Becoming a Grammar Teacher

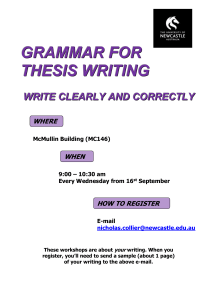

advertisement

Becoming a Grammar Teacher: Why? What? How?

By Richard Hudson

July 2012

Becoming a Grammar Teacher: Why? What? How? .................................................... 1

Executive summary........................................................................................................ 1

1 Introduction and overview ..................................................................................... 6

2 My credentials ........................................................................................................ 8

3 A brief history and geography of grammar teaching ........................................... 10

4 Why, what and how ............................................................................................. 13

5 Why? .................................................................................................................... 14

5.1

Writing ......................................................................................................... 15

5.2

Reading ........................................................................................................ 16

5.3

Speaking and listening ................................................................................. 18

5.4

Foreign languages ........................................................................................ 20

5.5

Thinking ....................................................................................................... 20

6 What? ................................................................................................................... 22

6.1

Lexical relations and morphology ............................................................... 23

6.2

Syntax .......................................................................................................... 29

7 How? .................................................................................................................... 35

8 The obstacles ........................................................................................................ 39

Executive summary

This document is an attempt to make secondary English teachers more

enthusiastic about teaching grammar. Most such teachers received little or no

formal instruction in grammar either at school or at university, which is an

obvious and serious obstacle to the re-introduction of grammar teaching. But

negative stereotypes of grammar teaching discourage some teachers from

learning about it, so before this gap can be filled, it is possible that these

teachers need to be persuaded of the benefits of teaching grammar.

Grammar ceased to be taught in our English lessons in about 1960, and

somewhat later in foreign language classes, but was reintroduced in the first

National Curriculum of 1990. Since then it has had an increasingly prominent

place in the curriculum for both English and Foreign Languages, including the

new (in 2012) draft curriculum for English.

But as currently practised, grammar teaching does not seem to be working,

because (according to two grammar audits of new undergraduates) school

leavers don’t know any more grammatical terminology now than they did in

1986.

This situation is neither natural nor inevitable, because at other times and in

other places grammar is, or has been, taught much more successfully.

Why teach grammar? The research evidence and/or common sense suggests

that it benefits five educational areas:

o writing

o reading

o speaking and listening

o foreign languages

o thinking skills

What is there to teach in grammar? In the context of grammar teaching, it is

useful to distinguish two areas:

o lexical relations and morphology

o syntax

In both cases grammar can throw light on texts, whether literary or not, but

some kinds of analysis need a notation such as the diagrams that are often used

in linguistics.

How should grammar be taught? Three general principles are offered:

o grammar should be taught systematically in a ‘spiral curriculum’,

which avoids the conflict between systematic teaching and teaching

‘when needed’.

o it should be integrated with other parts of teaching

o standard technical terminology should be used, as it is important for

different teachers, both within and across schools, to use the same

terminology.

Preface

Just after the National Curriculum was first introduced into England I was invited to

write a book about grammar teaching1. That was 1992, and twenty years later here I

am again, writing a book about grammar teaching in the National Curriculum. Why?

For one thing, the world has changed in the last twenty years. We’ve switched

governments from Tory to Labour, and then back to Tory again; and between them,

those governments have introduced three different versions of the National

Curriculum for English, and now we’re waiting for a completely new version of the

entire National Curriculum. Grammar was a significant part of the earlier versions,

but it’s likely to be an even more prominent part of the next one. As far as

Government is concerned, grammar is here to stay. But during those twenty years, a

lot has happened in our schools. The idea of having a National Curriculum has bedded

down and become widely accepted; the National Literacy Strategy has come and

gone; league-tables have come to dominate almost everything.

Other changes have affected the curriculum itself. The first English curriculum

is strong on variation, including differences between spoken and written language and

between Standard English and non-standard dialects2. But it gives very little detailed

guidance on what areas of grammar should be covered, or on what concepts and

terminology should be taught. The National Literacy Strategy introduced a lot of

grammatical guidance, including the first-ever official glossary of grammatical

terminology and a book of teaching suggestions about grammar for primary schools

called Grammar for Writing. The glossary was a remarkably poor document which

some of us linguists were allowed to revise long after it had been published;

fortunately, it seems to have been generally ignored but unfortunately, so does our

revision. In contrast, Grammar for Writing was widely welcomed and seems to have

had some effect on grammar teaching in primary schools. In contrast, there has been

very little official guidance on grammar for secondary teachers3.

One major change to secondary English teaching has been the rise and rise of

A-level English Language, which from tiny beginnings in the early 1980s has become

the 13th most popular A-level subject (and for girls, the 9th most popular)4. Thanks to

this new school subject which hardly existed in 1992, thousands of English teachers

are now teaching some grammar and presumably discovering that grammar might be

not only relevant, but also teachable and (even) fun.

A third change is that the UK is now recognised to be facing a crisis in its

foreign-language education. 1992, when my first book was published, happened to be

the year when A-level entries for foreign languages peaked, but since then the

numbers have declined dramatically, with French entries dropping from 31,000 to

13,0005. Similar falls have been registered in entries at GCSE so that fewer than half

of all pupils now take any foreign language at GCSE. Even more depressingly, these

problems only apply to state schools, so languages are in danger of becoming the

special preserve of independent schools. Almost everyone agrees that the crisis is

1

Hudson 1992

There is a list of relevant passages from the 1990 National Curriculum in Barton and Hudson

2002:263-79.

3

I was asked to produce two semi-official websites suitable for secondary teachers: ‘KS3 Grammar’

(http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/tta/KS3.htm) and ‘Grammar in the Secondary National

Strategy’ (http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/kal/top.htm).

4

http://tinyurl.com/ca2010gce

5

For these and other figures, see http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/ec/stats.htm#fl.

2

serious, to the extent that it has become an ongoing campaign issue at the British

Academy, and also that, among the many complex and deep-seated causes is the very

boring curriculum for GCSE languages. One possibly important element in this

gloomy picture is the very small role that grammar still tends to play in language

teaching. The idea of teaching a language without any mention of its grammar is a

bizarre one, with nothing to recommend it as part of education; and it is even odder if

children already know grammatical ideas and terminology when they come to the

Foreign-Language classroom, thanks to the National-Curriculum requirements for

English.

This brings us to a major contradiction in our schools. Ever since 1990, the

National Curriculum has required both primary and secondary schools to teach

grammar as part of English and Foreign Languages. But there are good reasons for

thinking that this bit of the National Curriculum has failed. Whatever teaching of

grammar may be taking place – and anecdotally one hears of a great deal of grammar

work being done in primary schools in particular – it doesn’t seem to be making much

difference. Teachers of A-level English Language, who are probably the best placed

to use any grammatical knowledge that pupils have picked up, report no increase at

all6. Similarly, a ‘grammar audit’ in 2010 of incoming undergraduates found that, if

anything, they knew less grammatical terminology than their counterparts did in a

similar audit conducted, using the same instrument, in 19867. In short, if you want

grammar to be taught, it’s not enough to say so in official documents; something else

is needed.

