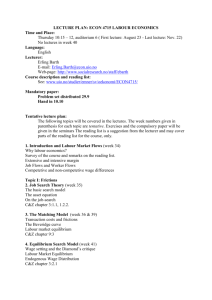

Outline Conference Paper

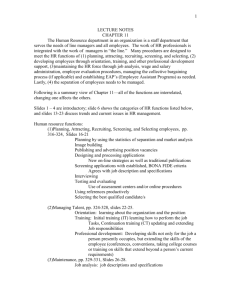

advertisement