METHOD - University of Birmingham

advertisement

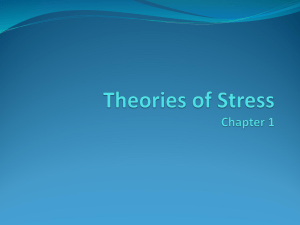

Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study Anna C. Phillips, PhD1, Tessa J. Roseboom, PhD2, Douglas Carroll, PhD1, and Susanne R. de Rooij, PhD2 1 School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Amsterdam Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Address correspondence to: Susanne R. de Rooij, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Amsterdam Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, PO Box 22660, 1100 DD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Tel: **31 20 56 65810; Fax: **31 20 69 12683; E-mail: s.r.derooij@amc.uva.nl Running title: Stress reactivity and adiposity Word count: 6132 Tables: 3 Figures: 2 1 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 The Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study was supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant number 2007B083) and Susanne de Rooij was supported by the European Science Foundation (EUROSTRESS) / Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study Anna C. Phillips, Tessa J. Roseboom, Douglas Carroll, Susanne R. de Rooij 2 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Abstract Objective: Recently, in analyses of data from a large community sample, negative crosssectional and prospective associations between cardiac stress reactivity and obesity were observed. The present study re-examined the association between cardiovascular reactivity and adiposity in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort, with the additional aim of examining the association between cortisol reactivity and adiposity. Methods: Blood pressure, heart rate, and salivary cortisol, were measured at rest and in response to standard laboratory stress tasks in 725 adults. At the same session, height, weight, waist and hip circumference, and skin fold thickness were measured; body mass index and waist-hip ratio were computed. Four to seven years later 460 participants reported current height and weight. Obesity was defined as a body mass index > 30kg/m2. Results: Cross-sectional analyses revealed negative associations between all measures of adiposity and heart rate reactivity; those with a greater body mass index, waist-hip ratio, and skin fold thickness, or categorized as obese displayed smaller cardiac reactions to acute stress. With the exception of waist-hip ratio, the same negative associations emerged for cortisol reactivity. In prospective analyses, low cardiac reactivity was associated with an increased likelihood of becoming or remaining obese in the subsequent 4-7 years. All associations withstood adjustment for a range of possible confounders. Conclusions: The present analyses provide additional support for the hypothesis that it is low not high cardiac and cortisol stress reactivity that is related to adiposity. Key words: adiposity; blood pressure; cortisol; heart rate; obesity; stress reactivity. 1 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 BMI = body mass index, BP = blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, HR = heart rate, SES = socioeconomic status, SBP = systolic blood pressure. INTRODUCTION Longitudinal cohort studies in the United States (1, 2) and elsewhere (3, 4) testify to a striking rise in adiposity, such that obesity has reached epidemic proportions in many Western countries (5). The health consequences are predicted to be dire. Obesity, defined in terms of body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2, has been consistently linked to mortality in general and cardiovascular disease mortality in particular (6-9). Adiposity, a general term for fat deposition, is also associated with a range of cardiovascular and metabolic disease outcomes, such as type 2 diabetes (10, 11) and hypertension (12, 13), as well as overall cardiovascular disease morbidity (14, 15). It has been argued that the location of fat deposition is particularly important for health, specifically abdominal adiposity, measured as waist circumference or waist-hip ratio (16). There is evidence that abdominal fat can predict cardiovascular and metabolic disease outcomes independently of general obesity, as well as providing additional risk information to that afforded by body mass index (12, 17-20). Adiposity, and particularly abdominal adiposity, has also been linked to psychological stress and it has been argued that an increased vulnerability to stress in the abdominally obese may be manifest as physiological hyper-reactivity (21). Through their impact on the neuroendocrine system, stress exposures have been postulated to promote abdominal fat deposition (22). As a corollary, it has been hypothesized that obesity, and especially central adiposity, will be associated with exaggerated cardiovascular reactions to stress (23, 24). Exaggerated cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress have long been considered a risk factor for 2 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 cardiovascular pathology (25) and a number of prospective studies have shown that high reactivity confers a modest additional risk for a range of cardiovascular outcomes, including high blood pressure, carotid atherosclerosis, carotid intima thickness, and increased left ventricular mass (26-32). The question then arises as to whether adiposity and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity are positively related. Evidence for a positive association between adiposity, and especially central adiposity, and exaggerated cardiovascular stress reactivity is mixed and largely based on small studies. In an early study of 20 healthy young men, vascular resistance levels during mental stress were found to be negatively correlated with body mass index but positively associated with waist-hip ratio; no significant associations emerged for blood pressure or cardiac activity during stress (33). In a study of 95 adolescents, the peak systolic blood pressure (SBP) reaction to mental stress was larger for participants in the upper tertile of waist-hip ratio; neither cardiac nor resistance reactions were associated with abdominal adiposity (34). Waist circumference has been reported to be positively associated with heart rate (HR) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) reactivity in a sample of 22 older African American men, although the association with HR reactivity was no longer significant following adjustment for basal blood pressure and the association with DBP reactivity no longer significant following adjustment for basal blood pressure and insulin level (24). In a study of 24 women with body mass indices ≥ 28 kg/m2, those with abdominal obesity, i.e. high waist-hip ratios, had higher DBP and systemic resistance reactions, but lower HR reactions, to a speech task (23). Higher waist circumference has also been associated with higher SBP reactions to four stress tasks in a bi-racial sample of 211 adolescent boys and girls and with higher DBP reactions in the 104 boys; no associations emerged for HR (35). Body mass index 3 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 was not significantly related to cardiovascular reactivity in 225 middle-aged public servants, although waist-hip ratio was positively associated with diastolic reactivity (36). In addition, the upward drift in body mass index and waist-hip ratio over a 3-year follow-up period was not associated with the earlier measures of cardiovascular reactivity. Finally, the change in cardiovascular reactivity following a successful 12-week weight loss intervention did not differ between the intervention and control groups (37). It is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the results of these studies. In most sample sizes were small and, for the most part, poorly representative of the general population. In addition, with one exception (36), the analyses adjusted for few or no possible confounding variables, including baseline cardiovascular levels. Only one study, to date, has examined this issue in a substantial population (38). In the West of Scotland Study, data on cardiovascular reactions to the paced auditory serial addition test and adiposity were available for a community sample 1647 men and women. The most robust and consistent results to emerge from cross-sectional analyses were negative associations between body mass index and waist-hip ratio and HR reactivity. Those with higher body mass indices and waist-hip ratios and those categorized as obese displayed smaller HR reactions to an acute psychological stress task. In prospective analyses, low HR reactivity was associated with an increased likelihood of becoming obese in the following five years. These outcomes are persuasive given the magnitude of the study and the fact that the negative associations between reactivity and adiposity emerged after adjustment for a range of potential confounders, including socio-demographics and medication status. 