What is that extra something? Teachers, and especially secondary English

teachers, need to be both willing and able. The fact is that most English teachers were

taught no grammar either at school or during their undergraduate English degree8

(although the situation is very different now from 19929); and many came through

PGCE courses which actively discouraged them from teaching grammar. To say this

is not, of course, to criticise the teachers. The lack of grammar in their school and

undergraduate courses is not their fault, nor does ignorance of grammar imply lack of

ability. On the contrary, secondary English teachers are amongst the most able

teachers in our schools by any standard. Why should a teacher whose professional

expertise is based on literary and cultural studies take grammar (of all things!)

seriously, especially given the terrible press that grammar has had over the years?

This isn’t just a rhetorical question. Why should such a teacher bother to teach

grammar? Even more importantly, why should they bother to invest significant

amounts of time and pain in learning enough grammar to teach it confidently and

competently? This book is an attempt to take that question seriously, but I can already

hint at part of the answer: pupils like grammar. One rather trivial piece of evidence: if

I search the internet (in mid 2012) for the phrases “I hate grammar” and “I love

grammar”, Google finds twice as many examples with “love” than with “hate”. But a

much more significant piece is the enthusiasm among pupils for the recently

6

This is one of the recurrent themes of the major email list EngLang, which is dedicated to teachers of

English Language at A-level.

7

For the data and analysis, see http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/ec/ba-kal/ba-kal.htm. I give a

little more information about this project in section 2.

8

Cajkler and Hislam 2002, Williamson and Hardman 1995

9

But PGCE courses are much more willing nowadays than they were in 1992 to accept graduates of

either English Language or Linguistics. For some research data on requirements for English PGCE

courses, see Blake and Shortis 2010, Committee for Linguistics in Education and others 2010; an

earlier survey is discussed, with data, at http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/ec/pgce-clie.htm.

introduced Linguistics Olympiad10, which is largely about grammar. As one pupil

said, "it mashes yer 'ed, but in a good way".

10

See http://www.uklo.org.

1 Introduction and overview

This book is a plea for schools to teach grammatical analysis as a standard and

significant part of the curriculum. To give a taste of what I have in mind, let’s move

straight to the end of the story, to a school where grammatical analysis is already well

established and working smoothly. It could have been a primary school, but a

secondary school is more relevant to this book.

*****

Let’s follow a Year 8 class in this school. The first lesson is English, which

starts with a brief activity about modal verbs: What’s the difference between must and

have to, as in I must go and I have to go? The students work in pairs to spot the

differences, and after five minutes the teacher compiles a list of contrasts such as to

on have, s on has in He has to go, and the possibility of Having to go but not of

Musting go. This leads into a discussion of how to choose between the two when

writing, which then broadens out to include other modal verbs such as may and can,

and the differences between them. The discussion is a discussion among equals

because all the students use these verbs every day, so they are already experts; what

they like is explicit awareness of the choices they have to make.

The next lesson is French, which again starts with a warm-up exercise. This

time it’s about how possession is expressed. The teacher presents half a dozen French

sentences such as Jean touche la valise de Marie and Jean touche la main à Marie.

The question for the students is how to choose between de and à. Once they work out

the difference between ‘alienable’ and ‘inalienable’ possession, the teacher directs

their attention to English sentences like John touched Mary on the hand, and asks if

this might have something to do with the same contrast. By the end of the lesson, the

students have a good understanding not only of terms such as ‘possession’ and

‘alienable’, but also a better understanding of how languages can be both similar and

different at the same time. They have also, on the way, learned and practised the

French patterns, but they will return to these in the next lesson.

Then they move into a maths lesson. The subject is algebra, and in particular

the technique of expanding brackets as in 3 x 63x 18. The teacher, who (of

course) is well-versed in grammar, points out that something very similar happens in

coordination, where He sang and danced can be expanded into He sang and he

danced. He reminds them of the notation for coordination which uses brackets, as in

He (sang and danced). This incident only occupies a few minutes in the middle of the

lesson, and illustrates the benefits of being able to call on grammatical understanding

at any point.

Similarly, history mentions some grammatical points in an old document, and

chemistry mentions the similarity (familiar to linguists) between the ‘valency

bonding’ of atoms and the ways in which words hang together in a sentence. He also

shows how the word “polyvalent” can be analysed into “poly”, “val” and “ent”.

Citizenship mentions the grammatical choice between first and second person as the

basis for any face-to-face interaction, and biology touches on the debate about

whether grammar is innate or learned.

Several teachers comment on grammatical issues in children’s written work.

The history teacher briefly mentions the choice between “Henry the Eighth’s second

wife” and “the second wife of Henry the Eighth”, and the chemistry teacher points out

how the link between “valent” and “value” helps to remember that both words have

just one ‘l’.

Grammar, in short, pervades the whole curriculum in much the same way as

numeracy and literacy.

But that’s not all, because enthusiasts go off at lunchtime for the weekly

‘Linguistics Club’ run by the French teacher, who is preparing for the annual UK

Linguistics Olympiad11. This is an academic competition for schoolchildren like the

Maths Challenge, but focusing on language problems. The challenge is to work out

how the language concerned ‘works’, and some (but not all) of the problems involve

grammar. This week the problem is from Ulwa, a Nicaraguan language, where the

earlier discussion of French possessive patterns prepares them to work out the much

more complex system of Ulwa, where siknibilh, ‘our (inclusive) horsefly’ consists of

sikbilh with ni inserted right in the middle. Among other things, students learn to talk

comfortably about infixes.

****

At this stage in the argument I would expect some readers to roll their eyes

and wonder what planet I’m on. Surely it’s ridiculous to imagine so many people

knowing so much grammar? And especially so in the harsh reality of 2012, where

most teachers have themselves come through a completely grammar-free education at

both school and university?

In any case, is this a good use of resources, compared, say, with basic literacy

or numeracy? What’s the point of training the population to think about grammar

when the bills aren’t being paid?

I recognise these objections and take them seriously, but the point of this book

is to confront them and answer them. The first objection can be dealt with relatively

easily. The scenario I described is totally realistic, in a global sense, because it’s a

minor variation on what happens already in some countries. For instance, a recent

description12 of grammar teaching in The Netherlands reported that ‘teachers seem to

like to teach grammar’, so they do more of it than is strictly required by the

curriculum. For such teachers, it is very easy to imagine them including warm-up

activities on grammar, and freely using grammatical terminology in the same way as

they might use terminology from any other subject area. Nor is the ‘Linguistics Club’

fantasy – it’s already happening in the UK. Some schools really do run just such a

club, and do enter children for the UK Linguistics Olympiad. In fact, as of 2012, two

thousand children and 300 schools are involved in the Linguistics Olympiad at some

level, and the numbers are rising fast.

The second objection is harder to counter: even if grammatical analysis on this

scale is possible, is it desirable? And in particular does it justify the considerable cost

of bringing teachers up to speed in grammar? These are the main questions for this

book.

11

http://www.uklo.org.

Position paper on ‘The place of grammar in the L1 curriculum in the Netherlands’,

by Gert Rijlaarsdam, 2011; prepared for ‘Stakeholder Conference: Re-thinking

grammar and writing’, 3rd February 2012

12

It should be clear from this scenario roughly what I mean by ‘grammatical

analysis’, but just to avoid misunderstanding I’ll now spell out what I am not

advocating.

