icmemo1

advertisement

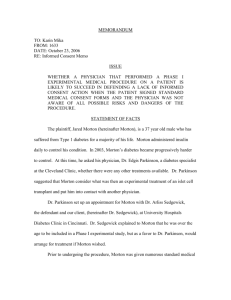

MEMORANDUM TO: Karin Mika FROM: 1111 DATE: October 19, 2006 RE: Dr. Arliss Sedgewick (lack of informed consent) ISSUE WHETHER A DIABETES PATIENT HAS A CAUSE OF ACTION FOR LACK OF INFORMED CONSENT WHEN THE DOCTOR FAILED TO INFORM THE PATIENT OF THE RISK OF KIDNEY FAILURE ASSOCIATED WITH AN EXPERIMENTAL TREATMENT. STATEMENT OF FACTS Plaintiff, Jared Morton (“Morton”), is a 37 year-old male suffering from Type I diabetes that, until recently, was controllable with daily insulin injections. In 2003, Morton’s diabetes became increasingly uncontrollable and he inquired of one of his physicians, Dr. Edgis Parkinson, whether there were alternative treatments available. Dr. Parkinson suggested an experimental islet cell transplant treatment being conducted as part of a study by the Defendant, Dr. Arliss Sedgewick (“Sedgewick”). Sedgewick is a diabetes researcher at the University Hospital Diabetes Clinic in Cincinnati. Upon consultation, Sedgewick made clear to Morton that he was over the age allowed for the study, but would be willing to include Morton as a favor to Dr. Parkinson. Morton was also provided a number of medical consent forms spelling out risks associated with the treatment and requiring Morton to assent to the judgments of the physicians overseeing his treatment. Morton, however, was not furnished the Phase I documentation concerning the experimental treatment, which detailed a 7% mortality rate, a majority due to renal failure, among lab mice that had undergone the treatment. Sedgewick disclaims any prior knowledge 1 of the mortality among lab mice due to her lack of familiarity with the research and lack of expert knowledge of the contents of the Phase I documentation. Additionally, at the time of commencing treatment on Morton, Sedgewick had no prior knowledge of renal failure among other patients in the study. In November 2004, Morton underwent the experimental procedure with seeming success. However, his diabetes returned by the seventh month following treatment, and Morton’s kidney functions began declining by the eighth. Within a year, Morton’s renal functions were failing and he was placed on the kidney transplant list. Morton filed suit in the spring of 2006 against our client, alleging medical malpractice and battery, on the grounds that he did not give informed consent to undergo the experimental treatment. DISCUSSION The general rule in Ohio concerning informed consent is that a physician must adequately disclose to his patient the probable consequences, material risks and anticipated benefits of a medical procedure. Congrove v. Holmes, 37 Ohio Misc. 95, 101 (Ct. Com. Pl. Ross County 1973). Actionable offenses for lack of informed consent have been further explicated by the Ohio Supreme Court in Nickell v. Gonzalez, 477 N.E.2d 1145, 1148 (Ohio 1985) as requiring three criteria be met: (a) The physician fails to disclose to the patient and discuss the material risks and dangers inherently and potentially involved with respect to the proposed therapy, if any; (b) The unrevealed risks and dangers which should have been disclosed by the physician actually materialize and are the proximate cause of the injury to the patient; and (c) A reasonable person in the position of the patient would have decided against the therapy had the material risks and dangers inherent and incidental to the treatment been disclosed to him or her prior to the therapy. 2 “[M]aterial risks” are such that a reasonable person “would be likely to attach significance to the risk of cluster of risks in deciding whether or not to forego the proposed treatment.” Id. at 1149; accord Bedel v. Univ. of Cincinnati Hosp., 669 N.E.2d 9, 14 (Ohio Ct. App. 1995). Concurrently, the specific determination of proximate cause must be assigned through expert medical testimony, demonstrating that there was greater than 50% likelihood that the prescribed medical procedure produced the injuries. Klein v. Biscup, 673 N.E.2d 225, 232 (Ohio Ct. App. 1996). In order for Mr. Morton to successfully bring a lawsuit against our client, he must prove that disclosure of the risks in the mouse study was mandatory under law and that the islet cell transplant was the proximate cause of his injuries. It is unlikely that Mr. Morton will succeed in adducing such evidence and, as a result, our client will not be liable for performing a medical procedure without informed consent. Several cases in Ohio demonstrate how courts respond where patients have brought actions for informed consent. For example, in Nickell v.Gonzalez, 477 N.E.2d 1145, 1149 (Ohio 1985), the Ohio case credited with establishing the modern day test for informed consent, the court held that the patient gave her informed consent for a throat operation. In Nickell, the plaintiff saw her surgeon for a throat operation. Id. at 1147. After surgery, she was left with throat paralysis characterized as an “extraordinarily rare” occurrence. Id. at 1147-48. In finding consent sufficient, the court reasoned that a doctor was not obligated to anticipate every possible complication of an operation. Id. at 1148. The court additionally noted that it was unclear that the operation was the proximate cause of the paralysis. Id. at 1149. In addition, in Klein v. Biscup, 673 N.E.2d 225, 232 (Ohio Ct. App. 