4 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Although the direction of the observed relationships in the West of Scotland Study ran counter to some, albeit not all, of the findings of other small scale studies, they do fit in a growing body evidence showing that blunted cardiovascular and cortisol stress reactivity is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including depression, poor self-reported health, compromised immunity and addictive behaviour (39, 40). It would appear that depending on the outcomes in question, both low and high stress reactivity can be bad for health conforming to an inverted Ushaped model (39, 41). The opportunity to re-examine the association between cardiovascular reactivity and adiposity was afforded by data collected as part of the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study (42). Reactivity and cross-sectional as well as prospective adiposity data were available for 725 late middle-aged men and women. The richness of the data set allowed adjustment for the same covariates that were controlled for in the West of Scotland analyses. Importantly, not only was cardiovascular stress reactivity measured in the Dutch study but so too was cortisol reactivity. Given that elevated levels of glucocorticoids have been associated with the deposition of abdominal fat (4547), it is perhaps surprising that only a few previous studies have examined cortisol stress reactivity in the context of adiposity in general and abdominal adiposity in particular. In a study of 59 women with high and low waist-hip ratios, those with greater abdominal adiposity had higher cortisol levels during laboratory stress exposure (48). However, in a more recent study comparing the cortisol reactions of 79 abdominally obese and non-obese men and women (49) as well as in a recent study investigating cortisol reactions in 67 female students, there was no association between cortisol reactivity and obesity (50). However, the sample sizes in these studies were invariably small and further study in a larger cohort would seem merited. 5 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 On the basis of increasing evidence showing that blunted cardiovascular and cortisol stress reactivity is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, as well as the West of Scotland Study results showing negative associations between adiposity and cardiac stress reactivity, we hypothesized that cardiovascular and cortisol stress reactivity would be negatively associated with adiposity both cross-sectionally and prospectively in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. METHOD Participants Participants were selected from the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort, which consists of 2414 men and women who were born in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, between November 1943 and February 1947. The selection procedures and subsequent loss to follow up have been described in detail elsewhere (51, 52). Eligibility for participation was based on whether or not cohort members were living in the Netherlands and their address was known to the investigators. In 2002-2004, a study was performed which included an extensive psychological stress protocol. For this study, 1423 eligible cohort members were invited of which 740 visited the clinic. In 2008-2009, a questionnaire was sent to the remaining 1372 eligible cohort members. A total of 460 participants from the 2002-2004 study completed the questionnaire. The studies were approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the adequate understanding and written consent of the participants. The Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study has been designed to investigate the potential consequences of prenatal exposure to famine on health in later life. One can therefore suggest that 6 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 population characteristics may hamper generalization of the present study results. However, this is very unlikely as health differences have mainly been found in the group of people exposed to famine in early gestation which only comprises 8% of the total study sample. Furthermore, in the present study sample, exposed groups did not differ in adiposity measures compared to unexposed groups. General Study Parameters In 2002-2004, a research nurse administered a standardized interview in which information was obtained about socio-economic status (SES), lifestyle, and use of medication. Participants were considered to consume alcohol if they drank at least one alcoholic beverage per week and SES was defined according to the ISEI (International Socio-Economic Index)-92, which is based on the participant’s or their partner’s occupation, whichever has the higher status (53). Values in the ISEI-92 scale ranged from 16 (low status, for example a cleaning person) to 87 (high status, for example a lawyer). Obesity and Adiposity In 2002-2004, height was measured two times in a row for reliability using a fixed or portable stadiometer and weight twice using Seca and portable Tefal scales. Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed from the averages of the two height and weight measurements. Normal weight was defined as BMI < 25, overweight as BMI ≥ 25, but < 30, and obesity as ≥ 30 kg/m2. Waist and hip circumference was measured directly on the body with a flexible tape measure. Waist was measured midway between the costal margin and the iliac crest and hip at the widest point over 7 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 the buttocks to compute the waist-hip ratio. Skin fold thickness was measured three times on two different locations with a skin fold calliper. The first location was above the triceps muscle of the non-dominant arm and the second location was on the same body side directly below the lower angle of the scapula. For both locations, the mean of the three measurements was adopted. In the 2008-2009 questionnaire, participants self-reported current height and weight, and BMI was computed from these self-reported measures. Psychological Stress Protocol The stress protocol started in the afternoon with a baseline period after which three psychological stress tasks were performed, Stroop, mirror tracing task and a speech. The baseline consisted of a 20-min period during which the participant sat in a quiet room. Each stress task lasted 5 minutes with 6 minutes in between and 30 minutes of recovery following the final stress task. The recovery period also consisted of sitting in a quiet room. The Stroop task consisted of a singletrial computerized version of the classical Stroop colour-word conflict challenge (54). After a short introduction, participants were allowed to practise until they fully understood the requirements of the task. Errors and exceeding the response time limit of 5 seconds triggered a short auditory beep. For the mirror-tracing task, a star had to be traced that could only be seen in mirror image (Lafayette Instruments Corp, Lafayette, IN, USA). Every divergence from the line triggered an auditory stimulus. The participants were allowed to practice one circuit of tracing. Participants were instructed to prioritize accuracy over speed and were told that most people could perform 5 circuits of the star without divergence from the line within the given 5 minutes. Prior to the speech task, participants listened to an audio taped instruction in which they were told 8 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 to imagine a situation in which they were falsely accused of pick pocketing (55). They were then given 2 minutes to prepare a 3-minute speech in which they had to respond to the accusation. The speech was videotaped and participants were told that the number of repetitions, eloquence, and persuasiveness of their performance would be marked