Language attrition

advertisement

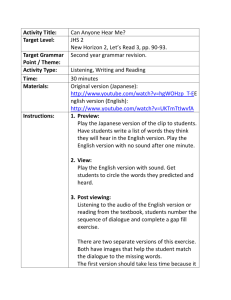

Language attrition Graduation Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Language and Literature Notre Dame Seishin University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Hiromi Ogawa 2004 -1- Contents Check they all match please Page Overview 4 Chapter One 1.1. Introduction 1.2. L1 and L2 Acquisition 1.3. Differences between L1 and L2 A general Introduction Language Attrition 1.5. General Introduction to Attrition 1.6. Focus on the Thesis 4 4 5 1.4. 7 7 8 Chapter Two 2.1. Review Studies on Attrition and Language Retention 10 2.2 Reasons for Language Loss 15 2.3. Features commonly found in Language Attrition 19 2.4. Summary of Chapter Two 23 Chapter Three 3.1. Review of Chapter Two 3.2. The Experiment 3.2.1 Overview 3.2.2. Method 3.2.3. The Subject 3.2.4. Method 3.3. Data 3.3.1. Some interesting points about Table 3.4. Summary Chapter Four 4.1. 4.2. 4.3. 4.4. 4.5. 4.6. Review of Chapter Three Discussion Section The Background Wider Implications for Teachers and Students Advice/Suggestions Conclusion References 23 24 24 24 24 26 28 3 33 35 35 35 36 37 39 40 -2- 32 Overview In this thesis, the author studies the phenomenon that was caused through her experience. The author, who is a Japanese university student, who lived in America for nine months, found that she was gradually losing her mother tongue, Japanese, during her stay in America. She took notes of the incorrect Japanese that she used, and she used those data to make a list showing parallels between her L1, and her L2 English. When doing this she tried to find some rules and causes of this language loss phenomenon. Here she discusses this language loss and seeks some general causes. This phenomenon is now really a general phenomenon that can happen to all of us when we are put into another language context. Moreover, language is such a dynamic entity, that language attrition will always be an interesting and big area to study. If we study abroad, occasionally, we might encounter the phenomenon. It is not only said L2 is English but also other languages. Here, in this thesis, we will look at some knowledge about language attrition from some linguists’ hypothesis and the author’s experiments. In the final chapter, there is some advice for how to avoid language loss, and advance your native language even when you are staying in other country. -3- Chapter One. Introduction to language loss phenomena 1.1 Introduction Many people speak only one native language. have more than one. Some people might What happens to those people who are learning another different language in a different situation? If people around them never speak their native language but their own, they will be forced to speak in their language. Moreover, if you have to stay there for a long time, this situation will cause certain phenomena which have been studied by eminent linguists. or attrition. This phenomenon is called language loss Here, we will study language loss by looking at some theories and an actual experiment. 1.2 L1 and L2 acquisition The terms, L1 and L2, are referred to sometimes in this thesis. These terms need clearly to be defined here. Everyone has their own native language (NL) - the language that a child first learns. This is also known as the primary language, the mother tongue, or the L1 (first language). (Here, we use the common abbreviation L1). In addition, many children learn more than one language from birth and may be said to have more than one mother tongue. For example, if the parents speak only Japanese to the child and they don’t speak to the child in any other language he will speak only Japanese. -4- He acquired Japanese first, therefore this child’s L1 can be said to be Japanese. However, the child whose parents who only speak Japanese but also can speak English may not be said to be the same as the former example. If his parents talk to him in English since he was born, the L1 can be “English.” Any language other than the L1 is called the L2 (second language.) The abbreviation is L2 similar to L1 and this is the common term. Generally, the L2 refers to another language after the L1, regardless of whether it is the second, third, fourth, or fifth language. For instance, a child’s native language is Japanese, and in his life, he acquired English speaking ability. This means that his L1 is Japanese, and the L2 is English. 1.3 Differences between L1 and L2 To distinguish the differences between L1 and L2, some background information will be needed. In the process of the acquiring the L1 and L2 cannot be said to be completely the same. When learning the L1 and L2, the gaps between those will occur. Those gaps are seen in respect of the psycholinguistic mechanisms. Both the L2 and L1 learner reconstruct the language they are learning, it is intuitive to expect that the manner in which they do so will differ. 1 They suggested that the creative construction process between the L1 and L2 acquisition is somewhat different. -5- There are some differences between L1 and L2 acquisition. For example, in the discourse relationship in written texts, the L2 readers had greater overall difficulty with the texts than the L1 readers. However, the parts that both of them feel problematic or easy tend to be the same. Moreover, Chomsky proposed the children’s language acquisition ability as Innate which means that children are biologically programmed for language and that language develops in the child in just the same way that other biological functions develop. Chomsky also called this function, which engages in language development, the language acquisition device (LAD.) His theory is also related to the age-related differences between the L1 and L2 acquisition. Ellis2 points out that however age does not alter the route of acquisition, it has a big effect on the rate and ultimate success. These age-related differences are explained as the “critical period.” Only during this limited period, a particular behavior can be acquired. The optimum age for acquiring another language is in the first ten years of life. After that period, the brain alters its maximum flexibility. From these points on the similarities and differences between the L1 and L2 acquisition, the psycholinguistic mechanisms, discourse acquisition, age-related, and critical period are strongly related. -6- 1.4 A general introduction to the features of Japanese Before describing the features of language attrition, some types of language knowledge need to be introduced. Table 1 explains some potential features which are important for knowing the linguistic systems. This list also plays an important role in analyzing the attrition data will in Chapter Three. Vocabulary Kanji, hiragana, katakana, five vowels Productive Speaking, writing Receptive Listening, Reading Grammar [Subject + Object + Verb ] structure Table 1. 