Kanji Lookup

advertisement

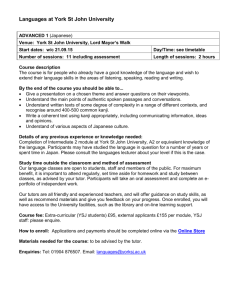

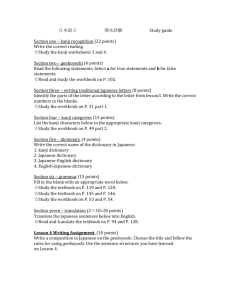

Kanji[AU: this title is broad enough to be about all things kanji. Perhaps “An Beginning Learner’s Introduction to”?] Kanji is the character based writing system imported to Japan from China. Often erroneously referred to as pictographs, kanji incorporate not just pictographic but also ideographic, phonetic, and semantic concepts. Because the readings (pronunciations) of the kanji were adopted along with their meanings, they have introduced countless Chinese-based terms into Japanese.[AU: give readers some sene of what you’ll be covering and your purpose in that. Is it to ease beginning kanji learners into its study? If so, indicate that too.] Origin and Evolution [AU: I recommend adding “of Kanji” to ensure clarity, distinction from the historical categories section] Until the 5th century, the Japanese language was purely oral, with no written equivalent. It is commonly accepted that kanji (the word itself being the Japanese pronunciation of hanzi, or "Han letters," a reference to the Han Dynasty) were brought to Japan by Buddhist monks in the form of Chinese texts. These texts were initially read as-is, but over time a system called kanbun was introduced wherein key concepts were notated by a series of marks, allowing them to be read according to Japanese grammar. Eventually, simplification of the kanji led to the independent creation of the hiragana and katakana syllabaries, which were used in conjunction with the kanji to represent the multiple inflections possible in Japanese grammar. As the writing system stabilized, the pronunciations afforded any given kanji fell into four basic categories: Kun-yomi. The native Japanese word that existed prior to the introduction of the kanji is preserved in the kun-yomi, or "native reading." The kun-yomi of is shita, meaning "down." Kanji are not limited to a single kun-yomi: an alternate kun-yomi of is shimo, as in (kawashimo, "downriver"). On-yomi. The pronunciation imported along with the kanji itself is called the onyomi, or "Chinese reading." The on-yomi of is KA, as in (karyō, "subordinates.") Because kanji were often reintroduced over multiple time periods and from different dialects of Chinese kanji tend to have several different on-yomi. , for example, can also be read GE, as in (gezai, "laxative.") (When rendering kun- and on-yomi into Roman letters, the linguistic standard is to have kun-yomi in lowercase and on-yomi in uppercase.) Jinmei-yō. Those characters specifically set aside for use in names are called jinmei-yō kanji, or "name characters." The jinmei-yō reading is often an older or obsolete pronunciation of the kanji: , for example, has the kun-yomi of atsui ("thick") but a jinmei-yo pronunciation of Atsushi, a variant reading that is now a common male name. Ateji. Kanji that are used for their meaning, regardless of pronunciation -- or vice versa -- are referred to as ateji, or "substitute characters." While ateji continue to be used in Chinese, their usage in Japanese has declined following the introduction of the kana syllabries, which allow for the ready introduction of foreign or linguistically incompatible concepts. Figure 1. "America" in ateji chosen for sound rather than meaning, and ichijiku ("fig") in ateji for meaning ("no flower fruit") rather than sound. Kanji Lookup Kanji can be found in dictionaries by one of four lookup methods: on-yomi and kun-yomi, (which have already been discussed), and bushu and kaku.[your preceding discussion of the first two does not address the look-up part. Why not bring them in here; I doubt readers will sense any repetition! Also, a bit more procedue here would help: for example, “When you look up a kanji word(?), you have to decide which method to use….” Or some such. And maybe explain how one chooses from these methods—in no great detail, please, but just a hint. ] Bushu. Referred to as “radicals” in linguistic terminology, bushu are considered the core element of the kanji in terms of categorization.[AU: what are the categories] When looking up the character (numa, or swamp), for example, one would look under its bushu , called sanzui. Traditionally, there are 214 bushu, though some modern kanji scholars have attempted to reorder the kanji to significantly reduce this number.[AU: I don’t think your intended readers will have a clue as to the meaning of this.] Kaku. The total number of strokes it takes to write a kanji is called its kaku. Looking for a kanji by its kaku requires a thorough knowledge of how strokes are counted, as well as the order in which they are drawn. The character (on-yomi soto, "outside") contains 5 strokes, each written in a specific order. Figure 2. Stroke order for kanji soto. Historical Categories[AU: since this discussion refers to events before the arrival of hanzi to Japan shouldn’t it come before the preceding evolution section?] [also, consider adding “of Hanzi” to prevent readers from thinking this section is about kanji] [AU: maybe some clarifying transition here “Before its arrival in Japan in the 5th century AD, hanzi was categorized into…”] Around the second century A.D., the Chinese scholar Xu Shen classified categorized the hanzi into six groups categories that remain in use to this day for both hanzi and kanji.[AU: to classify means locating an item into a category] Shōkei moji. A stylized picture of a physical object. Yama, meaning "mountain" is written and is modeled after the shape of a mountain. Shiji moji. A representation of an abstract concept. Ue, meaning "up," is written and represents one line above another with a third line connecting. Kai'i moji. The ideograph, often made by combining two or more shokei or shiji moji. Tōge, meaning "mountain pass," is written and is a composition of the characters , , and .[AU: I can see how the first two characters apply, but what’s the 3rd?] Keisei moji. The largest of all groups, kaisei moji are the deliberate pairing of a phonetic and ideographic element to create a new kanji. For example, (unaji, "nape") combines the ideographic , which originally meant "head" but in modern Japanese means "page," with the phonetic element ("craft"), chosen as a simplification of ("behind" or "rear") based on similarities in appearance and pronunciation (both have the on-yomi of KŌ) -- thus, means "rear of the head," or nape, and takes its on-yomi KŌ from its phonetic element, .[AU: for beginning learners and for this intro, I think you could simply: maybe not mention the “craft” and “page” part at all—but without harming the accuracy. The main point is elements meanig “head” and “rear” combine to mean “nape.”] Tenchū moji. When characters, whether mistakenly or by association, take on extended meanings and readings, they are referred to as tenchū moji. An example would be , which originally meant "nail" but was so often borrowed to represent the concepts of "(city) block" and "exact" that it has taken on those meanings exclusively. ("Nail" is now represented by , which adds the component , meaning "metal").[AU: this example raher eludes me: how could “nail” ever become asociated with “city block”? Better example possibly?] Kasha moji. Technically a method of usage than a class of characters, kasha moji are those characters used to create ateji readings.[AU: define?] In modern Japanese, a truncated form of kasha moji is often used in newspapers to refer to foreign countries: (do(ku)itsu) and (furansu) were once the accepted renderings of Germany and France, respectively, but the modern Japanese press prefers the shortened forms of and .[A: once gain, I think you could cut the rest of the sentence starting at “but” and point out how doit-“ sounds a bit like deutsche (as in Deutschland) and “furan” sounds a bit like France] [AU: this is fascinating reading only after several attempts. Interesting to see how characters for different words combine to create new meanings. I hope that my suggestions will help make this intro more accessible to beginning kanji learners.]