by a team of communication experts and psychologists. Continuous blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) recordings were made using a Finometer or a Portapres Model-2 (Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Six periods of 5 minutes were designated as the key measurement periods: resting baseline (15 minutes into the baseline period), Stroop, mirror-tracing, speech task (including preparation time), recovery 1 (5 minutes after completing the speech task) and recovery 2 (25 minutes after completing the speech task). A total of seven saliva samples were collected using Salivettes (Sarstedt, Rommelsdorf, Germany): at 5 and 20 minutes of the baseline period, at 6 minutes following completion of the Stroop task and the mirror tracing task, and at 10, 20 and 30 minutes after completion of the speech task. Salivary cortisol concentrations were measured using a time-resolved immunofluorescent assay (DELFIA) (56). The assay had a lower detection limit of 0.4 nmol/l and an inter-assay variance of 9-11% and an intra-assay variance of less than 10%. Perceived stress questionnaires were completed immediately after each of the three stress tasks. The questionnaires consisted of six questions (How relaxed did you feel during performance of the task?; How stressed did you feel during performance of the task?; How difficult did you find the task?; Did you feel committed to the task?; How well did you perform?; How much did you 9 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 feel in control?). The answers were given on a 7-point scale with scores ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Statistical Analyses Resting cortisol was calculated as the mean of the first and the second cortisol concentration measures during the baseline period. Mean systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and HR was calculated for each measuring period by averaging over all blood pressure and heart beat wave forms measured during the 5 minutes of the measuring period. The highest average SBP, DBP, and HR values of the 5 minute measuring periods and the highest of the seven cortisol values were designated as the peak response during the stress protocol. Stress reactivity was defined as the increase from average baseline to these peak values. In addition, we calculated stress reactivity for each stress task (Stroop, mirror, speech) separately by subtracting the baseline value from the average value during each task. A total perceived stress score was derived by adding the scores on the questionnaires performed after each stress task. Correlations between resting physiological activity and peak stress reactivity were tested with Pearson (SBP, DBP and HR) and Spearman (cortisol) correlations. To test whether the stress protocol significantly induced stress responses, we examined the differences between resting physiological activity and peak stress reactivity with T-tests. Associations between peak stress reactivity and potential confounding variables were tested with linear regression. T-tests were applied to test differences between adiposity measures in 2002-2004 and 2008-2009 and logistic and linear regression analyses were applied to test associations between adiposity measures and potential confounding variables. Linear and logistic regression models were applied to analyze 10 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 the associations between obesity and adiposity measures and resting physiological activity, peak stress reactivity and perceived stress measures. Associations between obesity and adiposity measures and resting activity and perceived stress were adjusted for sex, SES, age, alcohol consumption, smoking, and use of anti-hypertensive, anti-depressant and anxiolytic medication. The stress reactivity models were first run without adjustment, then with adjustment for sex, SES, and age and secondly and finally with additional adjustment for alcohol consumption, smoking, use of anti-hypertensive, anti-depressant and anxiolytic medication, and resting physiological activity. Sensitivity analyses were performed by analysing stress reactivity on each of the three stress tasks separately with regression models. Sensitivity analyses were further performed by analysing the differences in peak stress reactivity between three BMI groups (normal weight, overweight, obese) with regression models, which were first run without adjustment and then with full adjustment for the above indicated variables. Prospective associations between adiposity measures and peak stress reactivity were tested with linear regression models in case of BMI change and with logistic regression models in case of obesity change. Models were first run without adjustment and then with full adjustment. Differences in Tables 1 and 2 were tested with T-tests and Mann-Whitney test (for cortisol measures). The variable SES had eight missing values; we imputed these values using the SPSS linear trend at point method. Resting and peak cortisol variables had a skewed distribution and are described with geometric means and standard deviations. These variables were also log-transformed to normality for the regression analyses and the resulting effect sizes are given as percentage differences. Differences were considered to 11 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 be statistically significant if p-values were ≤ .05 (all two-sided). SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used to perform the statistical analyses. RESULTS Study Population Of the 740 cohort members who participated in the 2002-2004 study, 725 completed the psychological stress protocol. Fifteen persons were unable to participate in or finish the stress protocol due to logistical problems (n = 5) or because they were feeling unwell (n = 10). Due to technical problems, BP and HR recordings failed on four individuals. A total of 270 participants had one or more missing cortisol value as results of insufficient saliva. These participants were excluded from the peak reactivity analyses. They did not differ from the group with complete samples with respect to any of the obesity/adiposity measures with the exception of the skinfold measurements (0.29 cm thicker triceps skinfold, p < 0,001 and 0.17 cm thicker subscapular skinfold, p = 0.03). Forty-seven percent (n = 343) of the study population was male; the mean age was 58.3 ± 0.9 years and the mean SES level was 49.7 ± 14.1. A total of 67.6% consumed at least one alcoholic beverage every week; 23.9% were smokers; 23.4% were using anti-hypertensive medication and 12.0% were using anti-depressant or anxiolytic medication. Of the 460 participants who completed the questionnaire in 2008-2009, 47.8% were men; the mean age was 63.8 ± 0.9 years and the mean SES (measured in 2002-2004) was 50.6 ± 13.9. Stress Reactivity The psychological stress protocol significantly perturbed cardiovascular activity and cortisol (all p < .001). Mean peak SBP reactivity was 47.6 ± 20.7 mmHg (mean SBP reactivity during Stroop 12 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 19.6 ± 15.7 mmHg, during mirror 30.2 ± 18.0 mmHg, during speech 46.6 ± 21.7 mmHg), DBP reactivity 21.4 ± 9.1 mmHg (9.2 ± 6.3 mmHg Stroop, 15.8 ± 8.9 mmHg mirror, 20.4 ± 9.7 mmHg speech), HR reactivity 11.8 ± 9.5 bpm (3.9 ± 5.3 bpm Stroop, 4.5 ± 6.2 bpm mirror, 11.3 ± 9.9 bpm speech) and the geometric mean for peak cortisol reactivity was 1.7 ± 3.8 nmol/l (1.0 ± 3.0 nmol/l Stroop, 1.5 ± 4.0 nmol/l mirror, 1.8 ± 4.3 nmol/l speech). Correlations between resting physiological activity and stress reactivity were -0.04 (p = 0.30) for SBP, -0.09 (p = 0.02) for DBP, -0.01 (p = 0.86) for HR and 0.11 (p = 0.02) for cortisol. Men and women did not differ in resting HR or in SBP, DBP and HR stress reactivity, but women had lower resting SBP (-6.8 mmHg, p < .001), resting DBP (-3.4 mmHg, p < 0.001), as well as lower resting cortisol (-24%, p < .001) and cortisol reactivity (-45%, p < .001) compared to men (Table 1). SES (measured continuously) was significantly associated with SBP, HR and cortisol reactivity. Per unit increase in SES, SBP reactivity increased by 0.2 mmHg (p = .01), HR increased by 0.1 bpm (p < 0.001) and cortisol increased by 1% (p = 0.02). Alcohol consumption was negatively associated with HR (-2.2 bpm, p = .004) and cortisol (-27%, p = .02) reactivity; smoking was negatively associated with SBP (-9.7 mmHg, p < .001), DBP (-2.0 mmHg, p = .01), HR (-4.3 bpm, p < .001) and cortisol (-36%, p = .003) reactivity. Use of anti-hypertensive medication was negatively associated with HR reactivity (-1.7 bpm, p = .04) and use of anti-depressant or anxiolytic medication was negatively associated with SBP (-7.4 mmHg, p = .002) and DBP (-2.8 mmHg, p = .01) reactivity. Age was not significantly associated with stress reactivity. Mean perceived stress measures were 11.5 ± 3.8 for relaxedness, 11.1 ± 4.0 for stress, 14.4 ± 3.5 for difficulty, 14.7 ± 4.1 for commitment, 9.2 ± 3.4 for performance, and 10.1 ± 3.6 for control. Obesity and Adiposity 13 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Table 2 shows mean BMI and obesity frequencies in the 2002-2004 and the 2008-2009 study, as well as waist-hip ratio and skin fold thicknesses measured in 2002-2004, according to sex and SES. BMI in 2008-2009 based on self-report data was significantly lower than BMI in 2002-2004 (p < .001). The mean difference was 1.0 ± 2.0 kg/m2. Prevalence of obesity was also lower in the second compared to the first study (-6%, p < .001). Women had a significantly lower waist-hip ratio than men (-0.12, p < .001) as well as higher skin fold thicknesses (1.0 cm, p < .001 for triceps and 0.4 cm, p < .001 sub scapular). Those from a lower SES background (measured continuously) had higher BMI in the first as well as in the second study (0.03 kg/m2 per unit increase in SES, p = .01 and 0.04 kg/m2, p = .01 respectively), a higher waist-hip ratio (0.001 per unit increase in SES, p = .04), a higher skin fold thickness sub scapular (0.01 cm per unit increase in SES, p = 0.05) and were more likely to be obese than those from a higher SES background (OR 1.02 per unit SES, p < .001 in the first study and OR 1.02, p = .03 in the second study). The change in BMI from the first to the second study was not associated with gender or SES. Obesity, Adiposity and Resting Cardiovascular and Cortisol Activity BMI was positively associated with resting SBP, DBP and HR. Per unit increase in BMI, SBP increased by 0.5 mmHg (p = .001), DBP increased by 0.3 mmHg (p = .01) and HR increased by 0.3 bpm (p < .001 (all models fully adjusted). Waist-hip ratio was associated only with resting HR: per unit increase (0.01) in waist-hip ratio, HR increased by 0.2 bpm (p < .001). Triceps skin fold thickness was positively associated with resting HR (0.9 bpm per cm increase, p = .04). Skin fold thickness sub scapular was associated with all resting measures: a positive association was 14 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 found with resting SBP (1.9 mmHg per cm, p = .01), DBP (1.8 mmHg, p < .001) and HR (1.4 bpm, p < .001) and a negative association with resting cortisol (-7%, p = .001). Participants identified as obese in 2002 had significantly higher resting SBP (3.6 mmHg, p = .04), DBP (2.2 mmHg, p = .02) and HR (2.8 bpm, p = .001), but not cortisol. Obesity, Adiposity and Cardiovascular and Cortisol Reactivity: Cross-sectional Analyses Whereas none of the indices of obesity and adiposity was significantly associated with SBP and DBP stress reactivity, all obesity and adiposity measures were significantly negatively associated with HR and cortisol reactivity, with the exception of waist-hip ratio and cortisol reactivity. Effect sizes and other statistics of these associations are given in Table 3. Table 3 also shows that adjustment for sex, SES, and age firstly and then, additionally, for alcohol consumption, smoking, use of anti-hypertensive medication, use of anti-depressant or anxiolytic medication, and resting HR/cortisol, did not attenuate these negative associations with two exceptions: the size of the association between triceps skin fold thickness and cortisol reactivity was halved and no longer statistically significant and the size of the association between sub scapular skin fold and cortisol reactivity became about 30% smaller but was still statistically significant. Participants identified as obese in 2002 also had significantly lower HR (-3.9 bpm, p < .001) and cortisol reactivity (-32%, p = .01), but not lower SBP and DBP reactivity. Adjusting the models for all potential confounders attenuated the associations somewhat (HR reactivity: -3.6 bpm, p < .001; cortisol reactivity: -27%, p = .03). Sensitivity Analyses Stress Reactivity per Stress Task 15 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Analyses on stress reactivity during each of the three stress tasks showed a significant negative association between SBP reactivity and BMI on the Stroop (β = -0.28, t = -2.27, p = .02, R2 = 0.01, fully adjusted model β = -0.25, t = -2.00, p = .05, R2 = 0.07) and mirror task (β = -0.29, t = -2.02, p = .04, R2 = 0.01, fully adjusted model β = -0.34, t = -2.34, p = .02, R2 = 0.06). SBP reactivity was also negatively associated with triceps on the Stroop and mirror task, but these associations did not survive adjustment. DBP reactivity was not significantly associated with any of the obesity and adiposity measures during any stress task. Table 4 shows that HR and cortisol reactivity per stress task showed exactly the same outcomes as in the peak HR and cortisol reactivity analyses (including the fully adjusted analyses, data not shown), with the single exception of an absence of an association between waist hip and HR reactivity on the mirror task. Sensitivity Analyses Obesity Participants were split into three groups to determine whether those with normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) differed in peak HR and cortisol reactivity from those who were overweight but not obese (>25 but < 30 kg/m2), and whether the overweight in turn differed from the obese (>30 kg/m2). Those who were overweight exhibited lower HR stress reactivity than those with normal BMI values (-2.0 bpm, p = .04) and, in turn, those who were obese had lower HR reactivity than those who were overweight (-3.2 bpm, p < .001). This effect is illustrated in Figure 1. Full adjustment for potential confounders changed these associations only marginally (-2.5 bpm, p = .01 and -2.7 bpm, p = .001 respectively). With respect to cortisol reactivity, participants who were overweight did not significantly differ from those with normal BMI, but the obese showed significantly lower 16 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 cortisol stress reactivity than the overweight (30%, p = .02; fully adjusted model 21%, p = .11). This is illustrated in Figure 2. Obesity, Adiposity and Cardiovascular and Cortisol Reactivity: Prospective Analyses Peak blood pressure and cortisol reactivity were not significantly associated with change in BMI between 2002 and 2008. However, lower peak HR reactivity was prospectively associated with an increased likelihood of becoming or staying obese between 2002 and 2008 (OR 1.03, 95%CI 1.01-1.06, p = .01). This association survived adjustment for all potential confounders (OR 1.03, 95%CI 1.00 – 1.05, p = .02). Participants who became or remained obese had a mean HR reactivity of 10.1 ± 8.7 bpm compared to a mean HR reactivity of 12.9 ± 9.7 bpm for those who became or remained non-obese. Obesity, Adiposity and Perceived Stress Participants with higher BMI felt more relaxed during the stress protocol (0.1 point increase per kg/m2 increase in BMI, p = .03, fully adjusted model) and those with a higher waist-hip ratio felt less stressed (-0.1 point decrease per kg/m2 increase in waist-hip ratio, p = .03). Participants who were obese in 2002 scored 0.9 points higher on perceived relaxedness (p = .01). There were no significant associations between any of the other obesity and adiposity measures and perceived stress measures, including the commitment scores. DISCUSSION adapt literature 17 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Higher resting BP levels were associated cross-sectionally with higher BMIs and greater sub scapular skin fold thickness and, in addition, those defined as obese registered relatively high resting BP. Resting HR was positively related to all the indices of adiposity. These outcomes are not without precedent and are reasonably consistent with recent findings on adiposity and resting cardiovascular activity from the West of Scotland Study (38). Numerous other studies also attest that adiposity and obesity are positively related to resting BP (12,13). Further, modestly higher basal HRs in obese versus lean participants