1.5. Japanese basic language features General Introduction to Attrition these first two paras are not really about attrition People have their own native language, but if they go overseas sometimes they can lose some or all of it because they have to speak and work and live in another language. For example, when they just want to exclaim something, they will usually say the words in their own native language. However, when they stay in another country for a long time, they will tend to say the words in that community’s language. For instance, in Japanese, they say “ うわ! ”, but in English “ Wow!” This is an interesting phenomenon, but it will happen -7- with more complicated grammar too. Or, even though they just want to say some simple words, these words can be hard to remember. For example, they will take a lot of time just to say “ごみばこ ” however they can remember it in the other language. Language attrition affects all people. This attrition phenomenon means the loss of the language, not all of it but some parts. This phenomenon has been studied in respect of psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic aspect, linguistic aspects, and theoretical aspects. We also need to discuss the similarities and differences between the L1 and L2 attrition, the reason for why people lose language, and several possible ways to lose language. This we will do in the following chapter. 1.6 Focus of the thesis In Chapter One, we studied type of language knowledge, types of language users about L1 and L2, differences of acquisition between L1 and L2, and some background of language attrition. In Chapter Two, further study of attrition will be discussed considering some eminent linguists’ hypothesis on attrition, and also, the common features found in language attrition like code-switching and TOT phenomenon. In Chapter Three, we will see some examples of language -8- loss through a small case study experiment. The author’s actual experience will be introduced and her language attrition data. The author’s experience is L1 attrition during her stay in Boston for nine months. Those data are put into some categories and explained with the percentages. In Chapter Four’s discussion section we will look at the reasons why language loss happens to us, the background of attrition, and we will look at the wider implications for teachers and students, and present some advice and suggestions for people going overseas. 1 2 Dulay and Burton. 1991, p.113 Ellis. 1993, pp.559-617 -9- Chapter Two Attrition In Chapter One, we looked at general language knowledge and background and looked at attrition in brief. Taking this knowledge the base of the Chapter Two, we will see the further studies on attrition. 2.1. Review studies on attrition and language retention Before we review the similarities and differences between L1 and L2 attrition, we need to review the definitions both of them. The second language attrition is the disintegration or loss of the structure of a language learned after the mother tongue (L1). A person who experiences such loss, a language attriter, is by definition bilingual. As a language is forgotten, it is replaced by another, most often the attriter’s L1, or lost because of disuse. First language attrition is when a person loses his or her mother tongue. For example, in Japanese, there are some common types of attrition such as kanji problems, grammar mixing, word loss, and so on. The kanji problems are referred to incorrect kanji, wrong kanji choice. Grammar happens by mixing up the English grammar system. The Japanese sentence structure is usually written as subject + object + verb, however, once people are faced with attrition, they will use the word order subject + verb + object which is the English way. -10- The word loss is not to remember some words even if those are so simple to say in ordinary life. Many eminent linguists including sociolinguists and psycholinguists have studied language loss for a long time. The most widely used theory for describing the nature of the language loss process was suggested by Jakobson (1941). This hypothesis describes the path of language loss as the opposite of the language acquisition. His theory on language loss has contributed greatly to the work of many linguists. Some terms are used to refer to language attrition and language regression including language loss, and language shift, code-switching and code mixing. We need to look at these definitions carefully. In this thesis, the term language attrition is used because it is generally used widely in linguistics. This is to forget one language as he/she learns another language. Moreover, here we will discuss language attrition with respect to L1 as Japanese, and L2 as English. To discuss the language attrition further, we need to interpret some studies of language attrition. We will look at these later. We should also look at language knowledge (productive skills receptive skills, vocabulary, grammar, etc.), the type of language users (L1, L2), and language attrition. This linguistic knowledge and data will be used to illustrate the survey on language attrition. -11- Language regression is defined the period when a language ceases to be a regular means of communication. 