What is a Case Study?

advertisement

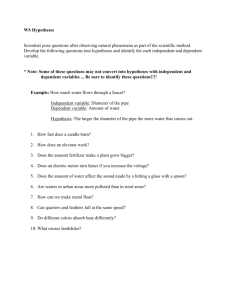

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL REGIONAL POLICY Policy development Evaluation Brussels, November 2009 CASE STUDIES IN THE FRAMEWORK OF EX POST EVALUATION, 2000-2006: EXPECTATIONS AND EXPERIENCES OF THE DG FOR REGIONAL POLICY Veronica Gaffey Head of Evaluation Unit DG for Regional Policy European Commission BACKGROUND Early in 2007 in the Directorate General for Regional Policy we started to think about how we would approach the ex post evaluation of the 2000-2006 programming period of Cohesion Policy. The evaluation presented particular challenges. The Council Regulations governing Cohesion Policy give the European Commission responsibility for the ex post evaluation. But how can we evaluate and draw conclusions across 230 programmes in 25 Member States under Objectives 1 and 2 alone, with a further 150 programmes under the Community Initiatives Urban and Interreg and over 1,000 projects in 17 countries supported by the Cohesion Fund? The programmes demonstrate an enormous diversity in scale and content. For the last programming period, evaluations had been based on national reports with synthesis at EU level. Our analysis and that of the European Court of Auditors was that the approach was not entirely successful. A new approach was needed: We decided to evaluate thematically rather than nationally; and We accepted that not everything would be evaluated, but that we would look more deeply into selected issues and regions in order to understand and build up a picture of the performance of the policy. This created space for case studies as a method to deepen analysis. While we recognise that it is difficult to generalise from a limited number of case studies to the EU as a whole, these case studies generate more "real" evidence of how the policy operates on the ground. However, producing good case studies is challenging and this is a method that has not been used regularly in Cohesion Policy evaluations. For this reason we produced some guidance for our consultants on our expectations from case studies which forms the core D:\533562947.doc Commission européenne, B-1049 Bruxelles / Europese Commissie, B-1049 Brussel - Belgium. Telephone: (32-2) 299 11 11. Office CSM2 A01/244. Telephone: direct line (32-2) 296.95.96. http://ec.europa.eu/comm/regional_policy/ E-mail: veronica.gaffey@ec.europa.eu of this paper. Following a presentation of our expectations, some reflections on the experiences we have had conclude the paper. THE POSITION OF CASE STUDIES WITHIN THE EVALUATION WORK PACKAGES As we designed the terms of reference for the various evaluations, our general approach was the following: To first establish the conceptual basis for the evaluation, drawing on the literature: it is important to reflect on the theoretical foundations for support in a particular area, including market failure and theories of change. This can lead to the generation of hypotheses for testing in the empirical work of the evaluation. To review available administrative data – both financial and physical: although far from perfect, there is an enormous amount of data which can help in the accountability objective of the evaluations – to demonstrate what the Community resources have been spent on. Analysis of this data can also provide insights on patterns of expenditure across different sectors in different contexts and the outcomes achieved. To carry out mostly regional case studies, to deepen analysis. To carry out mini-case studies of good practice focused at the project level to demonstrate what really happens on the ground with Cohesion Policy and highlight practices which might be of interest to other regions. To draw conclusions on the performance of the policy in relation to the theme. Across the ex post evaluation of Objectives 1 and 2, we have 74 case studies either completed or nearly so, with a further 31 under Interreg and Urban. In addition we have 39 good practice mini-case studies. In the ex post evaluation, usually the case studies take place after literature review and analysis of physical and financial data. Their purpose is to deepen analysis and to examine trends and hypotheses derived from earlier analysis in the study in the context of a region or a programme or a member State. We cannot undertake deep analysis of all programmes or regions, so a limited number of case studies across the broad variety of contexts in the EU is usually proposed. Analysis across the case studies should shed light on the trends and hypotheses generated in the literature review, in the examination of macro data and in the review of administrative data on expenditure and indicators and contribute to drawing conclusions and recommendations to be made at a policy level. Often, the case studies may raise additional policy questions which can only be explored in future evaluations. 2 WHAT IS A CASE STUDY? Evalsed gives the following definition of a case study. In-depth study of data1 on a specific case (e.g. a project, beneficiary, town). The case study is a detailed description of a case in its context. It is an appropriate tool for the inductive analysis of impacts and particularly of innovative interventions for which there is no prior explanatory theory. Case study results are usually presented in a narrative form. A series of case studies can be carried out concurrently, in a comparative and potentially cumulative way. A series of case studies may contribute to causal and explanatory analysis What is particular in the DG REGIO case studies is that the focus is usually on a region. They are also concerned with an analysis of impacts rather than with "innovative interventions for which there is no prior explanatory theory". They focus on particular issues or areas of policy intervention in a region rather than on overall