I’m advocating grammatical analysis, which is an important part of linguistics,

but that’s as far as I go in this book: I am not advocating a general course in

linguistics. Of course, as a linguistician13, I would love to see every child covering a

lot of elementary linguistics – how children succeed in learning language but

chimpanzees fail, how dialects evolve and differ, how we make consonants and

vowels with our mouths, how vocabulary divides up the world in a systematic way. I

also believe passionately that education would be greatly improved by a stiff dose of

elementary linguistics. But that’s not the argument I’m making here. This book really

is just about grammar. I’ll explain more precisely what that means in section 6, but for

the present it’s enough to say that it’s about how words are organised to convey

complex meanings.

Nor am I advocating a return to prescriptive grammar. Prescriptive grammar

‘prescribes’ (recommends) some forms and ‘proscribes’ (bans) others; it prescribes I

haven’t and proscribes I ain’t; it prescribes the book in which I found it and proscribes

the book I found it in; and so on. In contrast, grammatical analysis accepts any form

that’s in regular use, and analyses it. That doesn’t mean simply stamping it as ‘ok’; it

means pursuing all its characteristics, including the social differences between haven’t

and ain’t, and trying to understand the dynamics of the system – how ain’t fits into

the larger system of auxiliary verbs. I reject prescriptive grammar totally, as really

bad science; but I don’t reject the goal of teaching standard English as a supplement

to local non-standard varieties. I just think that prescriptive grammar isn’t just bad

science, but it’s also bad pedagogy because it rejects outright so much of what

children already know. Instead of undermining this knowledge, we should be building

on it as a firm foundation. I have more to say about the flaws in prescriptive grammar

in section 3.

Nor am I advocating a simple return to the grammatical analysis that used to

exist in some schools, and that still happens in some. Grammatical analysis was part

of the official curriculum till some time in the 1960s, but since it died in most schools,

grammatical analysis has been re-born in our universities and grown spectacularly.

There’s no need to look backwards for a model, because linguistics offers many

excellent models (section 6).

2 My credentials

This is a very personal statement of beliefs, so readers need to know how seriously to

take it. At this point I face a dilemma, because English people are deeply reluctant to

boast. How does one present one’s credentials without boasting? I take comfort from

the fact that my first ‘boast’ is that I’m a grammarian, which for some people isn’t a

boast at all, but a confession.

My credentials in this campaign start with my years at secondary school,

where I learned a lot of grammar and enjoyed it immensely. Those years, and that

expert teaching, turned me into a grammarian for life, so after a remarkably grammarMy colleagues in linguistics like to call themselves ‘linguists’, but they also grumble about the

confusion that this term causes by lumping them together with the ‘linguists’ of the worlds of education

(where anyone who studies a language is a linguist) and business (where the Chartered Institute of

Linguists exists for professional translators, interpreters and others who make a living from language).

The solution lies in our hands: if we call ourselves ‘linguisticians’ nobody will ever confuse us with

linguists of other kinds; and, as a bonus, it will emphasise our similarity to phoneticians.

13

free undergraduate course in French and German, I did a PhD on grammar (in this

case the grammar of an unwritten language spoken in the Sudan, Beja) and then spent

the rest of my working life teaching and researching grammar at UCL14. So I know a

great deal about the world of grammar as practised at university by linguisticians – a

world which has had hardly any impact on school teaching.

Although a linguistics department can be very much like an ivory tower, I

actually spent a lot of time looking out at the very different world of schools. This

was largely because I worked for a few years with a brilliant bridge-builder, Michael

Halliday, whose work with schools I very much admire15. Following his inspiration, I

was a founding member in 1980 of the Committee for Linguistics in Education16,

whose mission was (and still is) to build bridges between linguistics and schools; and

as of 2012 I’m an active member of this committee (which celebrated its hundredth

meeting in early 2012). But the work I take most pride in is the UK Linguistics

Olympiad (which I mentioned earlier), where I chair the committee that CLIE created

in 2009.

I’ve also worked quite a lot with government departments on documents such

as curriculums and materials about grammar. I had a hand in a heavily revised

glossary for the National Literacy Strategy17, in a very well-received book for primary

teachers called “Grammar for Writing”18, in guidelines for teaching foreign

languages19, in the specifications for the ill-fated Diploma in Languages20, and in the

grammar component of the new National Curriculum for English21 promised for 2013.

I have also written training material about grammar for secondary teachers22, and a

rationale for the grammar component of the old Literacy Strategy23. So I know what

the existing government documents say about grammar.

Unfortunately I also know that there’s a gulf between government documents

and the reality in the classroom. In 1986, a colleague and I tested the very elementary

grammatical knowledge of the school-leavers who were most likely to know any

grammar, namely the new undergraduates in a department of linguistics or of foreign

languages. The test was very simple, consisting of a sentence in which students had to

find a noun, a pronoun, a conjunction and so on through fifteen word classes. This

little project took place before the 1990 National Curriculum first laid down the

minimum standards for grammatical knowledge, so when I repeated it (with a

different colleague) in 2010 we should have found a significant increase in

knowledge. In fact, we found that students knew even less grammatical terminology

in 2010 than they had in 1986. I mention this little project as evidence that I’m

enough of a realist to recognise the formidable obstacles that have to be overcome

between where we are now and the imaginary world of section 1. I discuss some of

these obstacles in section 8.

One important qualification for writing this book is breadth of both vision and

experience. As a linguist, I see the whole of language education as a single complex

14

My website is http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/home.htm.

Halliday 2007

16

http://www.clie.org.uk

17

This revised glossary is included in one on my website:

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/tta/glossary/KS2&3.htm

18

Anon 2000

19

The guidelines are no longer available online.

20

Launched in 2008 and abandoned in 2010; see http://www.linksintolanguages.ac.uk/news/786.

21

http://www.education.gov.uk/schools/teachingandlearning/curriculum/nationalcurriculum.

22

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/tta/KS3.htm

23

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/kal/top.htm

15

network, whether it concerns a child’s first language or a foreign language. (Among

linguists and educators this view is called ‘Language awareness’24.) Remarkably few

government documents bring these two strands of teaching together (unlike my own

schooling, where the same teacher taught English and Latin). Indeed, even within

first-language English teaching there seems to be a significant division, at least in

research, between thinking about reading, writing, speaking and listening; this

division is crucial when discussing grammar because grammar is much more closely

associated, in teachers’ minds, with the teaching of writing than of any other

modality.

As a bridge-builder, I also see universities as part of the same educational system

as schools, with universities receiving students from schools but also providing

teachers and expert knowledge. Again this holistic view is rather rare, especially in

universities (which tend to see themselves as victims of the school system rather than

as colleagues).

One final qualification for writing this book takes me back to the research world

of linguistics, and of grammar in particular. This world has been growing and

changing very fast since the 1950s, with two kinds of product to show for all the

activity. On the one hand, we now know a great deal about grammar, and in particular

about the grammar of English, which we didn’t know sixty years ago. And on the

other, we have a large collection of general theories of grammar – how sentences and

words are structured, and how grammars can say what’s possible and what isn’t. I

know quite a lot about these theories, so I know which ideas are safely

uncontroversial and where the theoretical minefields lie. (In fact, in 1980 I compiled a

list of 83 claims that were uncontroversial in linguistics25.)