1 A person can experience first language regression when another language comes to replace it as a regular means of communication. This is a process that occurs little by little due to lack of language use. For example, bilinguals make use of the two languages in different contexts. If one of the languages presents more frequency of use, the individual may show some changes in the proficiency of the other language. Also, Hyltenstam and Viberg use the term attrition to refer to a non-temporary regression. It is also mainly caused by a change of environment. There are two types of Language loss. One is the world level area, which is a certain language loses from the world or community historically. The other can be said to be the same phenomenon as language attrition. People lose their L1 through L2 contexts. Code-switching is the use by a speaker of more than one language, dialect, or variety during a conversation. For example, if people want other people to understand their thoughts more correctly, they will choose to use their own language. We also face code-switching phenomena when we say our traditional things that do not apply to any words in other language. Code mixing is the transfer of linguistic elements from one -12- language into another in bilingual speech. Bilinguals sometimes choose their words according to circumstances. If they think it is the appropriate situation to use their one language, they will transfer to the other language. Tip-of-the-tongue is a phenomenon that also often occurs to us and appears as an element in language loss and attrition, and this will be discussed further later on. From all this information about linguistic phenomenon including language attrition, we will now look at some further studies on language attrition. First of all, people lose all or part of their first language in contact situations with a second language. For instance, if person’s L1 is Japanese, and they go to America to study English in an English speaking environment, they will lose some parts of their L1, Japanese. However, there are two types of attrition between losses in the person’s L1, and losses in a second, later-learned language, L2. Here, we are discussing the L1 attrition, and furthermore, taking the information from L2 attrition, we will look at the similarities between L1 and L2 attrition. Give it a number and change the others Some theories of language attrition One of the theories of attrition is the regression hypothesis, which means that “attrition is the mirror image of -13- acquisition” 2 which means the first items lost will be the ones that were acquired last. This is similarly suggested, “Last learned, first forgotten” (Lisa, 2002, Yoshitomi, 1992, P.295). Another similarity is productive skills tend to lead to attrition rather than receptive skills 3 . More of the skills of speaking and writing tend to be lost than the skills of listening and reading. This is because the grammatical rules are more frequent than individual words and may be less likely to be lost because of the frequency role. When we look at the differences between L1 and L2 attrition, the author suggested that the attrition period is different for each other: more we learn language, the less we forget. Generally, the L1 learning period is longer than the L2 learning period and this means that the L1 will remain in our minds more than the L2. Moorcraft & Gardner (1987) commented on this difference in L1 and L1 attrition from the aspect of elements of the language lost. They hypothesized the French students in their study exhibited more grammatical than lexical losses because “most grammatical structures are incompletely and recently learned”4 This was supported by the fact that those students in this study had not mostly learned many of the grammatical structures and they showed attrition after the summer vacation, and many structures that had been learned earlier and more completely than grammatical structures did not show attrition. According to Yoshitomi (1992), when L2 attrition is considered individually, “beginning students lose more grammar than vocabulary, while advanced students lose more vocabulary than grammar” For -14- example, if you have learned English for 6 years and you are an advanced English speaker, while you have learned German for just 3 months, and can merely speak it, you will find some problems when you stop learning both of them. You can speak English remembering the grammatical structure in your mind, but sometimes fail to find the correct words, but you will be in trouble if you are asked to explain personal changes. The reason why the grammatical structure tends not to be forgotten is that grammar is less likely to be lost because of its more “redundant and systematic” nature, its tendency to be more well-connected, and its higher frequency 5 . That is to say, we do not speak thinking of the grammatical problems. enough for us to recall. It is However, words are sometimes needed to be recalled. 2.2 Reasons for Language Loss Why do people lose language? This is the most important topic in this thesis. There are several possible ways to lose language including the lack of use and interference. Lack of use refers to the frequency of using the language is concerned with attrition. When interference occurs the L2 dominates the L1 and takes away some L1 knowledge. Only two possible reasons are discussed here but later there will be further explanation. As we saw, the definition of L1 language attrition is the phenomenon that people lose all or part of their first language when in contact situations with a second language. For example, if your L1 is Japanese and you have a chance to -15- study English intensively for a month, moreover, people are not allowed to use Japanese in that context, your Japanese will become weaker and it may be lost gradually. is easy to see this phenomenon. Sometimes it For example, You may not say correct Japanese words with which you have already been acknowledged, or cannot write the correct kanji letters. For instance, if you just want to say or write some simple words, you cannot remember them and even cannot explain what they are. Below, there are