has been reported in some, although not all, previous studies (57). The present study extends such associations to skin fold thickness measures. Basal cortisol was not related to adiposity with the exception of a negative association with sub scapular skin fold thickness. The direction of this relationship is surprising given that high cortisol levels have been implicated in abdominal fat deposition (46, 58). However, it should be conceded that the present negative association was manifest at only one site of skin fold measurement and was small in percentage terms. It also emerged in the context of a substantial number of tests of association and, thus, it is not inconceivable that this may be a type 1 error. DBP reactivity was not associated with adiposity. Only one adiposity measure was negatively associated with SBP reactivity, BMI, and only in a task specific manner (during the Stroop and mirror task). In contrast, HR reactivity was associated with all adiposity outcomes; in the crosssectional analyses, participants with lower HR reactivity had greater BMIs, waist-hip ratios, and skin fold thickness, and were more likely to be obese than those with higher HR reactivity. Indeed, as Figure 1 illustrates, there was an orderly negative relationship between BMI category and HR reactivity. The current findings for BP and HR reactivity are seemingly at odds with those from earlier studies (23, 24, 33-36). Although painting a far from consistent picture, these 18 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 earlier studies suggest that adiposity, in particular abdominal adiposity, may be positively related to reactivity, especially for parameters such as DBP that reflect stress-induced changes in systemic vascular resistance. However, with one exception (36), these studies either tested small numbers of participants or samples that were not representative of the general population and hardly, if at all, adjusted for possible confounders. Further, the present results for HR reactivity replicate and extend those recently reported from the West of Scotland Study, the only other analysis of the relationship between reactivity and adiposity in a substantial, population-based, sample (38). In both studies, the robustness of the negative association between HR reactivity and adiposity is demonstrated by its persistence in covariate analysis with adjustment for a large number of potential confounders, including baseline cardiac activity, smoking and alcohol consumption, medication status, age, sex, and SES. In addition, in the West of Scotland Study, HR reactivity predicted which participants were more likely to have become or remain obese over the subsequent five years (38). Precisely the same result emerged from the present analyses. Low cardiac reactivity was associated with an increased likelihood of becoming or remaining obese 47 years later. We might speculate that low HR reactivity may be a risk marker for becoming or remaining obese. However, caution is warranted. Other factors than causal factors may explain the reported association. Moreover, an underlying mechanism linking cardiac reactivity to obesity is yet to be determined. The findings for cortisol stress reactivity, a relatively novel feature of the present study, largely paralleled the cardiac reactivity outcomes. In cross-sectional analyses, cortisol reactivity was significantly negatively associated with all the measures of adiposity except waist-hip ratio. Similar to the association between adiposity and HR reactivity, the relationship between adiposity 19 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 and cortisol reactivity (see Figure 2) appeared to be an orderly one. Previous studies of cortisol reactivity and adiposity are hampered by small samples. Whereas higher cortisol secretion during stress exposure has been reported for women with high as opposed to low waist-hip ratios (48), no differences in cortisol reactivity between abdominally obese and non-obese men and women have also been observed (49, 50). Further, in this latter study, men characterized as ‘reduced obese’, i.e., those who had been obese but who had lost weight, but were still overweight (mean BMI = 28.8 kg/m2), exhibited lower cortisol reactions to the Trier Social Stress Test. The present study findings confirm our hypothesis that cardiovascular and cortisol stress reactivity would be negatively associated with adiposity. However, this seems to mainly hold for HR and cortisol stress reactivity and not so much for BP stress reactivity. Sympathetic nervous system blockade studies indicate that cardiac reactivity in the context of mental stress reflects β-adrenergic activation (54, 55). Indeed, indices of cardiac reactivity seem to be more sensitive than blood pressure reactivity to β-adrenergic blockade (54,55), suggesting, that cardiac reactivity reflects β-adrenergic activation to a greater extent than blood pressure reactivity. This could explain why the present associations mainly obtain for HR reactivity and hardly for blood pressure reactivity. Substantial research has now been directed at the role of the sympathetic nervous system in adiposity and obesity (57). A complex, although still incomplete, story is beginning to emerge. For example, there is reasonably consistent evidence that once individuals have become obese, they are characterized by high basal sympathetic nervous system activity (57). The present baseline cardiovascular data are certainly supportive of this, as are those from the West of Scotland Study (38). In contrast, there is evidence that whereas sympathetic tone may be elevated in obese individuals in the resting state, their sympathetic 20 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 nervous systems may be less responsive to stimulation. For example, there is evidence of a postprandial sympathetic nervous system response, as indicated by higher plasma norepinephrine concentrations and an increased low to high frequency ratio in the HR variability spectrum after ingestion of a meal (58, 59). However, this latter effect was reported to be significantly smaller in obese versus lean individuals (58). In addition, the changes in HR and muscle sympathetic nerve stimulation following infusion of anti-hypertensive and antihypotensive drugs were significantly smaller in the obese than the non-obese (60). The present findings for HR reactivity, then, are what would be expected if a high body mass index, abdominal adiposity, and obesity are associated with generally blunted sympathetic nervous system responses to challenge. It is tempting to process a similar model for the HPA axis, i.e. that obesity and adiposity may be characterized by higher cortisol levels in the resting state but blunted cortisol reactions to challenge, possibly as a result of glucocorticoid receptor down-regulation. For example, Cushing’s syndrome is characterized by chronic hypercortisolemia and many such patients suffer from abdominal obesity (61) and, more importantly, others do report positive associations between basal cortisol levels and adiposity (41,54). Caution is warranted, though, as no positive associations between basal cortisol levels and adiposity emerged in the present study. This may reflect reduced power, although this seems unlikely as the negative cross-sectional associations between adiposity and cortisol stress reactivity were consistent and robust (area under the curve for cortisol was also significantly negatively associated with all adiposity measures, data not shown). Blunted cortisol stress reactivity has also been found to characterize other adverse health and behavioural outcomes such as symptoms of depression (62), poorer self-reported health (63), 21 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 poorer antibody response to vaccination (64), tobacco and alcohol dependence, as well as risk of dependence (65-69), and exercise dependence (70), as has blunted cardiac reactivity (70-73). Mechanistic explanations for our findings can only be speculated upon. The present data fit in a growing body of evidence showing that greater cardiovascular and cortisol stress reactivity may not always be associated with negative health outcomes (39, 40). Blunted stress reactivity may reflect a failing stress response as a consequence of down-regulation of stress receptors. It is possible that HR reactivity in more obese individuals