developments as such (though it may be necessary to consider overall developments in order to locate the effect of particular types of intervention within these). Having generated theories or hypotheses, based on existing literature and other information, the case studies should test those theories or hypotheses in different contexts. The challenge is to identify the appropriate level of detail and to present it in a way which preserves the "narrative form". In other words, the case study should "tell the story" of the region in relation to the policy theme of the evaluation, though it should do so in an analytical way to bring out the interrelationships between the various aspects which need to be covered. Fundamentally, we are interested in context dependent information in order to learn about how policy is implemented and works in practice in the particular region being examined. Mini case studies in the context of the ex post evaluation focus on a project or a particular approach and analyse its results in context, taking account of success factors and lessons learned. The mini-case studies are added to the Regions for Economic Change part of DG Regional Policy's website. They serve a "visibility" objective by show-casing good practices across the EU. Cross case analysis of innovative projects undertaken for the Commission demonstrates, however, that this approach is another source of potential evidence on the performance of the policy. GATHERING DATA FOR A CASE STUDY It is good practice to design a template for the gathering of information for a case study, especially when the case studies will be carried out by experts in different Member States. For most of DG Regional Policy's evaluations, there is a central core, or coordinating, team with local or national experts. Wherever elements of the template can be completed by central co-ordinating teams from harmonised data available at the EU level, they usually should be so as to ensure some consistency in the starting point of the case study and to avoid potential problems later on when interpreting the results2. The 1 Data should be understood to include qualitative information as well as quantitative statistics. 2 The data used should be comparable across case studies wherever possible, but national or regional data will almost certainly need to be used to supplement and complement comparable EU-level data. In these cases, the main aim should be to ensure that the data used are he most relevant and reliable available and that they are consistent over time if changes between years are being examined. 3 template should also specify the types and broad number of actors to be interviewed. It might also include an interview guide. Whether it does or not, it should emphasise the importance of the local expert seeking explanations and making connections between facts and the views of interviewees about these, as well as verifying that the opinions expressed by interviewees are in line with the facts or can be supported by concrete examples. Most importantly, the local expert must be made fully aware of the central purpose of the case study, of the hypotheses being tested and of the issues which need to be explored as set out in the terms of reference. REPORTING A CASE STUDY – TELLING THE STORY Gathering information through the template is a key step towards completing the case study, but it is by no means the end of the process. The information collected still needs to be turned into a coherent, informative and analytical narrative which links the various details together. This is a challenging task. To accomplish it relies to a large extent on the local expert's knowledge of the region and of the policies followed. This is likely to be important for him or her to be able to organise the information logically and in a way which provides a coherent account of developments in the region and of the role of the particular issues being examined in relation to these. A case study, therefore, is not just a dump of information onto paper. Good case studies should show how the information collected relates to the issues being examined and why it provides evidence for or against a particular hypothesis, as well as drawing attention to the questions which are left open. They should not only describe what happens – or happened over the period in question – but should explain so far as possible the reasons why they happen, or happened, in this way in the region concerned, indicating as far as possible the various factors which contribute, or contributed, to this. Case studies typically relate to complex situations where a wide range of factors and processes interact with each other. Good case studies report both the quantitative and qualitative data available on the situation in a way that makes it possible to understand the situation and the role of the particular aspects being examined within it and, accordingly, enables the expert’s interpretation of events to be meaningfully appraised. The local expert's (often tacit) knowledge of the context, therefore, can be of critical importance for cutting through the (seeming) complexity of the issues being examined and for setting out the evidence coherently and logically so that it can be objectively assessed. Case studies should provide insights into how policy measures as articulated in policy documents actually impact on the ground and how they interact with other policies and developments. In reality, policies can sometimes have perverse effects when put into practice or, alternatively, unexpected synergies when they interact with other measures, both of which can be highlighted by case studies. Through such studies, therefore, we can accumulate new knowledge about the effects of particular policies as well as identifying new ways of achieving particular objectives. Good case studies may also raise