some types of hypothesis why language loss happens. a. lack of use b. interference c. retrieval failure d. schema We will look at each of these below. A. lack of use In Chapter One, we learned about the L1 and L2 learning processes and saw the differences between them. If people learn their L2 during the critical period, their L2 language can be the same level as the L1. However, if they learn it after the critical period, they can never attain the same level as their L1. Once L1 learners stop using a language, they forget some of what they have previously learned, such as letters, idioms, fluency, grammar, and so on, slowly. So, lack of using L1 can lead to forgetting it, but if people use their -16- L2 more than their L1, the L2 can take the role of the L1. This hypothesis also applies to some other potential reasons. B. Interference Interference means that the L2 takes away part of the L1. Interference happens when the target material and other material that was either learned previously interfere with each other. (Example) L1 grammatical structure dominates S 私は 桃を O L2 grammatical structure 私は I 食べる V 食べる eat S 桃を a peach. V O This example means that the English (L2) grammatical structure dominates the Japanese (L1) grammatical structure. Generally, Japanese word order is SOV, while, English is SVO. If the L2 grammatical system interferes with the L1 one, the phenomenon as the latter may occur. Weltens (1989) explained this as people forget a particular thing “A,” because they learned “B” either before (retroactive interference) or after (proactive interference) they learned “A.” of “A” 6 . The memory of “B” interferes with the recall The likelihood and degree of interference becomes greater as the two structures become more similar 7 . This theory would thus predict that the attriting language that is most similar to the corresponding element in the dominant language (L1), is most likely to be interfered with and -17- forgotten. For instance, L2 learning studies that show that more transferring between L1 and L2 occurred when the languages were closely related than when they are not, and when the particular structures in the two languages were similar. 8 C. Retrieval failure This means that people cannot find the L1 information. The information does not disappear but becomes temporarily unavailable. (Example.) 木 – We know this thing but we cannot remember the name of “ 木 ”. We can say this in English as “tree” but not in Japanese. We cannot find the L1’s form (pronunciation - Ki) in our minds. Hansen & Reetz-Kurashige also defined this phenomenon as “the forgotten information is not gone, but has become inaccessible,” and could be obtained with the right cues. 9 This means that the information does not disappear completely, but it exists somewhere in people’s mind. This theory is supported by studies that show that with greater processing time, subjects are able to remember more 10 , and by the existence of the “savings” effect, where relearning forgotten items is more successful than learning similar items for the first item 11 . The difference between interference and retrieval failure is whether people can remember the forgotten items -18- again or not. Interference disturbs the remembering of what they have learned previously, and it is mainly impossible to be retained. Retrieval failure permits people to recall what they want to remember from a prompt. D. Schema Schema is our general knowledge and background that make up all we know. For example, the schema for the wedding ceremony between Japanese and Americans will differ in some ways. Generally in Japan, we can change the wedding dress many times during the ceremony, but not so in America. Brides in America wear the white dress in the ceremony. Thinking more, we will find out the differences between the wedding ceremony style between Japan and America. Those are also because of the differences in schema. We Japanese have learned Japanese well so we can retain a great deal of Japanese information because we have a “schema”, or “structured” system of relationships for Japanese. Our knowledge of this schema allowed us to continue to “generate” correct answers. Schema let us expand our world, but at the same time, schema interferes with remembering what we have learned previously. We sometimes cannot clearly see what the correct way to express what we want to say in our language (L1). 2.3 Features commonly found in language attrition The “permastore” named by Bahrick (1984), means the -19- “response refers to a critical threshold during [or after] learning”, and that once responses reach this threshold, they will not be forgotten (p.33). When people remember an experience, they are not retrieving a particular stored item, but are using their “general knowledge” to construct the memory. For instance, for Japanese people, it is a natural ritual to take off their shoes at home. We do this not because we are forced to, but we know it is the normal way of living in Japan. We store this information in our mind called “permastore.” I moved this to here, it fits better People who encounter language attrition phenomenon often have some simultaneous phenomenon. before, there are TOT and code switching. As introduced Those phenomena are often seen with those people and they recognize it slightly but they cannot be conscious if they have TOT or code switching. Tip-of-the-tongue effect (TOT) TOT is the phenomenon that people have a high feeling of knowing, but cannot recall the answer. Sometimes we encounter such situations as we know the answer, but we cannot exactly say the word. TOT is properly called “The Tip-of-the-Tongue Effect”, which means they feel they know something perfectly, but cannot recall the answer, when we are trying to recall a specific word, and find that it eludes us. Brown and McNeill (1966) attempted to induce a TOT state in their subjects by reading out definitions of comparatively rare words and asking their student subjects to provide the -20- word. If a subject could not say it, but she felt like knowing the word, she was allowed to stop and try to provide as much information as possible about the missing word. They found that the subjects could be accurate in recalling a good deal about the word, even though they could not produce the word itself. names. Another example for this phenomenon is with For instance, if people want to recall the name of the city which has a big mall in Okayama prefecture (Kurashiki), they know it had two letters, first is K and the second is u, but cannot recall other letters. Most readers might have the situation like this. As we can see, TOT can occur in language loss situations. Code-switching Code-switching is defined as the use of more than one language in the course of a single communicative episode. 