reflect beta-adrenergic receptor downregulation as a result of greater basal sympathetic activity. Alternatively, it has recently been hypothesized that relatively low reactions to acute stress may be a peripheral marker of central motivational dysregulation, i.e. dysfunction of the neural systems that support motivated behaviour (39, 41). The systems in the brain, converging at the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which appear to shape the motivation of our behaviour may be precisely the same circuits that support physiological reactivity. There is some evidence that individuals who show blunted cardiovascular reactions to an acute psychological stress task show blunted neural reactions in the greater amygdale system to the same stress tasks (42). Adiposity / obesity related blunted stress reactivity may fit into this model. In support of this, it was observed in a recent imaging study that the response of the striatum to food intake was negatively associated with body mass index (43). The present study is not without its limitations. First, from observational data it is impossible to determine causality and the direction of causality. The prospective findings, though, reduce the likelihood of reverse causality operating, i.e. adiposity attenuates HR stress reactivity. 22 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Nevertheless, the issue of confounding is ever present in observational studies (74). Although we did adjust statistically for a broad range of potential confounders, residual confounding as a consequence of poorly measured or un-measured variables cannot be wholly discounted. Second, we measured only blood pressure and HR. It could have proved instructive to have a more comprehensive assessment of haemodynamics, allowing us to discern the origins of variations in HR reactivity. Although an increase in afterload as a consequence of vascular reactivity must remain a possibility, it is more likely that heart reactivity with the present stress exposure is, as we infer above, a function of increased sympathetic drive to the heart. Third, 270 participants had one or more missing cortisol samples and were therefore not included in the peak stress reactivity analyses. There were no significant differences in obesity/adiposity measures between those included and those omitted from the cortisol analyses, with the exception of the two skinfold measurements. Given that the results for HR reactivity are consistent across all of the obesity and adiposity measures, we do not believe that null cortisol findings are due to small differences in skinfold measurements between those with one or more missing cortisol values and those with complete cortisol data. However, the attenuation of cortisol reactivity and skinfold measurement associations with full adjustment may reflect that the overall sample had higher skinfold measurements. Finally, BMI at follow-up was based on self-report of height and weight. This is clearly a less reliable estimate of BMI than one based on objectively measured height and weight. Mean BMI was lower in 2008-2009, when it was based on self-report, than in 2002-2004. This could have affected our results if participants with high stress reactivity more often underreported their weight than participants with low stress reactivity. This would seem unlikely, but we cannot exclude it as a possibility. 23 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 This is only the second large scale study to examine the association between adiposity and cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress. High body mass index, waist-hip ratio, and skin fold thickness, as well as conventionally defined obesity were all negatively associated with HR reactivity in cross-sectional analyses; the lower the reactivity, the greater the adiposity. In prospective analyses, low HR reactivity was associated with increased risk of becoming or remaining obese. In addition, this is the first large scale study we know of to consider cortisol stress reactivity in this context. With the exception of waist-hip ratio, the outcomes very much paralleled those that obtained for HR reactivity. Cortisol reactivity was negatively related to adiposity. In conclusion, the present study results confirmed and extended the previous results of the West of Scotland Study that it is low not high cardiac and cortisol stress reactivity that is related to adiposity. References 1. Coakley EH, Rimm EB, Colditz G, Kawachi I, Willett W. Predictors of weight change in men: results from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:89-96. 2. Fine JT, Colditz GA, Coakley EH, Moseley G, Manson JE, Willett WC, Kawachi I. A prospective study of weight change and health-related quality of life in women. JAMA. 1999;282:2136-42. 3. Heitmann BL, Garby L. Patterns of long-term weight changes in overweight developing Danish men and women aged between 30 and 60 years. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:1074-8. 24 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 4. Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Roubenoff R, Evans WJ, Singh MA. Longitudinal changes in body composition in older men and women: role of body weight change and physical activity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:473-81. 5. WHO. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1997. 6. Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, Kipnis V, Mouw T, Ballard-Barbash R, Hollenbeck A, Leitzmann MF. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. New Eng J Med. 2006;355:763-78. 7. Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, Stevens J, VanItallie TB. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282:1530-8. 8. Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW, Jr. Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. New Eng J Med. 1999;341:1097-105. 9. Stevens J, Cai J, Pamuk ER, Williamson DF, Thun MJ, Wood JL. The effect of age on the association between body-mass index and mortality. New Eng J Med. 1998;338:1-7. 10. Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:214-22. 11. Resnick HE, Valsania P, Halter JB, Lin X. Relation of weight gain and weight loss on subsequent diabetes risk in overweight adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:596-602. 12. Hirani V, Zaninotto P, Primatesta P. Generalised and abdominal obesity and risk of diabetes, hypertension and hypertension-diabetes co-morbidity in England. Public Health Nutr. 2007;11:521-7. 25 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 13. Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76-9. 14. Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Boshuizen HC, Woodward M, Knekt P, van Dam RM, Hu FB, Visscher TL, Menotti A, Thorpe RJ, Jr., Jamrozik K, Calling S, Strand BH, Shipley MJ. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1720-8. 15. Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1867-72. 16. Bjorntorp P. The associations between obesity, adipose tissue distribution and disease. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1988;723:121-34. 17. Ardern CI, Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I, Ross R. Discrimination of health risk by combined body mass index and waist circumference. Obes Res. 2003;11:135-42. 18. Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2074-9. 19. Menke A, Muntner P, Wildman RP, Reynolds K, He J. Measures of adiposity and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:785-95. 20. Seidell JC, Cigolini M, Charzewska J, Ellsinger BM, di Biase G. Fat distribution in European women: a comparison of anthropometric measurements in relation to cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:303-8. 26 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 21. Bjorntorp P. Visceral fat accumulation: the missing link between psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease? J Intern Med. 1991;230:195-201. 22. Bjorntorp P. Behavior and metabolic disease. Int J Behav Med. 1996;3:285-302. 23. Davis MC, Twamley EW, Hamilton NA, Swan PD. Body fat distribution and hemodynamic stress responses in premenopausal obese women: a preliminary study. Health Psychol. 1999;18:625-33. 24. Waldstein SR, Burns HO, Toth MJ, Poehlman ET. Cardiovascular reactivity and central adiposity in older African Americans. Health Psychol. 1999;18:221-8. 