My view is that the last thing schools need from linguistics is to get mired in our

research controversies, but I also have to declare a vested interest because I myself

invented one of these packages (called Word Grammar). Not surprisingly, I believe

that Word Grammar is better than any of the others; but I also believe that it has

something rather special to offer schools which no other theory does. I’ll explain this

in section 6, where I shall also note that my suggestion is controversial among my

professional colleagues.

I would like to think, therefore, that as an elderly, experienced, research-expert

and broad-minded academic I have some hope of offering the ‘joined-up thinking’

that seems so hard to achieve, and that is certainly quite unusual in the area where it is

arguably most needed: education.

3 A brief history and geography of grammar teaching

Grammar has an extremely respectable ancestry. The earliest evidence we have26 is

from nearly 4,000 years ago, when the Akkadian-speaking scribes of Babylon learned

to translate into Sumerian (which by then was already dead). Their training included

learning tables of equivalent verb-forms in the two languages, so someone must have

analysed these verb forms and produced a systematic framework. Rather remarkably,

they ordered first, second and third person forms in that order, so that particular part

of our heritage may be four thousand years old – a spectacular example of scholarly

transmission.

24

The best place for an introduction to Language Awareness is

http://www.languageawareness.org/web.ala/web/tout.php.

25

Hudson 1981

26

Gragg 1994

The term ‘grammar’ comes from the Greek expression grammatike tekhne,

meaning "art of letters," which also contains gramma "letter", so its modern meaning

is a narrowing of the original, though it is still closely associated with writing. The

Greeks developed the tradition of grammatical analysis that dated back to the

Babylonians into a more highly structured and theoretical system – or, more

accurately, a series of different and competing systems – which linked not only to

school teaching but also to philosophy27. Somewhat later, the Romans adopted this

legacy and applied it to Latin, forming the basis of the European grammatical

tradition which survived, with remarkably little change, into the nineteenth century.

For the Greeks and Romans, the school curriculum (called ‘the liberal arts’)

had just three parts, one of which was grammar. (The other two were logic and

rhetoric.) This tradition persisted through the Middle Ages, with Latin still as the

medium of instruction; so grammar was essentially the grammar of Latin, rather than

of English. Grammar dominated the entire curriculum, a fact which we celebrate in

the name we still give to some of the schools which were founded in the late Middle

Ages (or their more recent equivalents): ‘grammar school’. By the nineteenth century

the school curriculum had broadened considerably, but in public schools and grammar

schools grammar still played a significant part in the teaching of foreign languages

(modern as well as classical) and in the teaching of English.

How significant is ‘significant’? In foreign-language teaching the dominant

approach is now called the ‘grammar-translation’ method28, a name which reflects the

centrality of grammar. Another indication of significance is the supply of textbooks,

which in the early twentieth century were solid, serious, rather dull and widely used.

For example, in French the dominant textbook author from at least the 1930s to the

1960s was W. F. H. Whitmarsh, M.A. (the ‘M.A.’ is important as a sign of academic

reliability), who wrote several dozen textbooks for schools. English grammar was

similarly dominated by a single figure, J. C. Nesfield, M.A. (again), whose ‘Manual

of English Grammar and Composition’29 was first published in 1898 and was so

influential that it spawned a further generation of derivative textbooks. Nesfield’s

textbook is nothing if not solid: 418 pages of tiny print, with the first hundred devoted

to grammatical analysis. The detailed discussion of word classes has a clear and

ambitious purpose: to prepare students to apply a standard grammatical analysis to

any sentence a teacher or examiner might throw at them. The only other subject that

had, or has, a similarly ambitious goal is mathematics. One interesting characteristic

of Nesfield’s grammar is the standard table for laying out the parts of a sentence; this

is an example of the notation for which I shall argue in section 6.

This educational tradition was shared, by and large, by all of Europe, and

indeed it was exported to the overseas colonies and territories. In many of these

countries, grammar still has its traditional status and content, albeit with some features

modernised. In most of Eastern Europe, school children still spend significant

amounts of time learning how to analyse words and sentences in their own language,

and build on this grammatical understanding when learning foreign languages; and

the same is true in most countries whose language is descended from Latin (such as

Italy, Spain, Portugal and France, and their overseas extensions)30. It’s hard to know

27

Robins 1967

For a brief discussion and exemplification, see http://www.nthuleen.com/papers/720report.html.

29

Nesfield’s book can be read online at http://archive.org/details/manualofenglishg00nesfuoft.

30

For instance, a group of undergraduates from a Spanish university took a test (in English) that we

used for assessing UK undergraduates’ knowledge of grammatical terminology, and outperformed all

the UK groups.

28

how successful this teaching is, especially without knowing what its precise goals are;

but one measure is popularity among adults who ‘did some grammar’ at school. The

fact is that a lot of people hated it, but (by an admittedly crude measure31) even more

loved it.

However, the UK was different. In this country, grammar-teaching more or

less disappeared in the 1960s, as it did in most other English-speaking countries32.

The reasons for ‘the death of grammar’ are complex and deserve more research, but

one element in the explanation is certainly the lack of grammatical research in our

universities throughout the early twentieth century33. This left universities with

nothing to teach their undergraduates about grammar, and therefore no intellectual

boost for future school teachers comparable to the updating and rethinking that

undergraduates receive in other subjects.

The result was a decline in the teaching of grammar in English lessons, with

teachers applying half-remembered analyses from their own school days and using

textbooks based directly on the previous generation of school textbooks, without any

academic input. Some teachers still inspired (as mine did), and some children still

enjoyed their grammar classes (as I did); but most grammar lessons were boring,

dogmatic and intellectually frustrating. It is hardly surprising that English teachers

started to ask what the point was, and welcomed with open arms a series of research

projects which showed that grammar lessons had no impact at all on the quality of

children’s writing34. Since the standard argument for grammar was that it improved

writing, this research was the end of grammar teaching – much to the relief of a great

many people who had been campaigning against grammar and in favour of literature.

The effect was that in the early 1960s the one remaining optional question about

grammar was removed from the O-level English paper, and, effectively, grammar

died in English. Seen from a global perspective, English (and England) had entered

the Grammatical Dark Ages. Meanwhile, of course, all was by no means doom and

gloom in English teaching, “in which at last a subject in the curriculum engaged with

students’ voices, imaginations and responses in a way which is widely seen as being

one of the most positive developments in school subject teaching of the 20th

century.”35

Meanwhile, of course, grammatical knowledge was needed in foreignlanguage teaching so long as this was dominated by the grammar-translation

approach. This kind of teaching became increasingly difficult as more and more

English teachers abandoned grammar, but foreign-language teaching had its own

agenda, and grammar-translation gave way to other approaches in which grammar

was less central. The new ‘communicative’ syllabus, with its focus on knowing how

to carry out very specific tasks in the target language, allowed teachers (and text-book

writers) to replace grammar by memorized phrases. Although more recent research

has confirmed that students learn foreign languages better if teaching focuses

explicitly on grammatical or lexical forms, with or without attention to meaning,36

In May 2012, Google found 77,000 examples of ‘I hate grammar’ compared with 162,000 of ‘I love

grammar’.