12 People switch languages while they are talking for many reasons. When they are talking with a friend whose L1 is different from theirs, they will talk by mixing some words that makes the friend understand more clearly. For example, if they just want to describe “hot”, but the friend cannot understand what it means. word as the friend’s L1. code-switching. So, they will use the same meaning That is one example of The reasons for code-switching include adjusting to the environmental situation, lacking the proper words, wanting a better understanding, and lack of knowledge, avoidance/conformation, loss of languages, intention. -21- 1. Adjusting to the environmental situation. This means to adjust to the environment where people are now and show their identity. (e.g.) When people go abroad, they will be put in a situation to have to adjust to and speak the language there. 2. Lacking the proper words The words that do not exist in another language or one that lacks the words for them. (e.g.) kimono – there is no proper words this in another language. 3. For better understanding This means to tell the feelings more properly and correctly. (e.g.) If people want to know how they feel to others, especially emotionally, they will say it in their L1. 4. Lack of knowledge People do not know the words in other languages. (e.g.) When they just do not know what they can say in a certain language, they will use their language. 5. Avoidance/conformation This is to avoid making grammar mistakes. (e.g.) If people are not sure about a word they want to say, they will avoid saying it in their L2, but in their L1. 6. Loss of language -22- This is language attrition itself. (e.g.) People lose the ability of language and vocabulary. 7. Intention This can occur when people intentionally decide to switch codes such as a means to keep secrets, or they just do not want to tell anyone, which means the language take the role of a signal of privacy. (e.g.) If people have a secret with someone, they will have some signal only between them. Those are the functions referred to as code-switching. Perhaps, people have some idea about them. Code switching also has an important role in talking with the people all over the world. Two phenomena were introduced in this section. These might be obstacles for learners, though, they are sometimes useful for living in other countries and we can avoid these phenomenon in advance if we do not want have them. 2.4 Summary of Chapter Two In Chapter Two, we covered language attrition in detail. Moreover, we also see other phenomenon related to language attrition, which are language regression, language loss, language shift, code-switching, code mixing and TOT. Also, some reasons for language loss were introduced and such as lack of use, interference, retrieval failure and schema. They are all the potential reasons for language attrition. -23- We could learn many things about language loss enough to go on to Chapter Three. -24- Chapter Three 3-1. Introduction In Chapter Two, we studied language attrition in some detail. given. Four potential causes of language attrition were Those were lack of practice, interference, retrieval failure, and schema. Moreover, we saw the features commonly found in language loss, TOT and code switching. On the basis of these theories, we will see Chapter Three. Now we will look at an experiment that investigates the types of language loss that occurred in a case study. In this case study, we will see the actual date on language attrition experimented by a student whose L1 is Japanese and L2 is English in other country’s context. 3-2. The Experiment 3.2.1 Overview The Author noticed in her time in the US that was losing some of her Japanese L1. So when the experimenter was faced with the phenomenon of losing some of her L1, she took memos in a notebook. The mistakes in L1 were decided from the experimenter’s perspective and comments of people around her, who spoke the same L1 as her. That perspective was whether it was natural or not, comparing from that of what she had spoken in Japan. This experiment helped her to seek some rules and causes of language attrition. Also, as we studied some phenomenon such as code switching and TOT, she can find out if -25- that phenomenon really happened to her. 3.2.2 Method. In this section we will look at what happens to the subject’s speaking, writing, listening, and reading skills in L1 through the L2 context for nine months by looking at the lists that she made during her stay in Boston. She collected the data by herself and sometimes ask for help with her friends who have the same L1 as her. 3.2.3 The subject The experimenter is a Japanese whose L1 is Japanese. She is also the author of this thesis. years old at that time. She was twenty-one Her major is English linguistics. However, she had time to talk in English not more than 3 or 4 times a week. One time is less than ninety-minutes. course, she spoke Japanese most of time in Japan. Of She could speak, write in, hear, and read Japanese as the same aged people could. She went to Boston in the U.S.A. in September 2002, and was there for 9 months until May 2003. She went to a college in Boston taking the same classes with native Americans. She listened to the lectures, had conversations, and wrote papers in English. She had gradually improved her English skills. She had merely had conversation with Japanese people. She only spoke Japanese less than once a week. She found that language loss happened to her after three months staying in Boston and speaking English in the -26- ordinary life. First, she gradually could not remember Japanese phrases and kanji, and then she often failed to say long sentences in Japanese by making mistakes with the grammar structures. She also could see TOT phenomenon and code-switching frequently. She noticed it when she could not remember “door” in Japanese. In Japanese, it is “戸” , but she could not recall the name. Also, she often gave a faint exclamation in English like “Wow!” when speaking Japanese (code-switching) instead of saying “うわっ!” Those phenomena became a trigger for her to study what happens to her L1 through L2, and she started collect data to seek some rules and causes of language attrition. 