ICTs and the engineering of encounters

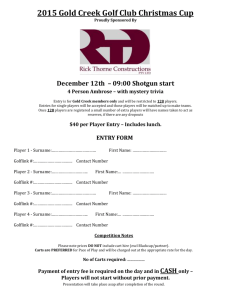

advertisement