cpinmemo

advertisement

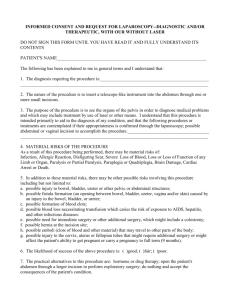

MEMORANDUM TO: Karin Mika FROM: 1633 DATE: October 23, 2006 RE: Informed Consent Memo ISSUE WHETHER A PHYSICIAN THAT PERFORMED A PHASE I EXPERIMENTAL MEDICAL PROCEDURE ON A PATIENT IS LIKELY TO SUCCEED IN DEFENDING A LACK OF INFORMED CONSENT ACTION WHEN THE PATIENT SIGNED STANDARD MEDICAL CONSENT FORMS AND THE PHYSICIAN WAS NOT AWARE OF ALL POSSIBLE RISKS AND DANGERS OF THE PROCEDURE. STATEMENT OF FACTS The plaintiff, Jared Morton (hereinafter Morton), is a 37 year old male who has suffered from Type 1 diabetes for a majority of his life. Morton administered insulin daily to control his condition. In 2003, Morton’s diabetes became progressively harder to control. At this time, he asked his physician, Dr. Edgis Parkinson, a diabetes specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, whether there were any other treatments available. Dr. Parkinson suggested that Morton consider what was then an experimental treatment of an islet cell transplant and put him into contact with another physician. Dr. Parkinson set up an appointment for Morton with Dr. Arliss Sedgewick, the defendant and our client, (hereinafter Dr. Sedgewick), at University Hospitals Diabetes Clinic in Cincinnati. Dr. Sedgewick explained to Morton that he was over the age to be included in a Phase I experimental study, but as a favor to Dr. Parkinson, would arrange for treatment if Morton wished. Prior to undergoing the procedure, Morton was given numerous standard medical 2 consent forms agreeing to undergo treatment, accepting the risks and side effects associated with the treatment, and abiding by the judgment of the physicians associated with the Diabetes Clinic. Furthermore, Dr. Sedgewick explained that the experimental procedure appeared to provide the only hope for control of Morton’s Type 1 diabetes. Side effects, other than those mentioned in the standard medical consent forms Morton signed, were not discussed. Morton did, however, ask Dr. Sedgewick what she would do in his position and her response was, “If it were me, I would go ahead with the procedure.” Morton was not provided with documentation concerning the Phase I Study due to its length and complexity. The Phase I documentation stated that success and side effects were not entirely known, and reported that there was a 7% mortality rate in lab mice undergoing the treatment, with the majority succumbing to kidney failure. The islet cell transplant procedure was performed in November of 2004. Within six months, Morton’s diabetes seemed to be under control, but by the seventh month, Morton’s diabetes returned. During the eighth month following the transplant, Morton’s kidney functions began to diminish to the point that within a year of the procedure Morton learned he would require a kidney transplant. Morton is currently on the transplant list, and undergoes dialysis three times a week. Morton filed suit in Spring 2006 against defendant and our client, Dr. Sedgewick, and the University Hospitals Diabetes Clinic alleging medical malpractice and battery on the theory that he did not give informed consent to having the islet cell transplant. Dr. Sedgewick stated that at the time of the procedure, “there was no way of knowing that Morton would have gone into kidney failure.” She further stated that she was unfamiliar 3 with the work of early researchers who feared side effects related to kidney damage, and that she was not an expert in the complete text of the Phase I packet of information. DISCUSSION The general rule in Ohio regarding informed consent is that, prior to performing any type of medical procedure upon a patient, a physician has a legal duty to inform a patient of the nature of the procedure, the risks and dangers of the procedure, and the expected benefits of the procedure. Congrove v. Holmes, 37 Ohio Misc. 95, 101 (Ct. Com. Pl. 1973). Courts have held that the risks and dangers a physician must inform his patient of need not be exhaustive. O’Brien v. Angley, 407 N.E.2d 490, 495 (Ohio 1980). Rather, the physician has a legal duty to inform of “material risks and dangers.” Nickell v. Gonzalez, 477 N.E.2d 1145, 1148 (Ohio 1985). Here, Dr. Sedgewick had the legal duty to inform Morton of the “material risks and dangers” of the islet cell transplant. Id. The facts reveal that at the time the procedure was performed, side effects were not entirely known and kidney failure was not established by the medical community to be one of the “material risks and dangers” of the islet cell transplant. Id. Therefore, it is likely that Dr. Sedgewick will be able to successfully defend the suit brought by Morton because at the time the procedure was performed, she had no legal duty to inform Morton of possible kidney failure because it was not known or established to be one of the “material risks and dangers” of the procedure. Id. There are several cases that discusss the doctrine of informed consent in Ohio. In Congrove v. Holmes, the court held that a patient’s consent to a throat operation was not “informed.” 