philanthropy-new-millennium

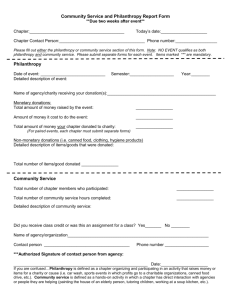

advertisement