32

Australia and New Zealand had a similar history to the UK. Although the USA shared in the

grammar debates of the 1960s, grammar teaching seems much more common in English lessons there

than here; but it also seems to be more focused on avoiding ‘errors’ than on grammatical analysis per

se. I don’t know the state of grammar teaching in Canada, Ireland or South Africa.

33

Hudson and Walmsley 2005

34

Andrews and others 2004b, Andrews and others 2004a, Andrews 2005

35

Gary Snapper, personal communication

36

Norris and Ortega 2000

31

foreign languages are often taught without any use of grammatical terminology. It is

interesting to wonder whether foreign-language teachers would have adopted the

communicative approach so enthusiastically if their pupils had come to them with a

good supply of grammatical terminology learned in English.

The main point of this brief history and geography is that normal schooling

does include grammar teaching, so there is nothing ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ about

ignoring it. On the contrary, grammar played a central role in Western education for

thousands of years, and continues to do so in many countries. We are the ones who

are out of step, and the term ‘Dark Ages’ that I used earlier really is justified as a

description of the grammar-free education that most of our children have received.

However, this situation can be seen as an opportunity for a new start.

Paradoxically, while grammar has been ignored in schools, it has flourished in

university research and teaching. In 1921 it was possible to write37 that it was

“…impossible at the present juncture to teach English grammar in the schools for the

simple reason that no-one knows exactly what it is…”; nearly a hundred years later,

we know a great deal about English grammar, thanks to a series of block-buster

research-based grammars.38 At the same time, a good deal of linguistic thinking (short

of grammatical technicalities) have found a place in schools, so teachers are used to

teaching about non-literary genres, spoken language and variation. Most importantly

of all, perhaps, Standard English has taken its place among a range of alternatives

which are accepted as equally ‘correct’ in their own terms. With this background,

both academic and pedagogical, a new version of school grammar can be developed

which is much better than what was taught in the nineteenth century.

4 Why, what and how

I now turn to the case for grammatical analysis – what I shall now call simply

‘grammar’, though I shall spell out the exact meaning in section 6. Why should it be

taught, what should it consist of, and how should it be taught? These three questions

are obviously closely connected.

For example, if the main reason for teaching grammar is to allow English

teachers to deal with ‘common grammatical errors’, then we immediately have an

answer to ‘what?’: grammar consists of whatever terminology is needed in order to

define these mistakes. For instance, if one of the errors is so-called ‘split infinitives’,

then children should be taught to recognise infinitives and name them. This in turn

suggests an answer to ‘how?’: rather didactic lessons in which the teacher goes

through errors one at a time, providing an example, a name for the error, a definition

of the error and its correct alternative, possibly an explanation for why it is an error,

and then an exercise in which students spot examples of the error and correct them.

Needless to say, this is not the kind of teaching that I have in mind, but that is as

much because I reject the initial motivation (why?) as because I reject the content

(what?) and the method (how?).

What I shall argue below is that there are many good answers to all three

questions, though the answers are to some extent interconnected in the way suggested

above. It will be helpful to separate out the different answers to each question, if only

for intellectual clarity, though in some cases it may be possible to combine answers;

for example, it is surely possible to combine different aims in a single lesson. But it

37

Board of Education 1921

Quirk and others 1972, Quirk and others 1985, Biber and others 1999, Carter and McCarthy 2006,

Huddleston and Pullum 2002.

38

will certainly not be helpful to continually look across from one question to the

others. In discussing the educational benefits of grammar (why?) it will only be

confusing to bring in further questions about the content of the grammar (what?) and

the pedagogical methods (how?). These links are important, of course, but for my

purposes they will complicate the argument unnecessarily so, by and large, I shall

ignore them.

5 Why?

Why, then, should grammar be taught? For some teachers, the only driving force is

‘because The Boss says so’, where The Boss could stand for various figures ranging

from Head of Department, through Head Teacher, to the Secretary of State for

Education. This is to be expected, given the powerful campaign that finally removed

grammar from the curriculum. For decades, teacher-trainers have been telling trainee

teachers that teaching grammar is a waste of time, or worse, and it is common to hear

grammatical analysis described as merely ‘the naming of parts’, a pointless exercise

in classification. As I shall explain in section 6, such comments miss the point almost

entirely, but the fact is that these views are influential.

There are, in fact, some very good reasons for teaching grammar, and

improving writing is only one of them – an important reason, but by no means the

most important one. The debate about the pros and cons of grammar teaching had

such a negative outcome in part because it focused almost exclusively on this reason,

ignoring all the others – improved reading, foreign-language learning and general

thinking skills. Imagine a similar debate about the pros and cons of teaching algebra

which focused entirely on the benefits for domestic account-keeping and concluded

against algebra on the grounds that it doesn’t help people to avoid debt. One of the

purposes of this book is to restore the balance in the debate about grammar by

presenting a broader picture.

One important consequence of looking beyond any one aim of grammar

teaching is to reframe the debate about the benefits of teaching grammar. Like any

other teaching activity, teaching grammar has a cost, in terms of time that could be

devoted to other worthwhile activities, in terms of teacher training and in terms of

pupil commitment. The debate is about whether this cost is balanced, at least

subjectively in the eyes of teachers, by educational benefits to the pupils, so it is

important to have a clear global view of both the costs and the benefits. If grammar

teaching produces benefits in just one area, such as writing skills, these benefits must

balance the total cost of teaching grammar from scratch. But if the benefits are spread

across a wide range of areas, the cost per area is clearly much lower.

To see the importance of this point, consider two contrasting scenarios. In the

actual current scene, children know very little grammar when they leave primary

school, so any secondary teacher who wants to mention grammatical concepts must

teach not only the concepts concerned, but also a whole raft of elementary ideas

which underpin them. Historically, this is the situation in which foreign-language

teachers found themselves in during the 1970s when English teachers stopped

teaching grammar, and it is hardly surprising that grammar-free teaching methods for

teaching foreign languages became so popular. Now consider the scenario that exists

in some countries, in which children learn and consolidate a great deal of grammar in

primary school. By the time they reach secondary school, basic grammatical concepts

and terminology are familiar, so there is no cost at all to using them – indeed, the

more they are used, the more firmly they become entrenched in children’s minds.

Admittedly a secondary teacher may need a specialised concept that the children have

not yet learned – such as ‘modal verb’, ‘subjunctive’ or ‘ablative’ – it will be

relatively easy to teach because children already understand foundational concepts

such as ‘verb’, ‘subject’ and ‘subordinate’. In this scenario, grammar is virtually costfree in secondary schools, and its costs in primary are offset against a wide range of

benefits in secondary.

5.1 Writing

The first reason, then, is the one that most educationalists have concentrated on for the

last few decades: teaching grammar improves first-language writing skills. The

argument is that mature academic writing (the target of school literacy teaching)

requires high-level linguistic skills, including not only a broad vocabulary but also

sophisticated grammatical skills. These skills are of two kinds, negative and positive:

standardness, meaning the avoidance of forms from the local Non-standard

dialect (e.g. ain’t); this is sometimes called ‘accuracy’ or ‘correctness’.

diversity, i.e. the sensitive use of a wide range of constructions, including

constructions that aren’t normally used at all in ordinary conversation (e.g.

