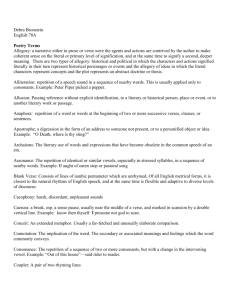

A POSTERIORI: In rhetoric, logic, and philosophy, a belief or

advertisement