1996), a more recent Ohio Court of Appeals case, the court held that the defendant had sufficiently 3 disclosed material risks related to a performed spinal surgery. In Klein, the plaintiff underwent spinal fusion surgery to alleviate lower back pain. Id. at 227. The plaintiff had signed a consent form. Id. However, the defendant failed to reveal that he would be using bone plates and screws “off-label” (not according to FDA approval). Id. The surgery was unsuccessful, causing fractured vertebra, pain and incontinence in the plaintiff. Id. The court emphasized that the doctrine of informed consent in Ohio does not require a physician to specifically disclose the use of a medical material in a non-FDA approved manner. Id. at 231. Furthermore, the court noted that without expert medical testimony of a 50% likelihood of the spinal surgery producing the patient’s injuries, a material fact of proximate cause was not established. Id. at 232. In another Ohio case on informed consent, in Turner v. Children’s Hosp., Inc., 602 N.E.2d 423, 433 (Ohio Ct. App. 1991) the court held that a specialist at a hospital did not have a duty to inform other doctors that a child’s seizure disorder was related to adverse reactions to DPT vaccinations. In Turner, a child was administered DPT vaccinations by a series a physicians, leading to seizures and retardation. Id. at 426. A specialist at the hospital, overseeing the seizures exclusively, failed to note a connection between the DPT vaccinations and the seizures. Id. at 425. In finding adequate disclosure, the court reasoned that the specialist was not obligated to inform other doctors of material risks of which he was not aware and did not arise in his diagnosis. Id. at 433. Moreover, the court in Turner, noted that the specialist had not “proposed” the administration of the DPT vaccination. Id. at 431. The case law on informed consent in Ohio makes it clear that we will be able to assert a valid defense against the lawsuit brought by Mr. Morton. The baseline rule regarding informed consent in Ohio is that three elements must be met before a patient can bring an 4 action: (1) failure to disclose material risks, (2) the unrevealed risks were the proximate cause of injury and (3) a reasonable person would have elected not to undertake the procedure if the risks had been revealed. Nickell, 477 N.E.2d at 1148. As a further elucidation of the first element, doctors must reveal to patients reasonable material risks and benefits associated with the medical procedure. Congrove, 37 Ohio Misc. at 101. The legal rules governing disclosure of reasonable material risks do not extend revelation to every possible risk. In Nickell, the court held that “extraordinarily rare” risks do not need to be disclosed to a patient. 477 N.E.2d at 1148. It may similarly be argued that the renal failure risks can be construed as “extraordinarily rare” on the grounds that Sedgewick had no prior knowledge of the risk in mice or human subjects. The facts indicate that Sedgwick had no role in the mouse study and that renal failure only affected a small percentage of lab mice. This point of view is strengthened by the holding in Turner, in which the court held that doctors would not be held liable for failing to inform patients of risks that require going beyond basic medical duty, especially when more than one doctor is involved in the overall treatment. 602 N.E.2d at 433. Likewise, here, a court may find that Sedgewick should not be required to undertake additional research to discover such risks that were not medically apparent, especially given that she was not part of the initial study. Similar to Turner, it appears that the law in Ohio does not require doctors to consult extensively with previous physicians in order to determine potential risks. An argument could be made that this is especially true of a practitioner who implements a research protocol because she would not be in the position to know all of the nuances involved in the previous research. 5 Our position is further supported by the court in Klein, which emphasized that ‘offlabel use’ of a medical device, as part of a medical procedure, is not a material risk requiring disclosure. 673 N.E.2d. at 231. Analogous to Klein, it can be argued that the experimental treatment carried out on Morton was ‘off-label use’ since he was not of appropriate age for the study and therefore was not a designated research subject. As a result, our client may not have been required to disclose risks associated with the procedure, as its performance was ‘off-label’ and its corresponding risks were therefore not material according to Ohio law. We can sustain our defense more explicitly on the grounds that Sedgewick did not actually propose the treatment to Morton. In Turner, the court stated that the “duty to inform arises only when the physician in fact proposes some mode of treatment giving rise to a patient decision.” 602 N.E.2d at 431. The facts show that Sedgewick did not propose the treatment, but rather performed the treatment as a favor to Morton’s diabetes specialist, Dr. Parkinson, who actually recommended the experimental treatment. It can be asserted that Sedgewick’s role in Morton’s treatment was akin to that of a technician rather than the primary physician diagnosing, recommending and carrying out treatments for a patient. As such, Ohio law may not assign a duty to Sedgewick to reveal any material risks, let alone the results of the lab mice study. Alternatively, we may utilize another line of defense. The court in Nickell promulgated a three part rule for actionable failures to disclose appropriate medical risks. 