Göteborgs universitet Institutionen för kulturvetenskaper FL1200

advertisement

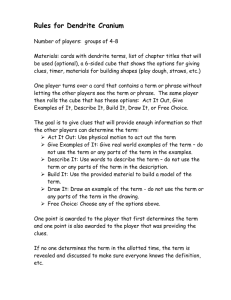

Göteborgs universitet Institutionen för kulturvetenskaper FL1200 Filmvetenskap, fortsättningskurs, 30 hp Delkurs 4: Transmedialt berättande Vårterminen 2012 The Social Spaces Inside and Outside the Game Tine Alavi Examinator: Mats Björkin Index 1. Introduction 1 2. Result 4 3. Analysis 5 4. Summerary 9 5. Sources 9 Abstract As transmedia is changing and challenging conventional media and storytelling the anticipation rises on the wait for future media and media engagements. The Secret Society plays a central role in the mediation of the transmedial project “The Superhero´s”, and presents it self through a questing game that moves with in multiple distinct medias that in turn create the transmedial phenomena through strings of attachments both inside and outside the product in question. This thesis seeks to analyse the social space of the game, hence how spaces of relationships are produced within and outside the game. Other group members: Anton Cornelia Jonas Frida Eric Introduction The Superhero Project The project, The Superhero´s, is built around characters that from an outside perspective think that they have superpowers. From an inside perspective, regarding a creator side, the characters are actors who for the duration of the world construction period of this transmedial project maintain in their respective character identities. The purpose of the project is therefore to create a new world based on a specific group of characters that are in turn embodiments of the superhero phenomenon. The characters: A German mind reader A young invisible boy from Japan A Tyrkish healer Australian woman who has telekinetic powers (moving things with tank engines) Super strong American man Swedish elderly woman from the countryside who talks to animals and plants The characters are presented through the release of their individual histories and engagements in social media platforms; they are given an identity and transformed into “real” people through their accounts. These accounts with in the social media spectrum are released when a documentary of their lives and every day experiences is released. The documentary will carry certain clues that open up for a continuing game of exploration that audiences can engage in. The game is at once constructed around a phenomenon of a secret society, and the discovery of the characters “real” identities. During the whole project audiences, players and others can follow and socialise with the Superhero’s via platforms such as social media, television shows (talk-shows), radio and public appearances. These engagements in turn release more clues that advances and progresses the game. Once the game is solved or revealed a mainstream movie is released which dramatically builds on the characters and their superhero world. Here the mainstream world is opened up and releases a string of publicity and continuing branding, through franchise, television, cyber-games, radio, books, sequels and a final documentary about the whole project. It follows that this project can continue in all eternity if greed endorses it. Note that all of these efforts work through both vertical and horizontal phases. Each distinct media can therefore work both inside and outside the transmedial project. Research Purpose The idea directly and indirectly pushes the boundaries of the objectivity-subjectivity problem as it is constituted between a “fake” and a “real” world. Seeing that the world as we know it is objective and constituted on categorization and boundaries; in this thesis the objectivesubjective problem will be considered a interrelationship that through the course of the project is deconstructed and reinvented again and again. In this sense it becomes clear that the intention of this project is not at firsthand to “foul” its audiences and users but seeks to opens up for both active and interactive practice. Further, the project can be seen in levels across grass-root and mainstream counter poles. This is an interesting experiment as the project from a transmedial perspective can be analysed on more than just the mainstream level. In theory this opens up for an unlimited patch of opportunity that can carry each level further even after they meet. The game is one of the inventions that are, in regards to the level of grass-root and mainstream media, situated in the very intersection. This thesis seeks to explore the social space and the social world of this particular distinct media, the game, with in the transmedial project, The Superhero’s. The goal is to create knowledge of how the game can be understood as a space of relationships with in the social world (reference to Bourdieus theory of social space, see Theory). Theory Prior theory has as according to Dena been rather focused on distinct media and transmedial practices within specific platforms rather than practices with in the transmedial spectrum (Dena, 2009). Here the objective is to explore how Dena´s research purpose, to study the indistinct nature of transmedial practices, can be understood through what Bourdieu calls social space and the social world. Further as Susanna Priest points out qualitative and quantitative media studies borrow much of its theory and methodology from other disciplines (Priest, 2010). Here is an attempt of applying a sociologist perspective. According to Bourdieu people, groups and societies define and categorize a social space through “… principles of differentiation or distribution constituted …” (Bourdieu, 1985, p. 724). Agents are therefore categorized in relations to other spaces (not an actual geographical “place”) and the borders between them, for instance virtual world and physical world (or more extrem, rich and poor). Differentiation and distribution of resources in form of capital (economical, cultural, social and symbolic) and fields (positions of agents in the social world or context) is embodied and objectively constructed as a social space of practices and relationships (and in turn defines situations of power relationships; Bourdieu, 1985, p. 723725). When Bourdieu analyses classes he does not mean a class in a Marxist sense, and not far from an actual group of agents but “ … a set of agents that will present fewer hindrances to efforts at mobilization than any