While working in the garden he injured himself).

Until very recently this argument has carried very little weight in the Englishspeaking world because of the research (mentioned earlier) that purported to show

that teaching grammar simply did not work as a way of teaching either kind of skill.

However this research had a fundamental flaw: all it showed was that grammar can be

taught ineffectively. Typically, a class would have (say) a weekly lesson on grammar,

and their written work would be compared with that of another class that had no such

lesson. The results showed that grammar is ineffective when taught in this way; but it

did not show that this was the only possible way to teach grammar.

The received wisdom has been overturned by two recent strands of research,

both conducted in Britain. Since the 1990s, the psychologists Peter Bryant and

Terezinha Nunes and their colleagues in Oxford have shown that explicit instruction

in morphology (the grammar of word-structure) does indeed produce measurable

positive effects on children’s spelling, their use of apostrophes, and the growth of

their vocabulary39. For example, children were better able to distinguish plurals and

possessives in pairs such as boys and boy’s after practising morphological analysis

than when the practice involved just pronunciation or just meaning and syntax

(sentence structure)40. More recently, the educationalist Debra Myhill and colleagues

in Exeter have shown considerable benefits in a large-scale study from ‘focused’

teaching of specific grammatical patterns; for instance, discussion of modal verbs

such as may and must produced benefits in the children’s use of modal verbs in their

own writing41. Teaching is focused, in this sense, if it concentrates on patterns which

are then tested in the children’s writing. This is an important qualification, which I

return to in section 7, because one of the main problems with previous research was

that the teaching was unfocused, so what was tested bore only a very general relation

to what was taught – a rather obvious weakness.

39

Nunes and Bryant 2006

Bryant and others 2004

41

Myhill and others 2010

40

Another important strand of research, this time from America, gives somewhat

weaker support for teaching grammar42. This research shows that a classroom activity

called ‘sentence combining’ is good for the children’s writing skills. In sentence

combining, the teacher provides two or three single-clause sentences for the class to

combine into a single sentence. For instance, given the sentences (1) The boys were

playing with the dog. (2) They were standing on the pavement. (3) It was barking

loudly, a class might synthesize a wide range of sentences including the following:

The boys who were standing on the pavement were playing with the dog that

was barking loudly.

The boys standing on the pavement were playing with the loudly barking dog.

While standing on the pavement, the boys were playing with the dog barking

loudly.

Although it was barking loudly, the boys standing on the pavement were

playing with the dog.

The research shows that this activity has a strong positive effect on writing quality.

The only uncertainty is about whether the activity can really be called ‘teaching

grammar’. Most of the research literature rightly contrasts it with grammar teaching

as this is normally interpreted, at least in the States. But as I shall explain in section 7,

there are many ways of teaching grammar, and a good case can be made for

recognising sentence combining as one of these methods, whether or not the teacher

or students use technical grammatical metalanguage.

I introduced this discussion of writing skills by distinguishing negative

standardness and positive diversity. Both are legitimate targets of grammar teaching if

the aim is for every school leaver to be able to write mature standard English, but the

research that shows the positive effects of grammar teaching has focused on diversity

rather than standardness. This is reasonable because the two goals are very different.

Teaching children to write isn’t rather than ain’t is intellectually very easy, but may

raise emotional problems for children who use ain’t in their family, especially if ain’t

is labelled simply ‘wrong’ (or even worse, ‘bad’). This kind of teaching is often based

on a list of ‘common grammatical errors’ which has been handed down from one

generation of school teachers, via their pupils, to the next. In contrast, teaching

children to use a wider range of modal verbs is intellectually difficult (because of the

subtle meanings involved), but emotionally easy since it doesn’t threaten the

children’s identity. Moreover, it is rather obvious that telling children to avoid ain’t in

writing does have an effect, because most school leavers do avoid it in writing even if

they use it in speech; whereas the received wisdom was that merely telling children

about modal verbs would have little or no effect on their use of modal verbs. The

main point to emerge from this subsection is that this is wrong. Focused teaching of

specific grammatical points does indeed increase the diversity of children’s writing.

5.2 Reading

Another argument for teaching grammar is in improving reading skills. This is where

it is important to stress that ‘grammar’ means grammatical analysis rather than mere

error-avoidance. If the teaching of grammar was all about avoiding forms such as

ain’t, it would be irrelevant to reading; after all, it is the author rather than the reader

that chooses what words to use. In contrast, grammatical analysis is highly relevant to

reading because it is simply a conscious and articulated version of the analysis that

any reader makes. To read a sentence is to analyse it – its words, its grammar and,

42

Andrews and others 2004b

ultimately, its meaning. The only differences between ordinary expert reading and

grammatical analysis are that the latter is completely conscious and reflective, that it

is explicitly expressed in terms of a standard terminology and notation, and (of

course) that it is much, much slower.

Grammatical analysis helps children’s reading in two ways, one very specific

and the other global. Specific grammatical instruction helps children when reading

sentences with particularly difficult syntax. The evidence for this claim comes from

research by Ngoni Chipere43, working with non-academic 18-year olds. The task for

his subjects was to read complex sentences like The doctor knows that the fact that

taking good care of himself is essential surprises Tom, and then to answer questions

such as What does the doctor know? or What surprises Tom? All the sentences had a

similar syntactic structure, so it was possible to train some subjects in handling

sentences with this structure by showing them how to break the sentences down into

simpler sentences and then to recombine these. The experiments showed that this

training had a clear positive effect on comprehension skills, so trained subjects

understood the sentences better than untrained subjects did. Like the research on

writing reported above, this research shows the benefits of highly focused grammar

teaching in which the construction taught is also the one tested in the research.

Turning to the global benefit of grammar teaching for reading, this is more a

matter of conjecture than of research, but it is so plausible that it should be taken

seriously. The claim is that grammar teaching encourages pupils to pay more attention

to grammatical structure in their reading – in other words, to ‘notice’ it44. When we

meet a difficult or unfamiliar word or structure, we can react in different ways. At one

extreme, we can stop and look at it to puzzle out what it means and how it works. This

is more likely if we are used to grammatical analysis because that is precisely what

such analysis consists of: working out how the parts of a word or sentence fit together

and produce their joint effect. At the other extreme, we can give up on grammar and

guess the meaning. This is what most of us do with sentences such as this: No headwound is too trivial to be ignored45. This apparently simple sentence is remarkably

hard to understand, as you will confirm by considering its opposite: No head-wound is

too trivial to be treated. I would guess that you found this just as sensible as the first,

but they can’t both be sensible. In such cases, we switch off the normal rules of

grammar and rely on common-sense.

Between these two extremes are constructions that most of us read but don’t

hear, such as the house in which he lives. If the goal is simply to extract meaning, a

reader can simply ignore the position of in; but a reader who finds syntax interesing

will pause and absorb the syntactic detail. There is ample evidence that syntactic

knowledge grows throughout the school years46, and that one of the main models –

perhaps the main model – for young writers is the material that they read. Moreover it

is clear from errors such as the house in which he lives in that novices struggle to

understand sophisticated constructions; so the more attention they pay to the

sentences they read, the more effectively they will learn to use such constructions

themselves. But paying attention to syntax is a waste of time if the only aim is to

extract meaning. Some children are natural ‘noticers’, but many are not; and (so the

argument goes) it is for the second kind of child that grammar teaching is particularly

important. Of course the grammar teaching for writing may focus on particular

43

Chipere 2003

Keith 1999

45

Wason and Reich 1979

46

Perera 1984, Hudson 2009

44

constructions, such as in which, which children need to learn, but there is simply too

much grammatical detail to teach it all in classroom time, so the best strategy is to

provide a general tool which will allow children to learn from their reading.

