TEAM 498A - International Law Students Association

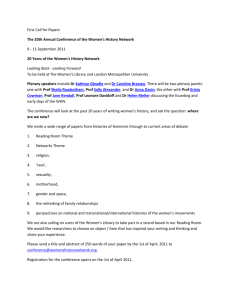

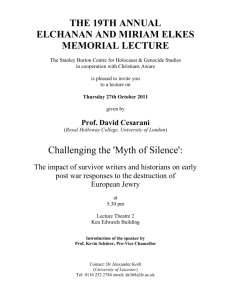

advertisement