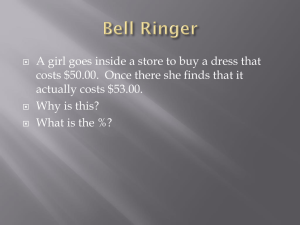

Benjamin + William Frankling POV + Summarizing

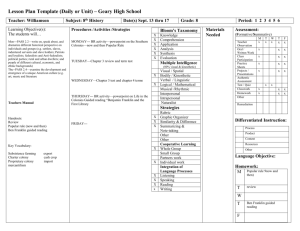

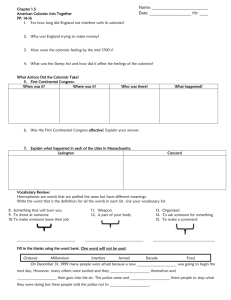

advertisement

Benjamin & William Franklin – Patriot & Loyalist: Two Sides of the Same Coin Goals: Understand the differing viewpoints of Patriots and Loyalists and understand that it’s not necessarily about right versus wrong. Practice reading of informational text Practice summarizing skills Materials: Handout of a review of Sheila Skemp’s book about Benjamin and William Franklin From Historical Spotlight website - document printed in two-column format Sticky Notes Larger pieces of paper for display of sticky notes Process: Students assigned or select working partner Each student reads paragraph one, underlining or making margin notes Student pairs discuss the paragraph and write a summary on the handout Review process / results with class Students work through the remaining 9 paragraphs of the paper Read/ Share with partner/ summarize and Repeat When finished students combine pairs into groups of four and compare summaries Discuss summaries as a class Students go back to original partners and together they write tweets for each of the paragraphs. They should be able to write one Tweet for each paragraph, (Paragraph 2 might be an exception where two Tweets are written – see sample Tweets) Students write Tweets on sticky notes (one note per Tweet) and place Tweets in chronological order on larger sheet of paper. When all Tweets are done, students do Chalk Talk activity, walking around room and reading other groups’ Tweets. As they walk around, they can leave mini-Tweets on papers (70 characters or less) Tweet: 140 characters including spaces, punctuation, symbols Students may use abbreviations/word substitutions such as 2 for to, too and 4 for for, fore Other abbreviations may be used as appropriate as long as the Tweet can still be read and understood by the average person (or me!) See Sample Tweets Sample Tweets Paragraph 1. B+W Franklin both patriots w/different POV about govt + its role 2. Loyalist: Colonists r anarchists – out of control Patriot: Parliament is tyrant – no more taxes Loyalist: Govt necessary to protect rights Patriot: M/rebel to protect rights 3. WF = Empire B4 colonies – Whole B4 parts 4. Wm says we need Eng+law/order ok 2 criticize govt but whole more important than parts 5. Wm says col = anarchy govt keeps order c/lose rights w/independence 6. Wm says stability over anarchy wants colonies to survive 7. Ben w/n/b anarchy w/indep -we must stand up 4 rights to keep them 8. Amer colon b/c more important w/b more powerful King ok Parliament not 9. 1st settlers say w/obey but descendents d/not -can say no if things change 10. not about right/wrong both want good but times + circumstances change The following reading references a book about Benjamin and William Franklin and their differing opinions as to whether or not the Thirteen Colonies should declare independence from Great Britain. They were certainly not the only two who disagreed; some historians believe that as many as one-third of colonists sided with William and another third with Franklin. Read each section of the article by yourself, highlighting or making margin notes as you feel needed. Then, working with a partner, use the column on the left to summarize each paragraph. As much as possible your summary should be in your own words and it should include the main idea of the paragraph, You will notice there is not much space to write, so make sure you focus on the main ideas. Both partners should write the summary on their papers. 1 Author Sheila L. Skemp’s book Benjamin and William Franklin attempts to disprove the opinion that because Loyalists and Patriots during the Revolutionary War had divergent political views, they can simply be categorized into two distinct parties: “good guys and bad guys.” Using the accounts of Benjamin Franklin (a Patriot) and William Franklin (a Loyalist), Skemp’s thesis demonstrates how the distinction between the two parties was not so black and white. Both men wanted what was best for the colonies. It was their different perspectives of government, not their values, which collided. 2 The British government operated under a ‘checks and balances’ type system. Power was divided between the House of Commons, the House of Lords, and the Crown. If one of these sections of government attempted to encroach on another’s powers, colonists believed that either anarchy or tyranny would result. Thus, the Patriots saw parliament’s meddling in colonial affairs as tyrannous, but Loyalists saw the colonial assemblies’ desire for more authority as anarchical. Further, all colonists would have agreed that they possessed the rights of Englishmen. Yet, while Patriots would have argued that such rights could only be protected by rebelling against Britain, Loyalists stated that such rights would be threatened without a proper government to protect them. 3 Prior to the War, however, all colonists shared an integral belief – that they were Englishman. They were proud of their British heritage and of their King. Benjamin Franklin wrote, “Britain and her Colonies should be considered as one Whole, and not as different States with separate Interests” (pg. 19). This was why Benjamin saw nothing wrong with and even helped his son to acquire the position of the Royal Governorship of New Jersey. The governor was appointed directly by the Crown (not elected by the colonial government). This meant that in order to keep his position, William would find himself having to consistently put the interests of the British government above that of the colonists. The Franklins, however, did not look upon these interests as conflicting. While both Britain and the colonies might have to make some compromises, the end result of their “close relationship” was “mutually beneficial” to both parties (36). As Benjamin and William began to follow very different political careers, however, this belief was continually tested. While his father eventually rejected it, William continued to cling to the traditional and long accepted view of the joint interest of England and its colonies. 