Male Retention at the Community College

advertisement

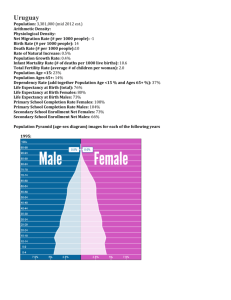

Male Retention at the Community College Andrew J. Manno Raritan Valley Community College amanno@raritanval.edu Male Retention at the Community College 1 Introduction Across the country at both two- and four-year colleges, by almost every measure available, males are underperforming both in relation to previous indicators of male success and in relation to female success. They are entering college at lower numbers than in the past, earning lower grades, dropping out more frequently, transferring less successfully, and graduating at lower rates. At the same time, females are making remarkable academic progress, outpacing men in all of these categories, making up the majority of graduates in many disciplines, earning more doctorates overall than men, and quickly catching up to men in graduating with degrees in disciplines that have traditionally been male dominated. There is a danger in assuming that increased opportunities for females translate into disadvantages for males. However, while we should celebrate female successes, we should be quite concerned about male declines. The findings that will be presented suggest an increasing male educational disengagement that has potentially serious social implications. The purpose of this paper is to bring together some of the major national findings about male collegiate success, data from selected New Jersey community colleges on male retention, research suggesting decreased male social engagement, and studies of gendered approaches to career counseling in order provide the context for suggestions that I will make for concrete actions at the community college to address these concerns. Part I: Male Retention Nationally According to data from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES), between 1970 and 1996, the share of male bachelor’s degrees awarded in traditionally Male Retention at the Community College 2 male fields decreased substantially while the female share has increased. In business, the share of male degrees increased by 21%, while the shares of female degrees increased by 994% and the proportion of bachelor’s degrees awarded to males shrank from 91.3% to 51.4%. In agriculture, the male share increased by 12% in comparison to the female share increase of 1273%, and the proportion of bachelor’s degrees awarded to males shrank from 95.8% to 63.2%. In architecture, there was a 37% male increase as compared to a 1288% female increase, and the proportion of bachelor’s degrees awarded to males shrank from 94.7% to 63.9%. In fields traditionally dominated by women, however, such as education, visual/performing arts, English, and foreign languages and literature, there has been a negligible gender shift (Opportunity no. 76). Overall, males earned only 44.4% of the bachelor’s degrees awarded in 1997 (Opportunity no. 102). NCES projects that if male declines continue at the current rate, by 2008, females will earn 58% of all bachelor’s degrees compared to a 42% male portion (Opportunity 83). Many colleges and universities are taking these trends quite seriously, and have begun efforts at addressing this growing male educational disengagement. At Dickinson College in 2000, for example, the male percentage of the freshman class grew to 43% male from 36% partially as a result of preferences the college gave to “qualified male candidates at the margin” (Fonda). The Maryland alumni chapter of the AfricanAmerican fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, furthermore, has created a mentoring program for high school males intended, according to the program head David Barnett, at “helping boost their grades and inspiring them to apply to college” (qtd. in Fonda). Barnett adds, “So many of our boys are in prison. The ones in school—they’re under tremendous pressure from their peers not to excel academically” (qtd. in Fonda). Noted masculinity Male Retention at the Community College 3 studies scholar Michael Kimmel supports this notion, indicating that “once we begin to change the anti-intellectual current in our culture, market forces will help address the gender gap” (qtd. in Fonda). Pierce College in Puyallup, WA has attempted to address some of the pressures that men face as college students by creating a Men’s Program, one of only a handful in the country. Created in an effort to respond to data indicating that male students at seven Washington state colleges and universities fail at twice the rate of females, the Men’s Program works to “create a community of active and successful male learners through personalized support and academic guidance” and acknowledges that “many men face difficulties in continuing their education” (“Men’s Programs”). The three key components of the efforts at Pierce College are mentoring, a student support group, and a men’s issues lecture series. According to the Program’s administrators, “the cultural practices that teach boys at a very young age to close off their emotions isolate them as men in a world that expects them to fend for themselves with little interpersonal support” (“Men’s Programs”). The Men’s Program, then, recognizes that “men and boys do have difficulties and the responses can be based in part on some of the models pioneered by the women’s movement, as men’s centers with a number of supportive connections available” (“Men’s Programs”). The trend of male educational disengagement also appears in relation to graduate