37 Ohio Misc. at 101-06. In this case, defendant, physician, performed 4 a bi-lateral thyroidectomy on plaintiff, patient. Id. at 97. Defendant did not inform plaintiff of the risks or dangers, paralysis of vocal cords, that were associated with the procedure. Id. After performing the procedure, plaintiff’s vocal cords were permanently paralyzed. Id. In finding for the plaintiff, the court reasoned that “informed” consent requires that a patient understand all reasonable risks of a surgery. Id. The court then noted that paralysis of the vocal cords was definitely a reasonable risk of the throat surgery and that the plaintiff should have been made aware of the risk before the surgery occurred. Id. at 104. In another case, O’Brien v. Angley, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that a the consent of the patient was “informed,” even though not all risks of the procedure were disclosed. 407 N.E.2d at 495. In this case, defendant, physician, administered a drug, Garamycin, to plaintiff, patient. Id. at 491. Defendant’s decision to administer the drug, above recommended dosage, resulted in plaintiff’s hearing loss. Id. at 492. Defendant never informed plaintiff of the risks and dangers of hearing loss associated with the use of Garamycin in excess of recommended dosage. Id. In finding the consent was “informed,” the Supreme Court of Ohio reasoned that a physician need not inform a patient of all possible risks of a treatment. Id. The court noted that there were some instances where a physician’s discretion in how to conduct treatment should not be penalized. Id. In another case, Nickell v. Gonzalez, the Supreme Court of Ohio set out specific elements that should be weighed when determining whether there is a lack of informed consent. The court stated, “The tort of lack of informed consent is established when: 5 (a) The physician fails to disclose to the patient and discuss the material risks and dangers inherently and potentially involved with respect to the proposed therapy, if any; (b) the unrevealed risks and dangers should have been disclosed by the physician actually materialize and are the proximate cause of the injury to the patient; and (c) a reasonable person in the position of the patient would have decided against the therapy had the material risks and dangers inherent and incidental to treatment been disclosed to him or her prior to the therapy.” 477 N.E.2d at 1148. In this case, defendant, physician, performed a thoracic outlet syndrome operation on plaintiff, patient. Id. at 1147. As a result of the procedure, plaintiff had a condition known as brachial plexus palsy: a paralysis of nerves in the neck and armpit, that extend throughout the arm. Id. Defendant did inform plaintiff of commonly known risks and dangers of the procedure, but plaintiff filed suit on the ground that defendant did not “adequately” disclose the risks. Id. In finding for the defendant, the court reasoned that, although the specific risk of the injury was not disclosed to the patient, the injury was a rare complication. Id. at 1149. The court concluded that it was a physician’s obligation to disclose only “material risks and dangers.” Id. at 1148. Based on the cases decided in Ohio regarding informed consent, it seems likely that Dr. Sedgewick will be able to successfully defend the suit brought by Morton. When proving that there was a lack of informed consent, the plaintiff must prove that he/she was not told the material risks of an operation. Id. Not every risk need be told to a patient, especially those risks that are rare. Id. Congrove and O’Brien both provide precedent that will be beneficial to Dr. Sedgewick. In Congrove, the court held that a physician has a legal duty to inform a patient of the “reasonable risks and dangers of a procedure. Congrove, 37 Ohio Misc. at 6 101. However, in O’Brien, the court narrowed the holding of Congrove by holding that a physician does not have to “fully inform” a patient of all risks and dangers of a procedure, especially those that involve discretion in treatment. O’Brien, 407 N.E.2d at 495. Here, Dr. Sedgewick provided Morton with standard