TonyMoore - WasteMINZ

advertisement

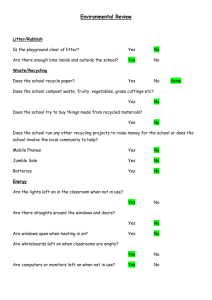

WASTER PAYS – ONE YEAR ON IN CHRISTCHURCH Tony Moore, Senior Planner, Christchurch City Council tony.moore@ccc.govt.nz, 0064 (3) 941 6426 Abstract Direct charging for waste disposal is a core policy contained in the New Zealand Waste Strategy and in the waste plans of Councils throughout the Country. However, its implementation and effectiveness can be clouded. Applying direct charges to domestic refuse collection can result in concerns about higher levels of contamination in kerbside recycling, illegal dumping and a mass exodus from Council, to private, waste collection services. Likewise, “pay as you throw” systems for domestic refuse collection are often established along with improvements to kerbside recycling services, making impacts of the financial disincentive difficult to determine. In April 2004 the Christchurch City Council went part-way to a full direct charging regime for domestic refuse collection. It halved the number of 50 litre, rate-funded rubbish bags allocated to each property to 26 bags per year and lowered the annual rates demand accordingly. This change was made without altering other waste or recycling services, making it possible to isolate the impact of moving towards direct charging in the city. After the first year, the tonnes collected in rubbish bags fell by 10% resulting in a $620,000 saving to the community in waste collection and disposal costs. The tonnes recycled at the kerbside increased by 16% and contamination and illegal dumping remained at background levels. Ten percent of households decided to use a private waste collector, largely due to an aggressive promotional campaign by the collectors and public uncertainty about the changes. The total number of rubbish bags used in Christchurch fell by 34% indicating that households were using bags leftover from previous allocations, placed more into each bag (average bag weight increased by 1 kg per bag) and moved to use private collection services. This paper concludes that moving, even part way, toward direct charging for domestic refuse collection is an effective way to encourage waste minimisation, provided dumping in roadside litter bins and the impact of private waste collectors are managed. However, greater waste avoidance is achieved by combining direct charging with an increased opportunity to recycle at the kerbside. Introduction This paper provides a case study on the impact of direct charging for domestic refuse collection in Christchurch. It is particularly relevant to policy and decision makers wanting to implement polluter/waster pays policies for domestic refuse collection and for those with an interest in the impact and effectiveness of such policies. Full cost pricing for refuse disposal is a core principal contained in the New Zealand Waste Strategy (MFE 2002). “Efficient pricing policies that as far as practicable reflect the full cost of waste disposal … are the cornerstone of this strategy.” Full cost pricing policies have been adopted, at least in principle, by most Councils in New Zealand. However, implementing polluter/waster pays policy in relation to kerbside refuse collection in New Zealand can be problematic. It is fundamentally a political decision that can be hotly debated, fuelled by fears of illegal dumping, increased contamination of existing recycling services, unfair impacts on lower-socioeconomic groups and uncertainty about shifts from Council, to private, waste collection services. This situation is compounded by an apparent lack of clear evidence that such policy will actually reduce waste. Case studies investigating the impact of direct charging for refuse collection are not clear because many also include the introduction of, or improvements to kerbside recycling services. Waste reductions of between 20 – 60% were achieved when direct charging was introduced along with kerbside recycling or organic collection services (Skumatz 2002). The benefits directly attributable to the economic disincentive to dispose of refuse are clouded with the increased opportunity to reduce waste. A study of 500 communities in North America that aimed to isolate the impact of direct charging for kerbside services found that refuse disposal fell 17% by weight, with 10% being attributable to increases in kerbside recycling and 6% to source reduction (Skumatz 2002). But this study failed to include the impacts of illegal dumping and shifts to private waste collection services. Other studies have looked specifically at the issue of illegal dumping and found that only short-term problems arose that were readily dealt with by education and enforcement (Skumatz 1994). However, such observations are likely to be specific to the community and would reflect such things as the culture and community norms, the background level of illegal dumping and enforcement, and the availability of sites for dumping refuse in and around the city. To assist decision makers in New Zealand, local evidence is needed that can isolate the impact of direct charging for domestic refuse collection and that addresses