3.2.4 Method The experimenter wanted to collect the words or sentences in which she made mistakes. notebook. She collected data in a She took memos when she felt she failed to speak the correct Japanese, could not remember the appropriate Japanese phrases understand the hearing Japanese words quickly, writing Kanji, and so on. The list below is the potential mistakes. Table 1 (in section 1.4) is a list of some potential mistakes in Japanese. Table 2 below is the actual list of mistakes that the subject made in Japanese when she was staying abroad. -27- Make this table fit one page Table 2. Potential Mistakes that she could make in Japanese ProduCtive Speak. Writing RecepTive Listen 1. Code switching 2. Unclear pronunciation 3. Can’t speak with the proper sentences 4. Can’t describe things in details 5. Mistakes on doubled consonant’s expression 6. Mistakes on voiced consonant’s expression 7. Mistakes on the denizens 8. Can’t speak honorific expressions well 9. Incorrect form, strange form 10. Incorrect Kanji 11. Spelling order incorrect 12. The omitted words 13. Inappropriate punctuation mark place 14. Unnatural paragraphing 15. Strange sentence order 16. Can’t remember the people’s names 17. Tends to confirm what people say many times 18. Can’t do dictations 19. Can’t understand honorific expressions Reading 20. Can’t read Kanji 21. Takes a lot of time to read a book 22. Can’t understand summaries easily System Grammar 23. Wrong affirmation and negation 24. Inappropriate conjunctions 25. Not enough sentence elements 26. Unclear distinction among causative voice, passive voice, voluntary, and possibility 27. Improper words choice 28. Wrong verb choice for the body movement 29. Wrong verb choice for food, clothing and shelter 30. Wrong verb choice for hearing and seeing 31. Wrong verb choice for cognition and thinking 32. Wrong verb choice for transference and transition 33. Mixing of intransitive and transitive verb 34. Mistakes on compound verb 35. Unclear distinction between sonkeigo and kenjougo There are the abbreviations for some terms. Productive skills = Produc. Speaking = Speak. Receptive skills = Recep. Listening = Listen. Vocabulary = Vocab. Discourse = Disco. -28- These descriptions on the list above refer to the potential mistakes which the people whose L1 is Japanese might have after long-term usage of English. These features can’t always apply to all people who were once in the English context. We need to analyze these features in consideration of the personal equation. She used this list of categories to collect her data. She collected data for almost five months during her stay in Boston. She took as many memos as possible. However, of course, she could not record all of the mistakes in Japanese. She analyzed the collected data and put them into some categories. She tries to seek the cause of the mistakes, rules, and reasons for the language loss. 3.3 Data The data consisted of 109 Japanese mistakes. Those mistaken Japanese does not mean only words and fraises but also includes grammar and kanji problems. The data are divided into some categories. productive skills, receptive skills and system. of them has other sub-categories. Those are Moreover, each The productive skills are speaking and writing, receptive skills are listening and reading, and system is grammar as was said before. Based on the list B, the experimenter counted the number of categories in which she made mistakes and calculated the percentages for each of them. Table below is the percentage list and some examples. -29- The features in the lists are all based on Table 2. Table 3. The percentages of the Japanese mistakes LEGEND Rank / Number of occurrences / % / Category - Wrong Japanese words - Correct Japanese words - Translated correct English words Rank 1 Number 41 37.6% Code switching - お金がコスト - お金がかかる - costs money Rank 2 Number 13 11.9% Improper words choice - とらねこ - ドラヤキ - Dorayaki Rank 3 Number 11 10.1% Incorrect Kanji - 雑氏 - 雑紙 - Magazines Rank 4 Number 7 6.4% Can’t speak with the proper sentences - 食べてね、夕食を、疲れて寝た、自分の部屋で。 - 夕食を食べてから疲れて自分の部屋で寝た。 - I was tired and fell asleep in my room after eating dinner. Rank 5 Number 6 5.5% Tends to confirm what people say -30- many times - 横になる?(could not understand) - 気分の悪くなった方は横になって下さい。 - Please lay down if you feel bad Rank 5 Number 6 5.5% Unclear distinction between sonkeigo and kenjogo - 私はこちらを召し上がります。 - 私はこちらをいただきます。 - I would like to eat this one. Rank 6 Number 4 3.6% Can’t understand honorific expressions - 航空券・・・? - 航空券は再度お電話を頂きそれからの確定となります。 - Confirming an airplane cricket needs a calling again from you. Rank 6 Number 4 3.6% Unclear distinction among causative voice, passive voice, voluntary, and possibility. - パイが焼けられる。 - パイが焼かれる。 - The pie is baked. Rank 7 Number 3 2.7% Can’t speak honorific expressions well - 食べて頂いてください。 - 召し上がってください。 - Please eat it. Rank 8 Number 2 1.8% Wrong verb choice for the body movement -31- - 足がむせる -足がむれる - The feet get sullen. Rank 8 Number 2 1.8% Wrong verb choice for cognition and thinking - 胸が悪い - 気分が悪い - I feel bad. Rank 8 Number 2 1.8% Wrong verb choice for transference and transition -進むの? -出発するの? - Are you leaving? Rank 8 Number 2 1.8% Mistakes on compound verb - 努力に返す - 努力に応える - The efforts are reworded. Rank 9 Number 1 0.9% Can’t describe things in details - wanted to say “みかん” in Japanese, but could not remember. - みかん - Japanese orange Rank 9 Number 1 0.9% The omitted words - 何かもない - 何もかもない There isn’t anything. Rank 9 Number 1 0.9% - 今日まで 色々 Unnatural paragraphing お世話になりました。 -32- (from a letter) - 今日まで色々お世話になりました。 - I appreciate your kindness. (The blanks problem) Rank 9 Number 1 0.9% Strange sentence order - 帰りました、早くに、昨日。 - 昨日早くに帰りました。 - I got home earlier yesterday. Rank 9 Number 1 0.9% Can’t read Kanji - かつじばん? - 掲示板 - billboards Rank 9 Number 1 -私 0.9% 行く Not enough sentence elements 食堂。 - 私は食堂に行く。 - I’m going to the cafeteria. Rank 9 Number 1 0.9% Mixing of intransitive and transitive verb - 火が上昇され - 火が燃え上がり - The fire burns out. Table 3. The actual mistakes in Japanese 3.3.1 Some interesting points about Table 3 In Table 3, I put the thirty-five potential mistakes in Japanese. However, according to the experiment, listed in Table 3, there are twenty-one actual types of L1 mistakes. Moreover, we can see many mistakes happen because of code-switching. Also, the experimenter had many problems with -33- writing the correct kanji form. As the words which were code-switched are comparatively simple words that are easier to say in L2, the implications are related to the code-switching problem. Similarly, Tomiyama researched a Japanese child who had learned English in a naturalistic setting and subsequently returned to Japan, where he had much less exposure to English. She suggests that, “for the more intimate, personal words, the emotional words and interjections, it might have been more appropriate and natural to the child to use his comfortable L1, and using these L1 words also gave the child a break from his L2 performance”. 13 She collected data from the child at various intervals following his return to Japan, and noted that, during the first five months after his return, the child was able to converse entirely in English, without any code-switch to L1 Japanese, and the process was first seen in “emotion-laden utterances, interjections, and conversational-fillers”. So, if we feel easy or comfortable to say those words in L1 or L2, they will use either of them. In the case of the experiments here, the subject felt comfortable to say those expressions. Lack of use is also concerned to attrition. As to say incorrect kanji, the subject had few opportunities to write and read kanji. When we learn something, for example, other language, we need to study to remember letters and grammars. We can think some reasons why those mistakes happened seen in Table 3. However, lack of use seems to be mainly -34- related to language attrition. 3.4 Summary In Chapter Three, we saw the potential mistakes features and the actual mistakes features in Japanese according to data that experimenter made during her stay in America. There are twenty-one actual mistakes out of thirty-five potential mistakes. Also, we can see many mistakes on the features related to code-switching, and kanji forms. Moreover, we find that there is strong relationship to lack of use, which cause language attrition. There is another reason from the perspective of lexical attrition. Very specific nouns are more prone to attrition than general ones. to Israel. Their subjects were Americans who relocated Their L1 was English, but they had had years of reduced exposure to English. They tried to tell a story from pictures that required them to produce very specific nouns, such as “pond” and “gopher”. The subjects were often unable to produce the correct specific noun. Instead, they either used words, such as “body of water,” with more general semantic features, or words, such as “squirrel,” that were in the same general semantic category as the target word, but contained incorrect specific semantic features. 14 1 2 3 Hyltenstam and Viberg, 1993, p.198 Lisa, 2002, Yoshitomi, 1992, pp.293-318 Hansen & Reetz-Kurashige, 1999, pp.3-20 -35- 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Moorcraft & Gardner, 1987, pp.327-340 Neisser 1984, pp.32-35 Lisa, 2002, Weltens, 1989, p.33 Lisa, 2002, Neisser, 1984, pp.32-35 Hansen & Reetx-Kurashige, 1999, pp.3-20 Hansen & Reetx-Kurashige, 1999, p.10 Hansen & Reetz-Kurashige, 1999, pp.3-20 de Bot & Stoessel, 2000,pp.333-353 Monica Heller, 1991, P.1 Tomiyama, 1999, pp.59-79 Olshtain & Barzilay, 1991, pp.139-150 -36- Chapter Four 4.1. Review of Chapter Three We saw data about the potential mistakes and actual mistakes in Japanese which was collected by a student during her stay for five months out of nine months in America. We also saw the interesting points comparing between Table 2 and Table 3. Now, we will have further discussion from now about this in this chapter. 4.2. Discussion Section We have studied some reasons for the language attrition: lack of use, interference, retrieval failure, and lack of schema. Lack of use and practice cause people to forget what they previously learned. Also, interference which is L2 takes away part of the L1 and retrieval failure that means people cannot find the L1 information will be related to lack of use. Moreover, people forget the information from their schema, because that information is old enough not to stand by. These potential reasons seem to relate to lack of use and practice. 4.3. The background We also learned about the L2 learning process in Chapter One. The famous linguist suggests that loss is a mirror image of acquisition. It will be able to be said at least at the point of main process of language attrition. are some other aspects of attrition. -37- However, there We studied the theory: “beginning students lose more grammar than vocabulary, while advanced students lose more vocabulary than grammar,” in Section 2.1. From this we can also say that verbs seem significantly more resistant to attrition. possible explanation for this. There is a Ellis & Beaton noted that one reason nouns are easier to learn than verbs is that they tend to be more imagable. 