One particularly important kind of reading where grammatical analysis is

especially helpful is the reading of literature – stories, novels, poems and so on.

Literary works that are read in class are, by definition, well written, so they serve as

an excellent model for linguistic novices. And indeed, one of the main arguments for

linking literature to language-teaching in English is that children will become better

writers through reading literature. As we all know, mere ‘exposure’ works for some

children, but not for all, and maybe those for whom it does work are those who are

naturally inclined to ‘notice’ the grammar and vocabulary of what they read. If so,

then small amounts of carefully focused grammatical analysis may help the others to

notice, and learn. I give an example in section 6 of this kind of analysis.

5.3 Speaking and listening

Although grammar is historically associated with the written language – after all, in

Greek gramma meant ‘letter’ – it is highly relevant to the spoken language as well

because this is the source of written language. Spoken language, including the most

spontaneous and casual conversational styles, is controlled by much the same

grammatical rules as the most formal writing, even if real-time production allows

slips of the tongue and disfluencies that would be edited out in writing. A sentence

such as I love you comes out the same whether written or spoken, and has different

syntax from its equivalent in other languages such as French Je t’aime, Latin Te amo

or Arabic Ahibbik.

One of the very positive recent changes in our school curriculum is the much

higher profile that we now give to the spoken language in both first-language English

and foreign languages. Grammatical analysis has an important contribution to make in

teaching about spoken language. I consider here first-language English, leaving

foreign languages till the next subsection, and distinguish three different kinds of

contribution: transcription, status-raising and detail.

Transcription of spoken language is an important exercise for any child47. It is

easy to record conversation, and given a recording, any child can transcribe it; and of

course if that child happens to be a participant in the conversation, so much the more

interesting for them. One of the lessons that emerges from this activity is that any

transcription goes well beyond the purely phonetic substance of the recording. The

transcriber makes decisions about words (e.g. wait or weight?) and about grammatical

structures (e.g. fun and games or fun in games?), so a transcription is, in effect, a

grammatical analysis. This is particularly true if the transcription includes

punctuation, since this forces decisions about sentence-boundaries and other major

structural distinctions. Discussing these decisions in class is a useful way of

sharpening pupils’ awareness of grammatical structure, but (of course) it presupposes

a shared framework of ideas and terminology – precisely what grammar teaching

provides.

Status-raising is particularly important for the large majority of children –

probably about 80-90%48 – who natively speak a non-standard variety of English.

47

For guidance, see the website produced for BT by Julie Blake and Tim Shortis at

http://www.btplc.com/Responsiblebusiness/Supportingourcommunities/Learningandskills/Freeresource

s/AllTalk/default.aspx?s_cid=con_FURL_alltalk

48

See Peter Trudgill: Standard English – what it isn’t, at

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/dick/standard.htm

Thanks to the very negative attitudes to non-standard forms (described variously as

‘wrong’, ‘careless’ or ‘bad’), schools traditionally left non-standard speakers with

quite unnecessarily negative feelings about how they spoke, described by some as

‘linguistic self-hatred’49. Even if schools aim to teach everyone to speak Standard

English when needed, there is no reason why this should not co-exist with the local

non-standard dialect in children who are essentially bi-dialectal. The challenge is to

make sure that children feel as proud of their local variety as they are of Standard

English, and the best contribution that schools can make is to treat them as different

but equal. In the case of grammatical analysis, this means objective comparison:

comparing them as equals, without implying that in some sense the local non-standard

is a poor copy of Standard English. For example, if the local dialect uses was after we

as well as after he, it is different from Standard English, but none the worse for it –

indeeed, the lack of a contrast in the past tense brings the verb to be in line with all the

other verbs, so the local dialect is more regular than Standard English.

The idea that grammar teaching might raise the status of non-standard dialects

deserves a little more discussion. One argument that helped to remove grammar from

the curriculum was that teaching Standard English was inherently prescriptive,

prescribing the forms of Standard English and proscribing non-standard forms. In

prescriptive grammar, we were and those books are correct, and we was and them

books are simply wrong. If this kind of grammar teaching makes pupils feel bad, not

only as speakers but as people, then perhaps all grammar teaching should cease50. The

approach that I am suggesting reverses this argument: grammatical analysis can be

purely descriptive (free of value judgements), so it can be applied as easily to nonstandard dialects as to Standard English and thereby raise the status of the former.

‘Detail’ is my name for the fine linguistic details that children need to know

when speaking and listening. These details include the features that distinguish the

local non-standard from Standard English, but go well beyond them to include any

patterns that are found in more formal or specialised discourse. Many of these are

simply carried over from formal writing, but some are not: more formal ways of

greeting people (e.g. good morning) and addressing them (e.g. sir), ways of

structuring discourse (e.g. by the way) and expressing degrees of certainty (e.g. didn’t

she?), and so on. Grammatical analysis can help children to broaden their range of

constructions in speaking in just the same way as in writing: careful study of recorded

speech not only reveals the new patterns in that sample, but also helps children to

notice new patterns in all their listening. Just as in writing, they have a myriad fine

details to learn before they count as mature competent speakers who can function

comfortably in a wide range of social settings.

However, it is important to recognise the lack of relevant research evidence

here as to how, or even whether, schools can help. It is easy to muster theoretical

arguments for or against the use of grammatical analysis as a tool for expanding

children’s repertoire of linguistic patterns for use in speaking. In its favour, it offers a

plausible way to help children to help themselves by learning from experience, which

is at least more promising than trying to teach all the details directly at school (given

the constraints not only time but also on our collective knowledge of what needs to be

taught). On the negative side, however, we simply don’t know whether it works –

whether a grammatical analysis of a recording, done in class, produces skills that

49

50

Macaulay 1975

Trudgill 1975

transfer to ordinary speech. The best I can say is that the idea is plausible, but needs

research.

5.4 Foreign languages

Until the 1960s, the dominant method for teaching foreign languages combined

explicit grammatical rules with translation exercises, so it is now called the ‘grammartranslation’ method. This obviously presupposed that pupils already knew a

substantial amount of grammar (both concepts and terminology), building on the

foundations laid in the English classroom. The method had serious weaknesses, not

least that it treated living languages in the same way as the dead languages, Latin and

Greek, for which it was originally devised, so ordinary conversational skills were low

on the agenda. The problems multiplied when grammar disappeared from English

teaching, so grammar (and translation) fell out of favour, to be replaced (eventually)

by ‘communicative’ methods based on the rather odd idea that learning a foreign

language in a classroom should follow the same pattern as learning ones first

language at home. The argument (encouraged by the fashionable linguistic theory that

language is innate) ran that since small children learned their first language without

the help of grammar, the same would be true for older children learning foreign

languages at school51.