25. Lovallo WR, Gerin W. Psychophysiological reactivity: mechanisms and pathways to cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:36-45. 26. Allen MT, Matthews KA, Sherman FS. Cardiovascular reactivity to stress and left ventricular mass in youth. Hypertension. 1997;30:782-7. 27. Barnett PA, Spence JD, Manuck SB, Jennings JR. Psychological stress and the progression of carotid artery disease. J Hypertens. 1997;15:49-55. 28. Carroll D, Ring C, Hunt K, Ford G, Macintyre S. Blood pressure reactions to stress and the prediction of future blood pressure: effects of sex, age, and socioeconomic position. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:1058-64. 29. Kamarck TW, Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Manuck SB, Jennings JR, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Exaggerated blood pressure responses during mental stress are associated with enhanced carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged Finnish men: findings from the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Study. Circulation. 1997;96:3842-8. 27 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 30. Lynch JW, Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Does low socioeconomic status potentiate the effects of heightened cardiovascular responses to stress on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis? Am J Pub Health. 1998;88:389-94. 31. Markovitz JH, Raczynski JM, Wallace D, Chettur V, Chesney MA. Cardiovascular reactivity to video game predicts subsequent blood pressure increases in young men: The CARDIA study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:186-91. 32. Treiber FA, Kamarck T, Schneiderman N, Sheffield D, Kapuku G, Taylor T. Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:46-62. 33. Jern S, Bergbrant A, Bjorntorp P, Hansson L. Relation of central hemodynamics to obesity and body fat distribution. Hypertension. 1992;19:520-7. 34. Barnes VA, Treiber FA, Davis H, Kelley TR, Strong WB. Central adiposity and hemodynamic functioning at rest and during stress in adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:1079-83. 35. Goldbacher EM, Matthews KA, Salomon K. Central adiposity is associated with cardiovascular reactivity to stress in adolescents. Health Psychol. 2005;24:375-84. 36. Steptoe A, Wardle J. Cardiovascular stress responsivity, body mass and abdominal adiposity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29:1329-37. 37. Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Effect of a weight-loss program on mental stress-induced cardiovascular responses and recovery. Nutrition. 2007;23:521-8. 38. Carroll D, Phillips AC, Der G. Body mass index, abdominal adiposity, obesity and cardiovascular reactions to psychological stress in a large community sample. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:653-60. 28 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 39. Carroll D, Lovallo WR, Phillips AC. Are large physiological reactions to acute psychological stress always bad for health? Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2009;3:725-43. 40. Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005;30:1010-6. 41. Lovallo WR. Do low levels of stress reactivity signal poor states of health? Biol Psychol 2011;86:121-8. 42. Gianaros PJ, Sheu LK, Matthews KA, Jennings JR, Manuck SB, Hariri AR. Individual differences in stressor-evoked blood pressure reactivity vary with activation, volume, and functional connectivity of the amygdala. J Neurosci 2008;28:990-9. 43. Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science 2008;322:449-52. 44. Roseboom T, de Rooij S, Painter R. The Dutch famine and its long-term consequences for adult health. Early Hum Dev. 2006;82:485-91. 45. Bjorntorp P. Visceral obesity: a "civilization syndrome". Obes Res. 1993;1:206-22. 46. Bjorntorp P, Rossner S, Udden J. "Consolatory eating" is not a myth. Stress-induced increased cortisol levels result in leptin-resistant obesity. Lakartidningen. 2001;98:5458-61. 47. Pasquali R, Vicennati V. Activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in different obesity phenotypes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24 Suppl 2:S47-9. 48. Epel ES, McEwen B, Seeman T, Matthews K, Castellazzo G, Brownell KD, Bell J, Ickovics JR. Stress and body shape: stress-induced cortisol secretion is consistently greater among women with central fat. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:623-32. 29 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 49. Therrien F, Drapeau V, Lalonde J, Lupien SJ, Beaulieu S, Dore J, Tremblay A, Richard D. Cortisol response to the Trier Social Stress Test in obese and reduced obese individuals. Biol Psychol. 2010;84:325-9. 50. 51. Brydon L. Adiposity, leptin and stress reactivity in humans. Biol Psychol 2011;86:114-20 Ravelli AC, van der Meulen JH, Michels RP, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Hales CN, Bleker OP. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet. 1998;351:173-7. 52. Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, Bossuyt PM, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Bleker OP. Adult mortality at age 57 after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:673-6. 53. Bakker B, Sieben I. Maten voor prestige, sociaal-economische status en sociale klasse voor de standaard beroepenclassificatie 1992. Sociale Wetenschappen 1997;40:1-22. 54. Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal interactions. J Ex Psychol. 1935;18:643- 62. 55. Steptoe A, Kearsley N, Walters N. Cardiovascular activity during mental stress following vigorous exercise in sportmen and inactive men. Psychophysiology 1993;30; 245-52. 56. Wood PJ, Kilpatrick K, Barnard G. New direct salivary cortisol and cortisone assays using the "DELFIA" system. J Endocrinol. 1997;155:Supp P71. 57. Fraley MA, Birchem JA, Senkottaiyan N, Alpert MA. Obesity and the electrocardiogram. Obes Rev. 2005;6:275-81. 58. Bjorntorp P, Rosmond R. Obesity and cortisol. Nutrition. 2000;16:924-36. 55. Sherwood A, Allen MT, Obrist PA, Langer AW. Evaluation of beta-adrenergic influences on cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments to physical and psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:89-104. 30 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 56. Winzer A, Ring C, Carroll D, Willemsen G, Drayson M, Kendall M. Secretory immunoglobulin A and cardiovascular reactions to mental arithmetic, cold pressor, and exercise: effects of beta-adrenergic blockade. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:591-601. 57. Tentolouris N, Liatis S, Katsilambros N. Sympathetic system activity in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:129-52. 58. Tentolouris N, Tsigos C, Perea D, Koukou E, Kyriaki D, Kitsou E, Daskas S, Daifotis Z, Makrilakis K, Raptis SA, Katsilambros N. Differential effects of high-fat and high-carbohydrate isoenergetic meals on cardiac autonomic nervous system activity in lean and obese women. Metabolism. 2003;52:1426-32. 59. Welle S, Lilavivat U, Campbell RG. Thermic effect of feeding in man: increased plasma norepinephrine levels following glucose but not protein or fat consumption. Metabolism. 1981;30:953-8. 60. Grassi G, Seravalle G, Cattaneo BM, Bolla GB, Lanfranchi A, Colombo M, Giannattasio C, Brunani A, Cavagnini F, Mancia G. Sympathetic activation in obese normotensive subjects. Hypertension. 1995;25:560-3. 61. Rebuffe-Scrive M, Krotkiewski M, Elfverson J, Bjorntorp P. Muscle and adipose tissue morphology and metabolism in Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1988;67:1122-8. 62. de Rooij SR, Schene AH, Phillips DI, Roseboom TJ. Depression and anxiety: Associations with biological and perceived stress reactivity to a psychological stress protocol in a middle-aged population. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:866-77. 63. de Rooij SR, Roseboom TJ. Further evidence for an association between self-reported health and cardiovascular as well as cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 2010;47:1172-5. 31 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 64. Phillips AC, Carroll D, Burns VE, Drayson M. Neuroticism, cortisol reactivity, and antibody response to vaccination. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:232-8. 65. al'Absi M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to psychological stress and risk for smoking relapse. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;59:218-27. 