medical consent forms that set out the reasonable risks of the procedure. Morton was aware of the fact that this procedure was part of a Phase I study and experimental in nature. Because this was an experimental procedure and the risks and dangers were not entirely known, Morton’s signed standard medical consent forms appear to evidence that he accepted the reasonable risks. It follows that Dr. Sedgewick had no legal duty to “fully inform” Morton of risks and dangers that were not entirely known or established to be risks and dangers at the time of the procedure. Id. The rationale from Nickell also provides support for Dr. Sedgewick’s position. In Nickell, the court held that the most important element of demonstrating a lack of informed consent was demonstrating that a doctor did not disclose a material risk of a procedure. 477 N.E.2d at 1148. In defining “material risk,” the court stated that, “a risk is material when a reasonable person, in what the physician knows or should know to be the patient’s condition, would be likely to attach significance to the risk or cluster of risks in deciding whether or not to forego the proposed treatment.” Id. at 1149. Here, Dr. Sedgewick had the duty to inform Morton of the “material risks and dangers” of the procedure. Id. at 1148. The facts reveal that side effects were not entirely known and that kidney failure was not established to be one of the “material risks and dangers” at the time of the procedure. Id. Because kidney failure was not entirely known or established 7 to be one of the “material risks and dangers” of the procedure, it could be argued that Dr. Sedgewick had no legal duty to inform Morton of such risks. Id. Morton may present various responses to our position. For instance, Morton might argue that only the holdings of Congrove and Nickell are applicable here because O’Brien can be distinguished on its facts. In O’Brien, the issue of informed consent was secondary to the plaintiff’s request for a specific jury instruction. 407 N.E.2d at 495. (Plaintiff sought a jury instruction stating that a medical practitioner must, prior to performing a procedure, “fully inform” his patient of risks and dangers of the procedure.) Id. Morton may argue, with some success, that O’Brien’s holding on informed consent is taken out of context because the case hinges on evidence and a jury instruction; the issue of informed consent is merely a secondary issue. Morton may allege other arguments based on Congrove and Nickell. In Congrove, the court stated in dicta that a physician has a legal duty to inform a patient of the nature of a procedure, the risks and dangers of the procedure, and the expected benefits of the procedure. Congrove, 37 Ohio Misc. at 101. In Nickell, the court foused on a “discussion” of “material risks and dangers” of the procedure. 477 N.E.2d at 1148. Here, Morton can argue that Dr. Sedgwick never discussed the benefits of the procedure nor did she have any protracted discussion about the risks. Morton’s position, however, is unlikely to succeed. Nickell sets out that a physician has a legal duty to inform a patient of “material risks and dangers” associated with a procedure. Id. The fact is that, at the time of the procedure, kidney failure was not entirely known or established to be one of the “material risks and dangers” of the 8 procedure, therefore, Dr. Sedgewick will be able to successfully defend the suit brought by Morton. Id. CONCLUSION The general rule in Ohio regarding informed consent is that a physician, prior to performing any type of medical procedure on a patient, has a legal duty to inform a patient of the “material risks and dangers” of a procedure Here, it should be argued that Dr. Sedgewick had no legal duty to inform Morton of possible kidney failure because it was not entirely known or established to be one of the “material risks and dangers” of the islet cell transplant at the time the procedure was performed. Rather, Dr. Sedgewick’s only legally required course of action in informing Morton, and the action that she took, was to provide Morton with standard medical consent forms agreeing to undergo treatment at the judgment of his physicians. In response, Morton may argue that Dr. Sedgewick never discussed kidney failure as being one of the risks and dangers of the procedure and had a legal duty to do so, but this argument will not satisfy element “(a)” of the three elements necessary to prove the tort of lack of informed consent. Therefore, it is likely that defendant and our client, Dr. Sedgewick, will be able to successfully defend the suit brought by Morton.