This claim has been explored intensively by researchers, and refuted52. The

research shows that grammatical rules should be taught explicitly, using what is called

‘form-focussed instruction’, rather than left implicit in the hope that learners will

figure them out for themselves. Just as in first-language English, explicit grammatical

analysis encourages both noticing and understanding:

Why is metalinguistic activity [including grammatical analysis] on the part of

learners apparently so valuable? One reason can be found in [the] claim that

while awareness at the level of noticing is necessary for learning, awareness at

the level of understanding will foster deeper and more rapid learning.53

This does not, of course, mean that grammar is all we need, and it is certainly not a

reason to turn the clock back to the 1950s. We also know that learners need highquality input and high-quality interactive practice in order to turn this explicit

knowledge into the implicit knowledge that counts as skill in using a foreign

language. But it does mean that grammar can and should play a much larger part in

foreign-language teaching than it does currently.

5.5 Thinking

One of the traditional arguments for teaching grammar was that it was good mindtraining for the elite. A degree in the classics, with the grammars of Greek and Latin

as a major component, used to be considered an excellent training for the higher ranks

of the civil service. This argument is still just as valid as it used to be, except that we

can now generalise it beyond the academic elite. Some experience of grammatical

analysis is probably good for any mind, so long as it is pitched at the right level.

Unfortunately there is very little research evidence to support these claims, but

equally there is no evidence against them.

Grammatical analysis is very similar to mathematics in terms of the mental

demands that it makes. In both cases the learner has to learn a tightly-interconnected

51

Krashen 1982

Norris and Ortega 2000, Spada and Tomita 2010

53

Ellis 2008:452.

52

set of concepts such as: noun, subject, object, verb, modifier, adjective; these concepts

all help to define one another through statements such as “A verb’s subject is a noun”,

“A noun may function either as a verb’s subject or as its object” and “A noun may be

modified by an adjective”. In both cases the key concepts are relations between

entities rather than simple entities (e.g. ‘squared’ rather than ‘5’ in mathematics, and

‘subject’ rather than ‘noun’ in grammar). And in both cases it is essential to be able to

apply the analytical system to concrete examples, preferably examples from real life;

so just as the mathematician ‘thinks mathematically’ about some scenario, the

grammarian ‘thinks grammatically’ about a sentence or some other kind of text.

Moreover, both mathematics and grammar may be quite abstract, so

mathematicians consider the properties of the (non-existent) square root of minus 1,

while grammarians consider those of the missing subject in a sentence like Come

here! As in mathematics, a grammatical conclusion may lie at the end of a long chain

of arguments and assumptions, so grammatical reasoning can be very challenging;

and any step in the argument may be challenged on either theoretical or factual

grounds. The glory of both subjects is that it is possible – in fact, very easy – to be

wrong, and to be shown to be wrong.

Grammar, then, shares with mathematics the fact that it is a complex, abstract

system that can apply to concrete pieces of real or imaginary experience, and both the

system itself, and its application to a concrete experience, are subject to rational

debate. The most obvious difference between the two subjects is that mathematics is

taught at school, but grammar isn’t. Both subjects can be difficult to grasp and to

teach, so both need teaching methods tailored very carefully to the needs and abilities

of the learners. But nobody would argue that mathematics might be dropped from the

curriculum because of these difficulties or because some learners may not

immediately see their relevance. If we can find ways to teach mathematics to all, why

not grammar?

Indeed, grammar arguably has an even better claim than mathematics on time

in the school timetable. After all, grammar is about the basic organisation of language,

and language is our main tool for thinking and learning. Grammar isn’t an abstract

Platonic system like mathematics that exists ‘out there’; it’s part of our minds, the

product of thousands of hours spent, during childhood, listening to people round us

talking. English grammar is different, in fundamental ways, from French grammar

and Chinese grammar. It forces us to make distinctions, hundreds of times a day, that

French doesn’t force at all – e.g. the difference between it rained and it was raining –

and vice versa – e.g. the difference between tu and vous, or between voisin and

voisine (meaning ‘neighbour’, male or female). Some things are much easier to

express in one language than in another, such as different degrees and kinds of

uncertainty; and the associations embedded in two different languages may be quite

different (e.g. cycling is associated by the English verb to ride with horse-riding, but

by the German verb fahren with driving a car).

This is not to say that our language locks us into an intellectual prison from

which we can’t escape54; on the contrary, language is only one source of influence on

our minds. Another source is, as we all hope, education. Take the distinction which

54

This idea of language as an intellectual prison is the strong version of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis,

named after the two American linguists who most famously expressed it. Most linguists and

psychologists reject the strong version (Pinker 1994), though it survives in some versions of Postmodernism. However, a weak version of the Hypothesis, in which language is a major influence on

thinking, though not the only one and not necessarily on all areas of thinking, is widely accepted

Levinson 2003.

English forces on us between humans and everything else by making us choose

between the interrogative pronouns who and what. If you ask me: What broke the

window?, I could reply The wind, A falling slate or A bird, but not John – or at least,

not without some comment. In contrast, if you ask: Who broke the window?, I could

blame John but not the wind. This distinction lumps living creatures such as birds

together with inanimate things such as the wind and a piece of stone, in contrast with

humans. But we all know – thanks to education – that this classification obscures a lot

of similarities between humans and other living creatures, and a lot of differences

between either and non-living things like stones and the wind. A more ‘scientific’

classification would cut the cake very differently, so we have two very different

‘ontologies’ (ways of classifying things) to choose between, one basically driven by

language and the other by education and science. However worrying this may seem, it

doesn’t seem to be a problem, as every adult lives with both ontologies, and applies

them on different occasions as needed. But this ‘double-thinking’ is something we

should all be aware of, and where would we learn about it other than in grammatical

analysis of English?

Thinking goes beyond mere classification, and the most important questions

are those concerned with how things (or people) are related to one another. Is this an

example of that? Does this cause that? Is this an alternative to that? Did this happen

after that? The more abstract and complicated the reasoning, the more likely it is to

depend on language; and if we want to share it with someone else, we need a

symbolic medium such as a technical diagramming system, or ordinary language.

Seen from this perspective, it is essential for all of us, however academic or nonacademic we may be, to understand this basic tool, so that we are in command of the

tool, and not the other way round. And in particular, it is the general patterns of

grammar rather than the minutiae of vocabulary that we need to understand because

the general patterns are not only more general, but also harder to be aware of.

Fortunately I can finish this rather speculative section with some concrete

evidence that ‘doing grammar’ uses high-level thinking skills. The evidence comes,

once again, from the Linguistics Olympiad in which children as young as 12 years old

struggle to understand how some unfamiliar language works, with grammar

underlying most of the questions. I argued earlier that grammar requires very similar

mental skills to mathematics, and this claim is confirmed by the fact that most of

those who do best in our competition are also studying mathematics; indeed, some of

the champions in the International Linguistics Olympiad are also champions at the

International Mathematics Olympiad.

The next section will explain what it is in grammatical analysis that gives it this

hard, mathematical challenge. However, I shall also explain why it is also a ‘soft’,

humanistic and personal challenge, so that it combines the best of the two very

different worlds of mathematics and literature.

6 What?

What, then, is the grammar teaching that I have in mind? Much as I personally loved

the grammar teaching that was dumped from the curriculum in the 1960s55, the new