degrees. According to Northeast University’s Center for Labor Market Studies, among 1999-2000 Master’s degree recipients, females earned 138 degrees per 100 awarded to men (Conlin 78). Further, among those students receiving doctorates in 2002, females received 51% (up from 44% in 1992) while males received 49% (a 15% drop since 1997) Male Retention at the Community College 4 (Smallwood). This gender shift as a whole is even greater among associate degree recipients. While the proportion of bachelor’s degrees awarded to males decreased from 56.9% to 44.9% between 1970 and 1996, the proportion of associate’s degrees awarded to males declined by 17.5% from 57% to 39.5% (Opportunity no. 76) and by 18.1% from 57.1% to 39% from 1966 to 1998 (Opportunity no. 104). Part II: Male Retention at the New Jersey Community College Not surprisingly, male retention at the New Jersey community college reflects the national trends described above. Graduation rates at selected New Jersey community colleges as reported to NCES for 1999 (the most recent year for which such data has been reported) indicate that females graduated in every case at higher rates than males, and in some instances significantly higher: College Male Graduate Rate Female Graduation Rate RVCC 0.086 0.156 Bergen 0.068 0.117 Brookdale 0.145 0.215 Burlington 0.124 0.152 Mercer 0.117 0.176 Middlesex 0.044 0.123 Morris 0.164 0.264 Ocean 0.206 0.270 Male Retention at the Community College 5 A different pattern emerges, however, when examining 1999 New Jersey community college transfer rates by gender: College Male Transfer Rate Female Transfer Rate RVCC 0.253 0.267 Bergen 0.213 0.192 Brookdale 0.201 0.190 Burlington 0.094 0.148 Mercer 0.127 0.094 Middlesex 0.136 0.123 Morris 0.296 0.240 Ocean 0.206 0.270 In five of the eight New Jersey community colleges studied, then, males transfer at a higher rate than females. However, RVCC data from fall 1998 indicates (and data from 1999-2000 confirms) that, among students who transfer, males earn lower average cumulative G.P.A.s (3.02 for males and 3.27 for females) as well as earning a lower total average number of credits upon transfer (66.50 for males versus 67.53 for females), resulting in what can be characterized as a less successful transfer. Other indicators of student retention support the contention that males at the New Jersey community college are underperforming. One measure of student retention is the “Stop Out Rate,” the rate by which students leave college and don’t return for at least Male Retention at the Community College 6 three academic years. Of the 1998 RVCC cohort, male stop-outs performed more poorly than female stop-outs, earning an average cumulative G.P.A. of 0.88 versus the female’s 1.13. Additionally, of the stop-outs, males earned a lower average total number of credits (8.23 for males, 9.82 for females). Of 1998 RVCC graduates who didn’t transfer, females slightly outperformed males in average G.P.A (3.02 for males versus 3.03 for females) and earned a greater average number of credit hours (65.20 credits for females versus 68.50 credits for males). Of the RVCC 1998 cohort students who transferred without a degree, females earned a higher average cumulative G.P.A (2.47 versus the male average of 2.21) and a higher average total credits earned (31.44 versus the male average of 26.92). Again, the same patterns apply for 1999 and 2000 data. Fall 2000 RVCC success rates by gender underscore these findings: Stop-Out Graduate Grad & Tran Transfer Still Enrolled Male 33.2% 4.0% 7.2% 24.1% 19.5% Female 21.6% 6.1% 9.0% 25.5% 21.3% In summary, male New Jersey community college students represented by this data drop out, graduate, graduate and transfer, and are still enrolled at lower rates or less successfully than females. This mirrors national trends that indicate that the gender divide in higher education and the resulting male educational disengagement are even more pronounced for community college students than for students at four year colleges and universities. Male Retention at the Community College 7 Part III: Issues at the Male Elementary and Secondary Educational Levels The lives of boys and men are very different than they were a generation ago. Higher education public policy expert Thomas Mortenson in the August 1999 edition of The College Board Review argues that “delayed marriage, unwed motherhood, divorce, remarriage, working mothers, and other influences have redefined families and have affected the development of children” (12), one result of which is the “the absence of the father” and the loss of “the male model” (12-13). Boys face other problems in school before college. Adult male models are rare in the K-12 classroom, 73.4% of learning disability diagnoses are for boys, and males “dominate all disability categories” (13), including speech impairment, mental retardation, and hearing impairment (13). In high school, girls show signs of better academic preparation (with 36.8% of 1998 high school freshmen girls reporting A grades to 27.4% of boys) and use pre-college outreach services more readily (with 2/3 of the clientele female) (13). Of high school students, 73% of those with diagnosed learning disabilities and 76% of those with diagnosed emotional disturbances are males (13). James Garbarino, Professor of Human Development at Cornell University states, “Girls are better able to deliver in terms of what modern society requires of people—paying attention, abiding by rules, being verbally competent, and