questions about the validity of hypotheses and contradict opinions held before they were undertaken, and these ‘negative’ results are as important as more ‘positive’ ones. All those involved in case studies should, therefore, 4 maintain an open mind throughout the process and be prepared to take seriously findings which appear to go against their prior views. It is important to realise that local experts will not necessarily deliver a good case study in the first instance – indeed, it is very unlikely that the initial draft will satisfy all the various criteria mentioned above. It is, therefore, to be expected that there will need to be an interchange between members of the core team who have – or should have – a clear view of the objectives of the study and of what is required from it and the expert in order to clarify particular points and to pose specific questions so as to try to ensure that the study achieves its objectives as best it can. It is also to be expected that the report will need to be edited into good English before it is ready for circulation since few of the experts are likely to be native English speakers and those that are may not necessarily be capable of writing clearly and well. ANALYSING ACROSS CASES Because we usually carry out case studies across a range of different regions (in terms of Objectives, Member States, regional characteristics), comparative analysis of different cases can indicate whether certain findings apply in different contexts or whether they seem specific to particular circumstances. Cross case analysis can enable at least tentative conclusions to be drawn on some of the hypotheses examined in the evaluation. For some hypotheses, it may not be possible to conclude one way or the other and in these cases, the main finding may be that there is a need for further evaluation in the future. For mini-case studies, cross case analysis tends to highlight common problems and success factors across quite different contexts. It should be recognised that it will rarely be possible to generalise across case studies, especially given the relatively small number undertaken, but that this is not the main objective. Discovering a variety of experiences and identifying a range of factors which affect the outcome across case studies will enrich our knowledge about how cohesion policy operates on the ground and is likely to point to ways in which it can be made more effective. SYNTHESIS OF EXPECTATIONS FROM A CASE STUDY In synthesis, we expect from a case study: A coherent analysis in narrative form which explains a complex case: demonstrating how policy is decided in the region, how it is co-ordinated with other policies, how it is implemented, the effects of the policy, and the reasons for those effects. 5 Clear presentation of quantitative data in tables, which combine information from different sources (e.g., data from the regional OP and the sectoral OP presented in the same table) in a synthetic way (all sources to be referenced). Where relevant, a clear map of the region, which marks the towns or sub-regions which are referenced in the text. A synthesis and clear conclusions. A concise text which includes information only if it is relevant to the case. For a mini-case study, we expect a similar approach, although this should be easier as the focus is on one project or approach. EXPERIENCES TO DATE We have been surprised sometimes in the last fewyears how challenging consultants find it to produce good quality case studies which really shed light on the performance of the policy. In the workshop, two consultants will give insights into how they have approached the task. But from our perspective what do we observe? Firstly, we confirm that this is a valuable tool for Cohesion Policy evaluation. We have gained real insights into the performance of the policy and how it functions in different contexts. We will continue to use the method, especially where we are trying to evaluate across the EU and the wide variety of contexts we have under different objectives and in the EU10 and the EU12. We believe that this is an interesting method also for the national and regional level, although we are not aware of any examples of such evaluations in Cohesion Policy at this level. Perhaps we underestimated the time it takes to do a good case study. Even more so, we note in tender documentation that many consultants certainly underestimate the time. A further requirement to do a good case study seems to be in-depth knowledge of the context. Case study authors in general seem to need to be of the nationality of case study context. But we also observe that there is a real added value when the central coordinating team (or I and my colleagues in the Evaluation Unit) read draft case studies and ask questions and challenge findings. Producing good case studies is an iterative process and really benefits from different skills-sets and perspectives to fine-tune the drafts. Narrative is extremely important. Case studies should as the title of our workshop indicates "tell the story". If we want evaluations to make policy makers change policies, they have to be convincing. This requires a skill in presenting and analysing data, identifying what is important and what is not, making links between different elements of information and, crucially, a good drafting style – a skill which is much under-rated these days in evaluation! 6 Select Bibliography European Commission (2008). Analysing ERDF Co-Financed Innovative Projects, Technopolis Group Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings about Case Study Research. Sage Publications Ragin, C. C., & Becker, H. S. (Eds.). (1992). What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Stake, Robert E.(1995). The Art of Case Study Research, Thousand Oaks: Sage. Yin, R. K. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 7