4 Stationed in New Jersey, William’s experiences were shaped by direct involvement with colonial governments. At first, he had favorable opinions of the colonies. He grew angry over the “corrupt practices of England’s Board of Trade”, insisting that his “heart remained with the ‘Gentleman of America’” and decrying the British as having “little Knowledge of American affairs.” (37) However, while he found fault with the colonial proprietors, William still continued to cling to the belief that the colonies were dependent on the Crown. They could continue to exist in harmony by looking to the wellbeing of the empire as a whole. The wellbeing of the empire, however, was rooted in law and order. Even though William understood the colonial governments’ arguments against the various taxes that were being levied against them, he also believed that they were grasping for more power than was rightfully theirs. It was acceptable to criticize policy decisions, he argued, but the King and Parliament’s authority must still be respected. His experiences governing the colonies had shown him how “local jealousies” often undermined the public good. (89) Indeed, he and his father had already attempted once to unite the colonies with the Albany Plan of Union. The colonies had rejected it, however, fearing that it was a threat to their individual rights. This rejection, in William’s eyes, sacrificed their stability for idealist notions. 5 Essentially, William feared anarchy. As he observed the revolutionary activities, he wrote in a letter, “All legal Authority and Government seems to be drawing to an End here” (179). William did not support the tyrannous acts of Parliament. Yet he also did not see them as a justification to completely dissolve colonial bonds with England. In his speech to the New Jersey Assembly on January 13, 1775, he warned against the convening of an illegal congress, stating that such an action would destroy “that Form of Government which it is your Duty by all lawful Means to preserve” (176). Clearly, even though William did not share the sentiments of the Patriots, this does not mean that he was necessarily against their ideas of freedom, liberty, and self-government. In the same speech to the New Jersey Assembly, he agreed that the elected members of the assembly were “legal representatives” of the people of New Jersey and that they had been entrusted with “a peculiar Guardianship of their Rights and Privileges.” He disagreed, however, that this self-government could be exercised without the oversight of a stronger and well-established British Empire. Independence from the Crown would result in political suicide and any “Rights and Privileges” previously enjoyed would be lost. 6 William (like so many Loyalists) did not know what the outcome of a Revolutionary War would be. He preferred to stand by a time tested system that offered stability over anarchy. The reasoning behind William’s stance proves that he was not an enemy to the colonies. 7 Benjamin Franklin, on the other hand, as a representative of the colonies in England, came to understand firsthand the stubbornness and corruption of those in Parliament. Unlike William, he did not believe that independence would result in anarchy. Instead, he came to see the colonies as a rival power to that of England. He was cautious about revolution and at first advocated reform in the British government. Soon, however, he came to realize this was impossible. While his son urged the colonial assemblies to try to heal their rift with England peaceably, Benjamin Franklin understood how impractical this was. He saw that Britain refused to listen to the petition of the American colonies. Skemp writes that according to those like Benjamin Franklin, “The assemblies in America were England’s, and indeed, the world’s, last hope for the preservation of liberty. Thus it was more important than ever that the colonists be aware of threats to their rights emanating from the ministry or from a corrupt Parliament” (40). 8 In 1775, Benjamin wrote a pamphlet titled “Observations concerning the increase of Mankind” that noted how America’s population was doubling every generation. Skemp observes, “He clearly saw America as an important and unique part of the British system and believed that in time England would need the colonies more than the colonies would need England” (70). After the passage of the Townshend Acts and his appointment by the Massachusetts legislature as its London agent, “he grew more disgusted with government policy, more jaded by his experiences in England, and more contemptuous of those who served the king.” And, yet, Franklin did not criticize the king directly. Indeed, speaking of George III, he observed that he could “scarcely conceive a King of better Dispositions, of more exemplary Virtues, or more truly desirous of promoting the Welfare of his Subjects” (73). However, by 1768 Skemp points out that Benjamin had come to believe that “Americans were bound to the mother country only through their relationship to the king.” 9 By 1773, Franklin began to question whether the king had betrayed the loyalty of the colonies and whether the colonists had ever owed the king absolute obedience. Skemp notes, “When the first settlers came to America, he said, they voluntarily agreed to obey the English sovereign. It went without saying that their descendants had the right to reverse that voluntary decision to obey the king should circumstances warrant it” (106). Benjamin wrote to his son about the Tea Act, “Between you and I, the late Measures have been, I suspect, very much the King’s own.” No longer were threats to American liberty emanating only from Parliament. Now Benjamin believed that they were coming from the king himself. 10 Neither William nor Benjamin made a decision overnight to join the Loyalist or Patriot camps. Rather, their beliefs developed as turbulent political events swirled around them. Ultimately, these decisions cannot be judged as necessarily morally right or wrong. William was just as much a patriot as his father. He loved the colonies and did not advocate a tyrannical government. Indeed, the ideas he clung to were ones previously shared by all colonists. Unfortunately, they had grown outdated and ultimately not viable. They could not survive the growing tensions between an Empire and her colonies. Historical Spotlight Benjamin and William Franklin: Father and Son, Patriot and Loyalist http://historicalspotlight.com/father-and-son-patriot-and-loyalist/