1 If nouns are better remembered because they are easier to learn, and they are only easier to learn because they are more imaginable, when the imageability factor is controlled, the nouns are no longer easier, and would no longer be more likely to be remembered. Another difference is that it is easy to remember what we forget more quickly than in the learning process. We have a lot of background information in the process of learning, and our schemata broaden during this period. We do not have to take a lot of time to retain the information. These are some notable possible explanations for the differences between the process of acquisition and language attrition. 4.4. Wider implications for teachers and students The school is the place where the teachers teach their knowledge to their students. Moreover, not only students but also teachers need to learn what they have to teach their students. Teachers might be struggling with how to stop this language attrition and how to teach the way to students. Also, students wonder how they should practice to prevent them from forgetting their L1. The teachers and students will stop -38- learning Japanese if they learn another language in other countries, and as we have seen will start forgetting it too. They will not recognize their Japanese skills are getting low because they do not have to learn Japanese. However, they gradually do lose their Japanese skills. What do they need to do is displayed next section. 4.5. Advice / Suggestions There are several important ways for language learners to keep the L1 while in the L2 context. If we remember the time people learned their L1 as a beginner. They needed to learn how to write and read, spell and write sentences, and how to speak and listen. For example, they had to practice kanji spelling and also they had to remember those meanings. When learning something, people have to continue to practise not to forget what they have previously learned. Here is some advice for learners how not to forget their L1 during staying abroad. 1. Read Japanese Read anything written Japanese language: the website, newspaper articles, books, letters, etc. 2. Write Japanese words and sentences Write Japanese words, particularly using kanji letters. sentences are helpful to use a lot of words. into Japanese from English will be good. -39- Long Also translating 3. Speak in Japanese With Japanese friends, talk or chat about any topic. Also, advise each other on their mistakes with words or idioms and so on and write down these mistaken words so you do not do it again. 4. Listen to Japanese Talk with the Japanese friends or listen to radios, music, news on TV, and etc, in Japanese. These are some of the main strategies to prevent language attrition. This should be practiced everyday, but if it is impossible, at least one hour per three days a week will be needed. Teachers and students will be relieved with these strategies, but saying is easy but practicing is really hard. They need to consider these strategies and practice them with strong will. Furthermore, in Chapter Two, we learned that schemata are helpful to remember what we have learned previously. have enormous information in our mind. into the permastore. We Some of them are put So, to keep that information in schema we also need to practice what we have learned. Teachers need to teach with the way that students can broaden their schema. Still, they need to practice and practice what they learned in the class everyday. -40- 4.6. Conclusion In this thesis we learned that language attrition and its background. Learning processes were compared with language attrition process. Some differences can be seen between them in respect of grammar and nouns resistance. Also, there are some reasons for language attrition, which are lack of use, interference, retrieval failure, and schema. Generally, learners need to prevent language attrition, and solve the problems of their lack of use and schema. Even while people stay abroad and have few opportunities to use Japanese, they need to make efforts to practice Japanese in everyday life. 1 Ellis & Beaton 1993, p.559-617 -41- References Bahrick, H.P. (1984a). Semantic memory content in Permastore: Fifty years of memory for Spanish learned in school. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(1), 1-29. Bahrick, H.P. (1984a). Associations and Organization in Cognitive Psychology: A Elsevier Science Publishing Company. Moorcraft, R. & Gardner, R. C. (1987). Linguistic factors in second language loss. Language Learning, 37(3), 327-340 Neisser, U. (1984). Interpreting Harry Bahrick’s discovery: What confers immunity against forgetting? Journal of Experimental psychology: General, 113(1), 32-35 Olshtain, E. & Barzilay, M. (1991). Lexical retrieval difficulties in adult language attrition. In H.W. Seliger & R.M. Vago, First Laguage Attrition (pp.139-150). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. de Bot, K. & Stoessel, S. (1991). Recapitulation, regression, and language loss, First Language attrition (pp.31-52). de Bot, K. & Weltens,B. (1995). Foreign language attrition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 15, 151-164. -42- Ellis, N. & Beaton A. (1993). Psycholinguistic determinants of foreign language vocabulary learning. Language Learning, 43(4), 559-617 Hansen, L. & Reetz-Kurashige, A. (1999). Investigating second language attrition: An introduction. In L. Hansen, Second language Attrition in Japanese Contexts (pp.3-20). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Tomiyama, M. (1999). The first stage of second language attrition: A case study of a Japanese Contexts of a Japanese returnee. In L. Hansen, Second language Attrition in Japanese context (pp.59-79). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Weltens, B. (1989). The attrition of French as a foreign Language. Dordrecht: Foris Publications. Yoshitomi, A. (1992). Towards a model of language attrition: Neurobiological and psychological contributions. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 3(2), 293-318 Yoshitomi,A. (1999). On the loss of English as a second language by Japanese returnee children. In L. Hansen,M Second Language Attrition in Japanese contexts (pp.80-111). Oxford: Oxford University Press -43- -44-