience: Toward Consciousness. New York: Columbia University Press. Watkins, J., Cooperrider, D. (2000). Appreciative Inquiry: A Transformative Paradigm. OD Practitioner, Vol. 32, No. 1.