other set of agents” (Bourdieu, 1985, p. 725-726). Agents with in a class, in a specific context (time and position), are more likely, but not always, to have similar practises, interests, and attitudes, with exceptions of course. Nevertheless, these classes that are apart of and are constructors of the social space can be analysed through the positions of agents in an established space of relationships (ibid). Bourdieus theory makes it possible to analyse interactions between agents and positions in the social space through a study of how the space of (social) relationships are established between agents (note that agents is not the equivalence to individuals. Agents can also, in this case be the creators of the transmedial project, or institutions and groups that are affiliated with the project in one way or another). The way in which the analysis will be conducted is through an insight on three different analytical levels that the game can harvest. These levels will be analysed through the study of how the space of (social) relationships between agents are established both through the construction of the social world of the game and the challenges that arise as users of the game become a part of it and reconstruct it through their relationships to it and between each other. Furthermore, ways to understand the games accessibility and representative target groups will be discussed through Bourdieus theory of social spaces. Result The analysis resulted in multiple dimensions of understanding the social space of the game. Presenting the terms capital, field, and habitus the intention was to understand how both the creators and players create meaning throughout the process of transmedial production, and how power and hierarchies in specific contexts can demand certain efforts from either side. These power relationships are to be understood as a part of the social space(s) in the game, and are not to be taken for granted, since transmedia in general is highly dependent on a dynamic relationship between both creator and user. The space of (social) relationships were thus analysed through examples with correspondent theory, which resulted in insight to how creators and players can progress the game, how player to player can form relationships with in the social space, how information can be interpreted, and how these agents can create symbolic meaning and knowledge. Analysis The Interpretative and symbolic: Creators and players The creators successively create a world of symbolic meaning and together with the users interpretation and social communication the game progresses, and is constructed as new symbolic meaning is requested and reproduced. In this scenario I will now call the users, the players, in order to emphasize the symbolic value of the game and its composition that is constructed through interpretive figures. Thus, how the game can be reproduced through the symbolic value that players assert in the game. For instance, the clues make the game proceed, but the value in which the clues carry are dependent on how they are received and how they are interpreted. It is not self-evident that the clues are conspicuously received or valued in the same magnitude that the creators hope for. This makes the spaces of relationships even more important and pushes the creators to understand and create knowledge of the social spaces that the players engage in independent of the physical building stones. In this sense the capital forms are constantly shifted between the creator side and the player side, but also among players as any smaller or bigger shift can throw some capital forms upside down. Note that the capital forms that I am mentioning are economical, cultural, social, and symbolic. According to Bourdieu the social space is on one dimension a result of capital (one the other a result of field and doxa). The capital forms can with strength be transformed into another capital form, which is often the case with economical capital; for instance a transformation to cultural capital (Bourdieu 1986). The game can therefore be seen as a set of social spaces in a social world (the game is in its whole a social world initially constructed by the creators and reproduced by the players). With in the spaces a struggle for position and power is conducted according to capital. The creators in correspondence to the game have control and power over the bigger picture, much like the state. For example, they have the resources and means to change or even “end” (disconnect) the game as they please. On the other side the players (and even audiences and watchers of the game) are at once impregnated with the capital they enter the game with, and capital they get dependently within the game, gained or otherwise struggled for as they move along in the game. For example, social capital gives them opportunity to more or less socialize with in the social networks and social forums that the game enables, or cultural capital on the sublevel of educational capital enables them to understand the terms of the game more or less easily etc. However, as the game has probability to change or reconstruct as new information or new ways to play are presented over time and social spaces the capital invested by a specific player of the game can demand a transformation of capital or/and threaten the “volume” of capital the player beholds, in a sense this is a case for all types of games. Likewise the creators of the game face a similar challenge. The economical capital that they invest in the construction and progress of the game can at any time demand a transformation in to cultural capital, as is the case when the creators are forced to understand the social spaces that the players independently engage in, in order to grasp their demands on the game. Note that symbolic capital is not an actual capital but it can become any given capital form at a given moment in a given context. The creators can release symbolic capital through for instance competitions. In the theory if a player wins a competition with in the game the symbolic capital can present it self as for instance economic capital obtained by the player or vice versa the player invests with economical capital in the competition and loses to its symbolic value. The Construction and Reconstruction: Positions in the Social Spaces The creators implement clues and stories that users