the impacts of illegal dumping and private waste collection services. In April 2004 the Christchurch City Council went part-way to a full direct charging regime for domestic refuse collection. It halved the number of 50 litre, rate-funded rubbish bags allocated to each property to 26 bags per year and lowered the annual rates demand accordingly (people that required more rubbish bags were able to buy them for $1.10 per bag at supermarkets and Council service centres). This change was made without altering other waste or recycling services, making it possible to isolate the impact of moving towards direct charging in the City. Key Findings – One Year On It would be premature to judge the effectiveness of the 26 rubbish bag decision on the first year of the scheme. The full effect of the bag reduction has yet to occur for the following reasons: People need time to adjust to the new system and to find their own solutions to minimise waste. After one year many households were still using rubbish bags left over from previous allocations. Future improvements to kerbside services are proposed including the introduction of wheeliebins for the collection of recyclables and organics (e.g. food scraps and greenwaste). An anticipated shift to private waste collection services occurred due to the providers carrying out aggressive promotion campaigns and due to public uncertainty about the changes. National and international experience would suggest that at least some of these households would revert back to the Council services once things settle down and as the price for these private services increases with the disposal of waste to a new regional landfill at Kate Valley in June 2005 ($125/tonne). Please note that Christchurch is a city of 135,000 households and 340,000 residents and where refuse and recyclables are collected each week at the kerbside. Despite these constraints the following observations could be made about the period from 1 May 2004 to 30 April 2005: a) The cost of providing 26 rubbish bags per year to each property came off the rates, meaning that the Christchurch rates are now 1.2% lower than they would have been with a 52 rubbish bag allocation. b) A 16% (3,800 tonne) increase in the total amount collected in green kerbside recycling crates (Figure 1), with contamination remaining at previous background levels (below 2% by weight). Participation in kerbside recycling remained high, at around 90%, but the amount set out in the 45 litre green recycling crate increased to 3.4 kilograms per household per week. c) A 10% (3,360 tonne) reduction in the total amount of waste collected in black rubbish bags (Figure 1). This waste reduction equates to a saving for the community of nearly $620,000 (at $187 per tonne to collect and dispose of the rubbish bags). The weight of individual rubbish bags rose from an average of 4.6 kg to 5.5 kg per bag. Therefore, people were fitting more into each bag, but throwing out less household rubbish overall. Refuse collection in the Council rubbish bags now stands at 4.5 kilograms per household per week. It is important to place this achievement in context, because over the same time the total amount of waste landfilled increased by 12%, largely due to the buoyant economy. The amount collected in rubbish bags could have increased accordingly. The fact that it fell, and that kerbside recycling increased, indicates the success of the scheme. Figure 1. Amount Collected at the Kerbside by the City Council (Tonnes 1,000) 50 45 Move to 26 Rubbish Bags Black Rubbish Bag 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 Green Crate Kerbside Recycling 5 0 1994/95 1995/96 1996/97 1997/88 1998/99 1999/00 2000/01 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 2004/05 Year ending 30th June d) A 34% reduction in the number of rubbish bags acquired by residents from the Council compared to the same period in the previous year (i.e. 2,900,000 fewer bags were either purchased or allocated to residents by the coupon system in 2004/05 than in 2003/04). Indicating, that people are making do with fewer bags or are using bags left over from previous allocations. e) Based on surveys, a 10% increase in the use of private waste collection services occurred largely due to waste companies undertaking aggressive promotional campaigns and public uncertainty around the decision. Anecdotally, this shift would have been reduced had the Council improved the kerbside recycling services at the same time as reducing the allocation of rubbish bags. A rubbish bag in Christchurch on average contains 50% organic matter and 20% recyclables by weight. The option of introducing an organics collection service, together with an expansion of the items able to be recycled, would have given residents greater opportunity to minimise waste and so reduced the attractiveness of privately provided wheeliebins (less incentive is created to compost or recycle when a household is presented with and compelled to fill a 240 litre waste bin each week). f) Illegal dumping or “fly tipping” in the City has remained at background levels (e.g. 12 reported cases via Requests