477 N.E.2d at 1148. The rule specifically requires that unrevealed material risks “are the proximate cause of the injury in the patient.” Id. In the case at bar, given the temporal lag of eight months between the islet cell transplant and the injuries sustained by Morton, it can be argued that the medical procedure was not the proximate cause of the injuries. The facts 6 signify that Morton’s diabetes was under control following the procedure and it is more likely that an intervening cause was to blame for his renal failure. A defense by lack of proximate cause is further supported by the court’s decision in Klein. There, in order to meet the proximate cause rule, the court required the plaintiff to produce expert testimony of a 50% likelihood of the procedure being the cause of the injuries sustained. Klein, 673 N.E.2d at 232. In the case at bar, the mortality rate in the mouse study was merely 7% and not all deaths were attributable to renal failure. Given these facts, and that renal failure is not an uncommon consequence of uncontrollable diabetes, Denise Grady, A Diabetes Treatment Fails to Live Up to Early Promise, N.Y. Times, Sept. 28, 2006 at A16, there is a strong likelihood that the renal failure will not be attributed, at 50% likelihood, to the experimental treatment carried out by our client. Consequently, having not satisfied all three criteria promulgated in Nickell, our client is not liable for the tort of lack of informed consent. However, Morton’s counsel may proffer a number of counterarguments that Morton did not give informed consent to the treatment. For example, in Nickell the court applied the reasonable patient standard. 477 N.E.2d at 1149. Morton may argue that a reasonable patient would have assigned significant risk to the information withheld by our client regarding mortality in mice. A risk that upon incidence inherently results in death, regardless of the likelihood, would likely be of import to a patient. Thus, Dr. Sedgewick should have informed him of any information that may have influenced his decision to assent to the procedure. Additionally, in Turner, the court stated that patients must be informed of all risks that a “reasonably prudent physician would disclose.” 602 N.E.2d at 432. Morton may also argue that Sedgewick failed to inform herself prudently of serious and reasonable risks 7 associated with the procedure and, thus carelessly failed to disclose reasonable risks to Morton. To further counter our defenses, Morton may distinguish the facts in the case at bar from those in Nickell. In Nickell, a physician was not required to disclose “extraordinarily rare” risk of paralysis. 477 N.E.2d at 1148. Morton may assert that the mortality risk among mice in the collateral mouse study could not be construed as “extraordinarily rare.” A seven percent mortality rate, where one in every fourteen mice died as a result of the treatment, may be more readily classified as a probable risk than an “extraordinarily rare” occurrence. Consequently, Sedgewick had a legal duty to disclose the results of the mouse study to Morton. Even with the arguments presented by opposing counsel, we still have a strong position and can counter their arguments. The courts have held that a doctor is not required to inform a patient of all risks. Turner, 602 N.E.2d at 431; see also O’Brien v. Angley, 407 N.E.2d 490, 495 (Ohio 1981). As mentioned above, this disencumbers the physician of the duty to disclose material risks, specifically where the medical procedure is ‘off-label.’ Klein, 673 N.E.2d. at 231. It also likely protects the physician from undertaking onerous additional research. Turner, 602 N.E.2d at 433. While our client may have had an ethical imperative to investigate deeply into the risks associated with his research, she is likely only legally bound to inform the patient of such risks as a reasonable physician would be aware. CONCLUSION As a rule of law in Ohio, informed consent requires a physician to reveal relevant and reasonable risks associated with a particular medical procedure. Congrove, 37 Ohio Misc. at 101. Failure to fulfill this requirement, however, is not actionable as a tort unless there was 8 an injury and a reasonable sense that the injured party would not have consented to the procedure had the relevant risks been revealed. Nickell, 477 N.E.2d at 1148. In the case at bar, our client was not legally bound to disclose the result of the mouse study. Dr. Sedgewick was not aware of the mouse mortality data and is not legally required to disclose material risks of which she is not cognizant. Even if Dr. Sedgewick had known the risks, she would not have been required to disclose them since she was performing the medical procedure ‘off-label,’ on an individual not involved in the actual study. Additionally, is it unlikely that Morton will be able to prove the islet cell transplant as the proximate cause of his injuries. Therefore, in the case at bar, we should be able to defend our client from the action brought by the plaintiff. 9