dealing with interpersonal relationships” (qtd. in Conlin 78). The educational gender gap is wide ranging and suggests the extent to which the educational system is not adequately serving the needs of boys. On national reading tests administered in 2000 based upon a scale of 0 to 500, female fourth graders scored an average of 222 points compared to the male average of 212 points, according to NCES data. On national math tests administered in 2000 based upon a scale of 0 to 500, Male Retention at the Community College 8 females are quickly catching up to males in subject areas in which females have not in the past done so well during high school years. Female twelfth graders scored an average of 299 points compared to the male average of 303 points (Conlin). The gender gap also appears in regards to percentage of involvement in high school extracurricular activities, with females being involved in non-sports-related clubs and activities at significantly higher rates than males: Female Male Student Government 27% 19% Music/Performing Arts 46% 35% Yearbook/Newspaper 29% 21% Academic Clubs 36% 28% Athletic Teams 49% 63% (Source: 2000 NCES data, Conlin) The implications of this data are disturbingly clear. The men represented by the data gathered from this study appear to embrace stereotypic gender roles and gravitate towards athletics and away from academics, contributing to male educational disengagement. Part IV: Male Educational and Social Disengagement: College and Beyond College aged men tend to spend their time differently than women, putting far less emphasis on academics and civic engagement and more on “playful activities” (Opportunity no. 133). According to the 2002 freshman survey from the Higher Education Institute at UCLA, while females spent more of their time participating in student clubs, doing housework or childcare, studying, or performing volunteer work, Male Retention at the Community College 9 men spent more time playing video games, watching television, partying, or playing sports. At every institutional type four-year female college freshmen spent more time per week on average studying (4.1 hours at public four-year colleges, 5.0 at public universities, and 7.7 at private universities compared to 2.8 , 3.4, and 5.4 hours respectively for men) (Opportunity 133). The number of male students spending six hours or more per week studying has decreased between 1987 and 2002 from 41.4% to 26.9% for a total of a 14.5% decline. During the same period, female student rates declined from 52.2% to 38.7% for a total of a 13.5% decline. The 2002 freshmen survey also points out that women spent an average of 1.3 hours per week performing volunteer work, but men spent only 0.6 hours per week. Freshmen women spent an average of 2.0 hours per week working on student clubs, while men spent only 0.9 hours. Further, 21.9% of women reported spending six or more hours per week “partying,” compared to 29.0% of the men surveyed, and 32% of male freshmen reported watching six or more hours of television per week compared to 21.1% of women. Men watched an average of 4.0 hours of television per week and played video games for 1.9 hours per week, while women reported 2.8 and 0 hours respectively. Not surprisingly, with less time devoted to “playful” activities, 35.2% of women compared to 16.4% of males reported feeling stressed and overwhelmed with their workloads (Opportunity 133). Other changing social forces play a part in the educational disengagement of men. According to the 1990 census, 75% of Americans live in urban areas. Mortenson argues that the communications, cooperation, and social networking abilities of women are more important to success in the newer, dense urban world Male Retention at the Community College 10 than are the physical strength and aggressive characteristics of males that were more important in a primarily rural time and place. (14) The economy, furthermore, has shifted from a goods-producing economy that includes such industries as manufacturing, mining, and construction to a “private- service producing” economy that includes such industries as retail trade, wholesale trade, finance, insurance, and real estate. The goods-producing jobs, then, favoring male advantages in physical strength and mechanical and motor skills are disappearing, and some researchers as a result are arguing that men are “disengaging from their economic roles,” (15) with rates of male participation in the work force declining since World War II. Thus, “men hold dominant employment positions in industries that represent a shrinking share of employment [and] . . . are more unemployed and generally less able to adapt to the changing nature of the new economy” (Opportunity no. 83). Men are also playing less of a civic role than they once had, with male voting rates declining 19.1% between 1964 and 1996, while female voting rates declined 11.5% during the same period (Opportunity no. 83). The result is that more women currently vote than men (Conlin 79). The social impact of male academic disengagement is great: Better educated men are. . .on average, a much happier lot. They are more likely to marry, stick by their children, and pay more in taxes. From the ages of 18 to 65, the average male college grad earns 2.5 million over his lifetime, 90% more than his high school counterpart. That’s up from 40% in 1979, the peak year for U.S. manufacturing. (Conlin 79) British educators have long since identified the perils of “laddism” (or