can find through social media, radio interviews with the superhero´s, multi-media competitions and other platforms. They preconstruct the social world using multiple platforms in order to broaden the target groups and to target across media with different functions and discourses. As with the Harry Potter world users engage in crosscut conversations about the mysterious Secret Society and the superhero’s. They blogg, chat and push the game by guessing, betting, competing etc. and reconstruct the social world accordingly. By engaging in dialogue with the superhero’s on social media’s (facebook, twitter, websites), users have the opportunity to push the hero´s boundaries and perhaps get clues that take them further in the game. As users move forward they up their position. They also up their position within the social world of the game when they write about it, share clues, and present their guesses etc. The creator’s position is also on the line. As users progress in the social world of the game, the creators are pushed to release new clues, stories, and character experiences, they learn of new dimensions to the game in a constant review of users demands. An example could be to create new characters. This game is not to be confused with a virtual game, it is far from it; the game has every possibility of becoming a quest that reveals “reality” (the made up world) at every given moment (a possible unveiling will however not per say change the game, rather it would make it more of a virtual and practical game, rather than an experimental one, seeing that meaning is created through the relationships between the spaces of the social world). The position of players and creators play an important role in the construction and reconstruction (or rather reproduction) of the game. What Bourdieu calls field! A specific player can in one context of the game be successful and obtain power, while in another context be subject domination and loss. Field is naturally very dependent of capital and can further change the chances of a player to in any given moment during the challenge. For example, a player has come across a clue when watching a television interview with one of the superhero’s. The clue is information revealing an artefact at a museum. The identity of the artefact can be obtained through a puzzle on the superhero’s website that the player has to solve. Once solved the player has to google the artefact in order to decode its meaning etc. All these different contexts can be more or less challenging. The player can if needed start a dialogue on a social network (facebook, blogg etc.) and lead a conversation with other players, and therefore receive help. Nevertheless, the different field therefore determines the opportunity at hand and can be more or less demanding. The position of the player on this dimension is therefore constituted through how power is obtained and maintained within the different fields. Through these different fields spaces of relationships are build, rebuild and deconstructed as players move within the social world of the game. Thus Practices in Play The users seek to solve the mystery of the superhero’s secret society, that is the overall mission. However, what defines the game is rather a social process that guides the participators. In turn these social processes lead to practice. Practise in this sense is a complex phenomena that is, according to Bourdieu, shaped by Habitus (Bourdieu, 1986). Habitus is embodied by agents through structure and society that guide them to act or think in specific ways, and to reproduce patterns. Habitus can change over time and in specific fields and is not a conscious condition but happens unknowingly (Bourdieu, 1977). If we for the sake of analysis take the creators as the structures’ of the game, at least an initial constructor, and the players as agents who are practising with in it and outside it, the practice of the players depend in large of how the creators organise the game, how they convey information, and how they exchange knowledge. Furthermore, each player is influenced by the habitus that constitutes it from the outside. Each player therefore plays accordingly to the embodied habitus that enables it to do things in a certain way. Likewise the creators might be highly influenced in their practices by how the media or transmedial discourse with in the framework of production and ideologies has been or is. For instance, this could be that transmedial productions think of transmedia as a product or a brand that has to be made in to media and more media, with in more platforms and more platforms etc. that are somehow intertwined, instead of seeing transmedia (or any media) as a space of (social) relationships with in a constructed “universe”. Such an approach, with a consideration of all its entailments (field, capital etc.) could help to understand what challenges media and its users, and what could possibly change and perhaps incite new ways of production and new ways of creating meaning and knowledge. Summary The goal was to look at how a particular distinct media with in The Superhero´s project, in this case the game, could be understood as a space of (social) relationships using Bourdieus definition of what a social space is. Here the game shows not to be exclusively a distinct media, and a distinct part in a transmedial project but also a social space were creators and users together define and categorize the boundaries and limitations of their relationship. More or less power and influence over contextual spaces and their content is than seen as a part of the analysis of a transmedial project. The objective here is that regardless of project intention, for instance with in unique platforms or the transmedial practice as a whole, an analysis of the social space and thus relationships, whether conscious or not, creates knowledge of the social world that is constructed (fictively). Sources Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Bourdieu, Pierre. 1885. The Social Space and the Genesis of Groups. In Theory and Society. Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York, Greenwood. Dena, Cristy. 2009. Transmedia Practice: Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World across Distinct Media and Environments: Sidney: University of Sidney Hornig Priest, Susanna. 2010. Doing Media Research, 2 ed. London: SAGE