66. al'Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to psychological stress are associated with early smoking relapse. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:107-17. 67. Lovallo WR, Dickensheets SL, Myers DA, Thomas TL, Nixon SJ. Blunted stress cortisol response in abstinent alcoholic and polysubstance-abusing men. Alcohol, Clin Ex Res. 2000;24:651-8. 68. Panknin TL, Dickensheets SL, Nixon SJ, Lovallo WR. Attenuated heart rate responses to public speaking in individuals with alcohol dependence. Alcohol, Clin Ex Res. 2002;26:841-7. 69. Roy MP, Steptoe A, Kirschbaum C. Association between smoking status and cardiovascular and cortisol stress responsivity in healthy young men. Int J Behav Med. 1994;1:264-83. 70. Heaney JLJ, Ginty AT, Carroll D, Phillips AC. Exercise dependence and cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress: Another case of blunted reactivity? Int J Psychophysiol. 2011;79:323-9. 71. Carroll D, Phillips AC, Hunt K, Der G. Symptoms of depression and cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress: evidence from a population study. Biol Psychol. 2007;75:68-74. 32 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 72. Girdler SS, Jamner LD, Jarvik M, Soles JR, Shapiro D. Smoking status and nicotine administration differentially modify hemodynamic stress reactivity in men and women. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:294-306. 73. Phillips AC, Der G, Hunt K, Carroll D. Haemodynamic reactions to acute psychological stress and smoking status in a large community sample. Int J Psychophysiol. 2009;73:273-8. 74. Christenfeld NJ, Sloan RP, Carroll D, Greenland S. Risk factors, confounding, and the illusion of statistical control. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:868-75. 33 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699-710 TABLE 1. Mean ± SD Values of Cardiovascular and Cortisol Baseline and Reactivity by Sex and Socio-Economic Status SBP (mmHg) DBP (mmHg) HR (bpm) Cortisol (nmol/l) # n Baseline Reactivity Baseline Reactivity Baseline Reactivity Baseline Reactivity Male 343 131.5 ± 19.9 48.1 ± 19.6 67.7 ± 11.1 21.1 ± 8.2 74.0 ± 10.6 11.8 ± 9.1 4.4 ± 1.7 2.3 ± 3.4 Female 382 124.7 ± 1.3* 47.1 ± 21.6 64.3 ± 12.5* 21.6 ± 9.8 74.5 ± 10.5 11.8 ± 10.0 3.3 ± 1.7* 1.3 ± 4.0* Low 345 126.9 ± 21.2 45.2 ± 19.9 65.0 ± 12.3 20.8 ± 9.0 74.1 ± 10.6 10.7 ± 9.1 3.8 ± 1.8 1.6 ± 4.1 High 380 128.9 ± 20.7 49.8 ± 21.1* 66.8 ± 11.6* 21.9 ± 9.1 74.4 ± 10.5 12.8 ± 9.8* 3.8 ± 1.8 1.8 ± 3.6 Sex SES SD = standard deviation; SBP = Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP = Diastolic Blood Pressure; HR = Heart Rate; SES = Socio-Economic Status; * Statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) compared to male / low SES; # Data are given as geometric means ± SD. 34 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699-710 TABLE 2. Obesity and Adiposity Measures by Sex and Socio-Economic Status n BMI (kg/m2) Obesity WH Ratio Triceps (cm) Subscapular (cm) (mean ± SD) (%) (mean ± SD) (mean ± SD) (mean ± SD) 2002 2008 2002 2008 2002 2008 2002 Male 343 220 28.6 ± 4.3 27.6 ± 4.2 29.2 22.7 0.99 ± 0.06 1.61 ± 0.99 2.23 ± 0.91 Female 382 240 28.8 ± 5.1 27.6 ± 5.0 35.9 28.8 0.87 ± 0.07* 2.63 ± 0.86* 2.66 ± 1.11* Low 345 207 29.0 ± 4.8 28.0 ± 4.5 36.8 28.5 0.93 ± 0.09 2.21 ± 1.02 2.50 ± 1.07 High 380 253 28.4 ± 4.7 27.4 ± 4.7 28.9* 23.7 0.92 ± 0.09 2.09 ± 1.08 2.42 ± 1.03 Sex SES BMI = Body Mass Index; SD = standard deviation; WH Ratio = Waist Hip Ratio; SES = Socio-Economic Status; * Statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) compared to male / low SES. 35 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 TABLE 3. Regression Models Obesity and Adiposity Measures and HR and Cortisol peak Reactivity ß t p R2 Crude model -0.39 -5.36 <.001 0.04 Model 1 -0.37 -5.06 <.001 0.05 Model 2 0.38 -5.13 <.001 0.10 Crude model -4% -3.05 .002 0.02 Model 1 -4% -3.28 .001 0.09 Model 2 -4% -3.08 .002 0.11 Crude model -0.15 -3.82 <.001 0.02 Model 1 -0.27 -4.91 <.001 0.05 Model 2 -0.23 -4.05 <.001 0.09 Crude model 1% 1.57 .12 0.01 Model 1 -3% -2.09 .04 0.07 Model 2 -2% -1.54 .12 0.09 -1.00 -2.96 .003 0.01 BMI and HR reactivity BMI and Cortisol reactivity* Waist-Hip Ratio and HR reactivity Waist-Hip Ratio and Cortisol reactivity* Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and HR reactivity Crude model 36 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Model 1 -1.26 -3.24 .001 0.03 Model 2 -1.34 -3.47 .001 0.08 Crude model -21% -3.49 .001 0.03 Model 1 -11% -1.63 .10 0.07 Model 2 -11% -1.66 .10 0.09 Crude model -1.83 -5.42 <.001 0.04 Model 1 -1.84 -5.35 <.001 0.06 Model 2 -1.80 -5.13 <.001 0.10 Crude model -23% -3.73 <.001 0.03 Model 1 -18% -2.96 .003 0.09 Model 2 -16% -2.61 .01 0.11 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and Cortisol reactivity* Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and HR reactivity Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and Cortisol reactivity* BMI = Body Mass Index; HR = Heart Rate; Crude model is the basic unadjusted model; Model 1 includes sex, socio-economic status, and age; Model 2 additionally includes alcohol consumption, smoking, use of anti-hypertensive medication, use of anti-depressant or anxiolytic medication, resting heart rate / cortisol; * ß in percent difference based on log-transformed cortisol reactivity values. 37 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 TABLE 4. Regression Models Obesity and Adiposity Measures and HR and Cortisol Reactivity during each of the Three Stress Tasks. ß t p R2 BMI and HR reactivity -0.24 -5.89 <.001 0.05 BMI and Cortisol reactivity -0.08 -2.73 .01 0.01 Waist-Hip Ratio and HR reactivity -0.07 -2.95 .003 0.01 Waist-Hip Ratio and Cortisol reactivity 0.01 0.64 0.52 0.00 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and HR reactivity -0.83 -4.40 <.001 0.03 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and Cortisol reactivity 0.01 -2.54 .01 0.01 Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and HR reactivity -1.20 -6.37 <.001 0.06 Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and Cortisol reactivity -0.33 -2.68 .01 0.01 BMI and HR reactivity -0.22 -4.50 <.001 0.03 BMI and Cortisol reactivity -0.09 -2.67 .01 0.01 Waist-Hip Ratio and HR reactivity 0.00 -0.06 0.95 0.00 Waist-Hip Ratio and Cortisol reactivity 0.01 0.39 0.69 0.00 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and HR reactivity -1.08 -4.96 <.001 0.03 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and Cortisol reactivity -0.46 -2.93 .004 0.02 Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and HR reactivity -1.36 -6.20 <.001 0.05 Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and Cortisol reactivity -0.44 -2.81 .01 0.01 Stroop Mirror Speech 38 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 BMI and HR reactivity -0.42 -5.42 <.001 0.04 BMI and Cortisol reactivity -0.10 -2.62 .01 0.01 Waist-Hip Ratio and HR reactivity -0.18 -4.25 <.001 0.03 Waist-Hip Ratio and Cortisol reactivity 0.01 0.27 .79 0.00 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and HR reactivity -0.89 -2.48 .01 0.01 Skin Fold Thickness Triceps and Cortisol reactivity -0.50 -2.85 .004 0.01 Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and HR reactivity -1.80 -5.07 <.001 0.04 Skin Fold Thickness sub Scapular and Cortisol reactivity -0.47 -2.62 .01 0.01 BMI = Body Mass Index; HR = Heart Rate; Models are basic unadjusted models. 39 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 Figure Legends Figure 1. Mean values (+ standard error) for heart rate reactivity for participants with a Body Mass Index in the normal range (n = 166), overweight (n = 321) and obese (n = 237); * p < .05. Figure 2. Geometric mean values (+ upper confidence limit) for cortisol stress reactivity for participants with a Body Mass Index in the normal range (n = 109), overweight (n = 210) and obese (n = 135); * p < .05. 40 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 16 14 12 10 8 Heart Rate Reactivity (bpm) 6 4 2 0 normal weight overweight obese 41 Pre-print. Cite as Cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress and adiposity: Cross-sectional and prospective associations in the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Phillips, A., Roseboom, T. J., Carroll, D. & De Rooij, S. R. 2012 In : Psychosomatic Medicine. 74, p. 699710 3 2,5 2 1,5 Cortisol Reactivity (nmol/l) 1 0,5 0 normal weight overweight obese 42