academic male disengagement) and have worked for the past decade to combat it, but the American Male Retention at the Community College 11 educational system has not even named the phenomenon, much less raised public attention or started a sustained national effort to address it (Conlin 78). Part V: Gender and Counseling Attempts at addressing male social disengagement are beginning to get underway in the area of college level career counseling. According to several studies, men “express more negative stigma towards career counseling services than women” (Rochlen et al 127) and as a result are less likely to use traditional career counseling services. Pilot studies revealed that alternative career counseling services that take into account masculine attitudes towards traditional career counseling have been effective in increasing career counseling service use by men: Men preferred a more structured, directive approach to career counseling than a more integrative, affectively oriented career counseling process. . . . Alternative services (classes, videotapes, structured interventions). . .were perceived as more structured and less emotionally intrusive. . .and more palatable to those with high traditional masculinity. (128). In addition, researchers found that modifying labels in career counseling brochures also increased positive male response to career counseling services. For example, the word “counselor” was changed to “consultant,” “emphasizing the process of career counseling as one that involves a structured process and emphasizing that in career counseling the client makes the decisions” (130). This kind of re-positioning of traditionally provided college services to meet the emotional realities of men is a good example of the kinds of changes that need to be made at community colleges (as well as at colleges and universities) to increase male academic engagement. Male Retention at the Community College 12 Part VI: Recommendations There is a national problem with male educational disengagement. National data suggests that men are entering college at lower numbers than in the past, earning lower grades, dropping out more frequently, transferring less successfully, and graduating at lower rates. They are also underperforming in relation to females in these categories, and the decline in male educational success also appears with recipients of Master’s degrees and doctorates. Data from selected New Jersey community colleges supports this national data. Even attempts to dis-aggregate the national data to account for race and ethnicity ultimately identify a “sharp downturn in the male share of traditional-aged undergraduate enrollment among middle- and upper-income whites” (King 4). This trend towards male educational disengagement has broad implications, the most disturbing of which is an associated male social disengagement. Young men are involved far less than young women in academic activities, for example, while their college age male counterparts spend less time studying and volunteering and more time partying, watching television, and playing video games than females. Addressing this trend is incredibly complicated and far beyond the scope of this paper. In fact, a broader societal shift might need to take place to begin to deal with these issues. A large part of the problem, furthermore, is that there has not been an extended, systematic discussion of these issues. Administrators at community colleges and fouryear colleges alike should begin to address this until-now-hidden dilemma. Male social disengagement and its educational consequences should be made an important agenda item for college administrators serious about gender equity and retention. Male Retention at the Community College 13 Works Cited Conlin, Michelle. “The New Gender Gap.” Business Week. May 26, 2003. Fonda, Daren. “The Male Minority.” Time. December 02, 2000. Guerin, Keith, RVCC Director of Institutional Research. NJ Community College Success Rate data reported to NCES. January 22, 2004. King, Jacqueline. “Gender Equity in Higher Education: Are Male Students at a Disadvantage?—Updated Tables and Figures, August 2003.” American Council on Education Center for Policy Analysis. 2003. Mortenson, Thomas. “Changing Industrial Employment Effects on Men and Women 1939 to 1988.” Postsecondary Education Opportunity, no. 83, May 1999. ---. “Gender Differences in Time Use of College Freshmen 1987 to 2002.” Postsecondary Education Opportunity, no. 133, July 2003. ---. “Projecting Bachelor Degree Recipients By Gender 1980 to 2000.” Postsecondary Education Opportunity, no. 102, December 2000. ---. “Where Are the Boys? The Growing Gender Gap in Higher Education.” College Board Review, no. 188, August 1999. ---. “Where Are the Guys?” Postsecondary Education Opportunity, no. 76, October 1998. ---. Where the Guys Are Not: The Growing Gender Imbalance in College Degrees Awarded.” Postsecondary Education Opportunity, no. 83, May 1999. “Pierce College—Men’s Program.” http”//www.pierce.ctc.edu/mensprogram/index.php3. October 17, 2002. Rochlen, Aaron, Christopher Blazina, and Rajogopal Raghunaan. “Gender Role Conflict, Male Retention at the Community College 14 Attitudes Toward Career Counseling, Career Decision Making, and Perceptions of Career Counseling Advertising Brochures.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 3:2, 2002: 127-137. Smallwood, Scott. American Women Surpass Men in Earning Doctorates,” The Chronicle of Higher Education. December 12, 2003.