For Service per week including dumping in parks, waterways and other areas, but excluding abandoned cars). Observations in Christchurch over the last 5 years indicate that illegal dumping is more closely linked to tipping fees at Refuse Stations, the availability of free drop-off points for reusable or recyclable items (e.g. for unwanted white-ware and old furniture) and charges for greenwaste composting. The most common items inappropriately disposed of are garden waste (offenders may think this will simply disappear and is not actually dumping, but dispersed composting), larger household items of furniture or appliances and rubble and demolition material. All of which are unrelated to the unit cost of a rubbish bag (these items are difficult to put into a 50 litre rubbish bag). g) The amount of household rubbish collected in roadside litter bins increased 15% above long-term trends (Figure 2). Roadside litter bins were an easy target for residents and because the Council has a regular emptying regime, it effectively provides a free household waste disposal service to nearby residents. A programme to manage this issue was implemented during the year, including placing stickers on the roadside litter bins and ongoing enforcement (including the identification of offenders and the issue of fines). Figure 2. Tonnes 350 Monthly Tonnage Collected From Roadside Litter Bins Allocation of 26 rubbish bags 300 250 200 Long-term trend 150 100 50 Month Jun-05 Apr-05 Feb-05 Dec-04 Oct-04 Aug-04 Jun-04 Apr-04 Feb-04 Dec-03 Oct-03 Aug-03 Jun-03 Apr-03 Feb-03 Dec-02 Oct-02 Aug-02 Jun-02 Apr-02 Feb-02 Dec-01 Oct-01 Aug-01 0 h) An average of 1.4% of households were initially using non-Council bags to dispose of their household rubbish. An initial situation arose where some residents mistakenly purchased and used non-Council rubbish bags. These bags were not collected and marked with rejection stickers, in-line with normal practises. Where this mistake was made consistently, notices were placed in letterboxes to inform residents of the correct way to dispose of household refuse. This issue then returned to background levels (below 0.3% of households). Council took a firm line on the use of non-Council rubbish bags, which contributed to an average of 13 telephone calls per week asking for the Council to remove non-Council bags. (Note: only official Council bags, those clearly marked with the Council logo, were collected because the bag price includes the cost of collecting and disposing of the rubbish). Conclusions In spite of an initial reluctance from the public, Council staff have received relatively few complaints and in some instances letters in support of the decision have been received. Anecdotally, public opinion remains polarised on the issue. Experience from elsewhere indicates that after an initial resistance, people accept direct charging for refuse disposal (“pay as you throw” systems) and see them as a fair way to pay for waste disposal services and to minimise waste. In Christchurch, even moving part-way to a direct charging system for kerbside refuse collection has resulted in waste minimisation benefits. The 10% reduction in refuse collected in rubbish bags and the 16% increase in kerbside recycling are in line with experiences elsewhere and could be replicated by others. Should the Council consider a reduction of the remaining 26 rate-funded rubbish bags it would be prudent to also increase the opportunities to recycle to avoid further “leakage” to private collection services and to litter bins. Increasing the opportunities for residents to reduce waste, through improvements to kerbside recycling services, would provide a balanced carrot and stick approach, which is generally more attractive to the public and effective at reducing waste. It would be no understatement to say that the implementation of “waster pays” in Christchurch would have been made much easier if an improved recycling service was offered to the public at the same time as the bag reduction. Confusion through the public debate and negative reactions to the Council’s decision were likely to have resulted in a greater shift to private collections and the use of litter bins for household waste. Consequently, this paper concludes that moving, even part way, toward direct charging for domestic refuse collection is an effective way to encourage waste minimisation, provided dumping in roadside litter bins and the impact of private waste collectors are managed. However, greater waste avoidance and perhaps public acceptance, would be achieved by combining direct charging with an increased opportunity to recycle at the kerbside. References MFE (2002) The New Zealand Waste Strategy: Towards zero waste and a sustainable New Zealand. Ministry for the Environment, Wellington, New Zealand. Skumatz, A., et al (1994) Illegal dumping: incidence, drivers and strategies. Research paper 9431-1, Skumatz Economic Research Associates Inc., Seattle. Skumatz, A. (2002) Variable-rate or “pay as you throw” waste management: answers to frequently asked questions. Reason Public Policy Institute, Reason Foundation, Los Angeles.